Quantum Error Mitigation Protocols for Near-Term Chemistry Simulations: A Comprehensive Guide

This article provides a comprehensive overview of quantum error mitigation (QEM) protocols essential for performing reliable quantum chemistry simulations on today's noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices.

Quantum Error Mitigation Protocols for Near-Term Chemistry Simulations: A Comprehensive Guide

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of quantum error mitigation (QEM) protocols essential for performing reliable quantum chemistry simulations on today's noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and professionals in drug development, we explore the foundational principles of QEM, detail cutting-edge methodologies like probabilistic error cancellation and Clifford data regression, and present optimization strategies to enhance their efficacy. Through a comparative analysis of protocol performance on molecular systems such as Hâ‚‚, Hâ‚‚O, and Nâ‚‚, we validate these techniques and discuss their critical role in accelerating the discovery of new pharmaceuticals and materials by enabling more accurate quantum computations of molecular properties.

Understanding Quantum Noise and the Need for Error Mitigation in Chemistry Simulations

The Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) era, a term coined by John Preskill, is defined by quantum processors containing up to approximately 1,000 qubits that operate without the benefit of full quantum error correction [1]. These devices are characterized by inherent noise sensitivity and proneness to quantum decoherence, which severely limits the depth and complexity of computations that can be reliably executed [1]. For researchers in quantum chemistry and drug development, this presents both an unprecedented opportunity and a significant challenge. Quantum computers offer the potential to solve electronic structure problems and simulate molecular systems with complexity far beyond the reach of classical computational methods. However, extracting chemically meaningful results—particularly those meeting the standard of chemical accuracy (1.6 × 10â»Â³ Hartree, or approximately 1 kcal/mol)—requires sophisticated strategies to manage the hardware limitations endemic to current devices [2] [3].

The core challenge lies in the exponential scaling of quantum noise. With typical two-qubit gate error rates ranging from 1% to 5% on current hardware, quantum circuits can only execute approximately 1,000 gates before noise overwhelms the signal [1]. This constraint directly impacts the feasibility of running Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) algorithms for molecular energy estimation, as the required circuit depths for interesting chemical systems often approach or exceed this threshold [2]. Furthermore, the limited coherence times of qubits—typically lasting for tens to hundreds of microseconds—impose a strict temporal bound on computation, while measurement errors and crosstalk introduce additional sources of inaccuracy [4] [5]. Understanding and mitigating these effects is not merely an academic exercise but a practical necessity for researchers aiming to leverage NISQ hardware for computational chemistry and pharmaceutical development.

Quantitative Analysis of NISQ Hardware Limitations

Current Hardware Performance Specifications

The performance of NISQ devices is quantified by several key metrics that directly impact the fidelity of quantum chemistry simulations. The table below summarizes representative specifications for leading quantum hardware platforms, illustrating the current landscape of available resources.

Table 1: Representative Performance Metrics of Current NISQ Hardware

| Hardware Platform/Type | Qubit Count | Single-Qubit Gate Fidelity | Two-Qubit Gate Fidelity | Readout Fidelity | Coherence Time (T1/T2, μs) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Superconducting (e.g., IBM) | 50-1000+ | 99.95% | 99.0-99.5% | 97-99% | 100-500 |

| Trapped Ion (e.g., Quantinuum) | 20-50 | 99.99% | 99.5-99.9% | >99% | 10,000+ |

| Neutral Atom (e.g., Atom Computing) | 100-1200 | >99.9% | >99.5% | >98% | 1000+ |

These specifications, derived from current industry capabilities, highlight the fundamental constraints facing NISQ-era quantum chemists [1] [6] [7]. The gate infidelities, though seemingly small, accumulate rapidly as circuit depth increases. For a quantum circuit with 1,000 two-qubit gates, even a 99.5% fidelity per gate would result in a total circuit fidelity of less than 1% (0.995¹â°â°â° ≈ 0.0067). This exponential decay of computational fidelity represents the primary obstacle to achieving chemical accuracy for anything beyond the smallest molecular systems.

Tolerable Error Thresholds for Quantum Chemistry Applications

The stringent precision requirements of computational chemistry demand exceptionally low error rates for useful computation. Recent density-matrix simulations have quantified the relationship between algorithm performance and hardware errors, providing concrete targets for hardware development and error mitigation strategies.

Table 2: Maximally Tolerable Gate-Error Probabilities (p_c) for VQE to Achieve Chemical Accuracy [2]

| Molecular System Size (Orbitals) | Required p_c (Without Error Mitigation) | Required p_c (With Error Mitigation) | Typical Two-Qubit Gate Count (N_II) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Small (4-8) | 10â»â¶ to 10â»âµ | 10â»â´ to 10â»Â³ | 10² - 10³ |

| Medium (10-14) | 10â»â¶ to 10â»â´ | 10â»â´ to 10â»Â² | 10³ - 10â´ |

| Large (>16) | <10â»â¶ | <10â»â´ | >10â´ |

The data reveals a critical scaling relation: the maximally allowed gate-error probability for any VQE to achieve chemical accuracy decreases approximately as ( {p}{c} \propto {N}{II}^{-1} ), where ( N_{II} ) is the number of noisy two-qubit gates [2]. This inverse relationship underscores that as molecular complexity increases, even more stringent error control is required. Furthermore, iterative VQE algorithms such as ADAPT-VQE demonstrate better noise resilience compared to fixed-ansatz approaches like UCCSD, as they typically generate shallower circuits tailored to the specific molecular system [2].

Experimental Protocols for Error Characterization and Mitigation

Protocol 1: Zero-Noise Extrapolation (ZNE) with Qubit Error Probability (QEP) Scaling

Zero-Noise Extrapolation is a widely adopted error mitigation technique that intentionally amplifies circuit noise to extrapolate results back to the zero-noise limit. Traditional ZNE methods that simply multiply circuit layers provide poor noise scaling estimates. The following protocol incorporates a more accurate Qubit Error Probability metric for enhanced precision [4].

Application: Mitigating gate errors in variational quantum algorithms for molecular energy estimation.

Materials and Setup:

- Quantum hardware backend (e.g., IBM Osaka/Kyoto, Quantinuum H1)

- Calibration data for target device (T1, T2 times, gate error rates, readout errors)

- Classical post-processing environment (e.g., Python with Mitiq, Qiskit)

Procedure:

- Circuit Preparation: Implement the target quantum circuit (e.g., VQE ansatz for molecular Hamiltonian).

- QEP Calculation: For each qubit in the register, compute the individual error probability as a function of:

- Native gate fidelities

- Idle time during execution (decoherence)

- Crosstalk from neighboring qubits

- Noise Scaling: Artificially scale noise using pulse-stretching techniques or identity insertion, using QEP rather than simple gate counts to calibrate the scaling factor.

- Data Acquisition: Execute the scaled circuits (e.g., at 1x, 2x, and 3x base QEP levels) with sufficient shots for statistical significance (typically 10â´-10ⶠper circuit).

- Extrapolation: Fit the measured expectation values (e.g., energy) versus QEP to a linear, exponential, or Richardson model and extrapolate to zero QEP.

Validation: Execute on a classically simulable system (e.g., Hâ‚‚ molecule in minimal basis) and compare the ZNE-corrected energy to the exact full configuration interaction (FCI) result. Successful mitigation should reduce the absolute error below the chemical accuracy threshold of 1.6 mHa [4] [3].

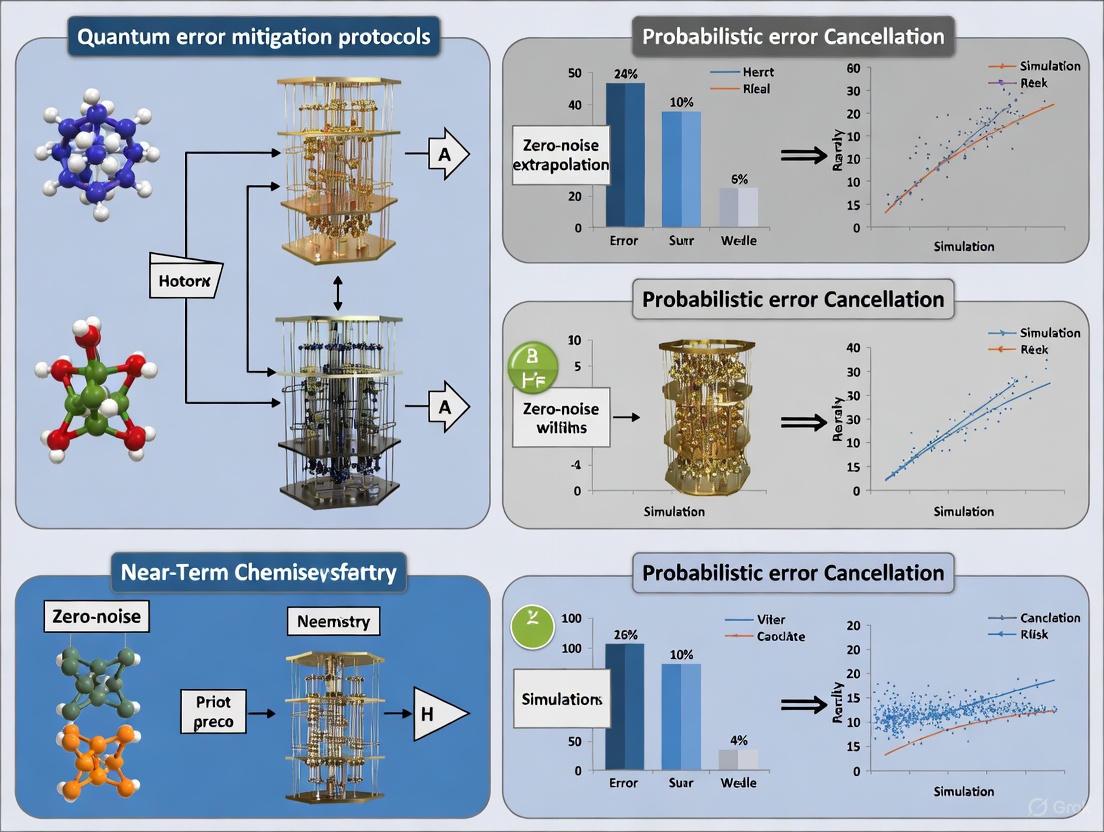

Figure 1: Zero-Noise Extrapolation (ZNE) workflow using Qubit Error Probability (QEP) for precise noise scaling and mitigation.

Protocol 2: Multireference-State Error Mitigation (MREM) for Strongly Correlated Systems

Strongly correlated molecular systems, such as those encountered in transition metal complexes or bond dissociation processes, present particular challenges for quantum simulation. The standard Reference-state Error Mitigation (REM) method, which uses a single Hartree-Fock reference state, fails in these multireference scenarios. The MREM protocol addresses this limitation [8].

Application: Error mitigation for VQE simulations of strongly correlated molecules (e.g., Nâ‚‚, Fâ‚‚, metal oxides).

Materials and Setup:

- Classical computational chemistry software (e.g., PySCF, ORCA) for multireference state selection

- Quantum hardware or simulator with support for generalized gates

- Circuit construction tools for Givens rotations

Procedure:

- Reference Selection: Classically compute a compact multireference wavefunction composed of a few dominant Slater determinants using inexpensive methods (e.g., CASSCF(2,2), DMRG, or selected CI).

- Circuit Construction: Implement the multireference state on the quantum processor using Givens rotation circuits, which preserve particle number and spin symmetry.

- Noise Characterization: Prepare and measure the multireference state on the quantum device to characterize the device-specific noise profile.

- Target State Execution: Run the VQE algorithm to prepare the target molecular ground state and measure its noisy energy, ( E_{\text{noisy}} ).

- Error Estimation: Compute the exact energy of the multireference state, ( E{\text{MR, exact}} ), classically and measure its noisy counterpart, ( E{\text{MR, noisy}} ), on the device.

- Mitigation: Apply the correction: ( E{\text{mitigated}} = E{\text{noisy}} - (E{\text{MR, noisy}} - E{\text{MR, exact}}) ).

Validation: Apply to the nitrogen molecule at dissociation, where the Hartree-Fock state fails. Successful MREM should recover potential energy curves smoothlty across the dissociation coordinate, maintaining chemical accuracy where single-reference REM fails [8].

Protocol 3: Measurement Error Mitigation with Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT)

Readout errors represent a dominant noise source in precision measurement applications. This protocol leverages Quantum Detector Tomography to fully characterize and mitigate measurement errors, enabling high-precision energy estimation [9].

Application: Achieving chemical precision measurements for molecular energy estimation, particularly for complex observables with many Pauli terms.

Materials and Setup:

- Quantum device with configurable measurement basis

- Parallel compilation tools for efficient circuit scheduling

- Classical post-processing infrastructure for tomographic reconstruction

Procedure:

- Calibration Circuit Generation: Prepare and execute a complete set of informationally complete calibration circuits (e.g., all possible input basis states for n-qubits).

- Noise Matrix Construction: Measure the output statistics for each calibration circuit to construct the assignment probability matrix (A), where ( A_{ij} = P(\text{measure outcome } i | \text{prepared state } j) ).

- Blended Scheduling: Interleave calibration circuits with actual chemistry circuits (e.g., Hartree-Fock state preparation with Hamiltonian measurement) to average over temporal noise fluctuations.

- Mitigated Estimation: For the actual experiment outcomes (raw probability vector ( \vec{p}{\text{raw}} )), compute the mitigated probabilities by applying the inverse (or pseudo-inverse) of the assignment matrix: ( \vec{p}{\text{mitigated}} = A^{-1} \vec{p}_{\text{raw}} ).

- Observable Calculation: Compute the expectation value of the molecular Hamiltonian using the mitigated probability distribution.

Validation: Execute the protocol for the BODIPY molecule on an IBM Eagle processor. Successful implementation has demonstrated a reduction in measurement errors from 1-5% to 0.16%, approaching chemical precision [9].

Figure 2: High-precision measurement workflow using Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT) and blended scheduling to mitigate readout errors in molecular energy estimation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Resources for NISQ-Era Quantum Chemistry Experiments

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantum Hardware Platforms | IBM Osaka/Kyoto (Superconducting), Quantinuum H1/H2 (Trapped Ion) | Execution of quantum circuits for molecular energy estimation | Variable qubit count/quality, native gate sets, connectivity [6] [5] |

| Error Mitigation Software | Mitiq, Qiskit Runtime, True-Q | Implementation of ZNE, PEC, REM/MREM protocols | Hardware-agnostic, integrates with popular QC SDKs [4] [10] |

| Classical Computational Chemistry Tools | PySCF, ORCA, Q-Chem | Molecular integral computation, active space selection, reference state generation | Prepares fermionic Hamiltonians and initial states for VQE [8] |

| Quantum Algorithm Libraries | TEQUILA, Qiskit Nature, PennyLane | Implementation of VQE, ADAPT-VQE, QAOA for chemistry | Provides parameterized ansätze and classical optimizers [2] |

| Characterization & Benchmarking Tools | Randomized Benchmarking, Gate Set Tomography, TED-qc | Quantification of gate errors, coherence times, and Qubit Error Probability (QEP) | Establishes device-specific error models for mitigation [4] [7] |

| HIF1-IN-3 | HIF1-IN-3, MF:C26H24N2O3, MW:412.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| 7030B-C5 | 8-[(2-Hydroxyethyl)amino]-7-[(3-methoxyphenyl)methyl]-1,3-dimethyl-2,3,6,7-tetrahydro-1H-purine-2,6-dione | High-purity 8-[(2-HYDROXYETHYL)AMINO]-7-[(3-METHOXYPHENYL)METHYL]-1,3-DIMETHYL-2,3,6,7-TETRAHYDRO-1H-PURINE-2,6-DIONE for research use only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary diagnosis or therapeutic use. | Bench Chemicals |

The path toward quantum utility in computational chemistry and drug development hinges on the co-design of algorithms, error mitigation strategies, and hardware capabilities. The protocols and analyses presented here demonstrate that while significant challenges remain, systematic error management can already yield chemically meaningful results for appropriately scaled problems on current NISQ devices. The integration of physical insights—such as the use of multireference states in MREM—with sophisticated mitigation techniques like ZNE and QDT represents the cutting edge of NISQ-era quantum computational chemistry.

Looking forward, the transition beyond the NISQ era will be marked by the implementation of practical quantum error correction, as recently demonstrated in preliminary experiments on trapped-ion systems [6]. However, for the foreseeable future, error mitigation rather than full correction will remain the primary strategy for extracting value from quantum simulations. Researchers in pharmaceutical and materials science should prioritize engaging with these rapidly evolving techniques, focusing initially on benchmark systems with clear classical references to build institutional expertise. As hardware continues to improve—with gate fidelities approaching 99.99% and quantum volume increasing—the application of these protocols will enable the treatment of increasingly complex molecular systems, potentially transforming the discovery pipelines for new therapeutics and functional materials.

The successful implementation of quantum algorithms, particularly for high-precision fields like quantum chemistry simulation, is critically dependent on understanding and managing the diverse sources of noise in quantum systems. These noise sources introduce errors that can rapidly degrade computational accuracy, making their systematic characterization a prerequisite for effective error mitigation [9]. For near-term quantum hardware, where full-scale error correction remains impractical, developing noise-resilient protocols is essential for achieving chemically meaningful results, such as molecular energy estimation to within chemical accuracy (1.6 mHa) [3] [9]. This application note provides a structured framework for identifying, quantifying, and mitigating the predominant sources of quantum noise, with a specific focus on applications in quantum computational chemistry.

Quantum noise arises from a complex interplay of environmental interactions, control imperfections, and fundamental material properties. The table below categorizes primary noise sources, their physical origins, and their impact on quantum computations.

Table 1: Classification of Primary Quantum Noise Sources

| Noise Category | Specific Type | Physical Origin | Impact on Quantum Computation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental | Thermal Noise [11] | Finite temperature fluctuations causing Brownian motion. | Limits displacement sensitivity; adds thermal occupation to qubit states. |

| Environmental | Decoherence [12] [13] | Unwanted interaction with the environment (photons, phonons, magnetic fields). | Causes loss of superposition and entanglement, the core quantum resources. |

| Control Imperfections | Control Signal Noise [13] | Imperfections in classical electronics generating control pulses. | Incorrect gate operations (e.g., wrong rotation angles), reducing gate fidelity. |

| Control Imperfections | Readout Errors [9] | Inaccurate measurement operations. | Misassignment of final qubit states (e.g., reading 0 as 1), corrupting results. |

| Fundamental Material | Material Defects [13] | Atomic vacancies, impurities, or grain boundaries in substrate materials. | Creates localized charge/ magnetic fluctuations, leading to unpredictable qubit behavior. |

| Stochastic | Depolarizing Noise [14] | Qubit randomly undergoing one of the Pauli operators (X, Y, Z). |

Fully randomizes the qubit state with a given probability. |

| Stochastic | Amplitude Damping [14] | Energy dissipation, modeling the spontaneous emission of a photon. | Loss of energy from the excited |1> state to the ground |0> state. |

The Fluctuation-Dissipation Theorem provides a fundamental link for certain noise types, such as thermal noise. The displacement power spectral density due to thermal noise can be modeled as: [S{\mathrm{th}}(\omega) = \sum{k=0}^{n} \frac{4kB T \omegak \phi}{mk[(\omega^{2}{k} - \omega^{2})^{2} + \omega^{2} \omega^{2}{k} \phi^{2}]}] where (kB) is Boltzmann's constant, (T) is temperature, (mk) and (\omegak) are the mass and frequency of the (k)th mechanical mode, and (\phi) is the loss angle [11]. This formalizes the direct relationship between dissipation (encoded in (\phi)) and the resulting fluctuations.

Experimental Protocols for Noise Characterization

Accurate noise characterization is the foundation of effective mitigation. The following protocols provide methodologies for quantifying key noise parameters.

Protocol for Characterizing Thermal Noise and Mechanical Loss

This protocol is designed to characterize the thermal noise contribution in systems such as suspended mirror microresonators, which is critical for high-precision interferometric measurements [11].

- Apparatus Setup: Incorporate the device under test (e.g., a GaAs/AlGaAs micro-mirror suspended on a cantilever) as the end-mirror in a Fabry–Pérot optical cavity. The entire setup must be housed in a high-vacuum chamber (e.g., at ∼10â»â¸ torr) and cryogenically cooled to target temperatures (e.g., 25 K) to mitigate viscous damping and reduce thermal noise [11].

- Quality Factor (

Q) Measurement: Perform a ring-down measurement. Excite the mechanical resonator, then observe the exponential decay of its amplitude. The quality factor is calculated as (Q = \omega0 / \Delta\omega), where (\omega0) is the resonant frequency and (\Delta\omega) is the linewidth of the resonance. A highQ(e.g., 25,000 ± 2,200) indicates low mechanical loss [11]. - Spectral Measurement: Use the optical cavity to measure the displacement power spectral density (PSD) of the mirror's motion. The measured PSD will contain peaks corresponding to the mechanical resonant frequencies.

- Modal Mass Estimation: Fit the measured noise spectra to a model based on the fluctuation-dissipation theorem (e.g., Equation 1). The known temperature (

T), frequency (ω_k), and measuredQfactor allow for the extraction of the effective modal masses (m_k) for each resonance, which can be cross-verified with finite element analysis (FEA) simulations [11]. - Noise Level Quantification: Compare the magnitude of the characterized thermal noise PSD to the Standard Quantum Limit (SQL), often reported in decibels (dB) below the SQL [11].

Protocol for Quantum Noise Channel Identification via QBER

This protocol leverages simple Quantum Key Distribution (QKD) circuits and classical Machine Learning (ML) to identify dominant noise channels in a processor, a method applicable to low-qubit, noisy devices [14].

- Circuit Preparation: Select a simple QKD protocol, such as BB84 or BBM92, which requires only single-qubit or two-qubit gates [14].

- Data Generation:

a. Simulation: Simulate the QKD circuits on a classical computer, explicitly injecting known noise channels (e.g., bit-flip, amplitude damping, depolarizing) with varying strengths (

p). b. Hardware Execution: Run the same QKD circuits on the target near-term quantum processor. - Metric Extraction: For each execution (simulated or hardware), calculate the Quantum Bit Error Rate (QBER), which is the fraction of mismatched bits in the final key between the two protocol parties.

- Model Training: Use the simulation-generated data (QBER values and the corresponding known noise type) as a labeled training set. Train supervised ML classifiers, such as K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), Gaussian Naive Bayes, or Support Vector Machines (SVM) [14].

- Noise Identification: Feed the QBER data collected from the hardware runs into the trained ML model. The model will output a classification for the dominant noise type present in the hardware.

Workflow for Integrated Noise Characterization

The diagram below illustrates the logical sequence and decision points in a comprehensive noise characterization workflow, integrating elements from the protocols above.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This section details the essential components and techniques required for advanced quantum noise characterization and mitigation experiments.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Quantum Noise Studies

| Tool / Material | Function / Specification | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Low-Noise Mirror Microresonators (e.g., GaAs/AlGaAs) [11] | High-reflectivity mirror coatings with low mechanical loss, suspended as cantilevers. | Serves as a test mass for probing thermal noise in ultra-sensitive measurements. |

| Optical Cavities & Readout (e.g., Fabry–Pérot) [11] | Provides a highly sensitive platform for measuring displacement and forming an "optical spring" to manipulate dynamics. | Used to probe thermal noise and quantum radiation pressure noise below the Standard Quantum Limit. |

| Cryogenic Systems [11] [13] | Dilution refrigerators cooling to millikelvin (mK) temperatures, often paired with vacuum chambers. | Reduces thermal noise by freezing out environmental energy fluctuations. |

| Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT) [9] | A protocol to fully characterize the noisy measurement process of a quantum device by reconstructing its Positive Operator-Valued Measure (POVM). | Mitigates readout errors in high-precision tasks like molecular energy estimation, reducing systematic bias. |

| Informationally Complete (IC) Measurements [9] | A set of measurement settings that fully characterizes the quantum state, allowing estimation of multiple observables from the same data. | Reduces circuit overhead and enables efficient error mitigation via post-processing. |

| Density Matrix Simulators [15] | Quantum simulators (e.g., Amazon Braket DM1) that use density matrices instead of state vectors. | Essential for simulating open quantum systems, decoherence, and general noise channels before running on hardware. |

| MMV006833 | MMV006833, MF:C19H27ClN2O4S, MW:414.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| CA IX-IN-3 |

Error Mitigation Protocols for Quantum Chemistry Simulations

Leveraging accurate noise characterization, the following advanced protocols are specifically designed to enhance the fidelity of quantum chemistry computations on near-term devices.

Multireference-State Error Mitigation (MREM)

The standard Reference-State Error Mitigation (REM) method uses a single, easily prepared reference state (e.g., Hartree-Fock) to calibrate energy errors. However, its effectiveness is limited for strongly correlated systems where the true ground state is a complex combination of multiple Slater determinants. MREM addresses this by using a multireference state with significant overlap to the target ground state [8].

- Multireference State Generation: Classically compute a compact multireference wavefunction for the target molecule (e.g., using a selected CI or CASSCF method). This state is a truncated linear combination of dominant Slater determinants.

- Quantum Circuit Preparation: Prepare the multireference state on the quantum processor. This can be efficiently achieved using circuits composed of Givens rotations, which are universal for state preparation and preserve particle number and spin symmetry [8].

- Noisy Energy Estimation: Measure the energy expectation value of the Hamiltonian with respect to the prepared multireference state on the noisy quantum device, yielding (E_{\text{noisy}}^{\text{MR}}).

- Classical Energy Calculation: Classically and exactly compute the energy of the same multireference state, (E_{\text{exact}}^{\text{MR}}).

- Error Calibration & Mitigation: The energy error for the multireference state is (\Delta{\text{MR}} = E{\text{noisy}}^{\text{MR}} - E{\text{exact}}^{\text{MR}}). This error is assumed to be similar for the target state. If (E{\text{noisy}}^{\text{Target}}) is the measured energy of the target VQE state, the mitigated energy is: [ E{\text{mitigated}} = E{\text{noisy}}^{\text{Target}} - \Delta_{\text{MR}} ] This procedure significantly improves accuracy for strongly correlated systems like the bond-stretching regions of Nâ‚‚ and Fâ‚‚ molecules [8].

Protocol for High-Precision Readout Error Mitigation

Achieving chemical precision (1.6×10â»Â³ Ha) in energy estimation requires aggressive mitigation of readout errors, which can be 1-5% on typical devices [9].

- Implement Informationally Complete (IC) Measurements: Choose a set of measurement bases that fully characterize the state. Techniques like Locally Biased Classical Shadows can be used to reduce the shot overhead of this step by prioritizing measurement settings that have a larger impact on the energy estimation [9].

- Parallel Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT): Interleave the execution of the chemistry circuits with circuits dedicated to QDT. This involves preparing a complete set of basis states (

|0...0>,|0...1>, ...,|1...1>) and measuring them to reconstruct the device's noisy measurement operator [9]. - Blended Scheduling: To mitigate time-dependent noise (drift), schedule all circuits (chemistry and QDT) in a blended, interleaved manner rather than in large sequential blocks. This ensures temporal fluctuations affect all computations equally on average [9].

- Post-Processing with Calibrated Noise Model: Use the measurement operator obtained from QDT to construct an unbiased estimator for the molecular energy during classical post-processing. This corrects the raw measurement outcomes, reducing estimation bias and enabling errors as low as 0.16% [9].

Workflow for Noise-Resilient Quantum Metrology

This workflow, which integrates quantum sensing with quantum computing, can be adapted to enhance the precision of quantum chemistry observables.

The core innovation is processing the noisy quantum state Ï̃ on a quantum computer without converting it to classical data, thus avoiding a major bottleneck. Techniques like quantum Principal Component Analysis (qPCA) can then filter out the dominant noise, yielding a purified state Ï_NR from which the parameter (e.g., a molecular energy) can be estimated with significantly enhanced accuracy and precision, as quantified by the Quantum Fisher Information [16].

The transformative potential of quantum computing for simulating molecular systems in chemistry and drug development is currently constrained by a fundamental challenge: the high error rates inherent in today's quantum hardware. Quantum bits (qubits) are exceptionally fragile, with current physical error rates typically around 1 in 100 to 1 in 10,000 operations [17]. These errors arise from environmental disturbances, decoherence, and imperfect gate operations, degrading computational results and limiting the scale of feasible quantum simulations.

To address this challenge, two distinct but complementary approaches have emerged: Quantum Error Mitigation (QEM) and Quantum Error Correction (QEC). For researchers focused on near-term quantum chemistry applications, understanding the practical trade-offs between these approaches is critical for designing viable experimental protocols. This application note provides a structured comparison of QEM and QEC strategies, detailing their operational principles, resource requirements, and practical implementation for quantum simulations in chemical research.

Core Conceptual Differences

Fundamental Operational Principles

Quantum Error Mitigation and Quantum Error Correction represent philosophically distinct approaches to managing errors in quantum computations, each with characteristic mechanisms and objectives.

Quantum Error Mitigation (QEM): QEM encompasses a suite of post-processing techniques that infer less noisy results from multiple executions of noisy quantum circuits. Rather than preventing errors during computation, QEM allows errors to occur and subsequently "averages out" their impact through classical post-processing of measurement results [18] [19]. As summarized by one expert, "Error mitigation focuses on techniques for noticing that a shot is bad, or for quantifying how a shot is bad. You run lots and lots of shots, and use the good-vs-bad signals to get better estimates of some quantity" [20]. These methods are generally application-specific, particularly effective for expectation value estimation rather than full distribution sampling [18].

Quantum Error Correction (QEC): QEC takes a preventive approach by encoding quantum information across multiple physical qubits to create more robust logical qubits. Through repetitive cycles of syndrome measurement, decoding, and correction, QEC actively detects and corrects errors as they occur during computation [19] [21]. This approach aims to implement fault-tolerant quantum computation, where errors are suppressed sufficiently to allow for arbitrarily long calculations, provided physical error rates remain below a certain threshold [17]. "QEC doesn't 'end' the existence of errors—it reduces their likelihood," notes one technical guide, highlighting that the objective is progressive error suppression rather than complete elimination [18].

Comparative Analysis Framework

The table below summarizes the key characteristics and trade-offs between QEM and QEC approaches:

| Characteristic | Quantum Error Mitigation (QEM) | Quantum Error Correction (QEC) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Objective | Extract correct signal from noisy outputs through post-processing [20] | Make each quantum computation shot inherently reliable [20] |

| Primary Mechanism | Classical post-processing of results from multiple circuit variants [19] | Encoding logical qubits across physical qubits with real-time correction [19] [17] |

| Hardware Overhead | Low physical qubit overhead | High physical qubit overhead (100+:1 ratio common) [18] [21] |

| Temporal Overhead | Exponential shot overhead with circuit size [18] | Circuit slowdown (1000x-1,000,000x) but no exponential shot scaling [18] [20] |

| Error Types Addressed | Both coherent and incoherent errors [18] | All error forms (including qubit loss) with appropriate codes [18] |

| Application Scope | Estimation tasks (expectation values) [18] | Universal (any algorithm on logical qubits) [18] |

| Implementation Timeline | Near-term (current devices) | Long-term (requiring more advanced hardware) [18] [17] |

| Key Limitation | Exponential resource scaling with circuit size [18] [22] | Massive resource requirements for useful logical error rates [18] [21] |

Table 1: Comparative analysis of Quantum Error Mitigation and Quantum Error Correction approaches.

Quantum Error Mitigation: Protocols for Near-Term Chemistry Simulations

Core QEM Techniques and Workflows

For quantum chemistry applications such as molecular energy estimation, several QEM techniques have demonstrated practical utility on current hardware. These include Zero-Noise Extrapolation (ZNE), Probabilistic Error Cancellation (PEC), and measurement error mitigation, each with distinct operational principles and resource requirements.

The following workflow illustrates a typical quantum error mitigation protocol for chemistry simulations:

Figure 1: Quantum Error Mitigation Workflow for Molecular Energy Estimation.

Practical Implementation: Molecular Energy Estimation Case Study

Recent research demonstrates the successful application of QEM techniques for high-precision molecular energy estimation. A 2025 study published in npj Quantum Information implemented a comprehensive measurement protocol for the BODIPY molecule on IBM quantum hardware, achieving a significant reduction in measurement errors from 1-5% to 0.16% [9].

The experimental protocol incorporated these key techniques:

Informationally Complete (IC) Measurements: Enabled estimation of multiple observables from the same measurement data and provided a framework for efficient error mitigation [9].

Locally Biased Random Measurements: Reduced shot overhead by prioritizing measurement settings with greater impact on energy estimation [9].

Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT): Characterized readout errors to create an unbiased estimator for molecular energy, significantly reducing estimation bias [9].

Blended Scheduling: Mitigated time-dependent noise by interleaving circuit executions, ensuring homogeneous noise exposure across all measurements [9].

This integrated approach demonstrates that chemical precision (1.6×10â»Â³ Hartree) is achievable on current hardware for moderately sized quantum chemistry problems through sophisticated error mitigation strategies.

Quantum Error Correction: Towards Fault-Tolerant Chemistry Simulations

QEC Fundamentals and Implementation Architecture

Quantum Error Correction represents the foundational approach for achieving truly scalable quantum computation. Unlike error mitigation, QEC employs quantum codes to proactively protect information during computation through spatial redundancy and active feedback.

The following diagram illustrates the continuous cycle of real-time quantum error correction:

Figure 2: Quantum Error Correction Cycle with Real-Time Feedback.

Practical QEC Demonstration and Resource Requirements

Recent experimental milestones demonstrate progress in implementing QEC, though practical challenges remain for chemistry-scale applications:

Google's Willow Chip: Implemented the surface code with a 7×7 qubit array, demonstrating a 2.14-fold error reduction with each scaling stage and operating below the critical error threshold for the first time [21].

Resource Overheads: Current QEC implementations require substantial resource investment. Google's experiment used 105 physical qubits to realize a single logical qubit [18], while practical fault-tolerant systems may require 100-1000 physical qubits per logical qubit depending on the code and physical error rates [21].

Real-Time Decoding Challenge: A critical bottleneck for practical QEC is the need for high-speed, low-latency decoding. "For feedback-based QEC, low latency is essential," notes Qblox, with control stacks requiring deterministic feedback networks capable of sharing measurement outcomes within ≈400ns across modules [21].

These demonstrations represent significant progress but highlight that QEC for complex chemistry simulations requiring many logical qubits remains a future prospect given current hardware limitations.

Hybrid Approaches: Integrating QEM and QEC for Near-Term Applications

Hybrid Protocol Design and Workflow

Recognizing the complementary strengths of both approaches, researchers have begun developing hybrid protocols that integrate elements of QEM and QEC. These approaches aim to balance resource overhead and error suppression capabilities for near-term applications.

A 2025 hybrid protocol combines the [[n,n−2,2]] quantum error detection code (QEDC) with probabilistic error cancellation (PEC) and modified Pauli twirling [22]. This approach leverages the constant qubit overhead and simple post-processing of QEDC while using PEC to address undetectable errors that escape the detection code.

The following workflow illustrates this integrated approach:

Figure 3: Hybrid Quantum Error Detection and Mitigation Protocol.

Practical Implementation and Advantages

This hybrid protocol demonstrated practical utility in quantum chemistry applications, particularly for variational quantum eigensolver (VQE) circuits estimating the ground state energy of Hâ‚‚ [22]. The approach offers several key advantages:

Reduced Sampling Overhead: By applying PEC to a lower-noise circuit (after error detection), the sampling overhead is substantially reduced compared to applying PEC directly to unprotected circuits [22].

Compatibility with Non-Clifford Operations: The [[n,n−2,2]] code provides simpler encoding schemes for logical rotations, eliminating the need for complex compilation into Clifford+T circuits and avoiding associated approximation errors [22].

Practical QEC Introduction: The constant qubit overhead (only 2 additional qubits regardless of register size) makes this approach feasible on current hardware, serving as an accessible introduction to encoded quantum computation [22].

This hybrid approach demonstrates the potential for strategically combining elements of both QEM and QEC to achieve practical error suppression on current quantum hardware while managing resource constraints.

Research Reagent Solutions for Quantum Error Management

Implementing effective error management strategies for quantum chemistry simulations requires both hardware and software tools. The following table catalogues essential resources mentioned in recent literature:

| Resource/Technique | Function | Example Implementations |

|---|---|---|

| Error Suppression | Proactively reduces error likelihood during circuit execution via optimized control pulses [19] | Boulder Opal [19], Fire Opal [19] |

| Zero-Noise Extrapolation (ZNE) | Extrapolates observable expectations to zero error by intentionally increasing noise levels [18] | Mitiq, Qiskit Runtime |

| Probabilistic Error Cancellation (PEC) | Constructs unbiased estimators by combining results from noisy circuits with quasi-probability distributions [18] [22] | Qiskit, TrueQ |

| Measurement Error Mitigation | Corrects readout errors using confusion matrix tomography [19] [9] | Qiskit, Cirq |

| Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT) | Characterizes noisy measurement effects to build unbiased estimators [9] | Custom implementations |

| Pauli Twirling | Converts coherent errors into stochastic errors via random Pauli operations [22] | Qiskit, PyQuil |

| Real-Time Decoders | Interprets error syndromes and determines corrections within QEC cycles [21] [17] | Deltakit [23], Tesseract [24] |

| QEC Control Stacks | Provides low-latency feedback and scalable control for QEC experiments [21] | Qblox [21] |

Table 2: Essential Resources for Implementing Quantum Error Management Protocols.

The strategic selection between quantum error mitigation and quantum error correction represents a critical design decision for researchers pursuing quantum chemistry simulations. For near-term applications on currently available hardware, quantum error mitigation techniques offer practical pathways to enhanced precision for specific tasks like molecular energy estimation, albeit with exponential scaling limitations. Quantum error correction, while theoretically capable of enabling arbitrary-scale quantum computations, currently demands resource overheads that limit its immediate utility for complex chemistry simulations.

Hybrid approaches that strategically combine error detection with mitigation present a promising intermediate path, offering enhanced error suppression with manageable overheads. As hardware continues to improve, with physical error rates decreasing and qubit counts increasing, the balance between these approaches will inevitably shift toward full quantum error correction. For the present, however, quantum error mitigation and hybrid protocols provide the most viable path toward demonstrating quantum utility in chemistry simulations on near-term devices.

The rapid progress in both domains suggests that effective error management—whether through mitigation, correction, or hybrid approaches—will remain the critical enabling technology for practical quantum chemistry applications in the coming years. Research teams should maintain flexibility in their error management strategies, adopting techniques matched to their specific application requirements and available hardware capabilities.

Impact of Noise on Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) Accuracy

The Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) is a leading hybrid quantum-classical algorithm for determining molecular ground-state energies, with promising applications in drug development and materials science [25]. However, current Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) devices suffer from significant gate and readout errors that severely impact the accuracy and reliability of VQE simulations [26] [2]. Understanding and mitigating these noise effects is crucial for advancing quantum computational chemistry. This application note synthesizes recent findings on noise impacts and provides detailed protocols for error-resilient VQE implementation.

Quantitative Analysis of Noise Impacts

Tolerable Gate Error Probabilities for Chemical Accuracy

Table 1: Maximally allowed gate-error probabilities (p_c) for VQEs to achieve chemical accuracy (1.6 mHa) [2]

| VQE Algorithm Type | Specific Ansatz | Without Error Mitigation | With Error Mitigation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed Ansatz | UCCSD | 10â»â¶ to 10â»â´ | 10â»â´ to 10â»Â² |

| Fixed Ansatz | k-UpCCGSD | 10â»â¶ to 10â»â´ | 10â»â´ to 10â»Â² |

| Adaptive Ansatz | ADAPT-VQE | 10â»â¶ to 10â»â´ | 10â»â´ to 10â»Â² |

Performance Comparison with Error Mitigation

Table 2: Error mitigation impact on VQE accuracy for BeHâ‚‚ simulations [26]

| Quantum Processor | Qubit Count | Error Mitigation | Accuracy vs Exact (Orders of Magnitude) | Key Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IBMQ Belem | 5 | None | ~10â»Â¹ (Baseline) | Reference point |

| IBMQ Belem | 5 | T-REx | ~10â»Â² (Improvement) | 10x improvement with mitigation |

| IBM Fez | 156 | None | ~10â»Â¹ (Similar to unmigitated Belem) | Smaller, older device with mitigation outperforms larger, newer device without mitigation |

Experimental Protocols for Noise-Resilient VQE

Protocol 1: Twirled Readout Error Extinction (T-REx) Implementation

Purpose: Mitigate readout errors to improve VQE parameter quality and energy estimation [26]

Materials:

- Quantum processor or simulator with readout error characterization capabilities

- Classical optimization routine (e.g., SPSA)

- Circuit twirling components

Procedure:

- Characterize Readout Error: Execute comprehensive readout calibration using prepared computational basis states.

- Construct T-REx Filters: Derive optimal filters from calibration data to correct readout probabilities.

- Integrate with VQE Loop:

- During each energy evaluation, apply T-REx filtering to measurement outcomes.

- Use corrected probabilities for expectation value calculation.

- Optimize Parameters: Proceed with classical optimization using error-mitigated energies.

- Validate Results: Compare mitigated results with state-vector simulations to verify parameter quality.

Protocol 2: Gate Error Resilience Benchmarking

Purpose: Quantify VQE algorithm performance under depolarizing noise [2]

Materials:

- Density-matrix simulator with configurable noise models

- Molecular Hamiltonians (4-14 orbitals)

- VQE ansätze (UCCSD, k-UpCCGSD, ADAPT-VQE)

Procedure:

- Setup Noise Model: Configure depolarizing noise channels with target error probabilities (10â»â¶ to 10â»Â²).

- Execute Noisy Simulations: For each molecule and ansatz type:

- Run complete VQE optimization under noisy conditions.

- Record final energy error from exact diagonalization.

- Determine Threshold: Identify the maximum error probability (p_c) maintaining chemical accuracy.

- Analyze Scaling: Fit pc versus number of two-qubit gates (NII) to establish ({p}{c}\mathop{\propto }\limits{ \sim }{N}_{{{{\rm{II}}}}}^{-1}) relationship.

Protocol 3: Quantum-DFT Embedding Workflow

Purpose: Simulate complex materials while mitigating NISQ limitations [27] [28]

Materials:

- Qiskit Nature framework (v43.1+)

- PySCF electronic structure package

- Molecular structures from CCCBDB or JARVIS-DFT

Procedure:

- Structure Generation: Obtain pre-optimized molecular geometries from databases.

- Active Space Selection: Use ActiveSpaceTransformer to identify correlated regions (e.g., 3 orbitals, 4 electrons for Al clusters).

- Hamiltonian Generation: Perform single-point calculations and map electronic Hamiltonian to qubits via Jordan-Wigner transformation.

- VQE Execution:

- Employ hardware-efficient ansatz (e.g., EfficientSU2) or chemically-inspired ansatz.

- Optimize parameters using SLSQP or other suitable optimizers.

- Validation: Compare with NumPy exact diagonalization and CCCBDB reference data.

Workflow Diagrams

VQE Error Mitigation Protocol

Quantum-DFT Embedding Methodology

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential research reagents for noise-resilient VQE experiments

| Reagent Solution | Function | Example Implementations |

|---|---|---|

| Error Mitigation Protocols | Reduce hardware noise impact on measurements | T-REx [26], Zero-Noise Extrapolation, Probabilistic Error Cancellation |

| Adaptive Ansätze | Construct circuit structures iteratively for noise resilience | ADAPT-VQE [2], tUCCSD [29] |

| Quantum-Digital Embedding | Combine quantum and classical computational resources | Quantum-DFT Embedding [27] [28] |

| Classical Optimizers | Navigate noisy parameter landscapes effectively | SPSA [26], SLSQP [27] |

| Hardware-Efficient Ansätze | Minimize circuit depth for NISQ devices | EfficientSU2 [27], QNP [29] |

| Measurement Reduction | Decrease shot noise and measurement overhead | Pauli saving [29], measurement grouping |

| Aminopeptidase-IN-1 | Aminopeptidase-IN-1, MF:C18H16N2O6, MW:356.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| p53-MDM2-IN-4 | p53-MDM2-IN-4, MF:C23H20FN3O3, MW:405.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The accuracy of VQE simulations on NISQ devices is profoundly affected by quantum noise, with gate error probabilities needing to be below 10â»â´ to 10â»Â² even with error mitigation to achieve chemical accuracy [2]. The integration of error mitigation strategies like T-REx [26] with advanced ansätze and quantum-classical embedding approaches provides a viable path toward meaningful quantum computational chemistry applications. As hardware continues to improve, these protocols will enable researchers to extract increasingly accurate molecular simulations from noisy quantum processors.

Quantum Error Mitigation (QEM) has emerged as a crucial suite of techniques for extracting reliable results from noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices. Unlike quantum error correction, which aims to physically correct errors in real-time, QEM reduces the impact of noise through classical post-processing of results from multiple quantum circuit executions [30]. For computational chemistry and drug development research, these protocols enable more accurate simulations of molecular systems and reaction mechanisms on current quantum hardware, bridging the gap between theoretical potential and practical application. This application note provides a detailed overview of two foundational QEM protocols—Zero-Noise Extrapolation (ZNE) and Probabilistic Error Cancellation (PEC)—with specific guidance for their implementation in near-term chemistry simulations.

Theoretical Foundations

Zero-Noise Extrapolation (ZNE)

ZNE operates on the principle of artificially amplifying circuit noise in a controlled manner, executing the circuit at these elevated noise levels, and mathematically extrapolating the results back to a hypothetical zero-noise scenario [31] [32]. The core assumption is that the relationship between noise strength and observable expectation values follows a smooth, predictable pattern, typically modeled as exponential decay:

⟨O⟩(λ)=ae−bλ+c where ⟨O⟩(λ)=ae−bλ+c\langle O \rangle(\lambda) = a e^{-b\lambda} + ca, aab, and bbc are fitting parameters determined from measurements at different noise levels, and ccλ represents the noise strength [32].λ\lambda

The technique proceeds through three well-defined stages: noise-scaled circuit generation, execution of these circuits, and extrapolation of results. Noise scaling can be achieved through unitary folding methods, either globally across the entire circuit (λ→λ′=(2n+1)λ) or locally at individual gate levels [31].λ→λ′=(2n+1)λ\lambda \rightarrow \lambda' = (2n+1)\lambda

Probabilistic Error Cancellation (PEC)

PEC employs a fundamentally different approach based on quasi-probability decompositions. The core idea involves representing ideal quantum operations as linear combinations of implementable noisy operations. For an ideal channelI and noisy channel I\mathcal{I}N, if one can find a decomposition:N\mathcal{N}

I=∑jαjNj where I=∑jαjNj\mathcal{I} = \sumj \alphaj \mathcal{N}jNj are implementable noisy operations and Nj\mathcal{N}jαj are real coefficients (which may be negative), then the ideal expectation value can be recovered as:αj\alpha_j

⟨O⟩0=∑jαj⟨O⟩Nj [32]. The sampling overhead for this technique scales approximately as ⟨O⟩0=∑jαj⟨O⟩Nj\langle O \rangle0 = \sumj \alphaj \langle O \rangle{\mathcal{N}_j}e4λ, making it computationally expensive for highly noisy circuits but providing exact bias cancellation when properly characterized [32].e4λe^{4\lambda}

Experimental Protocols

ZNE Protocol for Molecular Energy Estimation

Objective: Estimate the ground-state energy of a molecular system using ZNE.

Preparatory Steps:

- Circuit Compilation: Compile the molecular Hamiltonian (e.g., derived from STO-3G basis) into a quantum circuit using techniques such as Trotterization or variational quantum eigensolver (VQE) ansätze.

- Noise Characterization: Characterize the native noise parameters (λ0) of the target quantum processor using gate set tomography or randomized benchmarking.λ0\lambda_0

- Scale Factor Selection: Choose a set of odd-integer scale factors (e.g., [1, 3, 5]) corresponding to increased noise levelsλk=ckλ0, where λk=ckλ0\lambdak = ck\lambda0ck represents the scale factor [31].ckck

Experimental Workflow:

- Circuit Generation: For each scale factorck, generate noise-scaled circuits using unitary folding:ckck

- Global Folding: Apply the transformationU→U(U†U)n for the entire circuit, where U→U(U†U)nU \rightarrow U(U^\dagger U)^nn=(ck−1)/2 [31].n=(ck−1)/2n = (ck-1)/2

- Local Folding: Apply similar folding to individual gates within the circuit.

- Circuit Execution: Execute each noise-scaled circuit on the quantum processor (or noisy simulator) with sufficient shots (typically 103-106) to obtain expectation values⟨O⟩(λk) for the molecular energy observable.⟨O⟩(λk)\langle O\rangle(\lambda_k)

- Extrapolation: Apply polynomial or exponential extrapolation to estimate the zero-noise value⟨O⟩(0). For polynomial extrapolation with order 2:⟨O⟩(0)\langle O\rangle(0)

- Fit the data points(λk,⟨O⟩(λk)) to a polynomial (λk,⟨O⟩(λk))(\lambdak, \langle O\rangle(\lambdak))p(λ)=a0+a1λ+a2λ2.p(λ)=a0+a1λ+a2λ2p(\lambda) = a0 + a1\lambda + a2\lambda^2

- Extract the zero-noise estimate asa0 [31].a0a0

PEC Protocol for Chemical Observable Measurement

Objective: Mitigate errors in the measurement of chemical observables (e.g., dipole moments, correlation functions) using PEC.

Preparatory Steps:

- Noise Tomography: Fully characterize the noise channelsNj for all native gates in the quantum processor using gate set tomography.Nj\mathcal{N}_j

- Quasi-Probability Decomposition: For each ideal gateUi in the target chemistry circuit, solve the linear system:UiUi Ui=∑jαijN~j where Ui=∑jαijN~jUi = \sumj \alpha{ij} \tilde{\mathcal{N}}jN~j are the characterized noisy gate operations [32].N~j\tilde{\mathcal{N}}j

- Circuit-Specific Decomposition: For the entire circuit implementing unitaryU, compute the overall decomposition:U\mathbf{U} U=âˆiUi=∑j→αj→N~j→ where U=âˆiUi=∑j→αj→N~j→\mathbf{U} = \prodi Ui = \sum{\overrightarrow{j}} \alpha{\overrightarrow{j}} \tilde{\mathcal{N}}{\overrightarrow{j}}j→ represents sequences of noisy operations and j→\overrightarrow{j}αj→=âˆiαiji [33].αj→=âˆiαiji\alpha{\overrightarrow{j}} = \prodi \alpha{ij_i}

Experimental Workflow:

- Circuit Sampling: Sample a noisy circuit implementationN~j→ according to the quasi-probability distribution N~j→\tilde{\mathcal{N}}{\overrightarrow{j}}P(j→)=∣αj→∣/γ, where P(j→)=∣αj→∣/γP(\overrightarrow{j}) = |\alpha{\overrightarrow{j}}|/\gammaγ=∑j→∣αj→∣.γ=∑j→∣αj→∣\gamma = \sum{\overrightarrow{j}} |\alpha{\overrightarrow{j}}|

- Circuit Execution: Execute the sampled noisy circuit on the quantum processor and measure the observableO.OO

- Result Weighting: Weight the measurement outcome by the signsign(αj→)×γ.sign(αj→)×γ\text{sign}(\alpha_{\overrightarrow{j}}) \times \gamma

- Averaging: Repeat steps 1-3 multiple times and average the weighted results to obtain the error-mitigated expectation value.

Quantitative Analysis and Performance Comparison

Table 1: Performance Characteristics of ZNE and PEC for Chemistry Simulations

| Parameter | Zero-Noise Extrapolation (ZNE) | Probabilistic Error Cancellation (PEC) |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Basis | Noise scaling and extrapolation [31] | Quasi-probability decomposition [32] |

| Sampling Overhead | Scales as λ2(n−1) for n noise levels [32] | Scales approximately as e4λ [32] |

| Bias Elimination | Approximate (dependent on extrapolation model) | Exact (with perfect noise characterization) [32] |

| Noise Characterization Requirements | Moderate (noise scaling relationship) | High (full gate set tomography) [32] |

| Optimal Use Cases | Moderate-depth circuits, exploratory calculations | High-precision measurements, small circuits |

| Implementation Complexity | Low to moderate | High |

| Compatibility with Quantum Chemistry Algorithms | VQE, quantum phase estimation | Variational algorithms, observable measurement |

Table 2: Resource Estimation for Chemical System Simulation (Representative Example)

| Protocol | Circuit Depth | Number of Qubits | Required Shots | Effective Error Reduction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unmitigated | 100-500 gates | 10-50 qubits | 103-104 | Baseline |

| ZNE (polynomial) | 100-1500 gates (scaled) | 10-50 qubits | 104-106 | 3-10x improvement [31] |

| PEC | 100-500 gates | 10-50 qubits | 105-108 | 10-100x improvement [32] |

Application to Chemistry Simulations

For quantum chemistry applications, these QEM protocols enable more accurate simulations of molecular properties, reaction pathways, and electronic structure calculations. Quantum embedding theories, which partition systems into active regions treated with high accuracy and environment regions treated with lower-level methods, provide a natural framework for integrating QEM techniques [34]. For instance, strongly-correlated electronic states in molecular active sites or defect centers in materials can be described with effective Hamiltonians whose expectation values are mitigated using ZNE or PEC [34].

Recent advancements include compilation-informed PEC (CIPEC), which simultaneously addresses compilation errors and logical-gate noise, making it particularly relevant for chemistry simulations requiring high precision [33]. This approach uses information about circuit gate compilations to attain unbiased estimation of noiseless expectation values with constant sample-complexity overhead, significantly reducing quantum resource requirements for high-precision chemical calculations [33].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for QEM Experiments

| Resource | Function in QEM Protocols | Example Implementations |

|---|---|---|

| Noisy Quantum Simulators | Emulates realistic hardware noise for protocol validation | Qrack simulator with configurable noise models [31] |

| Quantum Programming Frameworks | Provides infrastructure for circuit compilation and execution | PennyLane, Qiskit, Catalyst [31] |

| Error Mitigation Packages | Implements core ZNE and PEC algorithms | Mitiq, PennyLane noise module [31] [32] |

| Noise Characterization Tools | Characterizes noise channels for PEC quasi-probability decompositions | Gate set tomography, randomized benchmarking protocols |

| Classical Post-Processing Libraries | Performs extrapolation and statistical analysis | SciPy, NumPy, custom extrapolation functions [31] |

| PIN1 inhibitor 6 | PIN1 inhibitor 6, MF:C16H15N3O2S2, MW:345.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Antiviral agent 56 | 2-[(8-Ethoxy-4-methyl-2-quinazolinyl)amino]-5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-4(1H)-quinazolinone | Research-grade 2-[(8-ethoxy-4-methyl-2-quinazolinyl)amino]-5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-4(1H)-quinazolinone for experimental use. For Research Use Only. Not for human, veterinary, or household use. |

Zero-Noise Extrapolation and Probabilistic Error Cancellation represent two foundational approaches to quantum error mitigation with complementary strengths and applications in chemistry simulations. ZNE offers a more accessible entry point with lower implementation overhead, making it suitable for initial explorations on moderate-scale problems. PEC provides higher accuracy at greater computational cost, appropriate for precision measurements on well-characterized quantum processors. As quantum hardware continues to evolve, these protocols will play an increasingly vital role in enabling accurate computational chemistry and materials simulations, ultimately accelerating drug discovery and materials design pipelines.

A Deep Dive into Key Error Mitigation Methods for Molecular Systems

Quantum error mitigation has become an essential component for extracting useful results from noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices. Among the various techniques available, Probabilistic Error Cancellation (PEC) stands out as a leading unbiased method for recovering noiseless expectation values from noisy quantum computations [35]. This protocol is particularly valuable for quantum chemistry simulations, where accurate estimation of molecular energies is crucial for applications in drug development and materials science.

PEC operates by quasiprobabilistically simulating the inverse of noise channels affecting quantum operations [36]. Unlike quantum error correction, which aims to suppress errors in real-time through encoding, PEC works by post-processing results from multiple circuit executions to mathematically invert the effect of noise. This approach provides a practical pathway toward computational utility on current quantum hardware despite the presence of inherent noise.

The fundamental principle underlying PEC is that the inverse of a physical noise channel, while not itself a physical quantum channel, can be represented as a linear combination of physically implementable operations [36]. This representation allows researchers to effectively cancel error effects while accepting an inevitable sampling overhead in exchange for improved accuracy. For quantum chemistry applications, this tradeoff enables the estimation of Hamiltonian expectation values with errors small enough to maintain chemical accuracy—a critical requirement for predictive computational chemistry.

Theoretical Foundations

Core Mathematical Framework

The PEC protocol begins with a noisy quantum circuit ( \mathcal{C} = \Lambda\mathcal{U}l \cdots \Lambda\mathcal{U}1 ), where ( \mathcal{U}_i ) represent ideal unitary gates and ( \Lambda ) denotes the error channel affecting each gate [35]. For simplicity, we assume a consistent error channel, though the method generalizes to gate-dependent noise.

The core operation of PEC involves applying the inverse error channel ( \Lambda^{-1} ) to each noisy operation. For a noise channel ( \Lambda = (1-\epsilon)\mathcal{I} + \epsilon\mathcal{E}' ), the inverse takes the form ( \Lambda^{-1} = (1+\epsilon)\mathcal{I} - \epsilon\mathcal{E}' + \mathcal{O}(\epsilon^2) ), which can be verified through the composition ( \Lambda^{-1}\Lambda = \mathcal{I} ) [35]. The presence of negative coefficients in this decomposition indicates that ( \Lambda^{-1} ) is not a physical quantum channel, necessitating the quasiprobability approach.

The ideal expectation value of a Hamiltonian ( H ) with respect to the initial state ( \rho ) is given by: [ \langle H\rangle0 = \text{Tr}[H\mathcal{U}(\rho)] ] where ( \mathcal{U} ) represents the ideal noiseless circuit. Through PEC, we recover this value using the noisy circuit implementation: [ \langle H\rangle0 = \gamma\mathbb{E}[\text{sgn}(ri)\text{Tr}[H\mathcal{O}i\mathcal{U}\lambda(\rho)]] ] where ( \gamma = \sumi |ri| ) represents the sampling overhead, ( ri ) are the quasiprobability coefficients, and ( \mathcal{O}_i ) are implementable operations [36].

Advanced PEC Formulations

Recent research has developed enhanced PEC formulations that reduce the sampling overhead. The standard PEC approach yields a sampling cost of ( \gamma_{\text{PEC}} \approx (1+2\epsilon)^l ) [35], which is suboptimal compared to the theoretical lower bound of ( (1+\epsilon)^l ) [35].

Binomial PEC represents one such advancement, where each inverse channel is decomposed into identity and non-identity components, reorganizing the circuit as a sum of different powers of the inverse generator [35]. This approach allows deterministic shot allocation based on circuit weights, naturally controlling the bias-variance tradeoff.

Pauli Error Propagation offers another overhead reduction technique, particularly effective for Clifford circuits [37]. By leveraging the well-defined interaction between Clifford operations and Pauli noise, this method combined with classical preprocessing significantly reduces sampling requirements while maintaining estimation accuracy.

Table 1: Comparison of PEC Sampling Overheads

| Method | Sampling Overhead | Circuit Type | Key Innovation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard PEC | ( (1+2\epsilon)^{2l} ) | General | Quasiprobability decomposition |

| Binomial PEC | Between ( (1+\epsilon)^{2l} ) and ( (1+2\epsilon)^{2l} ) | General | Identity/non-identity separation |

| Pauli Propagation | Reduced exponent for Clifford portions | Clifford-dominated | Classical Pauli propagation |

Practical Implementation

Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the complete PEC workflow for estimating Hamiltonian expectation values:

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for PEC Implementation

| Resource | Function | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Noisy Basis Operations | Physical operations for quasiprobability decomposition | Typically Pauli gates or noisy Clifford operations [36] |

| Noise Characterization Protocol | Determines error model parameters | Cycle benchmarking or error reconstruction [36] |

| Quasiprobability Decomposition | Represents inverse noise channels | Optimized to minimize 1-norm of coefficients [35] |

| Monte Carlo Sampler | Generates circuit instances according to quasiprobability distribution | Tracks sign information for each sample [38] |

| Readout Error Mitigation | Corrects measurement errors | Often implemented as separate pre-processing step [3] |

| CSRM617 | CSRM617, CAS:1848237-07-9, MF:C10H13N3O5, MW:255.23 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| NSC260594 | NSC260594, CAS:906718-66-9, MF:C29H24N6O3, MW:504.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Implementation Protocols

Protocol 1: Noise Learning with Mirror Circuits

Mirror circuits provide an effective methodology for benchmarking quantum devices and characterizing noise parameters [38]:

- Circuit Generation: Generate mirror circuits with varying depths using the device's native gate set and connectivity. For each circuit, determine the correct output bitstring.

- Noisy Execution: Execute each mirror circuit on the target quantum processor, collecting measurement statistics.

- Fidelity Calculation: For each circuit, compute the probability of measuring the correct bitstring.

- Error Model Fitting: Analyze the decay of fidelity with circuit depth to extract average error rates per gate or per layer.

The Mitiq library provides implementations for generating and analyzing mirror circuits [38]:

Protocol 2: PEC Representation Learning

Learning optimal quasiprobability representations is crucial for minimizing sampling overhead:

- Select Basis Operations: Choose a set of physically implementable operations ( {\mathcal{O}_\alpha} ) (typically Pauli gates).

- Characterize Noise Channels: Use quantum process tomography or gate set tomography to reconstruct the actual noise channel ( \Lambda ) for each gate.

- Solve Optimization Problem: Find coefficients ( \eta{i,\alpha} ) that satisfy ( \mathcal{G}i = \sum\alpha \eta{i,\alpha} \mathcal{O}\alpha ) while minimizing ( \gammai = \sum\alpha |\eta{i,\alpha}| ) [38].

- Validate Representation: Verify the accuracy of the representation through randomized benchmarking.

For a depolarizing noise model with error probability ( p ), the inverse channel can be represented using the same gate with error probability ( p/(1-p) ) [35].

Protocol 3: PEC Execution and Estimation

The core PEC protocol combines noisy circuit executions according to the quasiprobability distribution:

- Sample Circuits: For each gate in the original circuit, sample a replacement operation ( \mathcal{O}\alpha ) with probability ( |\eta{i,\alpha}|/\gammai ), keeping track of the sign ( \text{sgn}(\eta{i,\alpha}) ).

- Execute Noisy Circuits: Run each sampled circuit on the quantum processor, measuring the Hamiltonian expectation value.

- Combine Results: Compute the unbiased estimate using the formula: [ \langle H\rangle{\text{PEC}} = \frac{\prodi \gammai}{M} \sum{m=1}^M \text{sgn}m \langle H\ranglem ] where ( M ) is the total number of samples, ( \text{sgn}m ) is the product of signs for the m-th sample, and ( \langle H\ranglem ) is the measurement outcome [38].

The sampling process can be visualized as follows:

Performance Analysis

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Table 3: PEC Performance Across Different Molecular Systems

| Molecular System | Qubit Count | Circuit Depth | Unmitigated Error (mHa) | PEC Error (mHa) | Sampling Overhead |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H₂ (unencoded) | 4 | 10 | >1.6 | ~1.6 | ~10² [3] |

| H₂ (encoded) | 4+ | 15+ | >1.6 | <1.6 | ~10³ [3] |

| Hâ‚‚O | 8-12 | 50-100 | ~10 | ~1.6 | ~10â´ [8] |

| Nâ‚‚ | 12-16 | 100-200 | ~20 | ~1.6 | ~10âµ [8] |

Comparative Analysis with Other Methods

PEC provides theoretical guarantees of unbiased estimation but comes with significant sampling costs. Recent research has explored hybrid approaches that combine PEC with other error mitigation techniques to balance accuracy and overhead:

- PEC + ZNE: Uses zero-noise extrapolation to reduce the number of circuit inversions required while maintaining accuracy [35].

- PEC + CVaR: Applies conditional value at risk to obtain provable bounds on expectation values with lower sampling overhead [39].

- MREM: Multireference error mitigation extends reference-based approaches to strongly correlated systems where traditional PEC might be prohibitively expensive [8].

The binomial PEC approach offers a middle ground by systematically controlling the bias-variance tradeoff [35]. Rather than insisting on completely bias-free estimation, this method allocates shots to different noisy circuits based on their weights, enabling researchers to target biases smaller than the achievable statistical noise.

Application to Quantum Chemistry

Hamiltonian Expectation Values

For quantum chemistry applications, the target observable is typically the molecular Hamiltonian ( H ) expressed as a sum of Pauli operators after the Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev transformation: [ H = \sum{\alpha} h\alpha P\alpha ] where ( P\alpha ) are Pauli operators and ( h_\alpha ) are coefficients determined by the molecular integrals [8].

The PEC protocol estimates each term ( \langle P\alpha \rangle ) independently, though correlated measurement techniques can reduce the total number of measurements required. The final energy estimate is computed as: [ E = \sum{\alpha} h\alpha \langle P\alpha \rangle_{\text{PEC}} ]

Case Study: Water Molecule

Simulating the water molecule requires 8-12 qubits and circuit depths of 50-100 layers depending on the ansatz choice [8]. The multireference error mitigation (MREM) approach, which builds upon PEC principles, has demonstrated significant improvements for this system:

- Reference State Preparation: Prepare a multireference state using Givens rotations to capture strong electron correlations.

- Noise Characterization: Quantify the effect of noise on the reference state through measurement on the quantum device.

- Error Extrapolation: Use the reference state behavior to mitigate errors in the target state simulation.

This approach demonstrates how PEC principles can be adapted to domain-specific challenges in quantum chemistry, particularly for strongly correlated systems where single-reference methods fail [8].

Probabilistic Error Cancellation provides a mathematically rigorous framework for obtaining unbiased estimates of Hamiltonian expectation values on noisy quantum devices. While the sampling overhead presents significant challenges, recent advances in binomial expansion, Pauli error propagation, and hybrid methods have substantially reduced these costs.

For quantum chemistry applications targeting drug development and materials design, PEC enables the calculation of molecular energies with chemical accuracy—a crucial milestone on the path to quantum utility. As quantum hardware continues to improve, with gate errors decreasing and qubit counts increasing, PEC will remain an essential component in the quantum simulation toolbox, potentially bridging the gap between NISQ devices and fault-tolerant quantum computation.

The integration of PEC with problem-specific approaches like multireference error mitigation demonstrates how domain knowledge can be leveraged to enhance error mitigation efficacy. This synergy between general-purpose quantum error mitigation and application-specific optimizations will likely drive further improvements in computational accuracy for quantum chemistry simulations.

Clifford Data Regression (CDR) is a learning-based quantum error mitigation technique designed to enhance the accuracy of expectation values obtained from noisy quantum computations. It is particularly vital for the execution of variational quantum algorithms on Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) hardware, where gate and decoherence noise significantly corrupt results without the resource overhead of full quantum error correction [40] [41]. The core principle of CDR is to leverage the fact that quantum circuits composed predominantly of Clifford gates can be efficiently simulated on classical computers, as per the Gottesman-Knill theorem [40] [8]. CDR operates by training a regression model on a set of "near-Clifford" training circuits. For these circuits, both the ideal (noise-free) expectation values and their noisy counterparts from quantum hardware can be obtained. The model learns the functional relationship between noisy and ideal outputs, and this learned mapping is then applied to mitigate errors in the far more complex, non-Clifford target circuit of interest [40] [41].

The utility of CDR is acutely demonstrated in quantum chemistry simulations, such as those performed with the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) to find molecular ground state energies. For these problems, which are beyond exact classical simulation for large systems, CDR offers a pathway to more reliable results without prohibitive sampling overheads [40]. This protocol details the application of CDR and its enhanced variants within the context of near-term quantum chemistry research.

Theoretical Foundation and Protocol Enhancements

Core CDR Methodology

The CDR protocol begins with the identification of a target circuit, such as a VQE ansatz (e.g., the tiled Unitary Product State or tUPS) for a molecule like H₄, which contains a non-trivial number of non-Clifford gates [40]. The goal is to mitigate the noise in the expectation value of the molecular Hamiltonian, ⟨H⟩, measured from this circuit.

The foundational CDR workflow involves several key steps [40] [41]:

- Generate Training Circuits: Create a set of classically simulable training circuits that structurally resemble the target circuit. This is typically done by replacing most, but not all, of the non-Clifford gates in the target circuit with Clifford gates.

- Compute Ideal Values: Use efficient classical Clifford simulators to calculate the exact, noise-free expectation values for the observable of interest for each training circuit.

- Collect Noisy Data: Execute the same set of training circuits on the noisy quantum processor (or a high-fidelity noise model simulator) to obtain the corresponding noisy expectation values.

- Train Regression Model: Using the paired data (noisy value, ideal value), train a simple linear regression model. The model learns a mapping ( f ) such that ( \text{ideal} \approx f(\text{noisy}) ).

- Mitigate Target Circuit: Execute the target non-Clifford circuit on the quantum device to get a noisy expectation value. Apply the trained regression model to this value to obtain the error-mitigated estimate.

Enhanced CDR Protocols

Recent research has introduced significant improvements to the core CDR protocol, enhancing its accuracy and efficiency for chemistry simulations. Two notable enhancements are Energy Sampling and Non-Clifford Extrapolation [40].

- Energy Sampling (ES): This improvement addresses the quality of training data. Instead of using all generated training circuits, the ES protocol filters them based on their noiseless energy. Only the training circuits whose ideal energies are closest to the (estimated) ground state energy of the target molecule are selected for regression. This biases the learning process towards circuits whose quantum states are more physically relevant, improving the accuracy of the noise mapping for the target state [40].

- Non-Clifford Extrapolation (NCE): This enhancement improves the regression model itself. The standard CDR uses a single input feature—the noisy expectation value. The NCE protocol incorporates an additional input feature: the number of non-Clifford parameters in the training circuit. This allows the model to learn how the noisy-ideal relationship evolves as the circuit's structure approaches that of the target circuit, effectively enabling an extrapolation in "non-Cliffordness" [40].

Table 1: Key Enhancements to Clifford Data Regression

| Protocol | Core Idea | Application in Chemistry Simulations | Key Benefit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard CDR [41] | Linear regression on noisy vs. ideal data from near-Clifford circuits. | Mitigating energy measurements in VQE for small molecules. | Reduces bias from noise without full error correction. |

| Energy Sampling (ES) [40] | Selects training circuits with energies near the target ground state. | Focusing mitigation on chemically relevant states in Hâ‚„ simulations. | Improves model accuracy by using physically meaningful training data. |

| Non-Clifford Extrapolation (NCE) [40] | Uses the number of non-Clifford gates as an additional regression feature. | Capturing how noise effects change with ansatz complexity in tUPS. | Enables better generalization from Clifford-dominated to target circuits. |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Detailed Protocol for Enhanced CDR in VQE

This protocol outlines the steps for applying Energy Sampling and Non-Clifford Extrapolation to mitigate errors in a VQE energy calculation.