Overcoming the VQE Measurement Problem: A Guide to Precision Quantum Chemistry on NISQ Devices

The Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) is a leading algorithm for finding molecular ground states on near-term quantum computers, with profound implications for drug discovery and materials science.

Overcoming the VQE Measurement Problem: A Guide to Precision Quantum Chemistry on NISQ Devices

Abstract

The Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) is a leading algorithm for finding molecular ground states on near-term quantum computers, with profound implications for drug discovery and materials science. However, its practical application is hindered by the measurement problem—the challenge of obtaining precise energy estimates from noisy quantum hardware. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals, covering the foundational principles of VQE, the core sources of measurement inaccuracy, advanced mitigation techniques like Quantum Detector Tomography and biased random measurements, and robust validation strategies. By synthesizing the latest research, we offer a pathway to achieving chemical precision in molecular energy calculations, a critical step for reliable quantum-accelerated innovation.

VQE and the Quantum Measurement Challenge: Foundations for Researchers

The Variational Principle, a cornerstone of quantum mechanics, provides the foundational framework for the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE). This hybrid quantum-classical algorithm is designed to leverage the capabilities of Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) hardware. This technical guide details the fundamental role of the variational principle in VQE, its operational workflow, and the significant challenges associated with precision measurement on quantum devices. Furthermore, it explores advanced algorithmic variations and error mitigation techniques that are pushing the boundaries of quantum computational chemistry and drug discovery research.

The variational principle is a fundamental theorem in quantum mechanics that provides a powerful method for approximating the ground state energy of a quantum system for which the Schrödinger equation cannot be solved exactly. It states that for any trial wavefunction ( |\psi(\vec{\theta})\rangle ), the expectation value of the Hamiltonian ( \hat{H} ) provides an upper bound to the true ground state energy ( E_0 ):

[ E[\psi(\vec{\theta})] = \frac{\langle \psi(\vec{\theta}) | \hat{H} | \psi(\vec{\theta}) \rangle}{\langle \psi(\vec{\theta}) | \psi(\vec{\theta}) \rangle} \geq E_0 ]

This principle allows researchers to systematically improve their estimate of ( E_0 ) by varying the parameters ( \vec{\theta} ) of the trial wavefunction to minimize the expectation value. The VQE algorithm directly harnesses this concept, using a parameterized quantum circuit (ansatz) to prepare trial states and a classical optimizer to find the parameters that yield the lowest energy estimate [1] [2].

The VQE Framework and Algorithm

The VQE is a hybrid algorithmic framework that strategically partitions a computational problem between quantum and classical processors. The quantum processor's role is to prepare trial states and measure the expectation value of the problem's Hamiltonian, a task that can be intractable for classical computers as system size increases. The classical processor's role is to iteratively update the parameters of the quantum circuit based on measurement results, steering the system toward the ground state.

Core Components of the VQE Algorithm

The VQE algorithm integrates several key components, summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Core Components of the VQE Algorithm

| Component | Description | Role in VQE | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parametrized Ansatz | A quantum circuit ( U(\vec{\theta}) ) applied to an initial state ( | 0\rangle ) to generate a trial state ( | \psi(\vec{\theta})\rangle ). | Encodes the trial wavefunction; its expressibility determines the reachable states. |

| Hamiltonian Measurement | The Hamiltonian ( H ) is decomposed into a linear combination of Pauli terms ( H = \sumi ci P_i ). | The expectation value ( \langle H \rangle = \sumi ci \langle P_i \rangle ) is estimated via quantum measurement. | ||

| Classical Optimizer | A classical algorithm (e.g., COBYLA, SPSA) that updates parameters ( \vec{\theta} ) to minimize ( \langle H \rangle ). | Closes the hybrid loop by using measurement outcomes to guide the search for the ground state. |

The VQE Workflow

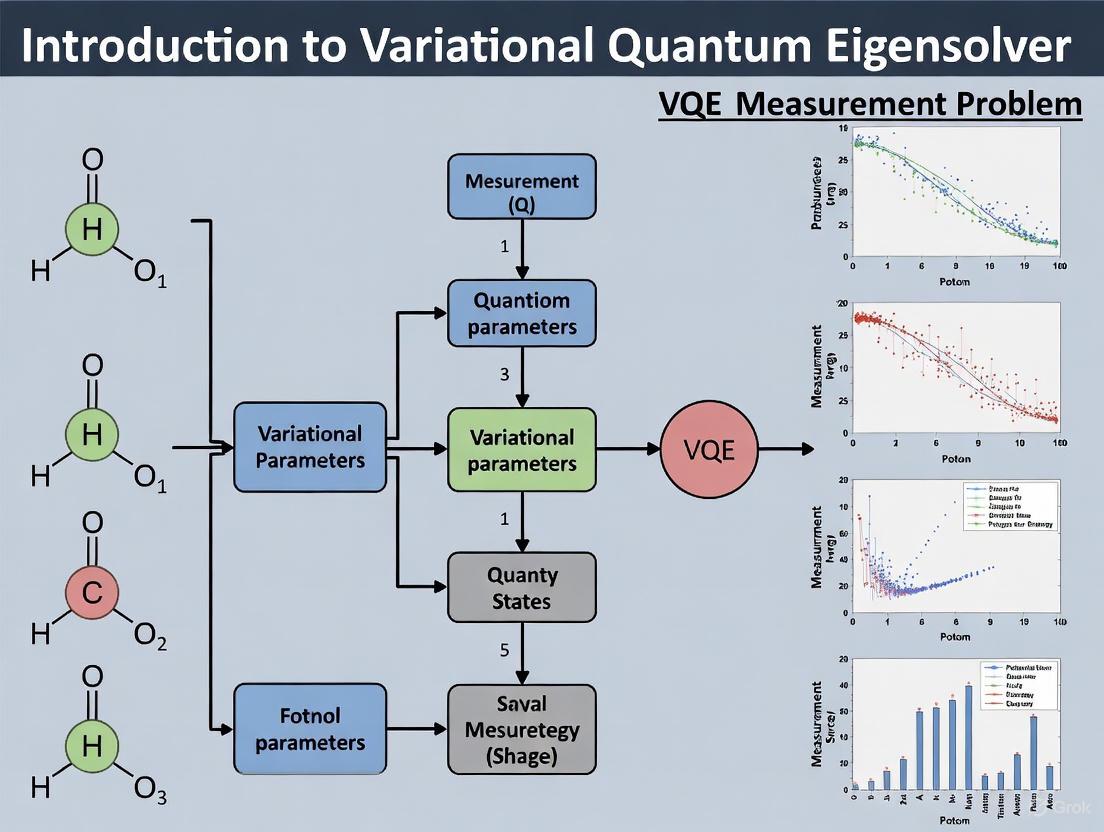

The following diagram illustrates the iterative hybrid loop that constitutes the VQE algorithm.

The Quantum Measurement Challenge in VQE

Accurately measuring the expectation value of the molecular Hamiltonian is the most significant source of overhead and error in the VQE process. The fundamental challenges are twofold: the statistical noise from a finite number of measurement shots ("shot noise") and the inherent physical noise of the quantum device ("readout errors").

Hamiltonian Measurement Overhead

The molecular electronic Hamiltonian in the second-quantized form is mapped to a qubit Hamiltonian, which is a linear combination of Pauli strings (tensor products of Pauli matrices I, X, Y, Z). The number of these terms scales as ( O(N^4) ) with the number of orbitals ( N ), making the measurement process a computational bottleneck [1] [3]. For instance, a single energy evaluation for the BODIPY molecule in a 28-qubit active space requires measuring the expectation values of over 40,000 unique Pauli terms [3].

Advanced Measurement Techniques

To address this challenge, advanced measurement techniques have been developed that go beyond simple term-by-term measurement.

- Informationally Complete (IC) Measurements: This approach involves measuring a fixed set of basis rotations (e.g., all Pauli bases) on the quantum computer. The same data can then be classically post-processed to compute the expectation values of all Pauli terms in the Hamiltonian simultaneously. This is highly efficient for measurement-intensive algorithms [3].

- Locally Biased Random Measurements: A variant of the "classical shadows" technique, this method biases the selection of random measurement bases toward those that are more important for the specific target Hamiltonian. This can significantly reduce the number of shots required to achieve a desired precision [3].

- Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT): This error mitigation technique involves first characterizing the noisy measurement process of the device by building a model of it. This model is then used to post-process the results, creating an unbiased estimator for the true expectation value and reducing the impact of readout errors [3].

Table 2: Advanced Measurement and Mitigation Techniques

| Technique | Principle | Application in VQE |

|---|---|---|

| Pauli Grouping | Groups commuting Pauli terms that can be measured simultaneously. | Reduces the number of distinct quantum circuit executions required. |

| Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT) | Characterizes the device's actual measurement noise to create an error model. | Mitigates systematic readout errors, improving the accuracy of ( \langle P_i \rangle ) [3]. |

| Locally Biased Shadows | Prioritizes measurement settings that have a larger impact on the final energy. | Reduces shot overhead (number of measurements) for complex Hamiltonians [3]. |

| Blended Scheduling | Interleaves circuits for QDT and energy estimation during device runtime. | Averages out time-dependent noise, leading to more homogeneous errors [3]. |

Research Reagents: The Experimental Toolkit

Implementing VQE experiments, whether on real hardware or simulators, requires a suite of software and hardware "research reagents."

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for VQE Experimentation

| Tool/Platform | Type | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Qiskit Nature | Software Library | Provides high-level APIs for quantum chemistry problems, including Hamiltonian generation and ansatz construction [4]. |

| OPX1000 / OPX+ | Control Hardware | Advanced quantum controllers that enable high-fidelity, synchronized control of thousands of qubits with ultra-low latency feedback, essential for dynamic error correction [5]. |

| Dilution Refrigerator | Cryogenic System | Cools superconducting qubits to ~10-20 mK to suppress thermal noise and maintain quantum coherence [6]. |

| QuTiP | Software Library | An open-source Python framework for simulating the dynamics of open quantum systems, used for numerical demonstrations and algorithm development [7]. |

| NVIDIA Grace Hopper | Classical Compute | A high-performance computing architecture integrated with quantum control systems (e.g., DGX Quantum) to accelerate the classical processing in hybrid loops [5]. |

| LY294002 | LY294002, CAS:15447-36-6, MF:C19H17NO3, MW:307.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Cinnabarin | Cinnabarin, CAS:146-90-7, MF:C14H10N2O5, MW:286.24 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Beyond Ground State: Advanced VQE Algorithms

The basic VQE framework has been extended to address a wider range of problems and to improve its performance and resilience.

Algorithmic Extensions

- Variational Quantum Algorithms (VQAs): VQE is a specific instance of the broader VQA class, which applies the same hybrid principle to problems like optimization (QAOA) and machine learning (Variational Quantum Classifier) [2] [4].

- VQE with Quantum Gaussian Filters (QGF): This novel algorithm integrates a non-unitary QGF operator with VQE. The filter selectively damps excited states, accelerating convergence to the ground state. The non-unitary evolution is implemented through a discretized sequence of VQE-optimized steps, showing improved speed and accuracy, especially under noisy conditions [7].

- Problem-Inspired Ansatzes: Moving beyond general "hardware-efficient" ansatzes, problem-specific ansatzes can dramatically improve performance. For example, in financial portfolio optimization, a specifically designed "Dicke state ansatz" can reduce two-qubit gate depth to ( 2n ) and the number of parameters to ( n^2/4 ), making it highly suitable for NISQ devices [8].

The variational principle provides the rigorous quantum-mechanical foundation that makes the VQE algorithm possible. By establishing a guaranteed upper bound for the ground state energy, it enables a hybrid optimization loop that is uniquely suited to the constraints of the NISQ era. While the core theory is elegant, the practical execution of VQE is dominated by the challenge of performing high-precision, low-overhead measurements on noisy quantum hardware. Ongoing research focused on innovative measurement strategies, robust error mitigation, and advanced algorithmic variants like VQE-QGF is critical for overcoming these hurdles. The continued co-design of quantum hardware, control systems, and algorithms will be essential for realizing the potential of VQE to deliver quantum advantage in simulating complex molecular systems for drug discovery and materials sciencearyl.

The Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) has emerged as a leading algorithm for the Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) era, designed to solve key scientific problems such as molecular electronic structure determination and complex optimization [9] [10]. As a hybrid quantum-classical algorithm, its power derives from a collaborative feedback loop between quantum and classical processors. The algorithm's core task is to find the ground state energy of a system, a problem central to fields ranging from quantum chemistry to drug development [11] [12].

This guide provides a high-level technical overview of the VQE workflow, with particular emphasis on the significant challenge known as the measurement problem. This challenge encompasses the statistical noise, resource overhead, and optimization difficulties arising from the need to evaluate expectation values on quantum hardware [13] [12]. We will deconstruct the hybrid loop, detail its components, and explore advanced adaptive strategies and measurement-efficient techniques developed to make VQE practical on current hardware.

The Core Hybrid Loop: Components and Workflow

The VQE algorithm operates on the variational principle of quantum mechanics, which states that the expectation value of a system's Hamiltonian ( \hat{H} ) in any state ( |\psi(\vec{\theta})\rangle ) is always greater than or equal to the true ground state energy ( E0 ) [11] [14]: [ \langle \hat{H} \rangle = \langle \psi(\vec{\theta}) | \hat{H} | \psi(\vec{\theta}) \rangle \ge E0 ] The objective is to variationally minimize this expectation value by tuning parameters ( \vec{\theta} ) of a parameterized quantum circuit (the ansatz) that prepares the trial state ( |\psi(\vec{\theta})\rangle ) [14].

Deconstruction of the VQE Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the continuous feedback loop that defines the VQE algorithm.

The VQE loop integrates specific components, each with a distinct function, as outlined in the table below.

Table 1: Core Components of the VQE Algorithm

| Component | Description | Function in the Hybrid Loop | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qubit Hamiltonian | The system's physical Hamiltonian (e.g., molecular electronic structure) mapped to a qubit operator, often a sum of Pauli strings [11]. | Serves as the objective function ( \hat{H} = \sumi ci P_i ) whose expectation value is minimized. | |||

| Parameterized Ansatz | A quantum circuit ( U(\vec{\theta}) ) that generates trial wavefunctions ( | \psi(\vec{\theta})\rangle = U(\vec{\theta}) | \psi_0\rangle ) from an initial state ( | \psi_0\rangle ) [11] [12]. | Encodes the search space for the ground state on the quantum processor. |

| Quantum Measurement | The process of estimating the expectation value ( \langle \hat{H} \rangle ) by measuring individual Pauli terms ( P_i ) on the quantum state [13]. | Provides the cost function value for the classical optimizer. This is the primary source of the measurement problem. | |||

| Classical Optimizer | An algorithm (e.g., SLSQP, COBYLA, SPSA) that processes the energy estimate and computes new parameters ( \vec{\theta} ) [11] [14]. | Drives the search for the minimum energy by updating circuit parameters in the feedback loop. |

The Central Challenge: The Measurement Problem

In a idealized noiseless setting, the expectation value ( \langle \hat{H} \rangle ) could be determined exactly. However, on real quantum hardware, this value must be estimated through a finite number of statistical samples, or "shots." This introduces measurement shot noise, which is a fundamental challenge for VQE's practicality and scalability [13].

Implications of Shot Noise

- Optimization Instability: Noisy energy evaluations can mislead the classical optimizer, causing it to converge to false minima or stagnate prematurely [13] [12].

- Resource Overhead: Achieving a precise energy estimate requires a large number of measurements, which can be prohibitively expensive. The total number of measurements ( N{\text{total}} ) scales as: [ N{\text{total}} = \sum{i=1}^{M} \frac{1}{\epsiloni^2} ] where ( M ) is the number of Pauli terms in the Hamiltonian and ( \epsilon_i ) is the desired precision for the ( i )-th term [9] [13]. This scaling can be a critical bottleneck for quantum advantage.

Advanced Strategies: Adaptive Algorithms and Efficient Measurement

To combat the measurement problem, researchers have developed advanced VQE variants that build more efficient ansätze and reduce quantum resource requirements.

Adaptive VQE Protocols

Algorithms like ADAPT-VQE and Greedy Gradient-free Adaptive VQE (GGA-VQE) construct a system-tailored ansatz dynamically, rather than using a fixed structure [9] [12]. The core adaptive step is illustrated below.

In the ADAPT-VQE algorithm, at each iteration ( m ), a new unitary operator ( \mathscr{U}^(\theta_m) ) is selected from a predefined pool ( \mathbb{U} ) and appended to the current ansatz [12]. The selection criterion is based on the gradient of the energy with respect to the new parameter: [ \mathscr{U}^ = \underset{\mathscr{U} \in \mathbb{U}}{\text{argmax}} \left| \frac{\partial}{\partial \theta} \langle \psi^{(m-1)} | \mathscr{U}(\theta)^\dagger \hat{H} \mathscr{U}(\theta) | \psi^{(m-1)} \rangle \Big |_{\theta=0} \right| ] This greedy approach ensures that each added operator provides the greatest possible energy gain, leading to compact and highly accurate ansätze [9] [12].

Table 2: Resource Comparison of VQE Algorithm Variants

| Algorithm / Ansatz Type | Key Characteristics | CNOT Count (Example) | Measurement Cost | Robustness to Noise |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UCCSD (Fixed) [11] [9] | Chemistry-inspired, high accuracy for molecules. | High (Static) | High | Moderate |

| Hardware-Efficient (Fixed) [11] [8] | Designed for device connectivity, shallow. | Low to Medium | High | Low (Prone to Barren Plateaus [9]) |

| Original ADAPT-VQE [9] [12] | Fermionic pool (e.g., GSD). | High | Very High | Low in practice |

| CEO-ADAPT-VQE* [9] | Uses novel Coupled Exchange Operator pool. | Up to 88% reduction vs. original ADAPT | Up to 99.6% reduction vs. original ADAPT | High (Resource reduction improves feasibility) |

| GGA-VQE [12] | Employs gradient-free, greedy analytic optimization. | Reduced | Reduced | Improved resilience to statistical noise |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Methods

Table 3: Essential Experimental "Reagents" for VQE Implementation

| Item / Technique | Function in the VQE Experiment |

|---|---|

| PySCF Driver [11] | A classical computational chemistry tool used to generate the molecular Hamiltonian and electronic structure properties (e.g., one- and two-electron integrals) for a given molecule. |

| Qubit Mapper (Parity, Jordan-Wigner) [11] | Transforms the fermionic Hamiltonian derived from quantum chemistry into a qubit Hamiltonian composed of Pauli operators. |

| Operator Pool (e.g., CEO Pool [9]) | A pre-defined set of unitary generators (e.g., fermionic excitations, qubit excitations) from which an adaptive algorithm selects to construct its ansatz. The pool's design directly impacts efficiency and convergence. |

| Classical Optimizer (SLSQP, SPSA) [11] [14] | The classical algorithm responsible for adjusting the quantum circuit parameters to minimize the energy. Gradient-based (SLSQP) and gradient-free (SPSA) optimizers are common, with different resilience to noise. |

| Measurement Grouping [15] | A technique that groups commuting Pauli (or other) operators to be measured simultaneously in a single quantum circuit, drastically reducing the total number of circuit executions required. |

| Error Mitigation Techniques [8] | A suite of methods (e.g., readout error mitigation, zero-noise extrapolation) applied to noisy quantum hardware results to improve the accuracy of the estimated expectation values. |

| 2-Fluoroadenosine | 2-Fluoroadenosine|97% Purity|CAS 146-78-1 |

| Aggreceride A | Aggreceride A |

The VQE's hybrid quantum-classical loop represents a foundational algorithmic structure for the NISQ era, framing the challenge of ground state estimation as a collaborative effort between quantum and classical processors. The measurement problem—encompassing shot noise, resource scaling, and optimization instability—is the most significant barrier to its practical application and potential quantum advantage.

However, the field is rapidly advancing. The development of adaptive algorithms like CEO-ADAPT-VQE and GGA-VQE, which build compact, problem-specific ansätze, demonstrates a path toward drastic resource reduction [9] [12]. Concurrently, innovations in measurement grouping [15] and error mitigation are directly attacking the overhead and noise issues. The integration of these sophisticated strategies is crucial for bridging the gap between theoretical promise and practical implementation, ultimately enabling VQE to tackle problems of real-world significance in drug development and materials science.

In the pursuit of quantum utility, particularly within the framework of the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) and other hybrid quantum-classical algorithms, understanding and mitigating measurement noise is a fundamental challenge. The performance of near-term quantum computers is predominantly constrained by various sources of error, with measurement noise representing a critical bottleneck in obtaining accurate results for quantum chemistry simulations, including those relevant to drug development [16]. The "measurement problem" encompasses a hierarchy of noise sources, from fundamental quantum limits such as shot noise to technical implementation issues like readout noise, each contributing to the uncertainty in estimating expectation values of quantum observables.

This technical guide deconstructs the anatomy of this measurement problem, framing it within the context of VQE research for molecular systems such as the stretched water molecule and hydrogen chains studied in quantum chemistry [17]. We examine the theoretical foundations of different noise types, their impact on algorithmic performance, and provide detailed methodologies for their characterization and mitigation, equipping researchers with the tools necessary to advance quantum computational drug discovery.

Shot Noise: The Fundamental Quantum Limit

Shot noise (or projection noise) arises from the inherent statistical uncertainty of quantum measurement. For a quantum system prepared in a state (|\psi\rangle) and measured in the computational basis, each measurement (or "shot") projects the system into an eigenstate of the observable with probability given by the Born rule. The finite number of shots (Ns) used to estimate a probability (p) leads to an inherent variance of (\sigma^2p = p(1-p)/N_s) [17] [18]. This noise source is fundamental and sets the standard quantum limit (SQL) for measurement precision, which can only be surpassed using non-classical states or measurement techniques.

In solid-state spin ensembles, such as nitrogen-vacancy (NV) centers in diamond, achieving projection-noise-limited readout has been a significant challenge, with most experiments being limited by photon shot noise [18]. Recent advances have demonstrated projection noise-limited readout in mesoscopic NV ensembles through repetitive nuclear-assisted measurements and operation at high magnetic fields ((B_0 = 2.7\ \text{T})), achieving a noise reduction of (3.8\ \text{dB}) below the photon shot noise level [18]. This enables direct access to the intrinsic quantum fluctuations of the spin ensemble, opening pathways to quantum-enhanced metrology.

Readout Noise and Technical Limitations

Readout noise encompasses various technical imperfections in the measurement process, including:

- Photon shot noise: The discrete nature of photon detection in optically-addressed qubits (e.g., NV centers, trapped ions).

- Detector inefficiency: Non-ideal quantum efficiency of photodetectors.

- Measurement cross-talk: Spurious correlations introduced during simultaneous multi-qubit readout.

- State preparation and measurement (SPAM) errors: Incorrect initialization or misclassification of quantum states.

Unlike fundamental shot noise, readout noise can be reduced through improved hardware design and calibration. For example, Quantinuum's H-Series trapped-ion processors have demonstrated significant reductions in measurement cross-talk and SPAM errors through component innovations like improved ion-loading mechanisms and voltage broadcasting in trap designs [19].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Quantum Measurement Noise Types

| Noise Type | Physical Origin | Dependence | Fundamental or Technical | Mitigation Approaches |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shot Noise | Quantum statistical fluctuations | (\propto 1/\sqrt{N_s}) | Fundamental | More measurements, squeezed states |

| Photon Shot Noise | Discrete photon counting in fluorescence detection | (\propto 1/\sqrt{N_\gamma}) | Technical | Improved collection efficiency, repetitive readout |

| Readout Noise | Detector inefficiency, electronics noise | Device-dependent | Technical | Hardware improvements, detector calibration |

| Measurement Cross-talk | Signal bleed-between adjacent qubits | (\propto) qubit proximity | Technical | Hardware design (e.g., ion isolation), temporal multiplexing |

Measurement Noise in VQE and Quantum Chemistry Simulations

Impact on Energy Estimation

In the VQE algorithm for electronic structure problems, the molecular energy expectation value (E(\theta) = \langle \psi(\theta)|\hat{H}|\psi(\theta)\rangle) must be estimated through quantum measurements. The Hamiltonian (\hat{H}) is expanded as a sum of Pauli operators: (\hat{H} = \sumi hi \hat{P}i), requiring measurement of each term (\langle \hat{P}i \rangle) [17]. Both shot noise and readout noise contribute to the uncertainty in the energy estimate:

[\sigma^2E = \sumi hi^2 \sigma^2{Pi} + \sum{i\neq j} hi hj \text{Cov}(\hat{P}i, \hat{P}j)]

where (\sigma^2{Pi}) represents the variance in estimating (\langle \hat{P}_i \rangle).

Recent research on a Tensor Network Quantum Eigensolver (TNQE)—a VQE-variant that uses superpositions of matrix product states—has demonstrated "surprisingly high tolerance to shot noise," achieving chemical accuracy for a stretched water molecule and an H₆ cluster with orders of magnitude reduction in quantum resources compared to unitary coupled-cluster (UCCSD) benchmarks [17]. This suggests that ansatz choice significantly affects susceptibility to measurement noise.

Error Mitigation Techniques

Advanced error mitigation techniques specifically target measurement errors:

- Readout Error Mitigation: Constructs a response matrix (R) that characterizes misclassification probabilities, then applies the inverse to correct counts [20] [21].

- Clifford Data Regression (CDR): Uses classically simulable Clifford data to train a error mitigation model [20].

- Zero-Noise Extrapolation (ZNE): Intentionally increases noise to extrapolate back to the zero-noise limit [20].

Recent work on improving learning-based error mitigation demonstrated an order of magnitude improvement in frugality (number of additional quantum calls) while maintaining accuracy, enabling a 10x improvement over unmitigated results with only (2\times10^5) shots [20].

Table 2: Error Mitigation Techniques for Measurement Noise

| Technique | Principle | Resource Overhead | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Readout Error Mitigation | Invert calibrated response matrix | Polynomial in qubit number | Assumes errors are Markovian |

| Clifford Data Regression (CDR) | Learn error model from Clifford circuits | (O(10^3-10^4)) training circuits | Requires classically simulable circuits |

| Zero-Noise Extrapolation (ZNE) | Extrapolate from intentionally noisy measurements | 3-5x circuit evaluations | Requires accurate noise model |

| Symmetry Verification | Post-select results that obey known symmetries | Exponential in number of checks | Discards data, increases shots |

Experimental Protocols for Noise Characterization

Protocol for Readout Noise Calibration

Objective: Characterize the single-qubit and cross-talk readout errors.

Procedure:

- Prepare each computational basis state (|x\rangle) for (x \in {0,1}^n) (for (n) qubits).

- Perform immediate measurement and record the outcome.

- Repeat each preparation-measurement cycle (N \geq 1000) times to gather statistics.

- Construct the response matrix (R) where (R_{ij} = P(\text{measure } i | \text{prepare } j)).

Data Analysis:

- Single-qubit errors: From the (2\times2) sub-matrices of (R).

- Cross-talk errors: From off-diagonal correlations in the full (2^n \times 2^n) matrix.

Quantinuum's H2 processor demonstrated reduced measurement cross-talk through component innovations, validated via cross-talk benchmarking [19].

Protocol for Shot Noise Profiling

Objective: Determine the number of shots required to achieve target precision for a specific observable.

Procedure:

- Select a representative set of quantum states (e.g., Hartree-Fock, coupled-cluster states).

- For each state, measure a target observable (\hat{O}) with varying shot numbers (N_s \in [10^3, 10^6]).

- Compute the statistical variance (\sigma^2O(Ns)) for each (N_s).

- Fit to expected scaling (\sigma^2O = a/Ns) and extract constant (a).

Application: The TNQE algorithm demonstrated reduced shot noise sensitivity, achieving chemical accuracy with fewer shots than UCCSD-type ansatzes [17].

Visualization of Measurement Noise Relationships

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Experimental Resources for Measurement Noise Research

| Resource/Technique | Function in Measurement Research | Example Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity Readout Systems | Minimizes technical readout noise | Quantinuum H2 trapped-ion processor with improved SPAM [19] |

| Repetitive Nuclear-Assisted Readout | Reaches projection noise limit in ensembles | NV center readout at 2.7 T magnetic field [18] |

| Clifford Data Regression (CDR) | Mitigates measurement errors via machine learning | Error mitigation on IBM Toronto [20] |

| Multi-Level Quantum Noise Spectroscopy | Characterizes noise spectra across qubit levels | Transmon qubit spectroscopy of flux and photon noise [22] |

| Mirror Benchmarking | System-level characterization of gate and measurement errors | Quantinuum H2 validation [19] |

| Tensor Network Ansätze | Reduces shot noise sensitivity in VQE | TNQE for H₂O and H₆ molecules [17] |

| Tetraphenylstibonium bromide | Tetraphenylstibonium Bromide|510.1 g/mol|CAS 16894-69-2 | Tetraphenylstibonium Bromide is an organoantimony reagent for research. It is a pentavalent stibonium salt. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Colistin | Colistin | Colistin is a last-resort antibiotic for researching multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO). |

The anatomy of the measurement problem in quantum computing reveals a complex hierarchy from fundamental shot noise to addressable technical readout errors. For VQE applications in drug development, where precise energy estimation is crucial, understanding and mitigating these noise sources is essential. Recent advances in hardware design, such as Quantinuum's H2 processor with reduced measurement cross-talk, combined with algorithmic innovations like the shot-noise-resilient TNQE and efficient error mitigation techniques like improved CDR, provide a multi-faceted approach to overcoming these challenges. As the field progresses toward quantum utility, continued refinement of measurement techniques and noise characterization protocols will play a pivotal role in enabling accurate quantum computational chemistry and drug discovery.

The Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) has emerged as a leading algorithm for quantum chemistry simulations on noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices, offering a promising path toward calculating molecular ground-state energies where classical methods struggle [23] [24]. The algorithm operates on a hybrid quantum-classical principle: a parameterized quantum circuit (ansatz) prepares trial states, and a classical optimizer adjusts these parameters to minimize the energy expectation value of the molecular Hamiltonian [23]. Achieving chemical accuracy—an energy precision of 1.6 × 10â»Â³ Hartree crucial for predicting chemical reaction rates—is a primary goal [3].

However, the path to this goal is obstructed by the VQE measurement problem, which encompasses all errors that occur during the process of measuring the quantum state to estimate the energy expectation value. These errors include inherent quantum shot noise, readout errors, and noise accumulation during computation, which collectively degrade the precision and accuracy of the final energy estimation [3]. This whitepaper examines the impact of measurement errors on ground state energy estimation, details current mitigation methodologies, and provides a toolkit for researchers aiming to conduct high-precision quantum computational chemistry.

Quantitative Impact of Errors on Estimation Accuracy

The viability of VQE calculations is critically dependent on maintaining hardware error probabilities below specific thresholds. Research quantifying the effect of gate errors on VQEs reveals stringent requirements for quantum chemistry applications.

Table 1: Tolerable Gate-Error Probabilities for Chemical Accuracy

| Condition | Small Molecules (4-14 Orbitals) | Scaling Relation |

|---|---|---|

| Without Error Mitigation | 10â»â¶ to 10â»â´ | ~ NIIâ»Â¹ |

| With Error Mitigation | 10â»â´ to 10â»Â² | ~ NIIâ»Â¹ |

The maximally allowed gate-error probability (p_c) decreases with the number of noisy two-qubit gates (N_II) in the circuit, following a p_c ~ N_II^{-1} relationship [23]. This inverse proportionality means that deeper circuits, necessary for larger molecules, demand exponentially lower error rates. Furthermore, p_c decreases with system size even when error mitigation is employed, indicating that scaling VQEs to larger, more chemically interesting molecules will require significant hardware improvements [23].

Case Study: Precision Measurement for the BODIPY Molecule

Practical techniques have been demonstrated for high-precision measurements on near-term hardware. In a study targeting the BODIPY molecule, researchers addressed key overheads and noise sources to reduce measurement errors by an order of magnitude [3].

The experiment estimated energies for ground (S0) and excited (S1, T1) states in active spaces ranging from 8 to 28 qubits. Key techniques implemented were:

- Locally Biased Random Measurements: Reduced shot overhead by prioritizing measurement settings with a larger impact on the energy estimation.

- Repeated Settings with Parallel Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT): Mitigated readout errors and reduced circuit overhead.

- Blended Scheduling: Accounted for and mitigated time-dependent detector noise.

Table 2: Error Mitigation Results for BODIPY (8-qubit S0 Hamiltonian)

| Mitigation Technique | Absolute Error (Hartree) | Key Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Unmitigated | 1-5% | Baseline error level |

| With QDT & Blending | 0.16% | Order-of-magnitude improvement |

This combination of strategies enabled an estimation error of 0.16% (1.6 × 10â»Â³ Hartree), bringing it to the threshold of chemical precision on a state with a complex Hamiltonian, despite high readout errors on the order of 10â»Â² [3].

Error Mitigation Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Reference-State and Multireference Error Mitigation (REM/MREM)

Reference-state error mitigation (REM) is a cost-effective, chemistry-inspired technique. Its core principle is using a classically solvable reference state to characterize and subtract the noise bias introduced by the hardware.

Experimental Protocol for REM:

- Select a Reference State: Choose a state (e.g., the Hartree-Fock state) with a classically known energy,

E_ref(exact). This state should be easy to prepare on the quantum device [24]. - Prepare and Measure on Quantum Hardware: Prepare the reference state

Ï_refand measure its energyE_ref(noisy)on the noisy quantum processor. - Compute the Error Bias: Calculate the energy difference

ΔE_ref = E_ref(noisy) - E_ref(exact). - Mitigate the Target State: Prepare the target VQE state

Ï(θ), measure its noisy energyE_target(noisy), and apply the correction:E_target(corrected) = E_target(noisy) - ΔE_ref[24].

REM works well for weakly correlated systems where the Hartree-Fock state is a good approximation. However, for strongly correlated systems (e.g., bond-stretching regions), a single determinant is insufficient, limiting REM's effectiveness [24].

Multireference-state error mitigation (MREM) extends this framework. Instead of a single reference, it uses a compact wavefunction composed of a few dominant Slater determinants to better capture the character of strongly correlated ground states.

Experimental Protocol for MREM:

- Generate Multireference State: Use an inexpensive classical method to identify a few important Slater determinants for the target system.

- Prepare State on Quantum Hardware: Efficiently prepare this multireference state using structured quantum circuits, such as those based on Givens rotations, which preserve particle number and spin symmetry [24].

- Compute Exact Energy Classically: Calculate the exact energy

E_MR(exact)for this multireference state using a classical computer. - Apply REM Protocol: Use this multireference state as the reference in the standard REM protocol, measuring its noisy energy

E_MR(noisy)on the hardware and computing the correction biasΔE_MRto mitigate the target VQE state [24].

Informationally Complete (IC) Measurements and Quantum Detector Tomography

Informationally complete (IC) measurements, such as classical shadows, allow for the estimation of multiple observables from the same set of measurements, which is beneficial for measurement-intensive algorithms [3].

Experimental Protocol for IC Measurements with QDT:

- Perform Quantum Detector Tomography: Characterize the readout noise of the device by preparing all computational basis states and measuring them. This builds a noise matrix

Λthat describes the probability of reading outcomejwhen the true state isi[3]. - Execute IC Measurement of the State: Prepare the state of interest (e.g., Hartree-Fock or an ansatz state) and measure it in a random set of bases sufficient to form an informationally complete set.

- Mitigate Readout Errors: Use the noise matrix

Λfrom QDT to correct the raw measurement statistics, producing an unbiased estimate of the ideal probabilities. - Estimate the Energy: Reconstruct the expectation values of the Hamiltonian terms from the corrected statistics.

This workflow, especially when combined with blended scheduling to average over time-dependent noise, has been proven essential for achieving high-precision energy estimation [3].

Diagram 1: High-precision measurement workflow using IC measurements and QDT.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Methods for VQE Experimentation

| Research Reagent | Function & Explanation |

|---|---|

| ADAPT-VQE Ansätze | Iteratively constructed quantum circuits that outperform fixed ansätze like UCCSD, demonstrating superior noise resilience and shorter circuit depths [23]. |

| Givens Rotation Circuits | Structured quantum circuits used to efficiently prepare multireference states for MREM, preserving physical symmetries like particle number [24]. |

| Locally Biased Classical Shadows | An IC measurement technique that reduces shot overhead by biasing the selection of measurement bases toward those more relevant for the specific Hamiltonian [3]. |

| Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT) | A calibration procedure that characterizes the readout error of the quantum device, enabling the mitigation of these errors in post-processing [3]. |

| Hartree-Fock Reference State | A single-determinant state, easily prepared on a quantum computer and classically solvable, serving as the primary reference for the REM protocol [24]. |

| Blended Scheduling | An execution strategy that interleaves circuits for different tasks (e.g., different Hamiltonians, QDT) to average out the impact of time-dependent hardware noise [3]. |

| 1,4-Naphthoquinone | 1,4-Naphthoquinone|CAS 130-15-4|Research Compound |

| Bis(oxalato)chromate(III) | Bis(oxalato)chromate(III), CAS:18954-99-9, MF:C4H4CrO10-, MW:264.06 g/mol |

Measurement error presents a formidable challenge to achieving chemically accurate ground-state energy estimation with the Variational Quantum Eigensolver. The quantitative requirements are strict, with gate-error probabilities needing to be as low as 10â»â¶ to 10â»â´ for small molecules without mitigation [23]. Furthermore, the inverse relationship between tolerable error and circuit depth creates a significant barrier to scaling for larger systems. However, as demonstrated by the BODIPY case study and the development of advanced protocols like MREM, a combination of chemistry-inspired error mitigation, robust measurement strategies, and precise hardware characterization can reduce errors to the threshold of chemical precision on existing devices [24] [3]. For researchers in drug development and quantum chemistry, mastering and applying this growing toolkit of error-aware experimental protocols is not merely an optional optimization—it is a fundamental prerequisite for obtaining reliable scientific results from near-term quantum computers.

Chemical Precision, Shot Overhead, and Circuit Overhead

In the pursuit of quantum advantage for chemical simulations, the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) has emerged as a leading algorithm for near-term quantum devices. A significant bottleneck in its practical execution is the measurement problem, encompassing the prohibitive resources required to estimate molecular energies to a useful accuracy. This technical guide delineates three intertwined core concepts critical to overcoming this challenge: chemical precision, shot overhead, and circuit overhead.

Chemical precision, typically defined as an energy error of 1.6 × 10â»Â³ Hartree, is the accuracy threshold required for predicting chemically relevant reaction rates [25]. Achieving this on noisy quantum hardware is complicated by shot overhead, the exponentially large number of repeated circuit executions (shots) needed to suppress statistical uncertainty, and circuit overhead, the number of distinct quantum circuits that must be compiled and run [26] [25]. This guide synthesizes current research and methodologies aimed at managing these overheads to enable chemically precise quantum chemistry on noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices.

Defining the Core Concepts

Chemical Precision

In quantum computational chemistry, chemical precision refers to the required statistical precision in energy estimation, set at 1.6 × 10â»Â³ Hartree [25]. This value is not arbitrary; it is motivated by the sensitivity of chemical reaction rates to changes in energy barriers. Distinguishing between statistical precision and the exact error of an ansatz state is crucial. An estimation is considered to have achieved chemical precision when its statistical confidence interval is within this bound of the true energy value of the prepared quantum state, a prerequisite for reliable predictions in applications like drug discovery [27].

Shot Overhead

Shot overhead denotes the number of times a quantum circuit must be executed (or "shot") to estimate an observable's expectation value with a desired statistical precision. This overhead is a dominant cost factor. The variance of the estimate scales inversely with the number of shots, meaning that to halve the statistical error, one must quadruple the shot count.

This overhead becomes particularly prohibitive for large molecules, where Hamiltonians comprise thousands of Pauli terms. For instance, as shown in [25], the number of Pauli strings in molecular Hamiltonians grows as ð’ª(Nâ´) with the number of qubits, directly inflating the required number of measurements.

Circuit Overhead

Circuit overhead refers to the number of distinct quantum circuit variants that need to be compiled and executed on the quantum hardware to perform a computation [25]. In VQE, this is often tied to the number of measurement settings required. Each unique Pauli string in a molecular Hamiltonian typically requires a specific set of basis-rotation gates before measurement. A Hamiltonian with thousands of terms would therefore necessitate thousands of distinct circuit configurations, leading to significant compilation and queuing time on shared quantum devices, which is a practical constraint for research and development timelines.

Quantitative Data and Benchmarking

Benchmarking studies provide critical insights into the performance of various strategies and the resource requirements for realistic problems. The tables below consolidate quantitative data from recent research.

Table 1: Performance of Classical Optimizers in Noisy VQE Simulations [28]

| Optimizer Type | Optimizer Name | Performance in Ideal Conditions | Performance in Noisy Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gradient-based | Conjugate Gradient (CG) | Best-performing | Not among best |

| L-BFGS-B | Best-performing | Not among best | |

| SLSQP | Best-performing | Not among best | |

| Gradient-free | COBYLA | Efficient | Best-performing |

| POWELL | Efficient | Best-performing | |

| SPSA | Not specified | Best-performing |

Table 2: Scaling of Pauli Strings in Molecular Hamiltonians [25]

| Number of Qubits | Active Space | Number of Pauli Strings |

|---|---|---|

| 8 | 4e4o | 361 |

| 12 | 6e6o | 1,819 |

| 16 | 8e8o | 5,785 |

| 20 | 10e10o | 14,243 |

| 24 | 12e12o | 29,693 |

| 28 | 14e14o | 55,323 |

Table 3: Sampling Overhead Reduction from Advanced Techniques [26]

| Technique | Key Mechanism | Reported Overhead Reduction |

|---|---|---|

| ShotQC (Full) | Shot distribution + Cut parameterization | Up to 19x |

| ShotQC (Economical) | Trade-off decisions between runtime and overhead | 2.6x (on average) |

Methodologies for Overhead Reduction

Protocol 1: Informationally Complete (IC) Measurements with Locally Biased Randomization

This protocol leverages IC measurements to enable the estimation of multiple observables from the same set of measurement data, thereby reducing both shot and circuit overhead [25] [27].

Detailed Procedure:

- State Preparation: Prepare the quantum state of interest, Ï (e.g., a VQE ansatz state).

- IC-POVM Implementation: Instead of measuring in the Pauli basis, implement an Informationally Complete Positive Operator-Valued Measure (IC-POVM). This involves applying a specific set of basis-rotation circuits to the state.

- Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT): Characterize the noisy measurement process of the device by performing QDT in parallel. This builds a model of the actual measurement effects, which is used to construct an unbiased estimator for the observables [25].

- Locally Biased Sampling: Dynamically allocate more shots to the measurement settings that have a larger impact on the variance of the final energy estimate. This optimization reduces the shot overhead without compromising the informationally complete nature of the data [25].

- Classical Reconstruction: Use the collected IC-POVM data and the noisy measurement model from QDT to classically compute the expectation values for all Pauli terms in the Hamiltonian.

This methodology is central to Algorithmiq's AIM-ADAPT-VQE approach, which uses IC measurements to reduce the number of quantum circuits run during the adaptive ansatz construction process [27].

Protocol 2: Quantum Circuit Cutting with ShotQC

The ShotQC framework addresses the overhead introduced by circuit cutting, a technique that partitions a large quantum circuit into smaller, executable subcircuits [26].

Detailed Procedure:

- Circuit Partitioning: Identify and cut the edges (wires) in the large quantum circuit's tensor network representation, breaking it into

ksmaller subcircuits. - Subcircuit Execution: Instead of executing the original circuit, execute the generated subcircuits. Each subcircuit is run with a variety of injected initial states and measured with different observables, as dictated by the cutting procedure.

- Shot Distribution Optimization (Adaptive Monte Carlo): Dynamically allocate the total shot budget among the different subcircuit configurations. More shots are assigned to configurations that contribute more significantly to the variance of the final reconstructed result.

- Cut Parameterization Optimization: Exploit additional degrees of freedom in the mathematical identity used to reconstruct the original circuit. This optimization further suppresses the variance of the estimator.

- Classical Post-processing: Reconstruct the expectation value of the original, uncut circuit by combining the results from all subcircuit executions according to the cutting formula. The optimizations in steps 3 and 4 ensure this is done with minimal sampling overhead.

Protocol 3: Efficient Grouping and Measurement of Operators

This protocol reduces circuit overhead by designing measurement schemes that evaluate multiple Hamiltonian terms simultaneously.

Detailed Procedure:

- Operator Decomposition: Decompose the target Hamiltonian into a set of operators amenable to simultaneous measurement. For first-quantized TB models, this can be a set of standard-basis (SB) operators; for qubit Hamiltonians, this involves grouping Pauli strings [15].

- Operator Grouping: Group the operators into commuting sets or sets that can be measured with a shared basis-rotation circuit. For SB operators, the grouping cost scales linearly with the number of non-zero elements in the Hamiltonian, offering efficiency [15].

- Circuit Design: For each group, design a single quantum circuit that can measure all operators in that group simultaneously. This could be an extended Bell measurement circuit or a GHZ-state-based circuit that requires at most

NCNOT gates for anN-qubit circuit [15]. - Execution and Estimation: Execute each grouped circuit, collect the measurement statistics, and process the results to extract the expectation values for all operators within the group.

Visualizing Workflows and Relationships

The following diagrams illustrate the logical relationships and experimental workflows described in this guide.

Core Concepts and Mitigation Strategies

IC Measurement Protocol

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This section details the essential "research reagents"—algorithmic tools and software strategies—required to implement the aforementioned protocols in practical experiments.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for VQE Measurement Problem

| Tool / Technique | Category | Primary Function | Key Benefit |

|---|---|---|---|

| IC-POVMs [25] [27] | Measurement Strategy | Enables estimation of multiple observables from a single measurement dataset. | Reduces circuit overhead; provides interface for error mitigation. |

| Locally Biased Random Measurements [25] | Shot Optimization | Dynamically allocates shots to high-impact measurement settings. | Reduces shot overhead while maintaining estimation accuracy. |

| Quantum Circuit Cutting (e.g., ShotQC) [26] | Circuit Decomposition | Splits large circuits into smaller, executable fragments. | Enables simulation of large circuits on smaller quantum devices. |

| PPTT Fermion-to-Qubit Mappings [27] | Qubit Encoding | Generates efficient mappings from fermionic Hamiltonians to qubit space. | Reduces circuit complexity and number of gates, mitigating noise. |

| GHZ/Bell Measurement Circuits [15] | Operator Grouping | Simultaneously measures groups of non-commuting operators (SB operators). | Dramatically reduces the number of distinct circuits required. |

| Parallel Quantum Detector Tomography [25] | Error Mitigation | Characterizes and models device-specific readout noise. | Allows for the construction of an unbiased estimator, improving precision. |

| Acefylline Piperazine | Acefylline Piperazinate|CAS 18833-13-1|RUO | Acefylline piperazinate is a xanthine derivative for research. This product is For Research Use Only and is not intended for diagnostic or personal use. | Bench Chemicals |

| 4-[(E)-2-nitroprop-1-enyl]phenol | 4-[(E)-2-Nitroprop-1-enyl]phenol | 4-[(E)-2-Nitroprop-1-enyl]phenol is a high-purity phenolic research chemical. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

Measuring Molecular Energies: VQE Protocols and Drug Discovery Applications

The accurate calculation of molecular electronic structure is a cornerstone of computational chemistry, materials science, and drug discovery. The molecular Hamiltonian encapsulates all possible energy states of a molecule and solving for its ground-state energy reveals stable molecular configurations, reaction pathways, and key properties. However, the computational cost of solving the electronic Schrödinger equation exactly grows exponentially with system size on classical computers, creating a fundamental bottleneck for simulating anything beyond small molecules.

The Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) has emerged as a promising hybrid quantum-classical algorithm designed to overcome this limitation by leveraging near-term quantum processors. This algorithm is particularly suited for Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) devices, as it employs shallow quantum circuits with optimization handled classically. The VQE framework provides a viable path toward quantum advantage in molecular simulation by mapping the electronic structure problem onto qubits. This technical guide details the theoretical foundation and practical implementation of constructing the molecular Hamiltonian for quantum computation, framing this process within broader VQE research.

Theoretical Foundation: The Molecular Electronic Structure Problem

The goal of electronic structure calculation is to solve the time-independent electronic Schrödinger equation [29]: $$He \Psi(r) = E \Psi(r)$$ Here, (He) represents the electronic Hamiltonian, (E) is the total energy, and (\Psi(r)) is the electronic wave function. In the Born-Oppenheimer approximation, which treats atomic nuclei as fixed point charges, the Hamiltonian depends parametrically on nuclear coordinates [29].

In first quantization, the molecular Hamiltonian for (M) nuclei and (N) electrons is expressed in atomic units as [30]: $$ H = -\sumi \frac{\nabla{\mathbf{R}i}^2}{2Mi} - \sumi \frac{\nabla{\mathbf{r}i}^2}{2} - \sum{i,j} \frac{Zi}{|\mathbf{R}i - \mathbf{r}j|} + \sum{i,j>i} \frac{Zi Zj}{|\mathbf{R}i - \mathbf{R}j|} + \sum{i,j>i} \frac{1}{|\mathbf{r}i - \mathbf{r}_j|} $$ The terms represent, in order: the kinetic energy of the nuclei, the kinetic energy of the electrons, the attractive potential between nuclei and electrons, the repulsive potential between nuclei, and the repulsive potential between electrons. This form is computationally intractable for all but the smallest systems, necessitating a transition to the second-quantization formalism for practical quantum computation.

The Second-Quantized Fermionic Hamiltonian

In second quantization, the electronic Hamiltonian is expressed using creation ((cp^\dagger)) and annihilation ((cp)) operators that act on molecular orbitals. For a set of (M) spin orbitals, the Hamiltonian takes the form [29]: $$ H = \sum{p,q} h{pq} cp^\dagger cq + \frac{1}{2} \sum{p,q,r,s} h{pqrs} cp^\dagger cq^\dagger cr cs $$ The coefficients (h{pq}) and (h{pqrs}) are one- and two-electron integrals, which are precomputed classically using the Hartree-Fock method. These integrals describe the electronic interactions within the chosen basis set [29]. The Hartree-Fock method provides an initial mean-field solution by treating electrons as independent particles moving in the average field of other electrons, yielding optimized molecular orbitals as a linear combination of atomic orbitals [29].

Mapping the Fermionic Hamiltonian to Qubits

Quantum computers operate on qubits, which follow bosonic statistics. To simulate fermionic systems, the fermionic Hamiltonian must be mapped to a qubit Hamiltonian acting on the Pauli group ({I, X, Y, Z}). This is achieved through transformations such as the Jordan-Wigner or parity encoding, which preserve the anti-commutation relations of the original fermionic operators [29].

The Jordan-Wigner transformation maps fermionic creation and annihilation operators to Pauli strings with phase factors [29]. After this transformation, the Hamiltonian becomes a linear combination of Pauli terms: $$ H = \sumj Cj \otimesi \sigmai^{(j)} $$ Here, (Cj) is a scalar coefficient, and (\sigmai^{(j)}) represents a Pauli operator ((I, X, Y, Z)) acting on qubit (i). The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow from molecular structure to a qubit Hamiltonian.

Figure 1: Workflow for constructing a qubit Hamiltonian from molecular structure. The process begins with defining the molecule, proceeds through the Hartree-Fock method to compute electronic integrals, and culminates in mapping the fermionic operators to qubits via a transformation like Jordan-Wigner.

Integration with the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE)

The VQE algorithm uses the variational principle to approximate the ground state energy (Eg) of a Hamiltonian (H) [14] [7]. A parameterized quantum circuit (ansatz) prepares a trial state (|\Psi(\boldsymbol{\theta})\rangle), whose energy expectation value is measured on a quantum processor. A classical optimizer adjusts the parameters (\boldsymbol{\theta}) to minimize this energy [30] [7]: $$ Eg \leq \min_{\boldsymbol{\theta}} \frac{\langle \Psi(\boldsymbol{\theta}) | H | \Psi(\boldsymbol{\theta}) \rangle}{\langle \Psi(\boldsymbol{\theta}) | \Psi(\boldsymbol{\theta}) \rangle} $$ The VQE is considered a leading algorithm for the NISQ era because it employs relatively short quantum circuit depths, making it more resilient to noise than algorithms like Quantum Phase Estimation (QPE) [7]. Recent research focuses on enhancing VQE with techniques like Quantum Gaussian Filters (QGF) to improve convergence speed and accuracy under noisy conditions [7].

Experimental Protocols & Benchmarking

Successful application of VQE requires careful selection of computational parameters. A benchmarking study on small aluminum clusters (Alâ‚‚, Al₃â») systematically evaluated key parameters [31]. The results demonstrated that VQE can achieve remarkable accuracy, with percent errors consistently below 0.2% compared to classical computational chemistry databases when parameters are properly optimized.

Table 1: Key Parameters for VQE Experiments in Molecular Energy Calculation [31]

| Parameter Category | Specific Options/Settings | Impact on Calculation |

|---|---|---|

| Classical Optimizers | COBYLA, SPSA, L-BFGS-B, SLSQP | Critical for convergence efficiency and speed. |

| Circuit Types (Ansätze) | Unitary Coupled Cluster (UCC), Hardware-Efficient | Impacts accuracy, circuit depth, and trainability. |

| Basis Sets | STO-3G, 6-31G, cc-pVDZ | Higher-level sets increase accuracy and qubit count. |

| Simulator Types | Statevector, QASM | Idealized simulation vs. realistic sampling. |

| Noise Models | IBM noise models (e.g., for ibmq_manila) |

Simulates realistic hardware conditions. |

Detailed VQE Protocol for Molecular Systems

- Molecule Specification: Define the molecular geometry by providing atomic symbols and nuclear coordinates in atomic units. For example, a water molecule can be defined as symbols =

["H", "O", "H"]and coordinates =np.array([[-0.0399, -0.0038, 0.0], [1.5780, 0.8540, 0.0], [2.7909, -0.5159, 0.0]])[29]. - Qubit Hamiltonian Generation: Use a quantum chemistry library (e.g., PennyLane's

qchemmodule) to generate the qubit Hamiltonian. Themolecular_hamiltonian()function automates the Hartree-Fock calculation, integral computation, and fermion-to-qubit transformation, returning the Hamiltonian as a linear combination of Pauli strings and the number of required qubits [29]. - Ansatz Selection and Initialization: Choose an ansatz such as the Unitary Coupled Cluster with Singles and Doubles (UCCSD), which is chemically motivated, or a hardware-efficient ansatz for reduced circuit depth. Initialize the parameters, often to zero or small random values [30].

- Measurement and Optimization Loop:

- The parameterized quantum circuit is executed, and the expectation value of the Hamiltonian (\langle H \rangle) is measured.

- This energy value is fed to a classical optimizer, which determines a new set of parameters.

- The process repeats until convergence in the energy is achieved.

Table 2: Key Tools and Resources for Molecular Hamiltonian Construction and VQE Simulation

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| PennyLane [29] | Software Library | A cross-platform library for differentiable quantum computations. | Building molecular Hamiltonians and training VQEs via its qchem module. |

| Qiskit [30] | Software Framework | An open-source SDK for working with quantum computers at the level of circuits, pulses, and algorithms. | Implementing VQE algorithms and running simulations on local clusters or IBM hardware. |

| OpenMolcas [32] | Quantum Chemistry Software | An ab initio quantum chemistry software package. | Performing complete active space self-consistent field (CASSCF) calculations for molecular orbitals. |

| Gaussian 16 [32] | Quantum Chemistry Software | A computational chemistry program for electronic structure modeling. | Molecular geometry optimization and calculation of properties under applied electric fields. |

| Quantum Hardware/Simulators (e.g., IBM, Google) | Hardware/Service | Physical quantum processors or high-performance simulators. | Running quantum circuits for energy expectation measurement in VQE. |

Constructing the molecular Hamiltonian and mapping it to a qubit representation is a critical, foundational step for quantum computational chemistry. This process, which integrates traditional quantum chemistry methods with novel quantum mappings, enables the use of hybrid algorithms like the VQE to tackle the long-standing challenge of electronic structure calculation. While current hardware limitations restrict simulations to small molecules, rapid progress in quantum error correction, algorithmic efficiency, and hardware fidelity is paving the way for practical applications in drug discovery and materials science. The synergy between advanced classical computational methods and emerging quantum capabilities holds the potential to revolutionize our approach to modeling complex molecular systems.

In the realm of the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE), a hybrid quantum-classical algorithm designed for Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) devices, the measurement problem presents a significant roadblock to practical application [33] [14]. The VQE aims to find the ground state energy of a quantum system, such as a molecule, by minimizing the expectation value of its Hamiltonian [11]. A central challenge is the high overhead associated with the repetitive measurements required to estimate this expectation value, which grows rapidly with system complexity and hampers the simulation of mid- and large-sized molecules [33] [34].

The ansatz state is a parameterized quantum circuit that serves as a trial wavefunction, preparing candidate quantum states for measurement [11] [14]. The choice and preparation of the ansatz are pivotal, as this state is measured to obtain the energy expectation value, which the classical optimizer then uses to update the parameters in a feedback loop. The quality of the ansatz directly influences the algorithm's accuracy, efficiency, and convergence. This guide delves into the core role of the ansatz state within the VQE measurement problem, providing a technical examination for researchers and scientists seeking to implement these methods in fields like drug development.

Fundamental Principles of the VQE Ansatz

Mathematical Formulation

The VQE operates on the variational principle, which states that for any trial wavefunction ( |\Psi(\boldsymbol{\theta})\rangle ), the expectation value of the Hamiltonian ( \hat{H} ) is an upper bound to the true ground state energy ( Eg ) [11] [14]: [ Eg \leq E[\Psi(\boldsymbol{\theta})] = \frac{\langle\Psi(\boldsymbol{\theta})|\hat{H}|\Psi(\boldsymbol{\theta})\rangle}{\langle\Psi(\boldsymbol{\theta})|\Psi(\boldsymbol{\theta})\rangle} = \langle \hat{H} \rangle_{\hat{U}(\boldsymbol{\theta})} ]

The objective of the VQE is to find the parameters ( \boldsymbol{\theta} ) that minimize this expectation value [11]: [ \min{\boldsymbol{\theta}} \langle \hat{H} \rangle{\hat{U}(\boldsymbol{\theta})} = \min_{\boldsymbol{\theta}} \langle 0 | \hat{U}^{\dagger}(\boldsymbol{\theta}) \hat{H} \hat{U}(\boldsymbol{\theta}) | 0 \rangle ]

Here, ( \hat{U}(\boldsymbol{\theta}) ) is the parameterized unitary operation that prepares the ansatz state from an initial state ( |0\rangle ), which is typically the Hartree-Fock state in quantum chemistry applications [11].

The Measurement Challenge in VQE

To compute the expectation value, the Hamiltonian must be expressed as a sum of Pauli strings after a fermion-to-qubit mapping [34]: [ H = \sumi wi Pi ] where ( Pi ) is a Pauli string and ( w_i ) is the corresponding weight.

The number of these terms grows as ( \order{N^4} ) for molecular systems with ( N ) spin-orbitals, creating a major bottleneck [34]. Measuring each term requires separate quantum circuit executions, often in different bases, making the development of efficient ansatz states and measurement protocols critical for reducing this overhead.

Types of Ansätze and Their Characteristics

The choice of ansatz is a critical decision in VQE implementation, balancing expressibility, circuit depth, and chemical accuracy. The following table summarizes the primary ansatz types used in quantum chemistry simulations.

Table 1: Comparison of primary ansatz types used in VQE simulations

| Ansatz Type | Key Features | Measurement Considerations | Best-Suited Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

Hardware-Efficient (e.g., EfficientSU2) |

- Uses native gate sets for specific hardware- Low-depth circuits- Minimal entanglement | - Reduced noise sensitivity- May require more parameters to converge- Less systematic construction | - Near-term devices with limited coherence times- Problems without strong chemical constraints |

Chemistry-Inspired (e.g., UCCSD) |

- Based on fermionic excitation operators- Physically motivated- Systematically improvable | - Higher circuit depth- May require Trotterization- More accurate for molecular systems | - Quantum chemistry problems- Molecular ground state energy calculations- High-accuracy simulations |

| Problem-Specific | - Leverages problem symmetries- Custom-designed for specific systems- Optimized parameter count | - Requires domain knowledge- Can reduce measurement overhead- Potentially lower circuit depth | - Systems with known symmetries- Specialized applications like materials science |

Ansatz Selection Protocol

Selecting the appropriate ansatz requires careful consideration of the target problem, available quantum resources, and desired accuracy. The following workflow provides a systematic approach to ansatz selection.

Figure 1: Decision workflow for selecting an appropriate ansatz type based on problem constraints and requirements.

Implementation Guidelines

For quantum chemistry problems, the UCCSD ansatz is generally preferred when hardware constraints allow, as it provides superior chemical accuracy [11]. The implementation follows:

- Initial State Preparation: Begin with the Hartree-Fock state using the

HartreeFockclass [11]. - Ansatz Definition: Construct the UCCSD ansatz with appropriate mapping to qubits:

ansatz = UCCSD(num_spatial_orbitals, num_particles, mapper, initial_state=init_state)[11]. - Parameter Initialization: Typically start with zero initial parameters or small random values.

When hardware limitations dominate, the hardware-efficient approach using EfficientSU2 provides a practical alternative with lower circuit depth: ansatz = EfficientSU2(num_qubits=qubit_op.num_qubits, entanglement='linear', initial_state=init_state) [11].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Standard VQE Measurement Protocol

The complete VQE workflow integrates ansatz preparation with measurement protocols in a hybrid quantum-classical loop, as shown below.

Figure 2: Complete VQE workflow showing the integration of ansatz preparation with measurement protocols.

Advanced Measurement Protocols

Recent research has developed sophisticated measurement protocols to address the overhead problem. The State Specific Measurement Protocol offers significant improvements [33] [34]:

- Protocol Overview: This method computes an approximation of the Hamiltonian expectation value by measuring cheap grouped operators directly and estimating residual elements through iterative measurements in different bases [34].

- Key Innovation: The protocol utilizes operators defined by the Hard-Core Bosonic approximation, which encode electron-pair annihilation and creation operators. These can be decomposed into just three self-commuting groups measurable simultaneously [34].

- Performance: Applied to molecular systems, this method achieves a reduction of 30% to 80% in both the number of measurements and gate depth in measuring circuits compared to state-of-the-art methods [33].

Table 2: Quantitative comparison of measurement reduction protocols

| Measurement Protocol | Measurement Reduction | Key Mechanism | Implementation Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|

| State Specific Protocol [33] | 30-80% | Hard-Core Bosonic operators & iterative residual estimation | Medium |

| Qubit-Wise Commuting (QWC) [34] | Moderate | Groups Pauli strings where each qubit operator commutes | Low |

| Fully Commuting (FC) [34] | Higher than QWC | Groups normally commuting operators transformed to QWC form | High |

| Fermionic-Algebra-Based (F3) [34] | Varies | Leverages fermionic commutativity before qubit mapping | Medium-High |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Implementation of VQE with effective ansatz states requires both software and methodological components. The following table details key resources for experimental implementation.

Table 3: Essential research reagents and tools for VQE ansatz implementation

| Tool/Component | Function | Example Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Data Generator | Generates electronic structure problem from molecular definition | PySCFDriver for computing molecular integrals [11] |

| Qubit Mapper | Maps fermionic Hamiltonians to qubit representations | ParityMapper for fermion-to-qubit transformation [11] |

| Ansatz Circuit | Parameterized quantum circuit for state preparation | UCCSD for chemically accurate ansatz [11] |

| Classical Optimizer | Updates variational parameters to minimize energy | SLSQP optimizer for gradient-based optimization [11] |

| Estimator | Evaluates expectation values of observables | Estimator with approximation capabilities [11] |

| Measurement Grouping | Groups commuting Pauli terms to reduce measurements | Recursive Largest First (RLF) for clique cover [34] |

| Terodiline | Terodiline, CAS:15793-40-5, MF:C20H27N, MW:281.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 5-Bromo-N,N-Dimethyltryptamine | 5-Bromo-N,N-dimethyltryptamine|High-Purity Research Chemical | 5-Bromo-N,N-dimethyltryptamine for research use only. Explore its applications in neuroscience and pharmacology. Not for human or veterinary use. |

The ansatz state represents both a challenge and opportunity within the VQE measurement problem. While its preparation and measurement contribute significantly to the computational overhead, strategic selection and implementation of ansätze can dramatically reduce resource requirements. The emerging methodologies, such as the State Specific Measurement Protocol that leverages problem-specific insights to reduce measurements by up to 80%, demonstrate the rapid advancement in this field [33].

For researchers in drug development and materials science, the careful integration of chemically motivated ansätze like UCCSD with advanced measurement protocols provides a viable path toward simulating increasingly complex molecular systems on near-term quantum devices. As hardware continues to improve and algorithms become more sophisticated, the preparation and measurement of ansatz states will remain a critical focus for achieving practical quantum advantage in electronic structure calculations.

Accurate measurement of quantum observables represents a fundamental challenge in realizing the potential of near-term quantum computing for chemical and pharmaceutical applications. Within the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) framework, the measurement process often dominates resource requirements and introduces significant errors in molecular energy estimation. This technical guide comprehensively examines two principal strategies for optimizing quantum measurements: Pauli term grouping and Informationally Complete (IC) approaches. By synthesizing recent advances in commutative grouping algorithms and detector tomography techniques, we provide researchers with a structured framework for implementing these methods, complete with quantitative performance comparisons and detailed experimental protocols. Our analysis demonstrates that hybrid grouping strategies like GALIC can reduce estimator variance by 20% compared to conventional qubit-wise commuting approaches, while IC measurements enable error suppression to 0.16% in molecular energy estimation—sufficient for approaching chemical accuracy in pharmaceutical applications.

The Variational Quantum Eigensolver has emerged as a promising algorithm for molecular energy calculations on noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices, with particular relevance to drug discovery and development. However, VQE's practical implementation faces a critical bottleneck: the efficient and accurate measurement of molecular Hamiltonians, which typically require evaluation of thousands of individual Pauli terms [35]. For an N-qubit system, the number of distinct operator expectations scales as O(Nâ´) for basic VQE implementations and up to O(Nâ¸) for adaptive approaches like ADAPT-VQE [35]. Each operator requires thousands of measurements, necessitating millions of state preparations to obtain energy estimates within chemical accuracy (1.6 × 10â»Â³ Hartree) [3].

The core challenge lies in estimating the expectation value ⟨ψ|H|ψ⟩ for molecular Hamiltonians decomposed as H = Σᵢ cᵢPᵢ, where Pᵢ are Pauli operators and cᵢ are real coefficients [35]. Quantum computers estimate these expectations through repeated state preparation and measurement, but inherent noise, limited sampling statistics, and circuit overhead create significant obstacles to achieving pharmaceutical-grade accuracy in molecular simulations. This whitepaper addresses these challenges through a systematic examination of advanced measurement strategies, providing researchers with implementable solutions for drug development applications.

Pauli Term Grouping Strategies

Theoretical Foundations

Pauli term grouping strategies reduce measurement overhead by simultaneously measuring multiple compatible operators from the target observable. Two primary commutation relations form the basis for most grouping approaches:

- Fully Commuting (FC) Groups: Operators that commute according to the standard commutation relation [Páµ¢, Pâ±¼] = 0. FC grouping offers the lowest estimator variances but requires heavily entangled diagonalization circuits that are susceptible to noise in NISQ devices [35].

- Qubit-Wise Commuting (QWC) Groups: Operators that commute qubit-by-qubit, meaning each corresponding single-qubit Pauli operator commutes. QWC groups require no entangling operations for measurement but yield higher estimator variances compared to FC approaches [35].

The fundamental tradeoff between these approaches has motivated the development of hybrid strategies that interpolate between FC and QWC to balance variance reduction with circuit complexity.

Grouping Methodologies

Table 1: Comparison of Pauli Grouping Strategies

| Strategy | Commutation Relation | Circuit Complexity | Variance | Error Resilience |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fully Commuting (FC) | Standard commutation | High (entangling gates) | Lowest | Low |

| Qubit-Wise Commuting (QWC) | Qubit-by-qubit | None (local ops only) | Highest | High |

| Generalized Backend-Aware (GALIC) | Hybrid FC/QWC | Adaptive | Intermediate | Context-aware |

Advanced grouping algorithms extend beyond basic commutative relations through several innovative approaches:

- Overlapping Commuting Groups: Unlike traditional disjoint grouping, overlapping strategies allow operators to appear in multiple groups, enabling additional variance reduction through canceling variance terms with supplementary commuting operators [35].

- Hardware-Aware Grouping: These approaches consider device-specific characteristics including qubit connectivity, gate fidelity, and measurement error rates. The GALIC framework dynamically adapts grouping strategy based on backend noise profiles and connectivity constraints [35] [36].

- Iterative Optimization: Advanced implementations employ adaptive variance estimation to refine grouping decisions based on empirical performance, progressively optimizing measurement assignments across groups [35].

Implementation Framework

The GALIC (Generalized backend-Aware pauLI Commutation) framework provides a systematic approach for implementing hybrid grouping strategies. Its algorithmic workflow integrates multiple decision factors:

Diagram 1: GALIC grouping workflow (81 characters)

The GALIC framework processes Hamiltonians through the following stages:

- Hamiltonian Decomposition: The target Hamiltonian is decomposed into Pauli operators with coefficients cáµ¢.

- Device Characterization: Qubit connectivity graphs and noise profiles are extracted from device calibration data.

- Hybrid Commutation Analysis: Operators are analyzed using context-aware commutation relations that interpolate between strict FC and QWC.