Quantum Mechanics of Chemical Bonding: From Fundamental Theory to Advanced Drug Discovery Applications

This comprehensive review elucidates the quantum mechanical principles governing chemical bond formation, bridging fundamental theory with practical applications in pharmaceutical research.

Quantum Mechanics of Chemical Bonding: From Fundamental Theory to Advanced Drug Discovery Applications

Abstract

This comprehensive review elucidates the quantum mechanical principles governing chemical bond formation, bridging fundamental theory with practical applications in pharmaceutical research. It explores foundational concepts including wavefunction delocalization, kinetic-potential energy balance, and Pauli exclusion effects, contrasting historical models with contemporary quantum chemical analyses. The article critically evaluates computational methodologies—from ab initio and DFT to hybrid QM/MM schemes—detailing their implementation in drug-design workflows for predicting binding affinities, modeling reaction mechanisms, and optimizing lead compounds. It further addresses methodological limitations and optimization strategies for complex biological systems, while presenting validation frameworks and comparative performance assessments across different bonding types and molecular classes. Synthesizing these perspectives provides researchers with a unified conceptual and practical framework for leveraging quantum mechanics in rational drug design and biomolecular innovation.

Quantum Foundations of Chemical Bonding: Beyond Lewis Structures to Electron Delocalization

The application of quantum mechanics to chemistry represents one of the most significant paradigm shifts in modern science, providing a physical understanding of the chemical bond that had previously been purely empirical. Quantum chemistry, also called molecular quantum mechanics, is a branch of physical chemistry focused on the application of quantum mechanics to chemical systems, particularly towards the quantum-mechanical calculation of electronic contributions to physical and chemical properties of molecules, materials, and solutions at the atomic level [1]. This field has evolved from the first tentative quantum descriptions of the hydrogen molecule to sophisticated computational methods that can predict molecular structure, reactivity, and properties with remarkable accuracy. The historical progression from the Heitler-London model to modern computational approaches reflects both conceptual advances and the development of powerful computational methodologies that have transformed theoretical chemistry into a predictive science. This evolution is particularly relevant to drug development professionals who rely on computational predictions of molecular behavior, binding affinity, and reactivity in the design of novel therapeutic agents.

The Heitler-London Model: Foundation of Quantum Chemistry

The Seminal 1927 Paper

The birth of quantum chemistry is often traced to the seminal 1927 paper by Walter Heitler and Fritz London, which provided the first quantum-mechanical treatment of the hydrogen molecule and thus the first physical explanation for the phenomenon of the chemical bond [1] [2]. This work marked a fundamental departure from classical conceptions of bonding and established the conceptual framework for understanding covalent bonds. Heitler and London's approach was groundbreaking because it demonstrated how quantum mechanics could quantitatively account for chemical bonding, specifically explaining why two hydrogen atoms would form a stable Hâ‚‚ molecule rather than remain as separate atoms.

The Heitler-London model focused on the simplest possible chemical system—the hydrogen molecule—comprising two protons and two electrons. Within the Born-Oppenheimer approximation, which decouples the motions of electrons and protons due to their large mass difference, the electronic Hamiltonian for H₂ can be written in atomic units as [2]:

Where the terms represent, from left to right: the kinetic energies of the electrons, the attractive potentials between electrons and protons, and the repulsive electron-electron and proton-proton potentials.

Wave Function and Bonding Mechanism

The key insight of Heitler and London was to express the molecular wave function as a linear combination of products of atomic orbitals. For the hydrogen molecule, they proposed the wave function [2]:

Here, ϕ(rij) = √(1/π) e^(-rij) represents the ground-state 1s orbital of an isolated hydrogen atom, and N± is the normalization constant for the symmetric (+) and antisymmetric (-) combinations. The symmetric combination (ψ+) corresponds to the singlet spin state with lower energy (bonding orbital), while the antisymmetric combination (ψ-) corresponds to the triplet spin state with higher energy (antibonding orbital).

This approach successfully explained the covalent bond through the quantum mechanical effects of electron sharing and spin pairing, demonstrating that the energy lowering in the bonding state resulted from the accumulation of electron density between the two nuclei. The model qualitatively explained the physical mechanism of covalent bond formation, distinguishing between the physical reality of the quantum mechanical interaction and the heuristic models chemists had previously developed in the absence of a physical basis for understanding the chemical bond [3].

Methodological Framework and Experimental Validation

The Heitler-London approach established the valence-bond (VB) method, which was subsequently extended by Slater and Pauling [1]. This method focuses on pairwise interactions between atoms and correlates closely with classical chemists' drawings of bonds, incorporating the key concepts of orbital hybridization and resonance. The valence-bond theory dominated early quantum chemistry and was successfully explained in Linus Pauling's highly influential 1939 text The Nature of the Chemical Bond and the Structure of Molecules and Crystals, which made quantum mechanics accessible to chemists and became a standard university text [1].

Table 1: Key Developments in Early Quantum Chemistry (1927-1939)

| Year | Researcher(s) | Contribution | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1927 | Heitler & London | First quantum mechanical treatment of Hâ‚‚ molecule | Provided physical explanation for covalent bond |

| 1928-1930 | Hund, Mulliken | Molecular orbital theory | Alternative approach with delocalized orbitals |

| 1930s | Pauling | Development of valence bond theory | Integrated quantum mechanics with chemical bonding concepts |

| 1939 | Pauling | The Nature of the Chemical Bond | Made quantum chemistry accessible to chemists |

The Heitler-London model represented a variational method that provided an approximate solution to the Schrödinger equation for molecules. Although limited to small systems due to computational complexity, it established the fundamental principle that chemical bonding could be understood through the quantum mechanical behavior of electrons. Recent research has revisited this foundational approach, with a 2025 study proposing modifications to the original HL wave function to include electronic screening effects, demonstrating how this early model continues to inspire contemporary research [2].

Theoretical Advances: From Valence Bond to Molecular Orbital Theory

The Molecular Orbital Alternative

In 1929, shortly after the development of the valence-bond approach, Friedrich Hund and Robert S. Mulliken proposed an alternative conceptual framework known as molecular orbital (MO) theory [1]. This approach represented a fundamental shift in perspective: rather than focusing on pairwise interactions between atoms, the MO method described electrons by mathematical functions delocalized over the entire molecule. While less intuitive to chemists accustomed to thinking in terms of localized bonds, molecular orbital theory proved particularly powerful for predicting spectroscopic properties and eventually became the dominant paradigm in quantum chemistry.

The molecular orbital approach forms the conceptual basis of the Hartree-Fock method, which represents the starting point for most modern quantum chemical calculations. In the Hartree-Fock approach, each electron is assumed to move in an average field created by all the other electrons, and the molecular orbitals are constructed as linear combinations of atomic orbitals (LCAO). This method provided a more systematic approach for extending quantum chemical calculations to larger molecules, though it initially faced challenges in accurately describing chemical bonding.

Density Functional Theory

A fundamentally different approach emerged from the Thomas-Fermi model developed in 1927, which represented the first attempt to describe many-electron systems based on electronic density rather than wave functions [1]. Although not initially successful for treating entire molecules, this approach provided the foundation for what is now known as density functional theory (DFT). Modern DFT uses the Kohn-Sham method, where the density functional is split into four terms: the Kohn-Sham kinetic energy, an external potential, and exchange and correlation energies.

DFT has become one of the most popular methods in computational chemistry due to its significantly lower computational requirements compared to post-Hartree-Fock methods (typically scaling no worse than n³ with respect to n basis functions for pure functionals) while often achieving comparable accuracy to MP2 and CCSD(T) methods [1]. This computational affordability has made DFT particularly valuable for studying large polyatomic molecules and macromolecules relevant to pharmaceutical research and materials science.

Advanced Computational Methods

The evolution of quantum chemistry has been marked by the development of increasingly sophisticated computational methods to address the limitations of earlier approaches:

- Post-Hartree-Fock Methods: These include configuration interaction (CI), coupled cluster (CC) theory, and Møller-Plesset perturbation theory, which account for electron correlation neglected in the basic Hartree-Fock method.

- Quantum Monte Carlo Methods: These stochastic approaches, including variational quantum Monte Carlo (VQMC) used in recent revisitations of the HL model [2], provide accurate treatment of electron correlation.

- Multiconfigurational Methods: Techniques such as complete active space SCF (CASSCF) are used to describe systems with significant static correlation.

Table 2: Comparison of Major Quantum Chemical Methods

| Method | Theoretical Basis | Scaling with System Size | Key Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valence Bond | Linear combination of atomic orbitals | Very expensive | Chemically intuitive, accurate for bonds | Poor scaling, limited to small systems |

| Hartree-Fock | Molecular orbitals as LCAO | Nâ´ | Systematic, fundamental for later methods | Neglects electron correlation |

| Density Functional Theory | Electron density | N³ to Nⴠ| Good accuracy/cost ratio for large systems | Functional choice critical, challenges with dispersion |

| Coupled Cluster | Exponential wave function ansatz | Nâ· for CCSD(T) | "Gold standard" for small molecules | Very computationally expensive |

| Quantum Monte Carlo | Stochastic sampling | N³ to Nⴠ| Accurate correlation treatment, parallelizable | Statistical uncertainty, fixed-node error |

Recent work has highlighted how these advanced methods build upon the conceptual foundation laid by the Heitler-London approach. For instance, a 2025 study employed variational quantum Monte Carlo calculations using the HL wave function modified by a single variational parameter representing an effective nuclear charge, demonstrating how the original model can be enhanced with modern computational techniques [2].

Quantitative Comparison of Methodologies

Accuracy and Computational Efficiency

The evolution of quantum chemical methods can be traced through systematic improvements in both accuracy and computational efficiency. Quantitative comparison between different computational paradigms remains essential for selecting appropriate methods for specific applications [4]. Early quantum chemical calculations were limited to small molecules with high symmetry, but methodological advances have progressively expanded the range of accessible systems.

The development of density functional theory represents a particularly important advancement in terms of balancing accuracy and computational cost. Unlike wave function-based methods that explicitly consider the complex many-electron wave function, DFT focuses on the electron density—a simpler physical observable—while still in principle containing complete information about the system (according to the Hohenberg-Kohn theorems). This conceptual shift enabled calculations on larger systems that would be prohibitively expensive with wave function-based methods.

Performance on Chemical Properties

Different quantum chemical methods show varying performance in predicting specific chemical properties. The table below summarizes key benchmarks for common methodologies:

Table 3: Performance of Quantum Chemical Methods for Key Properties

| Method | Bond Lengths | Bond Energies | Reaction Barriers | Spectroscopic Properties | Non-covalent Interactions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hartree-Fock | Underestimated by 1-2% | Poor (30-50% error) | Poor | Reasonable frequencies, poor intensities | Very poor |

| MP2 | Good (1-2% error) | Good (5-10% error) | Variable | Generally good | Reasonable but overbinding |

| DFT (B3LYP) | Good (1-2% error) | Good (5-10% error) | Variable (underestimation common) | Generally good | Poor without correction |

| CCSD(T) | Excellent (<1% error) | Excellent (1-3% error) | Good to excellent | Excellent | Good with large basis sets |

| Experiment | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

The original Heitler-London model, while qualitatively correct, showed significant quantitative limitations. For the Hâ‚‚ molecule, it predicted a bond length of 0.80 Ã… (compared to the experimental value of 0.74 Ã…) and a binding energy of 3.14 eV (versus the experimental 4.75 eV) [2]. Modern approaches have dramatically improved upon these initial results while retaining the fundamental physical insights of the early model.

Quantitative Comparison Protocols

Rigorous quantitative comparison between computational methods requires standardized protocols and benchmarks. The DIFFENERGY method, introduced by Smith et al., provides one approach for quantitative comparison in the frequency domain [4]. This method involves:

- Starting with a high-quality reference data set

- Artificially truncating the data to simulate limitations

- Applying different reconstruction/modeling algorithms

- Comparing the results with the original reference data

Such quantitative comparisons are essential for evaluating the success of modeling algorithms beyond the "ugly picture before - pretty picture now" criterion that has historically dominated the field [4]. For drug development applications, standardized benchmarks for predicting binding affinities, reaction barriers, and spectroscopic properties are particularly valuable.

Experimental Protocols and Computational Methodologies

Variational Quantum Monte Carlo for Hâ‚‚

Recent revisitations of the Heitler-London model have employed sophisticated computational methodologies to improve upon the original approach. The 2025 study by researchers from Brazilian institutions implemented a variational quantum Monte Carlo (VQMC) protocol using the HL wave function modified with an effective nuclear charge parameter [2]. The experimental protocol involved:

Wave Function Preparation: Using a screening-modified HL wave function: ψ(r→â‚, r→₂) = N[Ï•(αrâ‚A)Ï•(αrâ‚‚B) + Ï•(αrâ‚B)Ï•(αrâ‚‚A)], where α is the variational parameter representing effective nuclear charge.

Parameter Optimization: Systematically varying α to minimize the energy expectation value for each internuclear distance R.

Energy Calculation: Computing the total energy as a function of R using the variational principle.

Property Extraction: Determining the bond length, binding energy, and vibrational frequency from the resulting potential energy curve.

This approach demonstrated how incorporating electronic screening effects into the original HL wave function could substantially improve agreement with experimental values, particularly for the bond length of Hâ‚‚ [2].

Kinetic Isotope Effect Analysis

For complex chemical reactions, kinetic isotope effect (KIE) analysis provides detailed experimental constraints on reaction mechanisms and transition states. A sophisticated protocol for KIE analysis was employed in studies of ribosome-catalyzed peptide bond formation [5], which has relevance for understanding fundamental biochemical processes:

Substrate Preparation: Synthesis of a complete series of molecules differing by a single isotopic substitution at each atom within the reaction center.

Competitive Assay: Incubating light and heavy substrates in the same reaction and monitoring the change in their ratio as the reaction proceeds.

Dual Radiolabel Detection: Using two remote radiolabels (³²P and ³³P) attached to the 5'-ends of the P-site substrate and performing scintillation counting to define relative abundance.

Control Experiments: Performing multiple control measurements to account for random and systematic errors, including reverse pairings of radiolabels with light/heavy isotopes.

This approach allowed researchers to measure isotope effects at five different positions in the reaction center, providing detailed information about bond formation and breaking in the transition state [5]. Such methodologies illustrate the sophisticated experimental techniques now available for validating computational predictions.

Quantum Chemical Topology Analysis

Advanced analysis methods such as quantum chemical topology of electron density provide insights into bonding changes during chemical reactions. The experimental protocol for these analyses typically involves [6]:

Geometry Optimization: Determining minimum energy paths and transition state structures using computational methods such as DFT.

Electron Localization Function (ELF) Analysis: Topological analysis of the ELF to understand bonding changes.

Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate (IRC) Calculations: Tracing the minimum energy path from transition states to reactants and products.

Bond Evolution Analysis: Monitoring the evolution of chemical bonds throughout the reaction pathway.

These methods have led to new models of bond formation, such as the proposal that C-C bond formation occurs through "coupling of two pseudoradical centers" [6], challenging earlier frontier molecular orbital theories.

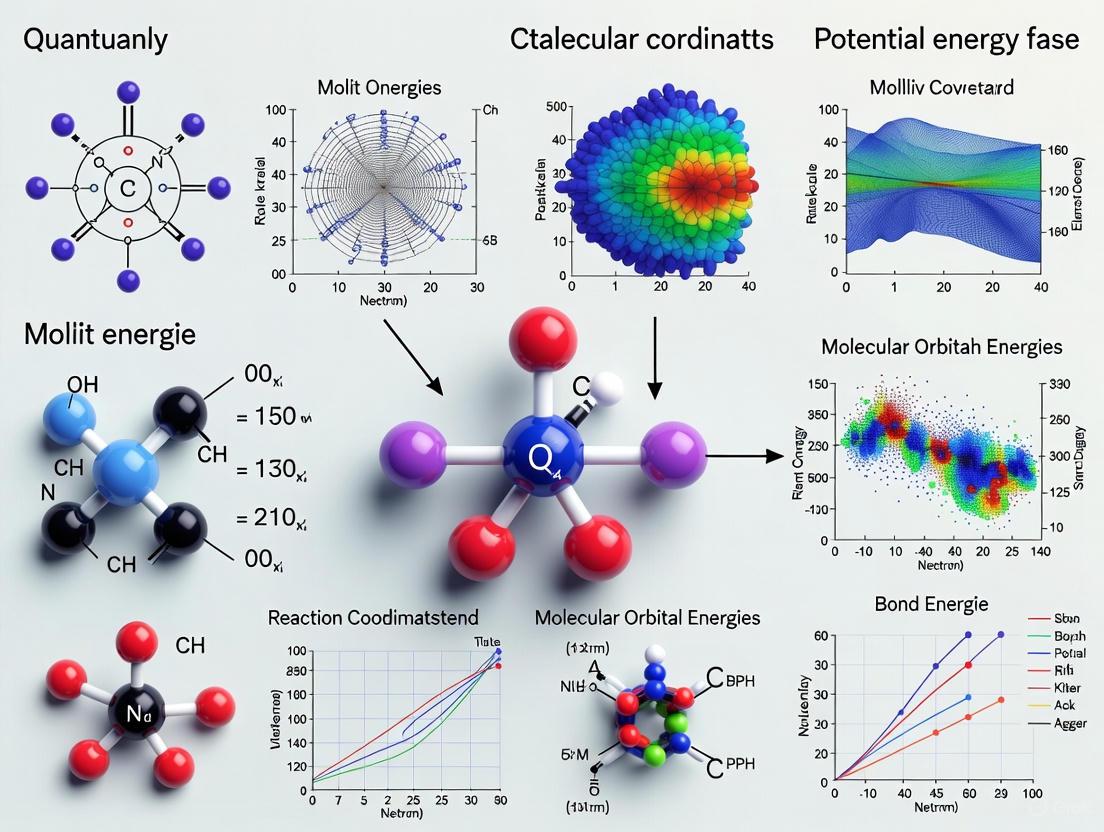

Visualization of Theoretical Relationships and Computational Workflows

Historical Evolution of Quantum Chemical Models

Figure 1: Historical development of quantum chemical models from classical concepts to modern computational methods, highlighting the foundational role of the Heitler-London approach.

Computational Workflow for Modern Quantum Chemistry

Figure 2: Typical computational workflow in modern quantum chemistry studies, showing the sequence from system definition through calculation to analysis.

Computational Methods and Software

Table 4: Essential Computational Tools in Modern Quantum Chemistry

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Applications in Bond Formation Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electronic Structure Packages | Gaussian, GAMESS, ORCA, Q-Chem | Perform quantum chemical calculations | Energy computation, geometry optimization, property prediction |

| Wave Function Analysis | Multiwfn, AIMAll, NBO | Analyze computational results | Bond order calculation, electron density analysis, orbital visualization |

| Molecular Visualization | VMD, Chimera, GaussView | Visualize molecular structures and properties | Structure rendering, orbital visualization, reaction pathway animation |

| Specialized Methods | VQMC (Variational Quantum Monte Carlo) [2] | High-accuracy electron correlation | Benchmark studies, small molecule precision calculations |

| Topology Analysis | ELF (Electron Localization Function) analysis [6] | Study chemical bonding | Bond formation analysis, reaction mechanism elucidation |

Theoretical Models and Analysis Techniques

Table 5: Key Theoretical Frameworks and Analysis Methods

| Theoretical Framework | Key Components | Research Applications | Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heitler-London Model | Linear combination of atomic orbitals, electron sharing concept | Foundation for valence bond theory, conceptual understanding | Physical intuition, fundamental principles |

| Molecular Orbital Theory | Delocalized orbitals, LCAO approximation, symmetry adaptation | Spectroscopy, aromatic systems, extended molecules | Systematic approach, predictive power for properties |

| Density Functional Theory | Electron density, exchange-correlation functionals, Kohn-Sham equations | Large systems, materials science, catalysis | Favorable accuracy/cost ratio for many applications |

| Kinetic Isotope Effects [5] | Isotopic substitution, competitive assays, transition state analysis | Reaction mechanism elucidation, enzyme catalysis | Detailed transition state information, experimental validation |

| Quantum Chemical Topology [6] | Electron density analysis, bond critical points, ELF analysis | Bond formation mechanisms, reaction pathways | Detailed bonding information, beyond orbital concepts |

The historical evolution from the Heitler-London model to modern quantum chemical approaches represents one of the most successful trajectories in theoretical chemistry. What began as a qualitative explanation for the covalent bond in the hydrogen molecule has developed into a sophisticated computational framework capable of predicting molecular structure, reactivity, and properties with remarkable accuracy. This evolution has been characterized by both conceptual advances—from valence bond to molecular orbital theory to density functional theory—and methodological improvements driven by increases in computational power and algorithmic efficiency.

For contemporary researchers and drug development professionals, modern quantum chemistry offers powerful tools for understanding and predicting molecular behavior. The field continues to advance through improvements in existing methods, development of new approaches such of machine learning potentials, and more accurate treatment of complex phenomena such as non-covalent interactions, excited states, and solvent effects. The recent revisitation of the Heitler-London model with advanced computational techniques [2] demonstrates how foundational concepts continue to inform and inspire current research, creating a rich dialogue between the historical roots of quantum chemistry and its cutting-edge applications.

As quantum chemistry moves forward, several challenges remain: increasing the accuracy of results for small molecular systems, expanding the size of molecules that can be realistically subjected to computation (which is limited by scaling considerations), and better integrating quantum chemical insights with experimental observations. Nevertheless, the progression from Heitler and London's pioneering work to today's sophisticated computational methods stands as a testament to the power of theoretical models to illuminate the fundamental nature of chemical bonding and to enable practical advances in fields ranging from materials science to drug discovery.

Wavefunction Delocalization and Constructive Quantum Interference as Bonding Origins

The quantum mechanical description of the chemical bond has evolved significantly from classical electrostatic explanations to a nuanced understanding grounded in wavefunction delocalization and constructive quantum interference. While the virial theorem correctly describes the energy balance at equilibrium, the primary driving force for covalent bond formation is the kinetic energy lowering achieved through electron delocalization across atomic centers. This whitepaper synthesizes current research demonstrating how constructive interference between atomic wavefunctions enables electron sharing, supported by experimental evidence from single-molecule junctions and theoretical advances in real-space wavefunction analysis. We present quantitative data from key studies, detailed experimental methodologies, and computational protocols that together establish a comprehensive framework for understanding bonding origins, with particular relevance to molecular design in materials science and drug development.

The fundamental question of why atoms bind covalently has been resolved through quantum mechanics, moving beyond Lewis's electron pair concept to a wave-based understanding of interference phenomena. The chemical bond originates from the quantum mechanical requirement that electron wavefunctions be antisymmetric under particle exchange, leading to constructive interference patterns that lower kinetic energy through delocalization [7]. Early work by Heitler and London on the H₂ molecule first revealed this "Schwebungsphänomen" (interference phenomenon), establishing that atomic wavefunctions interfere—this interference constitutes the essence of covalent bonding between atoms [8]. The Born-Oppenheimer approximation provides the foundational framework by separating nuclear and electronic motions, enabling the calculation of molecular potential energy curves where energy minima correspond to stable bond configurations [9].

The historical debate between electrostatic (Slater, Feynman) and kinetic (Hellmann, Ruedenberg) explanations of bonding has largely been resolved in favor of the latter, though with important nuances revealed by modern analysis methods [10] [11]. While the virial theorem correctly states that at equilibrium geometry, potential energy decreases twice as much as the kinetic energy increases, the initial driving force for bond formation is the kinetic energy lowering through delocalization, which creates a virial imbalance subsequently corrected by orbital contraction [10]. This paper synthesizes evidence from multiple contemporary studies to establish a unified understanding of wavefunction delocalization and constructive quantum interference as the primary origins of covalent bonding.

Theoretical Foundations: From Interference to Bond Formation

The Role of Constructive Quantum Interference

Constructive quantum interference occurs when atomic wavefunctions combine with the same phase, creating enhanced amplitude in the internuclear region. This interference pattern allows electrons to delocalize over multiple atomic centers, reducing their kinetic energy by expanding their effective confinement region—analogous to a particle in a larger box [7]. The valence bond (VB) description formalizes this concept through the resonance between covalent and ionic terms, where the resonance stabilization energy directly correlates with reduced probabilistic barriers to electron movement between atomic centers [7]. In molecular orbital theory, this corresponds to the formation of bonding orbitals with enhanced internuclear electron density and no nodal planes between bonded atoms.

The connection between interference and bond formation has been directly demonstrated in single-molecule junctions, where para-connected benzene derivatives exhibit conductance approximately one order of magnitude higher than meta-connected analogues due to constructive versus destructive quantum interference in the π-system [12]. Extended π-conjugation in meta-connected molecules further suppresses conductance, indicating that enhanced π-electron delocalization amplifies destructive interference effects—a clear signature of the wave nature of electrons in bonding [12].

The Kinetic Energy Perspective on Bond Formation

Ruedenberg's seminal analysis of H₂⺠and H₂ established that roughly 66% of the binding energy comes from constructive quantum interference that lowers kinetic energy by delocalizing electrons across both centers [10]. This delocalization creates a virial imbalance that triggers a secondary orbital contraction effect, where orbitals contract toward nuclei, lowering potential energy while raising kinetic energy [10]. The net effect is the energy minimization described by the virial theorem, but the initial driving force remains kinetic.

However, recent work has revealed that this mechanism is not universal across all bonds. For molecules between heavier elements (e.g., H₃C–CH₃, F–F), the kinetic energy often increases during bond formation due to Pauli repulsion between bonding electrons and core electrons [10]. This finding highlights the fundamental role of constructive quantum interference as the unifying origin of chemical bonding, with differences between interfering states distinguishing one bond type from another.

Table 1: Kinetic and Potential Energy Changes During Bond Formation for Selected Molecules

| Molecule | ΔEₜₒₜ (kcal/mol) | ΔT (kcal/mol) | ΔV (kcal/mol) | Primary Bonding Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H₂⺠| -64.0 | -42.2 | -21.8 | KE lowering via delocalization |

| Hâ‚‚ | -109.3 | -72.1 | -37.2 | KE lowering via delocalization |

| H₃C–CH₃ | -90.2 | +15.4 | -105.6 | PE lowering with Pauli repulsion |

| F–F | -38.5 | +22.8 | -61.3 | PE lowering with Pauli repulsion |

| H₃C–SiH₃ | -75.6 | +18.3 | -93.9 | PE lowering with Pauli repulsion |

Real-Space Analysis of Electron Delocalization

Probability density analysis (PDA) provides a real-space perspective on delocalization by examining the local maxima of |Ψ|² (structure critical points, SCPs) and the saddle points between them (delocalization critical points, DCPs) [7]. In H₂, four SCPs correspond to covalent and ionic electron arrangements, while DCPs represent paths for electron exchange between these arrangements. The probabilistic barrier between covalent SCPs is minimized at optimal resonance mixing, consistent with the view that electrons in the Hartree-Fock description of H₂ are completely delocalized [7].

This real-space approach generalizes Hückel's 4n+2 rule for aromaticity from nothing but the antisymmetry of fermionic wavefunctions, deriving aromatic stabilization from the increased freedom of electron movement in cyclic systems [7]. The approach also explains Baird's rule inversion for triplet systems, where 4n π-electron systems become aromatic, through modified interference patterns in excited states.

Figure 1: Quantum Interference Pathway to Bond Formation. Constructive interference between atomic wavefunctions leads to bonding orbital formation, kinetic energy lowering, and electron delocalization, ultimately resulting in covalent bond formation.

Experimental Evidence and Methodologies

Single-Molecule Conductance Measurements

Break-junction techniques provide direct experimental validation of quantum interference effects in bonding. In studies of para- and meta-connected dipyridylbenzene derivatives, conductance measurements reveal the dramatic impact of quantum interference on electron transport [12]:

Experimental Protocol:

- Molecular Synthesis: Para- and meta-connected dipyridylbenzene derivatives are synthesized with varying π-conjugation lengths

- Break-Junction Formation: A metallic junction is mechanically stretched in solution containing target molecules until rupture occurs at the atomic scale

- Conductance Measurement: As electrodes separate, molecular bridges form spontaneously, allowing current-voltage measurements across single molecules

- Statistical Analysis: Thousands of breaking cycles generate conductance histograms to determine most probable conductance values

- Theoretical Validation: Density functional theory–non-equilibrium Green's function (DFT–NEGF) calculations model the electronic structure and quantum interference effects

Key Findings:

- Para-connected molecules exhibit conductance approximately one order of magnitude higher than meta-connected counterparts

- Extended π-conjugation in meta-connected molecules further suppresses conductance

- DFT–NEGF calculations confirm constructive interference in para-connected systems versus destructive interference in meta-connected systems

Table 2: Conductance Measurements of Benzene Derivatives Demonstrating Quantum Interference Effects

| Molecule Structure | Connection Type | π-Conjugation Length | Relative Conductance | Interference Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dipyridylbenzene | para | Short | 1.00 | Constructive |

| Dipyridylbenzene | meta | Short | 0.12 | Destructive |

| Extended Derivative 1 | para | Medium | 1.35 | Constructive |

| Extended Derivative 1 | meta | Medium | 0.08 | Destructive |

| Extended Derivative 2 | para | Long | 1.52 | Constructive |

| Extended Derivative 2 | meta | Long | 0.05 | Destructive |

Orbital Imaging via Scanning Tunneling Microscopy

Advanced scanning tunneling microscopy (STM) techniques directly visualize the nodal structure of molecular orbitals, providing unprecedented experimental validation of quantum interference in chemical bonds [13]:

Experimental Protocol:

- Tip Functionalization: A metallic STM tip is functionalized with a carbon monoxide (CO) molecule positioned upright at the apex through voltage-controlled attachment

- Substrate Preparation: A clean metal surface is covered with a double layer of NaCl to electronically decouple adsorbed molecules from the substrate

- Molecular Deposition: Flat organic molecules (e.g., pentacene) are deposited onto the insulated substrate

- Orbital Imaging: The CO-functionalized tip scans across molecules with voltage tuned to address specific molecular orbitals

- Phase-Sensitive Detection: Interference between the CO frontier orbitals and molecular orbitals reveals nodal structure through registry variations

Key Findings:

- CO-functionalized tips resolve positive and negative lobes of molecular orbitals

- Nodal planes appear as regions of zero signal between lobes of opposite phase

- Technique directly images orbital geometry that governs chemical properties and intermolecular interactions

Figure 2: STM Orbital Imaging Workflow. CO-functionalized tips with insulated substrates enable phase-sensitive detection of molecular orbitals through quantum interference effects.

Computational Methodologies for Bonding Analysis

Wavefunction Theory Methods

Advanced computational methods enable precise quantification of delocalization and interference effects in chemical bonding:

Single-Reference Methods: Coupled cluster (CC) methods, particularly CCSD(T), represent the "gold standard" for accuracy in quantum chemistry when a single Slater determinant provides a reasonable reference state [14]. The CCSD(T) method with full iterative treatment of singles and doubles and perturbational treatment of triples provides reliable results even for transition metal complexes with moderate nondynamical correlation effects [14].

Multireference Methods: For systems with strong static correlation, multireference methods based on complete active space self-consistent field (CASSCF) wavefunctions provide the most accurate description [14]. Subsequent calculations with multireference configuration interaction (MRCI) or second-order perturbation theory (CASPT2, NEVPT2) capture dynamic correlation effects. The critical aspect is active space selection, typically including metal d orbitals with correlating d' orbitals and ligand orbitals for transition metal complexes [14].

Explicitly Correlated Methods: CCSD(T)-F12 methods incorporate interelectronic distance directly into the wavefunction, drastically improving convergence to the complete basis set limit [14]. These methods provide reasonably small basis set incompleteness error even with triple-ζ quality basis sets, offering an optimal balance between accuracy and computational cost [14].

Energy Decomposition Analysis

The Absolutely Localized Molecular Orbital Energy Decomposition Analysis (ALMO-EDA) method decomposes the total interaction energy into physically meaningful components along the bond-forming path [10]:

Methodology:

- Energy Preparation (ΔEPrₑₚ): Fragments are distorted from isolated geometries to molecular configurations

- Covalent Interaction (ΔECₒᵥ): Constructive quantum interference between prepared fragment wavefunctions with fixed orbitals

- Orbital Contraction (ΔECₒₙ): Energy lowering from orbital contraction toward nuclei

- Polarization & Charge Transfer (ΔEPCₜ): Remaining stabilization from bond polarization and charge transfer

Key Insights:

- For H₂, ΔECₒᵥ shows significant kinetic energy lowering from delocalization

- For bonds between heavier atoms (C–C, F–F), ΔECₒᵥ often shows kinetic energy increase due to Pauli repulsion with core electrons

- Orbital contraction (ΔECₒₙ) is significant for H-containing bonds but minimal for bonds between heavier atoms

The Tribasis Method for Delocalization Analysis

The tribasis method rigorously defines delocalization effects by reconstructing traditional atomic basis sets into strictly localized atomic orbitals and interatomic bridge functions [11]:

Methodology:

- Local Orbital Construction: From two atomic orbitals, create ground and excited diatomic orbitals, then extract local atomic orbitals by cutting at the bond mid-plane node

- Bridge Function Formation: Project local states out of the symmetric combination to create a bridge function enabling interatomic electron motion

- Energy Comparison: Compute energy differences between systems with and without bridge functions to quantify "dynamical delocalization energy"

Applications:

- For H₂⺠and H₂, the method recovers minimal basis results while precisely quantifying delocalization stabilization

- Reconstructs Hückel theory for π-systems while resolving the overlap problem

- Reveals bonding as a balance between Pauli repulsion of localization and stronger delocalization stabilization

Research Reagent Solutions: Computational Tools for Bonding Analysis

Table 3: Essential Software Tools for Wavefunction and Bonding Analysis

| Software Tool | License Type | Key Capabilities | Bonding Analysis Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| LOBSTER | Free for academics | Periodic bonding analysis | Crystal Orbital Overlap Population (COOP), bond orders, density-of-energy partitioning |

| Chemcraft | Commercial (academic discounts) | Visualization | Molecular orbital visualization, vibrational spectra, population analysis |

| ORCA | Free for academics | Wavefunction theory | CCSD(T), CASSCF, EDA, spectroscopic properties |

| Q-Chem | Commercial | Advanced DFT/WFT | Absolutely Localized EDA, orbital analysis, response properties |

| GAMESS | Free for academics | Ab initio methods | VB theory, MRCI, EDA, spectral simulation |

| Gaussian | Commercial | General quantum chemistry | NBO analysis, AIM, excited states, solvent effects |

| ADF/AMS | Commercial | DFT modeling | EDA, COOP, bonding analysis, spectroscopy |

| CP2K | Open source | Solid-state/ molecular | Hybrid DFT, molecular dynamics, energy decomposition |

Implications for Molecular Design in Pharmaceutical Research

The principles of wavefunction delocalization and quantum interference provide powerful design tools for drug development professionals:

Aromaticity in Drug Design: Hückel's rule generalized through antisymmetry requirements explains the exceptional stability of aromatic systems common in pharmaceutical compounds [7]. The 4n+2 electron count creates continuous delocalization pathways with minimal probabilistic barriers, enhancing stability and influencing binding interactions.

Intermolecular Interactions: Quantum interference patterns control molecular recognition processes in drug-receptor interactions. Complementary interference between ligand and protein orbitals can enhance binding affinity through constructive interference, while mismatched phases reduce affinity [13].

Conjugated System Engineering: Extended π-conjugation in drug molecules can be optimized to balance delocalization effects with specific binding requirements. Meta-substitutions in aromatic systems can strategically suppress delocalization to modulate electronic properties without compromising structural integrity [12].

Solvent Effects: Dielectric environments modify quantum interference patterns through screening effects, explaining solvent-dependent binding affinities and reaction rates in pharmaceutical formulations.

Wavefunction delocalization and constructive quantum interference constitute the fundamental origin of covalent bonding, unifying molecular orbital and valence bond perspectives through a rigorous quantum mechanical framework. Experimental techniques from single-molecule conductance measurements to orbital imaging with functionalized STM tips provide direct validation of these quantum phenomena. Computational methodologies including energy decomposition analysis, the tribasis method, and advanced wavefunction theory enable precise quantification of delocalization effects across diverse chemical systems. For pharmaceutical researchers, these principles offer powerful design rules for optimizing molecular stability, binding affinity, and electronic properties through controlled quantum interference—establishing a direct pathway from fundamental quantum principles to applied molecular design.

For nearly six decades, the quantum mechanical explanation of the covalent chemical bond has been dominated by a paradigm established by Ruedenberg, primarily through his analysis of the hydrogen molecule (Hâ‚‚) and hydrogen molecular ion (Hâ‚‚âº). This model attributes bond formation primarily to a lowering of electron kinetic energy (KE) through wavefunction delocalization, followed by orbital contraction that restores virial balance. However, recent investigations utilizing modern computational and decomposition methods reveal this explanation does not universally extend to bonds involving heavier, multi-electron atoms. This technical analysis examines the evolving understanding of kinetic and potential energy balance during bond formation, synthesizing evidence that Pauli repulsion from core electrons in multi-electron systems fundamentally alters the bonding mechanism, necessitating a paradigm shift from a purely hydrogenic model to one emphasizing constructive quantum interference as the universal driving force.

The quantum mechanical description of the covalent bond represents one of the most significant applications of quantum theory to chemistry. The pioneering work of Ruedenberg in the 1960s provided a compelling and physically intuitive explanation for bond formation in H₂⺠and H₂, which has since been extensively generalized to other chemical bonds [15] [16].

The Virial Theorem and Its Traditional Interpretation

The virial theorem establishes a precise relationship between kinetic (T) and potential (V) energy changes in a bound quantum system at equilibrium. For a bond energy ΔE, the theorem dictates:

- Change in potential energy: ΔV = 2ΔE

- Change in kinetic energy: ΔT = -ΔE

This relationship appears to assign a dominant, stabilizing role to the decrease in potential energy, with the kinetic energy increasing and thus opposing bond formation [15]. However, this interpretation only applies to the system at equilibrium.

Ruedenberg's Kinetic Energy-Driven Bonding Model

Ruedenberg's analysis decomposed the bond formation process into distinct stages, revealing a more nuanced picture for hydrogenic systems [15] [16]:

- Initial Delocalization: As atoms approach, constructive quantum interference allows electron wavefunctions to delocalize across both nuclei.

- Kinetic Energy Lowering: This delocalization reduces the electron momentum uncertainty, significantly lowering the kinetic energy.

- Orbital Contraction: The KE lowering creates a virial imbalance, driving orbital contraction toward the nuclei.

- Potential Energy Lowering: Orbital contraction dramatically lowers potential energy, ultimately establishing the virial theorem ratio at equilibrium.

In Hâ‚‚ and Hâ‚‚âº, approximately two-thirds of the binding energy was attributed to this initial kinetic energy lowering [15]. This framework became the standard quantum mechanical explanation for covalent bonding across chemistry.

Challenging the Universality of KE-Lowering

Recent quantitative investigations using advanced energy decomposition analysis (EDA) methods reveal that Ruedenberg's model, while correct for hydrogen, fails to accurately describe bonding in systems with heavier, multi-electron atoms.

Evidence from Multi-Electron Systems

A landmark 2020 study by Levine and Head-Gordon employed a stepwise variational EDA based on absolutely localized molecular orbitals (ALMOs) to analyze KE and PE changes during bond formation for diverse molecules [15] [16]. Their findings demonstrate a fundamental dichotomy:

Table 1: Kinetic Energy Changes During Covalent Bond Formation

| Molecule/Bond | KE Change (ΔTCov) | Behavior Relative to H₂ |

|---|---|---|

| H₂⺠| Lowering | Reference |

| Hâ‚‚ | Lowering | Reference |

| H₃C–CH₃ (C–C) | Increasing | Opposite |

| F–F | Increasing | Opposite |

| H₃C–OH (C–O) | Increasing | Opposite |

| H₃C–SiH₃ (C–Si) | Increasing | Opposite |

| F–SiF₃ (F–Si) | Increasing | Opposite |

This data clearly indicates that the kinetic energy lowering observed in hydrogen is the exception rather than the rule. For bonds between heavier atoms, the initial interaction between radical fragments frequently results in a kinetic energy increase, despite the overall bond formation being substantially stabilizing [15].

The Core Electron Pauli Repulsion Effect

The critical factor differentiating hydrogen from heavier elements is the presence of core electrons [15]. Hydrogen atoms possess no core electrons—their bonding electrons occupy orbitals that can contract freely toward the nucleus during bond formation. In contrast, atoms such as carbon, oxygen, and fluorine contain core 1s electron pairs that are spatially compact and localized.

When atoms with core electrons approach:

- The bonding (valence) electrons experience significant Pauli repulsion from the core electrons of the other atom.

- This repulsion constricts the available space for valence electrons, increasing their momentum uncertainty via the Heisenberg principle.

- The consequent increase in kinetic energy can overwhelm any potential KE lowering from delocalization.

This explains the observational dichotomy: hydrogenic bonding follows the Ruedenberg (KE-lowering) mechanism, while bonding between heavier atoms follows a different mechanism where PE lowering and quantum resonance effects dominate [15].

Quantitative Methodologies: Decomposing the Bond Energy

To quantitatively test the Ruedenberg paradigm across different bonds, researchers require sophisticated energy decomposition analysis protocols. The ALMO-EDA method provides a rigorous, stepwise framework [15] [16].

ALMO-EDA Computational Protocol

Diagram 1: ALMO-EDA Energy Decomposition Workflow

The ALMO-EDA method decomposes the total interaction energy (ΔEINT = EFinal - EFrag) into physically meaningful components through a series of variationally optimized intermediate states [15] [16]:

Preparation (ΔEPrep): Energy change to distort isolated fragments from their optimal geometry and electronic structure to their configuration in the molecule.

- Computational Protocol: Fragment orbitals are geometrically fixed but electronic hybridization is adjusted.

Covalent Interaction (ΔECov): Energy change from constructive quantum interference between prepared fragment wavefunctions.

- Computational Protocol: For 2-electron bonds, a Heitler-London wavefunction is formed: ΨCov2e = c{Â[A↑][B↓] + Â[A↓][B↑]}.

- This step is identified as the stage where initial KE lowering occurred in Ruedenberg's analysis.

Orbital Contraction (ΔECon): Energy stabilization from orbital contraction toward nuclei.

- Computational Protocol: Empty "contraction response orbitals" are generated per occupied orbital via coupled-perturbed SCF calculation responding to perturbed nuclear charges.

Polarization & Charge Transfer (ΔEPCT): Remaining stabilization from bond polarization and inter-fragment charge transfer.

- Computational Protocol: Final relaxation to unconstrained CAS(2,2) wavefunction.

The kinetic energy component for each step (ΔTPrep, ΔTCov, ΔTCon) can be computed analogously to the total energy components, enabling precise tracking of KE evolution during bonding [16].

Research Reagent Solutions: Computational Tools

Table 2: Essential Computational Resources for Bond Energy Analysis

| Resource/Tool | Function in Analysis | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| ALMO-EDA Code | Energy decomposition into physical components | Partitioning ΔEINT into preparation, covalent, contraction, and charge-transfer terms |

| Gaussian 16 Suite | Electronic structure calculations | Performing SCF, CAS(2,2), and intrinsic reaction coordinate (IRC) computations |

| NBO 3.1 Program | Natural Bond Orbital analysis | Calculating Mayer bond orders along reaction coordinates |

| Kudi Program | Reaction coordinate analysis | Determining reaction electronic flux (REF), KE, PE along pathways |

| Custom Python Scripts | Data processing & customization | Extending analysis beyond standard software capabilities |

Beyond Simple Diatomics: Multi-Bond Reactions

The re-evaluation of energy balances extends to more complex chemical transformations involving simultaneous formation/breaking of multiple bonds. A 2024 study applied the reaction electronic flux (REF) methodology to analyze KE and PE variations in concerted σ-bond metathesis reactions activating CO₂ with low-valent group 14 catalysts [17].

Kinetic and Potential Energy Precedence

Analysis across the reaction coordinate revealed that changes in KE and PE precede the maximum electronic activity (REF) associated with bond formation and dissociation processes [17]. This temporal sequencing suggests:

- KE and PE changes create the electronic environment necessary for major bond reorganization.

- The REF serves as an indicator of electronic activity driven by these energy redistributions.

- In these multi-bond processes, the energy redistribution mechanism may differ from both traditional hydrogenic and single-bond multi-electron cases.

Implications for Reaction Mechanism Analysis

These findings highlight the necessity of going beyond simple bond analysis to understand complex reactions where:

- Multiple bonds form and break concertedly.

- Heavier elements with significant core electron densities participate.

- Catalytic processes involve significant electronic reorganization.

The REF methodology, combined with KE/PE analysis along reaction coordinates, provides a more nuanced picture of electronic driving forces in complex bond rearrangements [17].

Discussion: A New Unified View of Chemical Bonding

The accumulated evidence demands a revised, unified understanding of covalent bond formation that acknowledges the different energy balances in hydrogenic versus multi-electron systems.

The Central Role of Constructive Quantum Interference

While the specific kinetic and potential energy balances differ between bonding types, constructive quantum interference (or resonance) emerges as the universal origin of chemical bonding [15] [16]. The key distinctions arise from differences in the interfering states:

- In hydrogenic systems, interference occurs between atomic orbitals that can contract freely, leading to KE lowering.

- In multi-electron systems, interference occurs between orbitals constrained by Pauli repulsion from core electrons, often leading to KE increase.

Updated Bond Formation Taxonomy

The modern understanding suggests a classification of bond formation mechanisms based on energy profiles:

Table 3: Classification of Bond Formation Mechanisms by Energy Profiles

| Bond Type | KE During Initial Interaction | Dominant Stabilizing Factor | Orbital Contraction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen (H–H) | Lowering | Kinetic Energy Reduction | Significant |

| Light Element (C–C, C–O) | Increasing or Neutral | Potential Energy Lowering & Resonance | Minimal |

| Charge-Shift Bonds | Variable resonance | Resonance Stabilization | Dependent on polarity |

| Polar Covalent | Increasing | Mixed Electrostatic & Covalent | Moderate |

Implications for Drug Development and Materials Science

This refined understanding of chemical bonding has practical implications for molecular design in pharmaceutical and materials applications:

- Predicting Bond Strengths: Accurate prediction of bond dissociation energies requires methods sensitive to the different energy balances in various bond types.

- Reactivity Assessment: Chemical reactivity often correlates with bond weakening or strengthening trends that follow from the underlying energy distribution.

- Catalyst Design: Understanding how KE and PE evolve during bond formation informs the design of catalysts that stabilize transition states through specific energy component manipulation.

- Molecular Dynamics: Force fields and simulation parameters should account for the element-specific bonding energetics revealed by these studies.

The long-standing paradigm of kinetic-energy-driven covalent bonding, while valid for the simple hydrogen systems from which it was derived, requires significant refinement for application to multi-electron systems. Evidence from advanced computational analyses demonstrates that:

- Pauli repulsion from core electrons in heavier elements fundamentally alters the energy balance during bond formation.

- Kinetic energy increases, rather than decreases, during initial bond formation for many common bonds between heavier atoms.

- Constructive quantum interference represents the universal driving force for covalent bonding, with variations in KE/PE balance representing secondary effects dependent on atomic composition.

This re-evaluation does not diminish Ruedenberg's foundational contribution but rather refines it for broader application across the periodic table. Future research directions should focus on extending this analysis to more complex bonding situations, including transition metal complexes, frustrated Lewis pairs, and catalytic transition states, where the precise balance of kinetic and potential energy components may dictate reactivity and selectivity in chemically and pharmaceutically relevant systems.

The Pauli Exclusion Principle, formulated by Wolfgang Pauli in 1925, is a fundamental tenet of quantum mechanics that states no two identical fermions (particles with half-integer spin, such as electrons) can occupy the same quantum state simultaneously within a quantum system [18] [19]. For electrons in an atom, this means that no two electrons can have an identical set of the four quantum numbers: the principal quantum number (n), the azimuthal quantum number (l), the magnetic quantum number (mâ„“), and the spin quantum number (ms) [18]. In practical chemical terms, this principle directly implies that no more than two electrons can occupy the same atomic orbital, and these two electrons must have opposite spins (antiparallel) [20] [21].

This principle provides the fundamental quantum mechanical explanation for two interconnected phenomena: the saturation of chemical bonds—why covalent bonds form between a specific, limited number of atoms—and the chemical inertness of rare gases—why noble gas elements like helium and neon exhibit minimal chemical reactivity [19] [22]. Within the broader context of research on the quantum mechanical description of chemical bond formation, the Pauli Exclusion Principle establishes the foundational constraints that govern electron distribution in atoms and molecules, without which the structural diversity and stability of matter would be impossible [9] [15].

Theoretical Foundation of the Pauli Exclusion Principle

Quantum Numbers and Electron Identity

The unique identity of every electron in an atom is described by a set of four quantum numbers:

- Principal quantum number (n): Defines the main energy level or shell (n = 1, 2, 3,...) [21].

- Azimuthal quantum number (l): Defines the subshell or shape of the orbital within a shell (l = 0 to n-1) [21].

- Magnetic quantum number (mâ„“): Specifies the orientation of the orbital in space (mâ„“ = -l to +l) [21].

- Spin quantum number (ms): Describes the intrinsic angular momentum of the electron, with only two possible values: +1/2 (spin-up) or -1/2 (spin-down) [18] [21].

The Pauli Exclusion Principle mandates that for any two electrons in the same atom, at least one of these four quantum numbers must differ [18]. Since an atomic orbital is defined by a specific set of n, l, and mâ„“ quantum numbers, this restriction means each orbital can accommodate a maximum of two electrons, and they must have opposite spins (different ms values) [20].

Fermions, Bosons, and Wave Function Symmetry

The principle applies universally to all fermions (particles with half-integer spin such as 1/2, 3/2), including electrons, protons, and neutrons [18] [19]. In contrast, bosons (particles with integer spin such as 0, 1) are not subject to the exclusion principle and can occupy the same quantum state [18] [19].

This distinction arises from the fundamental symmetry properties of the quantum mechanical wave function that describes a system of identical particles:

- For fermions, the total wave function must be antisymmetric (changes sign) with respect to the exchange of any two identical particles [18] [19].

- For bosons, the total wave function must be symmetric (remains unchanged) under particle exchange [18] [19].

If two fermions, such as electrons, were to occupy the same quantum state, exchanging them would leave the wave function unchanged, violating the requirement for antisymmetry. The only mathematical solution is that the probability of finding two fermions in the same state is zero, which is the formal statement of the exclusion principle [18].

Table 1: Particle Classification Based on Spin and Statistical Behavior

| Particle Type | Spin | Statistical Behavior | Governed by Pauli Exclusion? | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fermions | Half-integer | Fermi-Dirac statistics | Yes | Electrons, protons, neutrons, quarks |

| Bosons | Integer | Bose-Einstein statistics | No | Photons, mesons, helium-4 atoms |

Pauli Exclusion and Electron Configuration in Atoms

The Aufbau Principle and Shell Structure

The Pauli Exclusion Principle provides the underlying physical basis for the Aufbau principle (building-up principle), which governs how electrons successively fill atomic orbitals [22]. Without the exclusion principle, all electrons in an atom would collapse into the lowest energy orbital (1s), fundamentally altering atomic structure and chemical behavior [19] [22].

The sequential filling of electron shells according to the exclusion principle directly explains the empirical pattern of the periodic table. The closing of electron shells at specific numbers (2, 8, 18, 32...) corresponds to the noble gas configurations and the periodicity of chemical properties [19] [22]. These "magic numbers" emerge from the cumulative capacity of successive energy shells when the maximum of two electrons per orbital is enforced [22].

Table 2: Electron Capacity of Atomic Shells and Subshells

| Shell (n) | Subshell Types | Orbitals per Subshell | Electrons per Subshell | Total Electrons in Shell |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (K) | s | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| 2 (L) | s, p | 1, 3 | 2, 6 | 8 |

| 3 (M) | s, p, d | 1, 3, 5 | 2, 6, 10 | 18 |

| 4 (N) | s, p, d, f | 1, 3, 5, 7 | 2, 6, 10, 14 | 32 |

Quantum Mechanical Explanation of Rare Gas Inertness

The exceptional chemical inertness of noble gases (He, Ne, Ar, Kr, Xe, Rn) finds its fundamental explanation in the Pauli Exclusion Principle combined with energy considerations [19] [22]. These elements possess completely filled electron shells with particularly stable configurations [22].

For example:

- Helium (He): The 1s orbital is completely filled with two electrons of opposite spin (1s²) [19] [21].

- Neon (Ne): Has the completely filled electron configuration 1s²2s²2pâ¶, with all orbitals containing their maximum complement of two electrons with paired spins [22].

The stability of these configurations arises because:

- All electrons in the closed shells are paired with opposite spins, satisfying the exclusion principle in the most stable arrangement [20].

- The next available atomic orbital would belong to a higher energy shell, requiring significant energy input to accommodate an additional electron [19].

- Removing an electron would break a stable, filled-shell configuration, also requiring substantial energy [19].

This combination of filled shells and substantial energy barriers to electron addition or removal makes noble gases predominantly unreactive, as any chemical reaction would involve altering this stable electron configuration [22].

Figure 1: Causal chain from the Pauli Exclusion Principle to noble gas inertness, showing how the principle dictates electron configuration and ultimately chemical behavior.

Bond Saturation in Covalent Bond Formation

The Quantum Mechanical Basis of Covalent Bonding

In covalent bond formation, the Pauli Exclusion Principle plays a decisive role in limiting the number of bonds an atom can form and explaining why certain bonding configurations are stable while others are forbidden. When two atoms approach each other to form a bond, their atomic orbitals overlap to form molecular orbitals [9].

According to valence bond theory, a covalent bond forms when:

- Two atomic orbitals, one from each atom, merge with one another (overlap) [9].

- The electrons they contain pair up (so their spins are ↓↑) [9].

The bonding interaction is stabilized by the increased electron density between the two nuclei, which is achieved through constructive interference between the electron wavefunctions [9] [15]. However, this favorable interaction is strictly constrained by the Pauli Exclusion Principle, which prevents multiple electrons from occupying the same quantum state in the resulting molecular system [9].

The Saturation Phenomenon Explained

The saturation of covalent bonds—the observation that atoms form a limited number of bonds—directly follows from the Pauli Exclusion Principle. Consider the bonding in common molecules:

Hydrogen (Hâ‚‚): Each hydrogen atom contributes one electron to the bond. These two electrons pair with opposite spins in the bonding molecular orbital, forming a single covalent bond. A third electron cannot join this bond because it would necessarily have the same spin as one of the existing electrons, violating the exclusion principle [9].

Water (H₂O): Oxygen has six valence electrons (2s²2pⴠconfiguration). It can form two covalent bonds with hydrogen atoms, with the four non-bonding electrons occupying two lone pairs. Each bond consists of two electrons with paired spins, and no additional bonds can form without violating the exclusion principle by forcing electrons into already-filled orbitals [19].

The limitation arises because:

- Each bonding orbital has a maximum capacity of two electrons with paired spins [20].

- Once a bonding orbital is filled, additional electrons must occupy higher-energy antibonding orbitals, which would destabilize the bond [9].

- The number of unpaired electrons in the valence shell determines the maximum number of covalent bonds an atom can form through electron pairing [9].

Figure 2: Quantum mechanical process of covalent bond formation and saturation, showing how orbital overlap and electron pairing lead to bond saturation through the Pauli Exclusion Principle.

Pauli Repulsion in Chemical Bonding

Beyond explaining bond saturation, the Pauli Exclusion Principle manifests in chemical interactions through Pauli repulsion (also called exchange repulsion or steric repulsion) [23]. When two atoms or molecules approach each other closely, their electron clouds begin to overlap significantly. The Pauli Principle forces some of these electrons into higher-energy states to avoid occupying identical quantum states, resulting in a repulsive energy contribution [23].

This repulsive interaction:

- Prevents complete collapse of molecules by balancing attractive forces [23].

- Determines the equilibrium distances and geometries in molecules [23].

- Explains the directional nature of certain chemical bonds, such as in halogen bonding [23].

Despite its quantum mechanical origin, Pauli repulsion can be accurately modeled classically as arising from diminished screening of nuclear charges when electron densities overlap, leading to increased nuclear-nuclear repulsion according to Coulomb's law [23].

Quantitative Analysis and Experimental Validation

Energy Decomposition Analysis in Bond Formation

Advanced computational methods like Energy Decomposition Analysis (EDA) based on Absolutely Localized Molecular Orbitals (ALMOs) allow researchers to quantitatively separate the different energy contributions during bond formation, including those directly related to the Pauli Exclusion Principle [15].

Recent studies using ALMO-EDA reveal that the traditional view of covalent bond formation being primarily driven by kinetic energy lowering (as established for H₂⺠and H₂) does not universally apply to bonds between heavier elements [15]. For molecules such as H₃C–CH₃, F–F, and H₃C–OH, the kinetic energy often increases during initial bond formation, with the stabilizing interaction instead coming primarily from potential energy lowering [15]. This difference arises from Pauli repulsion between bonding electrons and core electrons in heavier atoms [15].

Table 3: Kinetic and Potential Energy Changes During Covalent Bond Formation for Selected Molecules

| Molecule | Bond Type | Kinetic Energy Change (ΔT) | Potential Energy Change (ΔV) | Primary Stabilizing Factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H₂⺠| 1-electron | Significant decrease | Moderate decrease | Kinetic energy lowering |

| Hâ‚‚ | Covalent | Significant decrease | Moderate decrease | Kinetic energy lowering |

| H₃C–CH₃ | C–C single | Increase | Significant decrease | Potential energy lowering |

| F–F | Covalent | Increase | Significant decrease | Potential energy lowering |

| H₃C–OH | C–O single | Slight increase | Significant decrease | Potential energy lowering |

Spectroscopic Evidence and Historical Development

The experimental foundation for the Pauli Exclusion Principle emerged from atomic spectroscopy in the early 20th century [22]. Key evidence included:

- The anomalous Zeeman effect (magnetic splitting of spectral lines), which revealed the need for a fourth quantum number to fully describe electron states [22].

- The regularities in the periodic table, particularly the "magic numbers" 2, 8, 18, 32... corresponding to noble gas configurations [22].

- The work of Edmund C. Stoner (1924), who recognized that the number of energy levels for a single electron in alkali metals matches the number of electrons in closed shells of noble gases [18] [22].

Pauli resolved these puzzles by introducing the exclusion principle in 1925, initially for electrons, later extending it to all fermions through the spin-statistics theorem in 1940 [18] [22].

Research Methodologies and Computational Approaches

Experimental Protocols for Studying Pauli Exclusion Effects

Protocol 1: Symmetry-Adapted Perturbation Theory (SAPT) for Exchange Repulsion Measurement

Purpose: To quantitatively separate exchange repulsion (Pauli repulsion) energy from other components of intermolecular interactions [23].

Methodology:

- Select a database of molecular dimers (e.g., S101 database) representing diverse interaction types [23].

- Perform high-level quantum chemical calculations to determine reference interaction energies.

- Apply SAPT to decompose the total interaction energy into components:

- Electrostatic energy

- Exchange repulsion (Pauli repulsion)

- Induction energy

- Dispersion energy [23]

- Fit classical repulsion models to the ab initio exchange repulsion energies.

- Validate the model against experimental data such as crystal structures and thermodynamic measurements [23].

Key Parameters:

- Exchange repulsion energy as a function of intermolecular distance and orientation [23].

- Anisotropy of repulsion based on atomic multipole moments [23].

- Transferability of parameters across different chemical environments [23].

Protocol 2: Absolutely Localized Molecular Orbital Energy Decomposition Analysis (ALMO-EDA)

Purpose: To analyze energy changes during stepwise bond formation, isolating kinetic and potential energy contributions [15].

Methodology:

- Prepare isolated fragments in their ground state geometries and electronic structures (EFrag) [15].

- Distort fragments to their molecular geometry and hybridization (EPrep) [15].

- Allow constructive quantum interference between prepared fragment wavefunctions with fixed orbitals (ECov) [15].

- Permit orbital contraction by including contraction response orbitals (ECon) [15].

- Allow final polarization and charge transfer to reach the full CAS(2,2) wavefunction (EFinal) [15].

- Calculate kinetic and potential energy changes at each step, particularly during the covalent interaction step (ΔECov) [15].

Key Outputs:

- Kinetic energy change during initial bond formation [15].

- Role of orbital contraction in different bond types [15].

- Distinction between bonds with light (H-containing) and heavy atoms [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Methods

Table 4: Essential Computational Methods and Their Applications in Studying Pauli Exclusion Effects

| Method/Software | Primary Function | Application to Pauli Exclusion Research | Key Output Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Symmetry-Adapted Perturbation Theory (SAPT) | Decompose intermolecular interaction energies | Quantify exchange repulsion (Pauli repulsion) energy component | Exchange repulsion energy, anisotropy parameters |

| Absolutely Localized Molecular Orbital EDA (ALMO-EDA) | Stepwise analysis of bond formation energy | Isolate kinetic and potential energy changes during bond formation | ΔECov, ΔECon, kinetic energy changes |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) with dispersion correction | Electronic structure calculation | Model Pauli repulsion in complex molecular systems | Interaction energies, electron density maps |

| Complete Active Space SCF (CASSCF) | Multi-configurational wavefunction calculation | Describe electron correlation in systems with strong Pauli repulsion | Configuration weights, natural orbitals |

| Atomic Multipole Optimized Energetics (AMOEBA) | Polarizable force field with atomic multipoles | Model anisotropic Pauli repulsion in biomolecular simulations | Repulsion energy, molecular geometries |

| 5-Phenylpenta-2,4-dienal | 5-Phenylpenta-2,4-dienal, CAS:13466-40-5, MF:C11H10O, MW:158.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Europium bromide (EuBr3) | Europium bromide (EuBr3), CAS:13759-88-1, MF:Br3Eu, MW:391.68 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Implications for Drug Development and Materials Science

The Pauli Exclusion Principle has profound implications for drug development and materials design, influencing properties ranging from molecular recognition to bulk material behavior.

In drug discovery, Pauli repulsion determines:

- Binding specificity: The precise steric complementarity between drugs and their targets depends on Pauli repulsion to prevent overly tight binding that would inhibit function [23].

- Halogen bonding: The anisotropic nature of Pauli repulsion around halogen atoms creates directional "sigma-hole" interactions that can be exploited for selective binding [23].

- Conformational preferences: The principle governs the allowed conformations of flexible drugs through steric constraints [23].

In materials science, the exclusion principle explains:

- Electrical conduction in metals: Conduction electrons remain delocalized because the low-energy states in atoms are already occupied, enforcing electron mobility [19].

- Mechanical properties of solids: The resistance of matter to compression arises fundamentally from Pauli repulsion between electron clouds [19].

- Superconductivity: Cooper pairs of electrons effectively behave as bosons, bypassing the exclusion principle to enable superconductivity [19].

The Pauli Exclusion Principle provides the fundamental quantum mechanical explanation for both bond saturation and the inertness of rare gases. By prohibiting multiple electrons from occupying the same quantum state, the principle dictates electron configuration in atoms, limits the number of covalent bonds atoms can form, and explains the exceptional stability of closed-shell noble gas configurations.

Recent research has revealed surprising complexities in how the principle manifests chemically. While traditional models emphasized kinetic energy lowering in bond formation, studies of heavier atoms show potential energy lowering often dominates, with Pauli repulsion between core and bonding electrons playing a decisive role [15]. The development of anisotropic repulsion models based on atomic multipoles represents a significant advance in achieving "chemical accuracy" (within 1 kcal/mol) in molecular simulations [23].

Future research directions include:

- Refining anisotropic Pauli repulsion models for biomolecular force fields [23].

- Exploring the role of Pauli exclusion in emerging materials like quantum dots and 2D materials [20].

- Developing more efficient computational methods to handle the exchange interaction in large systems [15].

- Experimental probes of Pauli exclusion effects at the single-molecule level using advanced spectroscopic techniques.

The Pauli Exclusion Principle remains not merely a historical foundation of quantum theory but an active research frontier with continuing implications for understanding and designing molecular interactions in chemistry, biology, and materials science.

In the realm of quantum chemistry, two principal theoretical frameworks have emerged to explain the formation and nature of chemical bonds: Valence Bond (VB) Theory and Molecular Orbital (MO) Theory. Both approaches represent sophisticated developments beyond classical Lewis structures and VSEPR theory, providing a quantum mechanical foundation for understanding how atoms combine to form molecules [24] [25]. These theories form the cornerstone of modern chemical bonding research, offering complementary insights that are indispensable for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to understand molecular behavior at the most fundamental level.

Valence Bond Theory, pioneered by Heitler and London in 1927, maintains the identity of individual atoms while explaining bonding through the quantum mechanical overlap of their atomic orbitals [25]. In contrast, Molecular Orbital Theory, developed by Hund and Mulliken in 1932, describes molecules as unified quantum systems with orbitals that span the entire molecular framework [25]. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of both conceptual frameworks, their mathematical foundations, experimental validations, and practical applications in advanced chemical research, particularly relevant to pharmaceutical development and materials science.

Theoretical Foundations and Mathematical Frameworks

Valence Bond Theory: Core Principles and Postulates

Valence Bond Theory conceptualizes chemical bonding as occurring through the overlap of half-filled atomic orbitals from adjacent atoms [26] [27]. The theory rests on three fundamental postulates: (1) covalent bonds form when half-filled atomic orbitals of two atoms overlap, (2) the overlapping orbitals must contain electrons with opposite spins to enable pairing and bond formation, and (3) bond strength correlates directly with the extent of orbital overlap, with greater overlap producing stronger bonds and higher electron density between nuclei [26].

The mathematical representation of VB theory employs wave functions that describe the linear combination of atomic orbitals. The wave function (Ψ) for the molecule is expressed as:

Ψ = Σcᵢφᵢ

where cᵢ represents coefficients and φᵢ represents the atomic orbitals [28]. This approach preserves atomic identity while accounting for bond formation through orbital overlap, creating a localized bond picture that aligns well with classical structural formulas [25].

Molecular Orbital Theory: Fundamental Concepts

Molecular Orbital Theory represents a more delocalized approach where atomic orbitals combine to form molecular orbitals that extend across the entire molecule [24] [25]. The foundational principle of MOT is the Linear Combination of Atomic Orbitals (LCAO) method, where molecular orbitals are constructed from mathematical combinations of atomic wave functions [24].