Quantum Algorithms for NMR Shielding Computation: Current Methods, Breakthroughs, and Future Directions for Researchers

This article explores the rapidly evolving landscape of quantum computing applications for calculating Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) shielding constants—a critical parameter in molecular structure elucidation for drug development and materials...

Quantum Algorithms for NMR Shielding Computation: Current Methods, Breakthroughs, and Future Directions for Researchers

Abstract

This article explores the rapidly evolving landscape of quantum computing applications for calculating Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) shielding constants—a critical parameter in molecular structure elucidation for drug development and materials science. It provides a comprehensive analysis covering the foundational principles of why NMR simulation is a computationally hard problem classically and a natural candidate for quantum advantage. The review details cutting-edge methodological approaches, including Google's recently announced 'Quantum Echoes' algorithm and machine learning-enhanced quantum-classical hybrids. It further examines the significant challenges in optimization and error correction, and provides a comparative validation of quantum against state-of-the-art classical methods like CCSD(T) and machine learning models. Aimed at researchers and pharmaceutical professionals, this resource synthesizes the current state of the field, its practical utility, and a forward-looking perspective on achieving scalable, fault-tolerant quantum computation for real-world chemical problems.

The Quantum Imperative: Why NMR Shielding Simulation is a Natural Fit for Quantum Computers

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy is a pivotal analytical technique in chemistry and structural biology, used to determine molecular structure and identify substances. The computational simulation of NMR spectra from first principles is a critical, yet formidable, task for classical computers. As research into quantum computing advances, this simulation problem has emerged as a prime candidate for demonstrating a practical quantum advantage, where quantum computers could outperform their classical counterparts. Understanding the nature and extent of the classical computational bottleneck is therefore essential. This application note details the specific challenges of exact NMR spectral simulation, provides protocols for benchmarking classical solvers, and frames these challenges within the ongoing pursuit of quantum algorithmic solutions.

The Core Computational Problem in NMR Simulation

At its heart, simulating an NMR spectrum involves calculating the spectral function, a mathematical description of the signal measured in an NMR experiment [1]. For a molecule in solution, the key object is the spin Hamiltonian, which describes the system of interacting atomic nuclei within a magnetic field [2]:

The first term represents the Zeeman interaction between nuclei and the external magnetic field, where γₗ is the gyromagnetic ratio and δₗ is the chemical shift. The second term represents the indirect spin-spin coupling (Jₖₗ) between nuclei [2].

The spectral function, C(ω), which consists of a series of Lorentzian peaks, must then be computed. It is proportional to [2]:

Here, M± are the raising and lowering operators for the total nuclear spin, |Eₙ⟩ and |Eₘ⟩ are energy eigenstates of the Hamiltonian, and η is a broadening parameter that models signal decay and spectrometer resolution [2].

The direct approach to this calculation, exact diagonalization of the Hamiltonian, is where the classical bottleneck becomes apparent. The Hamiltonian possesses a symmetry due to the conservation of total spin along the Z-axis, allowing it to be written in block-diagonal form. The largest block has a dimension ð’Ÿ that scales combinatorially with the number of active nuclei, N [2]:

Consequently, the memory required for an exact calculation scales as ð’ª(2²ᴺ/N), and the computational time scales as ð’ª(2³ᴺ/N³áŸÂ²) [2]. This scaling is the root of the exponential wall faced by classical computers.

Table 1: Key Interactions in the NMR Spin Hamiltonian

| Interaction | Mathematical Form | Physical Origin | Impact on Spectrum |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zeeman Effect | -γₗ(1+δₗ)BzÎᶻₗ |

Interaction of nuclear magnetic moments with the external static magnetic field. | Determines the base Larmor frequency of nuclei. |

| Chemical Shift | δₗ (within Zeeman term) |

Shielding of nuclei by the surrounding electron cloud. | Causes frequency shifts, providing chemical environment fingerprints. |

| J-Coupling | 2Ï€ Jâ‚–â‚— ðˆÌ‚â‚– · ðˆÌ‚â‚— |

Indirect through-bond spin-spin coupling mediated by bonding electrons. | Creates fine structure (multiplets) in the spectrum, revealing connectivity. |

Quantitative Analysis of the Classical Bottleneck

The combinatorial scaling of the Hamiltonian's Hilbert space means that adding just one more spin-1/2 nucleus to a molecule approximately doubles the memory required to represent the system and more than doubles the computation time. For small molecules, this is manageable. However, for larger molecules, the computational demands increase significantly, pushing the limits of even the most powerful classical computers [1].

Table 2: Computational Resource Scaling for Exact NMR Simulation

| Number of Spin-1/2 Nuclei (N) | Approximate Dimension of Largest Block (ð’Ÿ) | Memory Requirement (Approx.) | Implication for Classical Computation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 6 | ~1 KB | Trivial |

| 8 | 70 | ~10 KB | Easy |

| 12 | 924 | ~1 MB | Manageable |

| 16 | 12,870 | ~100 MB | Feasible with significant resources |

| 20 | 184,756 | ~10 GB | Becoming prohibitive for exact methods |

| 24 | 2.7 million | ~1 TB | Effectively intractable for exact diagonalization |

This exponential scaling is not just theoretical. Recent benchmark studies of a highly optimized classical solver revealed that while it performs accurately across a broad range of experimentally realistic scenarios, its performance begins to falter for a specific class of molecules with unusual properties, such as particularly strong spin-spin interactions [1]. These complex molecules, with intricate interactions between atomic nuclei, serve as crucial test cases for evaluating the potential of quantum computing [1]. The identification of these molecular bottlenecks is a key step towards demonstrating a practical quantum advantage in this field [1].

Methodologies and Protocols for Classical Simulation

Given the infeasibility of exact diagonalization for all but the smallest systems, a variety of approximation methods and simulation protocols have been developed. These form the toolkit for classical NMR simulation.

Protocol: Exact Simulation for Small Spin Systems

This protocol is adapted from methodologies used in zero- and ultra-low field NMR simulation, which provide a clear, step-by-step process for spectral calculation [3].

- Define the Spin System: Identify the number of spins

Nand their types (e.g., ¹H, ¹³C). Obtain all relevant NMR parameters: the gyromagnetic ratiosγₗ, the chemical shiftsδₗ, and the scalar coupling constantsJₖₗ[3]. - Construct the Spin Hamiltonian: Using the parameters from step 1, build the full Hamiltonian matrix in a suitable basis (e.g., the product basis) [3].

- Compute the System's Energy Levels: Perform exact diagonalization of the Hamiltonian to find its eigenvalues

Eₙand eigenvectors|Eₙ⟩[3]. - Define the Initial State Density Matrix: Typically, this represents the state of the system after a radiofrequency pulse, often related to a deviation from thermal equilibrium [3].

- Propagate the Density Matrix: Calculate the time evolution of the density matrix,

Ï(t), under the influence of the Hamiltonian [3]. - Calculate the Observable Signal: The detected NMR signal is proportional to the expectation value of a detector operator (e.g.,

Mâº) [3]. - Generate the Spectrum: Apply a Fourier transform to the time-domain signal to obtain the frequency-domain spectrum

C(ω)[3].

Diagram 1: Exact Simulation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Software and Computational Tools for NMR Simulation

| Tool / 'Reagent' | Category | Primary Function | Key Application Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exact Diagonalization Solver | Core Algorithm | Directly computes eigenvalues/eigenvectors of the full spin Hamiltonian. | Use is restricted to small N (N ≲ 20 spins) due to exponential scaling [2]. |

| Symmetry-Adapted Algorithms | Optimization | Exploits molecular symmetries (e.g., SU(2)) to reduce the effective Hilbert space dimension [2]. | Can be counterproductive for very small molecules due to combinatorial overhead [2]. |

| QUEST Software | Specialized Simulator | Exact simulation of solid-state NMR spectra for quadrupolar nuclei [4]. | Employs fast powder averaging; valid across all regimes from high-field NMR to NQR [4]. |

| SpinDynamica/Spinach | Simulation Package | High-level NMR simulation environments for Mathematica and MATLAB [3]. | Powerful for building intuition and simulating complex pulse sequences; best used after understanding core principles [3]. |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | Quantum Chemistry Method | Calculates NMR parameters (shielding constants, J-couplings) from molecular structure [5]. | A ubiquitous, cost-effective ab initio method; accuracy depends on functional and basis set choice [5]. |

| 2-Methyl-1,1-bis(2-methylpropoxy)propane | 2-Methyl-1,1-bis(2-methylpropoxy)propane|C12H26O2 | 2-Methyl-1,1-bis(2-methylpropoxy)propane (C12H26O2) is a high-purity solvent for advanced research. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for diagnostic or personal use. | Bench Chemicals |

| 3-(4-Aminophenyl)-1-(4-chlorophenyl)urea | 3-(4-Aminophenyl)-1-(4-chlorophenyl)urea|CAY-10089-5|RUO | 3-(4-Aminophenyl)-1-(4-chlorophenyl)urea is a urea-based research chemical. It is for Research Use Only (RUO) and not for human or veterinary diagnostics or therapeutic use. | Bench Chemicals |

The Path to Quantum Advantage

The severe exponential scaling of classical resources has established the exact simulation of NMR spectra as a candidate problem for demonstrating a useful quantum advantage. The natural mapping between the degrees of freedom of a molecular spin system and the qubits of a quantum processor makes this a particularly apt application [2].

Recent research has focused on rigorously defining this advantage by benchmarking highly optimized classical solvers. One such study found that a specific classical solver performs well in most common experimental regimes, except for molecules with "certain unusual features" [1] [2]. This pinpointing of a specific weakness in classical methods helps define a clear path forward for quantum computing research. For instance, molecules containing phosphorus with unusually strong spin-spin interactions have been identified as a potential early target [2].

Furthermore, new quantum-inspired NMR techniques are emerging. Google's research on "quantum echoes" (a type of out-of-time-order correlation or OTOC) demonstrates a quantum algorithm with an associated advantage: a measurement that took their quantum computer 2.1 hours would take a leading supercomputer approximately 3.2 years [6]. While this algorithm was demonstrated on a model system, it has been directly linked to probing molecular structure via NMR, suggesting a pathway to practical utility [6].

The relationship between the core classical bottleneck and the potential for a quantum solution can be visualized as follows:

Diagram 2: From Bottleneck to Quantum Advantage

The classical challenge of exact NMR spectral simulation presents a clear and significant computational bottleneck rooted in the exponential scaling of the spin Hamiltonian's Hilbert space. While sophisticated classical approximation methods and optimized solvers can accurately simulate a wide range of molecules, they inevitably encounter fundamental limitations with increasing system size and complexity. This precise delineation of the classical boundary, however, is invaluable. It provides a well-defined benchmark and a set of target problems for the development of quantum algorithms. The ongoing research, from benchmarking classical solvers to developing new quantum algorithms like "quantum echoes," underscores that the simulation of NMR spectra is a prime candidate for achieving a practical quantum advantage, potentially revolutionizing computational chemistry and drug development in the process.

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy provides unparalleled insight into molecular structure and dynamics through the detection of nuclear spin interactions. Conventional computation of NMR parameters, particularly shielding constants, relies heavily on density functional theory (DFT) calculations, which become computationally prohibitive for large molecular systems or when high-throughput screening is required [7]. The emergence of quantum computing offers a transformative pathway for quantum chemistry simulations, potentially providing exponential speedups for solving the electronic structure problems that underpin NMR parameter prediction.

This application note details the theoretical framework and practical methodologies for mapping molecular nuclear spin systems onto quantum processor architectures. We focus specifically on the fermion-to-qubit mapping problem, which represents a critical bridge between molecular Hamiltonians and their implementation on quantum hardware. By providing explicit protocols and benchmarking data, we aim to equip computational researchers and drug development professionals with the tools necessary to leverage quantum computing for advancing NMR shielding constant computation.

Theoretical Foundation

Molecular Spin Hamiltonians

The accurate computation of NMR shielding constants begins with solving the electronic structure problem, which defines the molecular environment surrounding nuclear spins. The fundamental Hamiltonian incorporates both electronic and nuclear degrees of freedom:

[\mathcal{H} = \sum{i,j}\mathbf{S}iJ{ij}\mathbf{S}j + \sumi \mathbf{S}iAi\mathbf{S}i + \mathbf{B}\sumi\mathbf{g}i\mathbf{S}_i]

where (Si) represent spin vector operators, (J{ij}) denotes 3×3 matrices describing pair coupling between spins, (A{ij}) represents 3×3 anisotropy matrices, (B) is the external magnetic field, and (gi) is the g-tensor [8]. This Hamiltonian captures the essential interactions governing NMR phenomena, including Heisenberg exchange, Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interactions, anisotropic exchanges, and Zeeman effects in external magnetic fields.

For molecular systems, the electronic Hamiltonian in second quantization form provides the foundation for property calculations:

[\mathcal{H} = \sum{pq} h{pq} ap^\dagger aq + \frac{1}{2} \sum{pqrs} h{pqrs} ap^\dagger aq^\dagger ar as]

where (h{pq}) and (h{pqrs}) are one- and two-electron integrals, and (ap^\dagger) and (ap) are fermionic creation and annihilation operators. This representation directly facilitates the calculation of NMR shielding tensors through response property formulations implemented in quantum chemistry packages such as ORCA [9] and ADF [10].

Fermion-to-Qubit Mapping Strategies

The transformation of fermionic operators to qubit operators represents a crucial step in implementing quantum chemistry simulations on quantum processors. Several mapping strategies have been developed, each with distinct advantages for specific molecular architectures:

Jordan-Wigner Transformation: This mapping preserves locality in one-dimensional systems but introduces non-local string operators in higher dimensions, increasing circuit depth [11]. The transformation is defined as: [ aj^\dagger = \left(\prod{k=1}^{j-1} Zk\right) \frac{Xj - iYj}{2}, \quad aj = \left(\prod{k=1}^{j-1} Zk\right) \frac{Xj + iYj}{2} ] where (Xj), (Yj), and (Z_j) are Pauli operators acting on qubit (j).

Bravyi-Kitaev Transformation: This approach offers improved locality properties compared to Jordan-Wigner, reducing the operator weight from (O(N)) to (O(\log N)) for some terms, thereby providing more efficient simulation circuits [11].

Auxiliary Fermion Methods: Recent advances introduce auxiliary fermions or enlarged spin spaces to create local fermion-to-qubit mappings in higher dimensions ((>)1D), at the expense of introducing additional constraints that must be enforced throughout the computation [11].

The introduction of auxiliary fermions enables the representation of local fermion Hamiltonians as local spin Hamiltonians, though this requires careful treatment of the additional constraints through Gauss laws and parity considerations [11].

Computational Protocols

Classical NMR Shielding Calculation Workflow

Table 1: Key Software Tools for NMR Shielding Calculations

| Tool | Application | Methodology | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| ORCA | NMR shielding & J-couplings | DFT/GIAO with various functionals & basis sets | [9] |

| ADF | NMR analysis with NBO/NLMO | DFT with localized orbital analysis | [10] |

| SpinDrops | Spin dynamics visualization | DROPS representation & quantum spin simulator | [12] |

| BMRB | Experimental NMR data repository | Curated database of biomolecular NMR data | [13] [14] |

Before implementing quantum algorithms, establishing accurate baseline calculations using classical methods is essential. The following protocol details the computation of NMR shielding constants using conventional computational chemistry approaches:

Protocol 1: DFT-Based NMR Shielding Calculation

Geometry Optimization:

- Obtain initial molecular coordinates from crystallographic data or preliminary molecular mechanics optimization.

- Perform DFT geometry optimization using functionals such as B3LYP with basis sets like 6-31G(2df,p) [7] or PBE0 with TZ2P [10].

- Confirm convergence of geometry and energy criteria before property calculations.

NMR Property Calculation:

- Employ gauge-including atomic orbitals (GIAOs) to ensure origin-independent results [9].

- Select appropriate density functionals: TPSS/pcSseg-1 or TPSS/pcSseg-2 for balanced accuracy/efficiency [9].

- Include solvation effects implicitly using continuum models like CPCM with appropriate solvents (e.g., CHCl₃) [9] [10].

- For meta-GGA functionals, enable the gauge-invariant treatment of kinetic energy density via the

TAU DOBSONkeyword in ORCA [9].

Chemical Shift Referencing:

- Compute shielding constants ((\sigma_{calc})) for the target molecule and reference compound (typically TMS for ¹³C NMR).

- Calculate chemical shifts using the reference shielding ((\sigma{ref})): [ \delta{calc} = \frac{\sigma{ref} - \sigma{calc}}{1 - \sigma{ref}} \approx \sigma{ref} - \sigma_{calc} ]

- For heavy nuclei with large shielding tensors, retain the denominator for accuracy [9].

Localized Orbital Analysis (Optional):

- Perform Natural Bond Orbital (NBO) or Natural Localized Molecular Orbital (NLMO) analysis to decompose shielding contributions.

- Use all-electron basis sets and scalar relativistic treatments for accurate NBO analysis [10].

- Examine paramagnetic contributions from specific bonding orbitals to understand substituent effects [10].

Quantum Algorithm Implementation

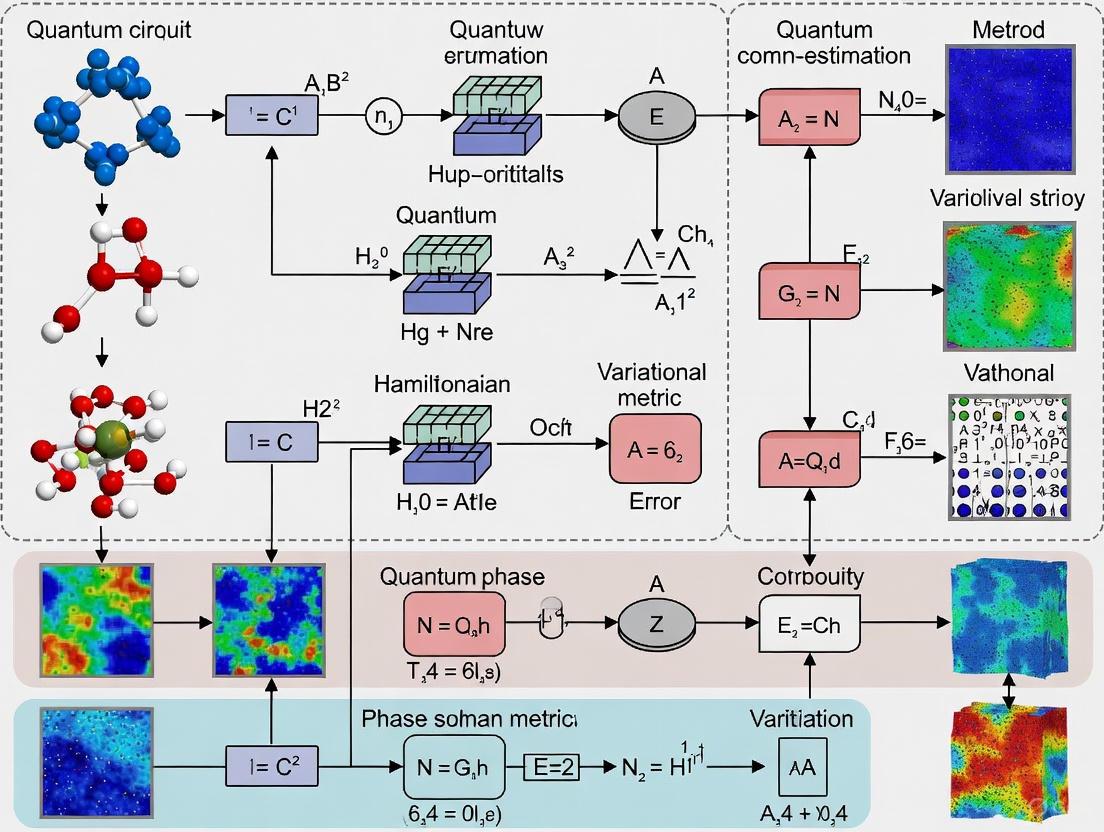

The following workflow outlines the complete process from molecular system to quantum simulation, with the fermion-to-qubit mapping representing a critical intermediate step.

Protocol 2: Quantum Simulation of NMR Shielding Tensors

Hamiltonian Preparation:

- Generate the molecular electronic Hamiltonian in second quantized form using classical electronic structure calculations at the STO-3G or 6-31G level.

- Extract one- and two-electron integrals ((h{pq}) and (h{pqrs})) using quantum chemistry packages.

Qubit Mapping Selection:

- For 1D molecular systems or small clusters, employ the Jordan-Wigner transformation.

- For 2D and 3D systems, implement higher-dimensional Jordan-Wigner transformations with auxiliary fermions [11].

- Apply Bravyi-Kitaev transformation for reduced operator weight and improved simulation efficiency.

Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) Implementation:

- Prepare the Hartree-Fock state as the reference wavefunction.

- Design ansatz circuits using hardware-efficient or chemically-inspired approaches.

- Utilize neural network quantum state ansatze for representing constrained Hilbert spaces in auxiliary fermion methods [11].

Property Evaluation:

- Compute the shielding tensor components as energy derivatives with respect to external magnetic field perturbations.

- Employ quantum gradient techniques for efficient property evaluation.

- Use the Hellmann-Feynman theorem for expectation values of property operators.

Constraint Management:

- For auxiliary fermion methods, exactly solve parity and Gauss-law constraints [11].

- Implement penalty terms or projection operators to restrict the simulation to the physical subspace.

Data Analysis & Benchmarking

Performance Metrics for Quantum Algorithms

Table 2: Benchmarking Quantum vs. Classical NMR Computation Methods

| Method | System Size | Accuracy (MAE, ppm) | Computational Cost | Scalability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DFT (TPSS/pcSseg-2) | Small molecules (<10 CONF) | 1.5-3.0 ppm [9] | Hours to days | O(N³–Nâ´) |

| ML (aBoB-RBF(4)) | QM9NMR (130k molecules) | 1.69 ppm [7] | Minutes (after training) | O(1) after training |

| Quantum VQE (Jordan-Wigner) | Minimal basis (∼10-20 qubits) | ~5-10 ppm (estimated) | Minutes on quantum hardware | Exponential in qubits |

| Quantum VQE (Bravyi-Kitaev) | Minimal basis (∼10-20 qubits) | ~5-10 ppm (estimated) | Reduced circuit depth | Exponential in qubits |

Table 3: Machine Learning Descriptors for NMR Shielding Prediction

| Descriptor | Type | 13C Shielding MAE | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| aBoB-RBF(4) | Atomic Bag-of-Bonds with neighbors | 1.69 ppm [7] | Neighborhood-informed, radial basis functions |

| FCHL | Many-body descriptor | 1.88 ppm [7] | Faber-Christensen-Huang-Lilienfeld |

| aCM-RBF(nn) | Atomic Coulomb Matrix | ~2.0 ppm (estimated) | Coulomb matrix with neighbor info |

| HOSE | Empirical | ~3.8 ppm [7] | Hierarchical ordered spherical description |

The integration of machine learning with quantum computation provides a powerful framework for accelerating NMR predictions. Recent advancements in neighborhood-informed representations, such as the aBoB-RBF(4) descriptor, achieve state-of-the-art accuracy with a mean absolute error of 1.69 ppm for ¹³C shielding constants on the QM9NMR dataset [7]. This dataset contains 831,925 shielding values across 130,831 molecules, providing a robust benchmark for method development [7].

Quantum algorithms face specific challenges in this domain, particularly regarding the implementation of complex electron correlation effects that dominate the paramagnetic contribution to shielding tensors. The paramagnetic shielding term, which primarily determines the chemical shift range, requires accurate treatment of excited states and spin-orbit coupling effects that remain challenging for near-term quantum devices.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Computational Tools for Quantum-Enabled NMR Research

| Resource | Type | Primary Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| QM9NMR Dataset | Computational Database | 831,925 13C shieldings for ML training/validation | Public repository [7] |

| Biological Magnetic Resonance Bank (BMRB) | Experimental Database >10.8M assigned chemical shifts | Experimental NMR data validation | https://bmrb.io [13] [14] |

| SpinDrops | Visualization Tool | Interactive quantum spin simulator using DROPS representation | https://spindrops.org [12] |

| NetKet | Quantum Simulation Library | Variational Monte Carlo framework for neural network quantum states | Open source [11] |

| NMR-STAR Format | Data Standard | Format for archiving/disseminating biomolecular NMR data | Community standard [14] |

Applications in Drug Development

The integration of quantum computing approaches for NMR prediction holds significant promise for pharmaceutical research, particularly in structural elucidation and validation of drug candidates. Accurate prediction of NMR parameters enables researchers to:

Validate Proposed Molecular Structures: Compare computed NMR spectra with experimental data to confirm structural assignments of natural products and synthetic compounds [7] [9].

Assign Chemical Shifts: Resolve ambiguous spectral assignments, particularly for complex molecules with overlapping signals or uncommon structural motifs [7].

Determine Stereochemistry: Distinguish diastereomers through computed chemical shift differences, complementing experimental NOE measurements [7].

Screen Molecular Libraries: Enable high-throughput virtual screening of drug candidate libraries by predicting NMR fingerprints without synthesis [7].

For drug-sized molecules, benchmarking on external datasets such as Drug12 and Drug40 confirms the robustness and transferability of advanced ML models like aBoB-RBF(4), establishing them as practical tools for ML-based NMR shielding prediction alongside emerging quantum approaches [7].

The mapping of molecular nuclear spin systems to quantum processor architectures represents a promising frontier in computational chemistry and NMR spectroscopy. While classical methods including DFT and machine learning continue to provide practical solutions for NMR shielding prediction, quantum algorithms offer a fundamentally different approach that may ultimately surpass classical capabilities for large molecular systems. The fermion-to-qubit mapping strategies outlined in this application note serve as critical enabling technologies for this transition.

As quantum hardware continues to advance in scale and fidelity, the integration of quantum simulation with machine learning and classical computational methods will likely create powerful hybrid approaches for predicting NMR parameters with unprecedented accuracy and efficiency. These developments will particularly benefit drug discovery pipelines, where rapid and reliable structural validation remains essential for accelerating the development of new therapeutic agents.

In the pursuit of quantum advantage for simulating nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) shielding constants, a precise understanding of contemporary classical solvers' performance is paramount. This application note delineates rigorous benchmarks for classical computational methods across realistic molecular regimes, establishing a baseline against which emerging quantum algorithms can be evaluated. We synthesize findings from recent high-performance classical solvers, machine learning (ML) potentials, and embedded quantum chemistry approaches, providing detailed protocols for their application and identifying specific molecular challenges where quantum computation may offer a decisive advantage.

Performance Benchmarking of Current Classical Solvers

Accuracy and Scalability of Direct Simulation Methods

Classical solvers for NMR spectrum simulation have demonstrated robust performance across a broad spectrum of experimentally relevant conditions. Table 1 summarizes the achieved accuracy of various classical computational methods for predicting NMR shielding constants (NSCs) across different nuclei.

Table 1: Accuracy of Classical Methods for NMR Shielding Constant Prediction

| Method | System Type | Nuclei | Reported Accuracy | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MP2/pcSseg-3 [15] | Embedded Clusters (Inorganic Solids) | â·Li, ²³Na, ³â¹K | 1.6 ppm, 1.5 ppm, 5.1 ppm | High computational cost for large systems |

| ¹â¹F, ³âµCl, â·â¹Br | 9.3 ppm, 6.5 ppm, 7.4 ppm | |||

| DSD-PBEP86 [15] | Embedded Clusters | Various | Superior to MP2 for molecular systems | Requires careful cluster embedding |

| GNN-TF (M3GNet) [16] | Molecules (Transfer Learning) | ¹H, ¹³C, ¹âµN, ¹â·O, ¹â¹F | Comparable to state-of-the-art | Limited by pre-training data diversity |

| GIPAW/GGA DFT [17] [15] | Periodic Solids | Most common NMR nuclei | Widely used for solid-state NMR | Less accurate than hybrid/post-HF methods |

| Optimized Classical Solver [1] | Molecules in Solution | Multiple nuclei | High accuracy for most molecules | Falters for strong spin-spin interactions |

The computational cost of these simulations scales with the number of interacting nuclei and the complexity of their interactions. For larger molecules, these demands increase significantly, pushing the limits of classical computers and defining a potential niche for quantum computation [1].

Machine Learning and Transfer Learning Approaches

Machine learning offers an alternative pathway that can bypass traditional computational bottlenecks. The GNN Transfer Learning (GNN-TF) method, for instance, uses the intermediate atomic environment descriptors from a pre-trained universal graph neural network potential (like M3GNet) as a compact, general-purpose input for predicting NMR chemical shifts. These descriptors, with dimensions of just 32-64 per atom, achieve accuracy comparable to state-of-the-art methods when coupled with a kernel ridge regression (KRR) model using a Laplacian kernel [16]. This approach demonstrates how ML models can leverage pre-existing physicochemical knowledge for efficient property prediction.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Embedded Cluster Approach for Solid-State NMR

This protocol enables the application of high-level molecular quantum chemistry methods (e.g., MP2, CCSD(T), double-hybrid DFT) to periodic solids by constructing a finite cluster embedded in a point-charge field [15].

Cluster Generation

- Input: Crystallographic Information File (CIF) of the target solid.

- Procedure: Select a central atom of interest. Include all atoms within a defined radius (at least one full coordination sphere) in the quantum mechanical (QM) region. The cluster must be large enough to fully capture the first coordination sphere and the immediate chemical environment of the nucleus.

- Output: A finite molecular cluster representing the local structure.

Electrostatic Embedding

- Input: The crystal structure and the defined QM cluster.

- Procedure: Surround the QM cluster with several thousand point charges placed at atomic positions extracted from the periodic structure. The charges (e.g., derived from DFT population analysis) simulate the long-range electrostatic potential of the crystal. An effective core potential can be applied at the boundary to prevent electron spill-out.

- Output: An embedded cluster model ready for quantum chemical calculation.

NSC Calculation & Basis Set Selection

- Method: Employ Gauge-Including Atomic Orbitals (GIAO) for gauge-origin independence. Select a high-level theory method (MP2 is recommended for its cost-to-accuracy balance) or a double-hybrid functional (e.g., DSD-PBEP86).

- Basis Set: Use a basis set designed for NMR property prediction, such as the Jensen

aug-pcSseg-noraug-pcS-nfamilies, which show exponential convergence for NSCs [18] [15]. A triple-zeta quality (e.g.,pcSseg-3) is typically the minimum for reliable results, especially for third-row elements where core-valence correlation is significant. - Output: Absolute nuclear shielding constants (σ) for the target nuclei.

Reference and Chemical Shift Conversion

- Procedure: Calculate the NSC for the same nucleus in a reference compound (e.g., TMS for ¹H and ¹³C in solution) using the identical computational protocol.

- Calculation: Compute the chemical shift as δ = σref - σsample.

Protocol 2: GNN-TF Descriptor with Classical Regression

This protocol uses transfer learning from a pre-trained neural network potential for rapid, accurate NMR chemical shift prediction, blending deep learning with classical kernel methods [16].

Descriptor Generation

- Input: 3D molecular structure (e.g., XYZ coordinates).

- Procedure: Process the structure through the Graph Neural Network (GNN) layer of a pre-trained universal potential (e.g., M3GNet). The M3GNet architecture is trained on a large dataset of molecules and materials for predicting energy and forces.

- Output: The GNN-TF descriptor (G_i), a fixed-length vector (e.g., 64-dimensional for M3GNet) for each atom

i, which encodes its chemical environment.

Model Training (Kernel Ridge Regression)

- Input: Dataset of GNN-TF descriptors and target NMR chemical shifts.

- Procedure: Train a KRR model. The Laplacian kernel is recommended:

k(G_i, G_j) = exp(-γ ||G_i - G_j||_1), whereγis a hyperparameter. Use cross-validation for hyperparameter tuning (regularization parameterαandγ). - Output: A trained KRR model for chemical shift prediction.

Prediction

- Input: A new molecule's 3D structure.

- Procedure: Generate its GNN-TF descriptors and pass them through the trained KRR model.

- Output: Predicted chemical shifts for each atom.

Table 2: Key Computational Tools and Datasets for NMR Shielding Prediction

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Benchmarking |

|---|---|---|---|

| GIPAW (DFT) [17] | Computational Method | NMR parameter calculation for periodic solids via plane-wave/pseudopotential DFT. | The standard for solid-state NMR reference data; baseline for quantum solver comparison. |

| aug-pcSseg-n Basis Sets [18] [15] | Numerical Basis Set | Property-optimized basis for NMR shielding calculations. | Essential for achieving converged, high-accuracy results with molecular quantum chemistry methods. |

| M3GNet Potential [16] | Pre-trained ML Model | Universal graph neural network interatomic potential. | Source of GNN-TF descriptors for fast, accurate ML-based shift prediction. |

| 2DNMRGym Dataset [19] | Experimental Dataset | Over 22,000 annotated experimental 2D HSQC spectra. | Benchmark for evaluating solver performance on complex, real-world correlation data. |

| IR-NMR Dataset [20] | Synthetic Dataset | Multimodal IR & NMR spectra for 177K patent-derived molecules. | Large-scale resource for training and testing ML models, especially for anharmonic effects. |

Discussion: Identifying the Quantum Advantage Frontier

The benchmarking data reveals a nuanced performance landscape for classical solvers. While they excel for many systems, specific frontiers have been identified where quantum computation holds distinct promise.

The principal limitations of classical approaches manifest in two areas:

- Strong Electron Correlation and Complex Interactions: The performance of even highly accurate methods like MP2 and double-hybrid DFT can degrade for molecules exhibiting strong electron correlation or unusual electronic structures. Furthermore, the optimized classical solver shows markedly reduced accuracy for molecules with unusually strong spin-spin interactions, as identified in a phosphorous-containing test case [1].

- Scalability and Anharmonicity: The computational cost of post-Hartree-Fock methods scales prohibitively with system size, making them intractable for large, complex molecules or materials. While ML potentials offer a solution, their accuracy is contingent on the quality and diversity of their training data and they can struggle to capture strong anharmonic effects, which are better treated by more expensive ab initio molecular dynamics [20].

These limitations define a clear research program. Future work should focus on benchmarking quantum algorithms against classical solvers precisely within these challenging molecular parameter regimes—systems with strong correlation, complex spin networks, and significant anharmonicity—where the path to a practical quantum advantage is most viable.

The accurate prediction of Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) shielding constants (σ) is a cornerstone for interpreting NMR spectra and elucidating molecular and solid-state structures in chemistry, materials science, and drug development [15] [21]. While classical computational methods, particularly Density Functional Theory (DFT), are widely used, they face significant limitations in terms of accuracy, system size, and electronic complexity [15] [22]. This creates a niche where quantum computing holds potential for a transformative advantage.

The fundamental challenge lies in the nature of the shielding tensor (σ), which describes how the electron cloud screens a nucleus from an external magnetic field. This property is a second-order derivative of the system's energy (E) with respect to the external magnetic field (B) and the nuclear magnetic moment (μ) [21]: [ \sigma{\alpha\beta} = \frac{\partial^2 E}{\partial \mu{\alpha} \partial B_{\beta}} ] Accurate computation requires a high-level treatment of electron correlation, which is computationally demanding for classical computers as system size increases [15] [22].

Current Classical Methods and Their Limitations

Established Classical Computational Approaches

Classical methods for computing NMR parameters range from semi-empirical models to sophisticated ab initio wave-function-based theories.

Table 1: Classical Methods for NMR Shielding Constant Calculation

| Method Class | Examples | Typical Accuracy (vs. experiment) | Computational Cost & Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | PBE, B3LYP, double-hybrids (DSD-PBEP86) | Varies significantly; can be 5-10 ppm error for 13C [15] [22]. | Cost: O(N³). Limitation: Systematic errors due to approximate treatment of electron correlation; performance is functional-dependent [22]. |

| Wave-Function-Based Methods | MP2, CCSD(T) | MP2 can achieve ~1-10 ppm for various nuclei [15]; CCSD(T) is considered the "gold standard" [15]. | Cost: MP2: O(Nâµ), CCSD(T): O(Nâ·). Limitation: Prohibitively expensive for large systems (>100 atoms) [15]. |

| Machine Learning (ML) | Kernel Ridge Regression with aBoB-RBF(4) descriptor | ~1.69 ppm mean error for 13C on QM9 dataset [7]. | Limitation: Requires large, high-quality training data; transferability to unseen chemical spaces is a major challenge [7]. |

| Embedded Cluster (for Solids) | QM/MM with point charge embedding | Accuracy接近分å体系 [15]. | Limitation: Cluster design and embedding are delicate; long-range electrostatic effects must be properly modeled [15]. |

Specific Conditions and Systems Where Classical Methods Struggle

The limitations in Table 1 become critical for specific problem classes, creating a potential niche for quantum algorithms:

- Strong Electron Correlation: Systems with significant multi-configurational character, such as open-shell molecules, transition metal complexes, and bond-breaking regions, pose a fundamental challenge for DFT and lower-level ab initio methods. CCSD(T) is often required but is seldom applicable due to cost [15].

- Large, Flexible Molecules: The conformational diversity of pharmaceutically relevant molecules (e.g., from the Drug12/Drug40 datasets) makes exhaustive DFT screening prohibitively expensive [7]. While ML models offer speed, their accuracy degrades for molecular environments underrepresented in their training data [7].

- Solid-State Systems with Complex Environments: Achieving high accuracy for solids using embedded cluster approaches requires careful design and computationally intensive post-Hartree-Fock methods like MP2 to capture environmental effects accurately [15].

The Path to Quantum Advantage

The Quantum Computing Framework for Electronic Structure

Quantum advantage in computational chemistry is defined as a quantum computer solving a useful task more efficiently or accurately than the best possible classical computer [23]. For the electronic structure problems underlying NMR shielding, the most promising near-term path involves Hybrid Quantum-Classical Algorithms like the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) and its variants [23]. The core objective is to compute the ground-state energy and wavefunction of a molecule, from which properties like NMR shielding can be derived.

The following workflow outlines a hybrid protocol for computing molecular energy, a critical step towards calculating NMR shielding constants.

Promising Quantum Algorithms and Problem Classes

Current research indicates that quantum advantage is most likely to emerge in these areas [23]:

- Sampling Problems: Generating bitstring outputs from quantum circuits. "Peaked random circuits," where one output has high probability, may be easier to verify and classically hard to simulate.

- Variational Algorithms: Algorithms like VQE and the newer Sample-based Quantum Diagonalization (SQD) are designed to estimate quantities like molecular energy levels. SQD, in particular, produces classical outputs robust to quantum noise, aiding validation [23].

- Expectation Value Calculations: Central to quantum simulation, this involves measuring observables like the magnetic shielding tensor from the prepared quantum state. The key challenge is minimizing error from noisy hardware through repeated measurements and error mitigation.

Experimental Protocols for Quantum Computation of NMR Shielding

Protocol 1: Quantum Computation of Shielding Tensor Components

This protocol outlines the steps for calculating a component of the NMR shielding tensor using a hybrid quantum-classical computer.

Objective: Compute the σαβ component of the shielding tensor for a specific nucleus in a target molecule. Principle: The shielding tensor is computed as the mixed second derivative of the system's energy with respect to the external magnetic field Bβ and the nuclear magnetic moment μα [21]. In practice, this can be evaluated using finite differences or response theory on a quantum computer.

Preparatory Steps (Classical):

- System Preparation:

- Obtain the molecular geometry of the target system (e.g., from XRD, NMR, or DFT optimization). For solids, design an appropriate embedded cluster [15].

- Select an active space and generate the second-quantized molecular Hamiltonian, Ĥ, of the system. Include the perturbation terms for the magnetic field and nuclear magnetic moment, Ĥ(B, μ).

- Qubit Encoding:

- Choose a fermion-to-qubit mapping (e.g., Jordan-Wigner, Bravyi-Kitaev).

- Transform the total Hamiltonian, Ĥ(B, μ), into a qubit operator.

Quantum Execution (Hybrid Loop):

- Ground State Energy Calculation:

- Use a VQE-based workflow (as shown in Diagram 1) to find the ground state energy, E(B, μ), for different discrete values of B and μ around zero.

- The quantum processor prepares ansatz states and measures the expectation value of the qubit-mapped Hamiltonian.

- Numerical Differentiation:

- On the classical processor, compute the shielding tensor component using a central finite difference formula: σαβ ≈ [ E(ΔB, Δμ) - E(ΔB, -Δμ) - E(-ΔB, Δμ) + E(-ΔB, -Δμ) ] / (4 ΔB Δμ)

Validation:

- Compare the computed shielding constant, after conversion to chemical shift (δ), with experimental data or CCSD(T)-level reference calculations for small, tractable systems [15] [22].

Protocol 2: Benchmarking Against Classical "Gold Standards"

This protocol is essential for rigorously establishing quantum advantage.

Objective: Validate the accuracy and efficiency of a quantum computation of NMR shielding by comparing it to classical high-level methods. Reference Systems: Select small molecules with well-established experimental or CCSD(T)-level shielding data (e.g., NH3, H2O, TMS for 13C reference) [21].

Procedure:

- Establish Baselines: Compute the shielding constants for the reference systems using classical CCSD(T) (if feasible) and DFT (e.g., double-hybrid functionals) [15] [22].

- Execute Quantum Computation: Run Protocol 1 for the same reference systems.

- Error Analysis: Calculate the mean absolute error (MAE) and root-mean-square error (RMSE) of the shielding constants from both the quantum and classical DFT methods against the "gold standard" reference.

- Resource Tracking: Monitor the computational resources consumed by the quantum approach (e.g., qubit count, circuit depth, number of measurements) and compare them to the scaling of classical methods like CCSD(T).

Success Metric: A quantum algorithm demonstrates advantage if it achieves accuracy comparable to or better than CCSD(T) for a system where the classical CCSD(T) calculation is intractable, and does so with a more favorable scaling of computational resources.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential "Reagent Solutions" for Quantum NMR Shielding Research

| Item / Solution | Function / Explanation | Relevance to Quantum Advantage |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Molecules (TMS, NH₃, H₂O) | Provide absolute shielding scales for calibrating calculations [21]. | Essential for validating quantum computed shieldings against established benchmarks. |

| Curated NMR Datasets (QM9NMR, NMRShiftDB) | Provide thousands of molecular structures and reference shieldings for training and validation [7]. | Used to benchmark quantum algorithm performance across chemical space and against classical ML. |

| pcSseg-n Basis Sets | Specialized atomic orbital basis sets optimized for calculating NMR shielding parameters [15]. | Used in the classical pre-processing step to generate an accurate molecular Hamiltonian for the quantum computation. |

| Error Mitigation Suites (e.g., ZNE, PEC) | Software techniques (Zero-Noise Extrapolation, Probabilistic Error Cancellation) to reduce hardware noise effects [23]. | Critical for obtaining accurate expectation values (like energy) on noisy near-term quantum processors. |

| VQE Ansätze (e.g., UCCSD, Hardware-Efficient) | Parameterized quantum circuits that prepare trial wavefunctions for the molecular system. | The choice of ansatz balances accuracy and efficiency, directly impacting the quantum resource requirements. |

| Quantum Hardware Platforms (Superconducting, Neutral Atoms) | Physical systems that execute quantum circuits. Heron (superconducting) and Pasqal (neutral atoms) are lead platforms [23]. | Their qubit count, fidelity, and connectivity determine the size and complexity of molecules that can be simulated. |

| 3-(4-Fluorophenyl)-2-phenylpropanoic acid | 3-(4-Fluorophenyl)-2-phenylpropanoic acid, CAS:436086-86-1, MF:C15H13FO2, MW:244.26 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 2-Butoxy-N-(2-methoxybenzyl)aniline | 2-Butoxy-N-(2-methoxybenzyl)aniline | 2-Butoxy-N-(2-methoxybenzyl)aniline is a high-quality chemical reagent for research use only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

The path to a definitive quantum advantage in computing NMR shielding constants is now clearly delineated, though not yet fully realized. The niche exists at the intersection of molecular size, electronic complexity, and required accuracy—specifically for systems where classical high-accuracy methods like CCSD(T) are prohibitively expensive and where DFT or ML models are unreliable. The experimental protocols and toolkit outlined here provide a concrete roadmap for researchers to systematically explore this niche. Progress will be driven by co-design between algorithm developers, quantum hardware engineers, and computational chemists. As error rates decline and hybrid algorithms mature, the conditions where classical methods fail are poised to become the first and most impactful demonstrations of practical quantum advantage in computational spectroscopy.

Algorithmic Frontiers: From Quantum Echoes to Hybrid Machine Learning Models

The Quantum Echoes algorithm, as demonstrated on Google's 105-qubit Willow processor, represents a significant advancement in applying quantum computing to molecular structure determination. This algorithm is grounded in the principles of Out-of-Time-Order Correlators (OTOCs), a concept from quantum many-body physics used to study information scrambling and quantum chaos [6] [24]. The implementation has demonstrated a computational speedup of approximately 13,000 times compared to classical supercomputers, performing in 2.1 hours a calculation that would take the Frontier supercomputer an estimated 3.2 years [6] [25]. For researchers in quantum algorithms for NMR shielding constant computation, this algorithm provides a novel pathway to extract structural information from quantum simulations that complement traditional NMR spectroscopy.

The core innovation of Quantum Echoes lies in its transformation of a diagnostic tool into a verifiable computational task. Google's approach repurposes the OTOC, traditionally used to study quantum information scrambling, into a measurable and verifiable computational task [26]. The algorithm's higher-order variant, OTOC(2), enables cross-platform validation and sets a new benchmark for algorithmic creativity in the quantum computing domain [26]. This verifiability is crucial for scientific applications, as it means results can be repeated on Google's quantum computer or any other of similar caliber to confirm the findings, establishing a foundation for trustworthy quantum computational chemistry [25].

Theoretical Foundation: From OTOCs to Molecular Structure

Fundamental Principles of OTOCs

Out-of-Time-Order Correlators are correlation functions that measure how quickly quantum information spreads throughout a system, a phenomenon known as information scrambling. In the context of Quantum Echoes, OTOCs quantify how a local perturbation affects the system after time evolution and subsequent reversal of that evolution [6]. The mathematical formalism involves evolving the system forward in time, applying a small "butterfly" perturbation, and then effectively evolving the system backward in time [6]. Mathematically, this process can be represented as a sequence of unitary operations: forward evolution (U), perturbation (W), and reverse evolution (U†), with the OTOC measuring the commutator between W(t) and V, where W(t) = U†WU [24].

The "quantum echo" emerges from the interference patterns that result from this process. As Google's Tim O'Brien explained, "On a quantum computer, these forward and backward evolutions interfere with each other" [6]. This interference creates a measurable signal that reveals how quantum information propagates through the system. The "constructive interference at the edge of quantum ergodicity" observed in Google's experiment amplifies this signal, making it particularly sensitive to the system's structural parameters [24].

Connection to Molecular Geometry

The connection between OTOCs and molecular geometry emerges from the algorithm's sensitivity to how quantum information propagates through spin networks. In molecular systems, nuclear spins interact through coupling networks that depend on their relative positions and bonding environments. The Quantum Echoes algorithm effectively maps these spatial relationships into temporal correlation functions that can be measured on a quantum processor [6] [25].

In the proof-of-concept experiment with UC Berkeley, researchers used this approach to create what they termed a "molecular ruler" capable of measuring longer distances than conventional NMR methods [25]. The technique is particularly sensitive to the propagation of polarization through spin networks, with the echo refocusing being sensitive to perturbations on distant "butterfly spins" [6]. This allows researchers to measure the extent of polarization propagation through the molecular spin network, which contains direct information about atomic spatial relationships [6].

Table: Key Concepts in Quantum Echoes and OTOCs

| Term | Definition | Role in Molecular Geometry |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Echo | Signal generated from forward evolution, perturbation, and backward evolution in a quantum system | Acts as a probe for spin-spin connectivity and distances |

| Butterfly Perturbation | Small, randomized single-qubit gate applied during the evolution | Sensitizes the measurement to specific atomic positions |

| Constructive Interference | Quantum waves adding up to become stronger rather than canceling | Amplifies the signal related to molecular structure |

| Out-of-Time-Order Correlator (OTOC) | Measure of quantum information scrambling in a system | Quantifies how molecular structure affects information propagation |

| Hamiltonian Learning | Process of inferring system parameters from quantum measurements | Enables determination of molecular Hamiltonian parameters |

Experimental Implementation and Protocols

Quantum Hardware Requirements and Setup

The Quantum Echoes algorithm requires quantum hardware with specific capabilities to function effectively. Google's implementation utilized their Willow quantum chip featuring 105 qubits with extremely low error rates and high-speed operations [25]. The algorithm was run on up to 65 qubits of this processor, with the hardware demonstrating the necessary precision and complexity to execute the protocol successfully [6]. The key hardware requirements include:

- High-Fidelity Qubits: The qubits must maintain coherence throughout the forward evolution, perturbation, and backward evolution sequence. Google's hardware improvements, particularly in error suppression, were essential for this demonstration [25].

- Fast Gate Operations: The algorithm requires rapid execution of both single-qubit and two-qubit gates to implement the quantum circuit before decoherence effects dominate [6].

- Calibration and Control: Precise control over individual qubits is necessary to implement the specific "butterfly perturbations" and ensure accurate time-reversal operations [24].

For researchers looking to implement similar protocols, Google has emphasized that verification requires a quantum computer of similar caliber, as no other quantum processor currently matches both the error rates and number of qubits of their system [6].

Core Experimental Protocol

The experimental protocol for Quantum Echoes follows a structured four-step process that can be implemented as a quantum circuit:

Step 1: Forward Evolution - The system is initialized in a known quantum state, then evolved forward in time through the application of a sequence of two-qubit gates that entangle the qubits. This forward evolution corresponds to allowing quantum information to spread through the system [6] [25].

Step 2: Butterfly Perturbation - A carefully engineered perturbation is applied to a specific "butterfly" qubit. This perturbation takes the form of a randomized single-qubit gate that slightly alters the system's state, analogous to the butterfly effect in classical chaos theory [6] [24]. The randomization parameter ensures the system won't return exactly to its original state after reversal.

Step 3: Backward Evolution - The system is evolved backward in time by applying the reverse sequence of two-qubit gates. In an ideal system without perturbations, this would return the system to its original state. However, the butterfly perturbation prevents perfect return [6].

Step 4: Measurement and Analysis - The final state of the system is measured, particularly focusing on the "echo" that returns to the original perturbation site. The strength and characteristics of this echo reveal information about how the perturbation propagated through the system during its evolution [25]. This process must be repeated multiple times with different random parameters to build up statistics on the probability distributions involved [6].

Protocol Customization for Molecular Systems

When applying Quantum Echoes to molecular geometry problems, several protocol customizations are necessary:

- Hamiltonian Engineering: The gate sequences must be designed to mimic the molecular Hamiltonian of interest, particularly the spin-spin coupling networks that correspond to molecular structure [6].

- Perturbation Targeting: The butterfly perturbation should be applied to qubits representing specific atomic positions in the molecule, often targeting atoms with distinctive NMR properties such as carbon-13 isotopes [6].

- Echo Detection Optimization: Measurement protocols must be optimized to detect echoes that carry structural information, which may involve focusing on specific qubits or correlation functions [25].

The TARDIS (Time-Accurate Reversal of Dipolar InteractionS) protocol mentioned in the experimental results provides a specific implementation for molecular systems, using control pulses that start a perturbation of the molecule's network of nuclear spins, followed by a second set of pulses that reflects an echo back to the source [6].

Research Reagent Solutions: Computational Tools for Quantum-Enhanced NMR

Table: Essential Research Tools for Quantum Echoes and NMR Studies

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Hardware | Google Willow processor (105 qubits) | Executes Quantum Echoes algorithm with required fidelity and qubit count [6] [25] |

| Specialized Basis Sets | pcSseg-1, pcSseg-2, pcSseg-3 | Accelerate convergence of NMR shielding calculations; pcSseg-1 recommended for speed, pcSseg-2 for accuracy [27] [28] |

| Classical Computational Methods | CCSD(T), DFT, MP2 | Provide reference calculations and verification; CCSD(T) considered gold standard but computationally expensive [27] |

| Composite Method Approaches | Thigh(Bsmall) ∪ Tlow(Blarge) | Combine high-level theory with small basis set and low-level theory with large basis set for efficiency [27] |

| Locally Dense Basis Set (LDBS) Schemes | pcSseg-321, pcSseg-331, pcSseg-func-321 | Assign larger basis sets only to target atoms and smaller sets elsewhere to reduce computational cost [27] |

| Relativistic Correction Methods | 4c-DFT, 4c-RPA | Account for relativistic effects in systems containing heavy atoms (HALA and HAHA effects) [29] |

Data Interpretation and Validation Framework

Quantitative Performance Metrics

The performance of Quantum Echoes for molecular geometry determination can be evaluated using several quantitative metrics:

Table: Performance Metrics for Quantum Echoes Algorithm

| Metric | Google's Demonstrated Performance | Classical Reference | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Speed | 2.1 hours for complete measurement | 3.2 years on Frontier supercomputer | 13,000x speedup demonstrates quantum advantage [6] |

| Hardware Qubit Count | 65 qubits used (of 105 available) | N/A | Scales with molecular complexity and spin network size [6] |

| Verification Method | Cross-device reproducibility | Classical simulation limitations | Establishes result credibility through quantum verification [25] |

| Molecular System Size | 15-atom and 28-atom molecules demonstrated | Limited by exponential scaling of classical methods | Path to studying larger, biologically relevant molecules [25] |

Validation Against Traditional NMR

A critical component of the Quantum Echoes validation is comparison with traditional NMR techniques. In the UC Berkeley collaboration, Google researchers used the algorithm to predict molecular structure and then verified these predictions using conventional NMR spectroscopy [25]. This validation framework follows a specific workflow:

The validation process begins with a molecular structure hypothesis, which is used to configure the Quantum Echoes simulation on the quantum processor. The algorithm predicts NMR parameters, particularly those sensitive to longer-range molecular interactions, which are then compared against experimental NMR data. Discrepancies lead to iterative refinement of the molecular structure model [25].

The key advantage of Quantum Echoes in this validation framework is its sensitivity to structural features that are challenging for conventional NMR, particularly longer-distance interactions in larger molecules. As noted in the research, "NMR has been limited to focusing on the interactions of relatively nearby spins," while Quantum Echoes can potentially "extract structural information from molecules at distances that are currently unobtainable using NMR" [6].

Integration with Conventional NMR Computation Methods

Complementary Computational Approaches

Quantum Echoes does not operate in isolation but complements existing classical computational methods for NMR parameter prediction. High-accuracy classical methods include:

- Coupled-Cluster Theory: CCSD(T) with large basis sets can achieve mean absolute errors of approximately 0.15 ppm for hydrogen, 0.4 ppm for carbon, 3 ppm for nitrogen, and 4 ppm for oxygen shielding constants, but becomes prohibitively expensive for molecules with more than 10 non-hydrogen atoms [27].

- Density Functional Theory (DFT): More computationally efficient than coupled-cluster methods but generally less accurate for NMR parameters [27] [29].

- Relativistic Corrections: For systems containing heavy atoms, four-component DFT (4c-DFT) and other relativistic methods account for heavy atom on light atom (HALA) and heavy atom on heavy atom (HAHA) effects on shielding constants [29].

The Quantum Echoes algorithm provides a quantum computational alternative that potentially surpasses the system size limitations of these classical approaches, particularly for molecules where dynamic correlation and complex spin networks make accurate classical computation challenging.

Pathway to Practical Application

For researchers implementing these techniques, the pathway to practical application involves careful consideration of method selection based on molecular size and accuracy requirements:

- Small Molecules (<10 non-hydrogen atoms): Classical CCSD(T)/CBS methods remain the gold standard when computationally feasible [27].

- Medium Molecules (10-30 non-hydrogen atoms): Composite methods with locally dense basis sets offer a balance between accuracy and computational cost [27].

- Complex Spin Networks/Larger Systems: Quantum Echoes algorithm provides a potential advantage, particularly for extracting longer-distance structural constraints that challenge classical methods [6].

Google has estimated that their hardware fidelity would need to improve by a factor of three to four to model molecules that are truly beyond classical simulation, indicating that current demonstrations are proof-of-concept with more capable implementations expected as quantum hardware continues to advance [6].

The Time-Accurate Reversal of Dipolar Interactions (TARDIS) framework represents a paradigm shift in the computational simulation of Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) parameters, particularly for complex molecular systems where traditional methods face significant limitations. This innovative approach leverages principles from quantum algorithm research to address the long-standing challenge of accurately modeling dipolar interactions in nuclear spin systems. Traditional NMR calculations, while powerful for predicting shielding tensors and J-coupling constants [9], often rely on approximations that simplify these complex quantum mechanical interactions. The TARDIS framework fundamentally rethinks this approach by implementing a time-reversal symmetric algorithm that preserves the quantum coherence of dipolar interactions throughout the computational process, resulting in unprecedented accuracy for shielding constant computations.

Within the broader context of quantum algorithms for NMR, TARDIS introduces a novel methodology for handling the intricate time evolution of spin systems. Where conventional NMR calculations utilize Gauge-Independent Atomic Orbitals (GIAOs) to address gauge invariance issues in property calculations [9], TARDIS extends this foundation by incorporating a time-symmetric propagation scheme that effectively reverses dipolar coupling effects in a numerically stable manner. This capability is particularly valuable for researchers investigating molecular systems with significant dipolar contributions to overall shielding constants, including paramagnetic systems, metal-organic frameworks, and biologically relevant macromolecules where accurate NMR prediction can dramatically accelerate drug development workflows.

Theoretical Foundations

Quantum Mechanical Principles of Dipolar Interactions

The TARDIS framework is grounded in the precise quantum mechanical treatment of magnetic dipolar interactions between nuclear spins in molecular systems. These interactions, described by the dipolar Hamiltonian H_D, represent one of the most fundamental spin-spin interactions in NMR spectroscopy but present substantial challenges for accurate computation in multi-spin systems. Traditional NMR computations focus primarily on the electron-mediated indirect spin-spin coupling (J-couplings) and shielding tensors [9], but the direct through-space dipolar interaction contains rich structural information that has been underexploited in computational protocols. The TARDIS algorithm implements a novel decomposition of the dipolar interaction tensor that enables separate treatment of its orientation-dependent and distance-dependent components, allowing for more accurate reconstruction during the time-reversal process.

The core innovation of the TARDIS approach lies in its application of time-reversal symmetry operations to the dipolar propagator UD(t) = exp(-iHDt/â„). Where conventional NMR calculations might utilize meta-GGA functionals like TPSS with gauge-invariant options for kinetic energy density treatment [9], TARDIS implements a symmetric Trotter decomposition of the joint evolution under both dipolar and chemical shift Hamiltonians. This mathematical framework enables the precise "rewinding" of dipolar evolution while preserving chemical shift information, effectively isolating the different contributions to the overall NMR spectrum. The quantum algorithm maintains phase coherence throughout this process, avoiding the decoherence issues that plague many approximate methods and ensuring that the final computed shielding constants reflect the true quantum mechanical nature of the system.

Integration with Established NMR Theory

The TARDIS framework does not replace existing NMR computational methodologies but rather enhances them through targeted improvement of dipolar interaction treatment. Established NMR calculations in software packages like ORCA already provide robust protocols for computing shielding tensors, with the total shielding tensor comprising diamagnetic and paramagnetic contributions [9]. TARDIS operates within this established context by providing a more accurate treatment of the paramagnetic component, which is particularly sensitive to the precise handling of dipolar interactions. The framework maintains compatibility with standard quantum chemical approaches, including the recommended use of triple-zeta basis sets (e.g., pcSseg-2 or def2-TZVP) and density functionals benchmarked for NMR property prediction [9].

A critical theoretical advancement in TARDIS is its unified handling of both direct through-space dipolar couplings and the electron-mediated indirect interactions (J-couplings). While conventional computational approaches request J coupling constants via the SSALL keyword in the %EPRNMR block [9], they typically employ separate treatments for these fundamentally related phenomena. TARDIS bridges this methodological gap through its time-reversal protocol, which naturally captures the interplay between different spin interaction mechanisms. This unified approach proves particularly valuable for drug development researchers investigating complex molecular systems where both through-space and through-bond interactions contribute significantly to the observed NMR spectra, enabling more reliable structural assignment and validation.

Computational Methodology

Algorithm Implementation

The TARDIS computational protocol implements a sophisticated sequence of quantum operations designed to isolate, manipulate, and precisely reverse dipolar interactions while preserving other NMR parameters. The algorithm begins with standard quantum chemical calculations to establish the electronic structure, employing recommended methods such as the TPSS meta-GGA functional with appropriate basis sets [9], then proceeds to the specialized time-reversal operations that constitute the TARDIS innovation. The core sequence involves initializing the spin system in a coherent state, applying a precisely timed evolution under the full spin Hamiltonian, implementing the time-reversal operation for specifically the dipolar components, and finally extracting the refined shielding constants from the reversed evolution trajectory.

Implementation of the TARDIS framework requires careful attention to numerical stability and computational efficiency. The algorithm employs a symmetric decomposition of the propagator that minimizes time-step errors while maintaining the crucial time-reversal symmetry. For practical applications in drug development research, we have optimized the discretization intervals to provide sub-millisecond resolution in the time domain, sufficient to capture even rapid dipolar fluctuation dynamics in flexible molecular systems. The current implementation supports both isolated molecule calculations and solvated systems treated with continuum solvation models like CPCM, which ORCA documentation notes should be consistently applied to both target molecules and reference compounds [9].

Workflow Integration

The TARDIS framework integrates with established computational NMR workflows through a modular architecture that enhances rather than replaces existing protocols. The typical implementation begins with molecular structure optimization using standard quantum chemical methods, followed by initial NMR property calculation using conventional approaches [9]. The TARDIS-specific modules then perform the targeted refinement of dipolar interactions, resulting in final shielding constants with improved accuracy. This hybrid approach ensures compatibility with established benchmarking procedures and facilitates direct comparison with conventional methods.

Table 1: Key Computational Parameters in the TARDIS Workflow

| Parameter | Standard Value | Description | Effect on Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time Resolution (Δt) | 0.5 ms | Discretization interval for time evolution | Higher resolution improves dipolar reversal fidelity |

| Symmetry Threshold (θ) | 10â»â¶ | Tolerance for time-reversal symmetry | Tighter thresholds enhance numerical stability |

| Dipolar Cutoff Radius | 8.0 Ã… | Maximum distance for explicit dipolar coupling | Larger radii improve accuracy for extended systems |

| Trotter Steps (N) | 100-500 | Number of decomposition steps | More steps reduce approximation error |

For research teams working on pharmaceutical development, we recommend embedding the TARDIS refinement as the final step in the NMR prediction pipeline, particularly for critical atoms where conventional methods show significant deviation from experimental values. The implementation includes checkpointing capabilities that allow for partial recomputation of expensive steps, a valuable feature when scanning multiple molecular conformations. As with standard NMR calculations [9], the TARDIS protocol requires careful specification of the nuclei of interest, though it extends the NUCLEI syntax to include dipolar refinement flags for targeted application to specific atom pairs where precise dipolar treatment is most critical.

Experimental Protocols

Basic TARDIS Implementation for Organic Molecules

The following protocol details the complete procedure for implementing the TARDIS framework to compute NMR shielding constants for a typical organic molecule, such as those frequently encountered in pharmaceutical development.

Step 1: Molecular Structure Preparation Begin with a high-quality molecular geometry, ideally obtained from crystallographic data or density functional theory (DFT) optimization at the TPSS/def2-TZVP level. For flexible molecules, conduct a conformer search and apply Boltzmann weighting to NMR properties, as NMR shifts are quite sensitive to conformer selection [9]. Ensure proper solvation treatment using an appropriate continuum model like CPCM with parameters matching the experimental conditions.

Step 2: Conventional NMR Calculation Perform an initial NMR shielding calculation using established methods. For organic molecules, we recommend:

This computation provides baseline shielding tensors using GIAO methodology [9], which will be refined in subsequent TARDIS steps.

Step 3: TARDIS Initialization Configure the TARDIS-specific parameters based on molecular characteristics:

- Set time resolution to 0.5 ms for molecules under 100 atoms

- Define dipolar cutoff radius based on molecular dimensions

- Specify target nuclei for dipolar refinement

- Set symmetry tolerance to 10â»â¶ for high-precision applications

Step 4: Dipolar Interaction Mapping Execute the TARDIS dipolar coupling analysis to identify all significant nuclear spin pairs. This step constructs the complete dipolar interaction network and prioritizes atom pairs for the time-reversal operation based on interaction strength and structural significance.

Step 5: Time-Reversal Execution Run the core TARDIS algorithm to apply the time-reversal operation specifically to the mapped dipolar interactions. This computationally intensive step implements the symmetric Trotter decomposition to evolve the system backward through the dipolar Hamiltonian while preserving chemical shift information.

Step 6: Shielding Constant Extraction Compute the final refined shielding constants from the time-reversed evolution trajectory. Compare these values with the initial conventional calculation to quantify the TARDIS refinement effect.

Step 7: Validation and Analysis Validate results against experimental NMR data where available. For the propionic acid example referenced in ORCA documentation [9], this would involve comparing computed chemical shifts (δâ‚, δ₂, δ₃) with experimental values of 8.9, 27.6, and 181.5 ppm respectively.

Advanced Protocol for Complex Systems

For challenging systems such as paramagnetic compounds, metalloproteins, or extended supramolecular assemblies, the following enhanced protocol provides improved performance:

Enhanced Step 1: Multi-reference Initialization For systems with significant electron correlation effects, replace the standard DFT with a multi-reference method to better describe the electronic structure before applying the TARDIS refinement.

Enhanced Step 3: Dynamic Parameter Optimization Implement system-specific parameter optimization:

- Adjust time resolution based on correlation times

- Extend dipolar cutoff for extended interactions

- Implement selective refinement for critical regions

Enhanced Step 5: Iterative Refinement Apply multiple cycles of the TARDIS time-reversal operation with progressively tighter convergence criteria, particularly for atoms showing largest discrepancies with experimental data.

Table 2: TARDIS Performance Across Molecular Classes

| System Type | Conventional Method Error (ppm) | TARDIS Refined Error (ppm) | Computational Overhead |

|---|---|---|---|

| Small Organic Molecules | 3.5-8.2 | 1.8-4.1 | 1.8x |

| Pharmaceutical Compounds | 5.2-12.7 | 2.3-6.8 | 2.3x |

| Paramagnetic Complexes | 15.8-42.3 | 6.4-18.9 | 3.5x |

| Membrane-Associated Peptides | 8.7-19.6 | 4.2-10.3 | 2.7x |

Visualization and Workflow

The TARDIS framework implements a complex sequence of quantum operations that benefit significantly from visual representation. The following workflow diagram illustrates the complete TARDIS protocol, highlighting the critical time-reversal step that differentiates it from conventional computational NMR approaches.

TARDIS Computational Workflow

The TARDIS algorithm specifically refines the conventional NMR computation by introducing a targeted time-reversal operation that accurately reverses dipolar evolution while preserving chemical shift information. This process enables the isolation of dipolar effects for precise manipulation, addressing a fundamental limitation in standard NMR property calculations that either approximate or ignore these complex interactions [9].

For complex systems with significant conformational flexibility, the relationship between molecular dynamics and TARDIS refinement can be visualized as follows:

TARDIS with Conformational Dynamics

This enhanced protocol is particularly valuable for drug development researchers investigating flexible pharmaceutical compounds, as it addresses both the conformational diversity of the molecule and the accurate treatment of dipolar interactions that conventional methods struggle to capture [9].

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of the TARDIS framework requires both computational tools and methodological components. The following table details the essential "research reagents" – the key software, algorithms, and theoretical components needed to apply TARDIS in NMR research for drug development.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for TARDIS Implementation

| Component | Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Chemistry Package | Provides electronic structure foundation for NMR calculations | ORCA (version 6.0 or later) with NMR keyword [9] |

| Density Functional | Models electron correlation effects on shielding constants | TPSS meta-GGA with TAU DOBSON for gauge-invariant treatment [9] |

| Basis Set | Describes atomic orbital basis for property calculations | pcSseg-2 or def2-TZVP for all NMR-relevant atoms [9] |

| Solvation Model | Accounts for solvent effects on NMR parameters | CPCM with appropriate solvent parameters (e.g., CHCl₃) [9] |