Quantum Subspace Expansion: Revolutionizing Molecular Energy Calculations for Drug Discovery

This article explores Quantum Subspace Expansion (QSE) as a transformative computational technique for calculating molecular energies, a critical task in drug discovery and development.

Quantum Subspace Expansion: Revolutionizing Molecular Energy Calculations for Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article explores Quantum Subspace Expansion (QSE) as a transformative computational technique for calculating molecular energies, a critical task in drug discovery and development. We provide a comprehensive analysis for researchers and pharmaceutical professionals, covering the foundational principles of QSE, its methodological implementation in simulating molecular systems, strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing performance on noisy hardware, and a comparative validation against other quantum algorithms. The discussion synthesizes recent breakthroughs and practical insights, highlighting QSE's potential to drastically reduce the time and cost associated with bringing new therapeutics to market.

What is Quantum Subspace Expansion? The Foundation for Advanced Molecular Simulation

Defining Quantum Subspace Expansion (QSE) and its Core Principles

Quantum Subspace Expansion (QSE) is a post-processing algorithm for quantum computers that enhances the accuracy of ground and excited state energy calculations. It operates by constructing and diagonalizing an effective Hamiltonian within a small, classically-tractable subspace built upon a initial quantum state, known as a "root state" [1] [2]. This method has emerged as a powerful alternative to purely variational approaches, such as the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE), offering a pathway to mitigate errors and perform spectral calculations on noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices without significantly increasing quantum circuit depth [1] [3] [2].

The core value of QSE lies in its hybrid quantum-classical nature. A quantum processor is used to prepare a starting state and measure the matrix elements needed to define the subspace, while a classical computer solves a generalized eigenvalue problem to find the best energy eigenvalues and eigenvectors within that subspace [4]. This makes QSE particularly promising for near-term quantum hardware, as it exchanges increased circuit depth for additional measurements, a resource that is often more readily available than perfect, long-coherence quantum gates [3].

Theoretical Foundation and Mathematical Framework

Core Mathematical Principle

The foundational principle of QSE is to expand a prepared quantum root state, ( \rho0 ), into a subspace spanned by applying a set of ( L ) Hermitian expansion operators ( {\sigmai} ). The states within this subspace are expressed as: [ \rho{\text{SE}}(\vec{c}) = \frac{W^\dagger \rho0 W}{\Tr[W^\dagger \rho0 W]}, \quad \text{with} \quad W = \sum{i=1}^{L} ci \sigmai ] where ( \vec{c} = (c1, \dots, cL) ) is a vector of complex coefficients that parametrize the subspace [1]. The expectation value of an observable ( O ) within this subspace is given by the Rayleigh-Ritz quotient: [ \Tr[O\rho{\text{SE}}(\vec{c})] = \frac{\sum{i,j=1}^{L} ci^* cj \mathcal{O}{ij}}{\sum{i,j=1}^{L} ci^* cj \mathcal{S}{ij}} ] where ( \mathcal{O}{ij} = \Tr[\sigmai^\dagger \rho0 \sigmaj O] ) and ( \mathcal{S}{ij} = \Tr[\sigmai^\dagger \rho0 \sigmaj] ) [1]. The matrices ( \mathcal{H}{ij} = \Tr[\sigmai^\dagger \rho0 \sigmaj H] ) (subspace-projected Hamiltonian) and ( \mathcal{S}{ij} ) (overlap matrix) are measured on the quantum computer.

The Generalized Eigenvalue Problem

To find the ground or excited states, QSE solves the generalized eigenvalue problem: [ \mathcal{H} \vec{c} = \lambda \mathcal{S} \vec{c} ] Here, ( \mathcal{H} ) is the matrix representation of the Hamiltonian in the subspace, ( \mathcal{S} ) is the overlap matrix, and the eigenvalues ( \lambda ) correspond to the energy estimates for the states within the subspace [4]. The lowest eigenvalue ( \lambda_0 ) provides an improved estimate of the ground state energy. Solving this equation is a classical computation step, making it tractable for reasonable subspace dimensions ( L ).

The Krylov Subspace

A particularly effective choice for the expansion operators is using powers of the Hamiltonian, ( H^p ). This generates a Krylov subspace [1]. The overlap of the states ( H^p \rho0 H^{p\dagger} ) with the true ground state increases exponentially with ( p ), provided the root state ( \rho0 ) has non-zero overlap with the true ground state [1]. This connects QSE to well-established classical Krylov subspace diagonalization methods, known for their rapid convergence for ground state problems [1] [3].

Key Protocols and Experimental Methodologies

Protocol 1: Standard QSE for Molecular Excited States

This protocol outlines the standard procedure for performing a QSE calculation to compute ground and excited states of a molecular system on a quantum computer, following the example of a minimal basis hydrogen molecule [4].

Step 1: Define the Problem and Generate the Initial State

- Construct the molecular Hamiltonian ( H ) in the fermionic space and map it to a qubit operator using a mapping such as Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev [4].

- Prepare a root state ( \rho_0 ) close to the ground state. This is often the optimized state from a VQE calculation using an ansatz like UCCSD [4].

Step 2: Define the Expansion Subspace

- Select a set of expansion operators ( {\sigmai} ). For molecular excited states, these are often chosen as fermionic excitation operators. For example, to generate spin-adapted states, one can use singlet single excitation operators ( E{ij} ) [4].

- Map these operators to the qubit space.

Step 3: Quantum Measurement of Matrix Elements

- On the quantum computer, measure all matrix elements of the projected Hamiltonian ( \mathcal{H}{ij} = \langle \psi{ij} | H | \psi{kl} \rangle ) and the overlap matrix ( \mathcal{S}{ij} = \langle \psi{ij} | \psi{kl} \rangle ), where ( |\psi_{ij}\rangle ) are the states generated by applying the expansion operators to the root state [4].

- This can be done using shot-based protocols like Pauli Averaging [4].

Step 4: Classical Post-Processing

- On a classical computer, solve the generalized eigenvalue problem ( \mathcal{H}\vec{c} = \lambda \mathcal{S}\vec{c} ) [4].

- Handle numerical instabilities, often caused by near-linear dependencies in the basis (ill-conditioning of ( \mathcal{S} )), by removing dimensions corresponding to small singular values of ( \mathcal{S} ) via truncation [4].

Step 5: Analysis

- The eigenvalues ( \lambda ) correspond to the energies of the ground and excited states within the subspace.

- The eigenvectors ( \vec{c} ) define the expanded state within the subspace.

Protocol 2: Large-Scale QSE with Classical Shadows

A major bottleneck in QSE is the measurement overhead required to estimate all matrix elements ( \mathcal{H}{ij} ) and ( \mathcal{S}{ij} ). This protocol leverages informationally complete (IC) measurements, specifically classical shadows, to overcome this bottleneck and enable large-scale implementations [1].

Step 1: Prepare the Root State

- Prepare the root state ( \rho_0 ) on the quantum processor.

Step 2: Perform Informationally Complete Measurements

- Instead of measuring each observable individually, perform randomized measurements on the state ( \rho_0 ). A classical shadow is a classical snapshot of the quantum state, built from these randomized measurements [1].

- For each of many measurement basis randomizations (e.g., over 32,000 per circuit), collect measurement samples [1] [5].

Step 3: Construct Classical Shadows and Estimate Matrices

- From the collected samples, reconstruct unbiased estimators for the matrix entries of ( \mathcal{H} ) and ( \mathcal{S} ) by processing the classical shadows [1].

- This allows for the simultaneous estimation of a vast number of Pauli observables from the same set of measurements. One implementation evaluated over ( 10^{14} ) Pauli traces for an 80-qubit system [1] [5].

Step 4: Reformulate as a Constrained Optimization

- To avoid numerical ill-conditioning from direct matrix inversion and to obtain rigorous statistical error bars, reformulate the QSE problem as a constrained optimization problem [1].

- This involves finding the minimal expectation value ( \min{\vec{c}} \Tr[H\rho{\text{GSE}}(\vec{c})] ) given a maximally tolerated statistical error, which provides an external tuning knob to control the trade-off between potential bias and variance [1].

Key Application: This protocol has been successfully demonstrated for probing quantum phase transitions in spin models with three-body interactions, achieving accurate ground state energy recovery for systems of up to 80 qubits [1] [5].

Protocol 3: Partitioned QSE (PQSE) for Numerical Stability

The Partitioned Quantum Subspace Expansion (PQSE) is an iterative generalization of QSE designed to improve numerical stability in the presence of finite sampling noise [3].

Step 1: Build a Krylov Subspace

- Follow the standard Krylov-based QSE approach to build an initial subspace using powers of the Hamiltonian.

Step 2: Iterative Partitioning and Recombination

- Instead of diagonalizing the entire Krylov subspace at once, the algorithm breaks it down into a sequence of smaller subspaces [3].

- These subspaces are connected sequentially via their lowest-energy states. The solution from one subspace informs the construction of the next.

Step 3: Variance-Based Sequencing

- A variance-based criterion is used to determine a "good" iterative sequence. This criterion helps ensure stability against statistical noise [3].

Step 4: Classical Diagonalization

- Diagonalize the Hamiltonian in each of the smaller, connected subspaces. This requires additional classical processing with polynomial overhead but uses the same quantum resources as the single-step approach [3].

Key Advantage: PQSE substantially alleviates the numerical instability that limits the accuracy of standard QSE in a parameter-free way, without requiring additional quantum measurements [3].

The workflow below illustrates the logical relationship and decision points between these three primary QSE protocols.

Critical Reagents and Computational Tools

Successful implementation of QSE relies on a suite of theoretical constructs and software tools. The table below details the key "research reagents" essential for experiments in this field.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Quantum Subspace Expansion

| Category | Reagent / Tool | Function in QSE Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Constructs | Krylov Subspace [1] [3] | A subspace spanned by powers of the Hamiltonian ( (H^p) ) applied to a root state. Provides rapid convergence for ground state calculations. |

| Expansion Operators [4] | A set of operators ( {\sigma_i} ) (e.g., fermionic excitations, Pauli strings) used to define the search subspace beyond the root state. | |

| Classical Shadows [1] [5] | A framework for informationally complete (IC) measurements that dramatically reduces the measurement overhead for estimating many observables. | |

| Software & Libraries | InQuanto [4] | A quantum computational chemistry toolkit that provides high-level interfaces (e.g., AlgorithmQSE) to run QSE calculations. |

| Qiskit / SQD Addon [6] | An open-source SDK for quantum computing. The SQD (Sample-Based Quantum Diagonalization) addon implements related subspace methods. | |

| Tangelo [7] | An open-source quantum chemistry package, used in hybrid workflows like DMET-SQD for fragment-based simulations. | |

| Hardware & Backends | Pauli Averaging [4] | A shot-based protocol for estimating expectation values of Pauli operators on quantum hardware or simulators. |

| Quantum Processing Units (QPUs) | Physical quantum devices (e.g., IBM's Eagle processor [7] [6]) used to execute quantum circuits and sample measurement outcomes. |

Quantitative Performance and Applications

QSE and related subspace methods have been demonstrated on a variety of problems, from small molecules to large spin models. The following table summarizes key quantitative results from recent experimental implementations.

Table 2: Performance Metrics of QSE and Related Subspace Methods in Recent Implementations

| System / Application | Method | System Size (Qubits) | Key Performance Metric | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Molecule (Hâ‚‚) | Standard QSE | N/A | Successfully obtained ground and spin-adapted excited states beyond VQE solution. | [4] |

| Spin Model with Three-Body Interactions | QSE + Classical Shadows | 16 to 80 | Accurate ground state recovery and mitigation of local order parameters; over 32,768 measurement basis randomizations per circuit. | [1] [5] |

| Cyclohexane Conformers | DMET-SQD (Related method) | 27 to 32 | Energy differences between conformers within 1 kcal/mol of classical benchmarks (chemical accuracy). | [7] |

| Water & Methane Dimers (Non-covalent interactions) | SQD (Related method) | 27 to 54 | Binding energy deviations within 1.000 kcal/mol from leading classical methods (CCSD(T)). | [6] |

| General Quantum Subspace Methods | PQSE | N/A | Displays improved numerical stability over single-step QSE in the presence of finite sampling noise. | [3] |

Quantum Subspace Expansion has established itself as a versatile and powerful algorithm within the quantum computing toolkit for molecular energy calculations. Its core principle—using a quantum computer to inform a small, classically-solvable subspace model—enables a flexible trade-off between quantum and classical resources. The development of advanced protocols incorporating classical shadows for scalability and partitioned approaches for numerical stability is pushing the boundaries of what is possible on today's noisy quantum devices.

As quantum hardware continues to improve, QSE and its generalizations are poised to play a critical role in achieving practical quantum advantage in computational chemistry and materials science, with significant potential implications for drug discovery and the design of novel materials.

The Critical Challenge of Molecular Energy Calculations in Drug Discovery

The process of drug discovery is characterized by significant financial investment, often ranging between $1-3 billion, with a typical timeline of 10 years and a success rate of only 10% [8]. This inefficiency highlights a critical need for innovative approaches to enhance the drug development pipeline. At the heart of this challenge lies the accurate calculation of molecular energies—the precise computational prediction of how potential drug molecules interact with biological targets, their stability, and their reactivity under physiological conditions.

Traditional computing methods struggle to accurately simulate quantum effects in complex molecular systems, particularly for large molecules and complex reactions like covalent bond formation [8]. Quantum subspace expansion (QSE) represents a transformative approach to this problem, offering a framework for performing electronic structure calculations on quantum computers with theoretical guarantees absent in parameter-optimization-based algorithms [9]. These methods are specially designed to be compatible with near-term quantum hardware constraints while providing pathways to exponential improvements in computational efficiency for specific chemical simulations [9].

This application note details practical protocols for implementing quantum subspace expansion methods to address critical challenges in drug discovery, focusing on real-world applications including prodrug activation and covalent inhibitor design.

Theoretical Framework: Quantum Subspace Expansion Fundamentals

Quantum subspace methods comprise a class of algorithms for learning properties of low-energy quantum states using a quantum computer, with particular relevance for molecular electronic structure calculations [3] [9]. The core principle involves constructing and diagonalizing an effective Hamiltonian within a carefully chosen subspace of the full quantum state space.

The Partitioned Quantum Subspace Expansion (PQSE) algorithm represents an iterative generalization of QSE that uses a Krylov basis [3]. This approach connects a sequence of subspaces via their lowest energy states, offering improved numerical stability over single-step approaches in the presence of finite sampling noise—a critical consideration for implementation on real quantum hardware [3]. The method employs a variance-based criterion for determining optimal iterative sequences and requires only polynomial classical overhead in the subspace dimension.

For molecular systems, quantum subspace methods establish rigorous complexity bounds and convergence guarantees, characterizing the relationship between subspace dimension, basis set selection, and solution accuracy for ground and excited state calculations [9]. The framework incorporates realistic noise models and provides performance predictions for near-term quantum devices, analyzing trade-offs between circuit depth, measurement overhead, and solution quality while identifying optimal operating regimes for different molecular systems.

Application Protocols

Protocol 1: Gibbs Free Energy Calculation for Prodrug Activation

Background: Prodrug activation strategies, particularly those based on carbon-carbon (C-C) bond cleavage, represent innovative approaches to targeted drug delivery [10]. Accurate calculation of the Gibbs free energy profile for these reactions is essential for predicting activation kinetics under physiological conditions.

Experimental Workflow:

System Preparation: Select key molecular structures along the reaction coordinate for C-C bond cleavage. For β-lapachone prodrug analysis, this involves five critical molecules during the cleavage process [10].

Active Space Selection: Employ active space approximation to simplify the quantum chemical region into a manageable two-electron/two-orbital system, reducing the problem to a 2-qubit implementation on superconducting quantum devices [10].

Wavefunction Preparation: Utilize the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) framework with a hardware-efficient ( R_y ) ansatz with a single layer as the parameterized quantum circuit [10].

Energy Calculation: Perform single-point energy calculations incorporating solvation effects using the polarizable continuum model (PCM) to simulate physiological conditions [10].

Free Energy Profiling: Compute Gibbs free energy differences between molecular states along the reaction pathway to determine activation energy barriers.

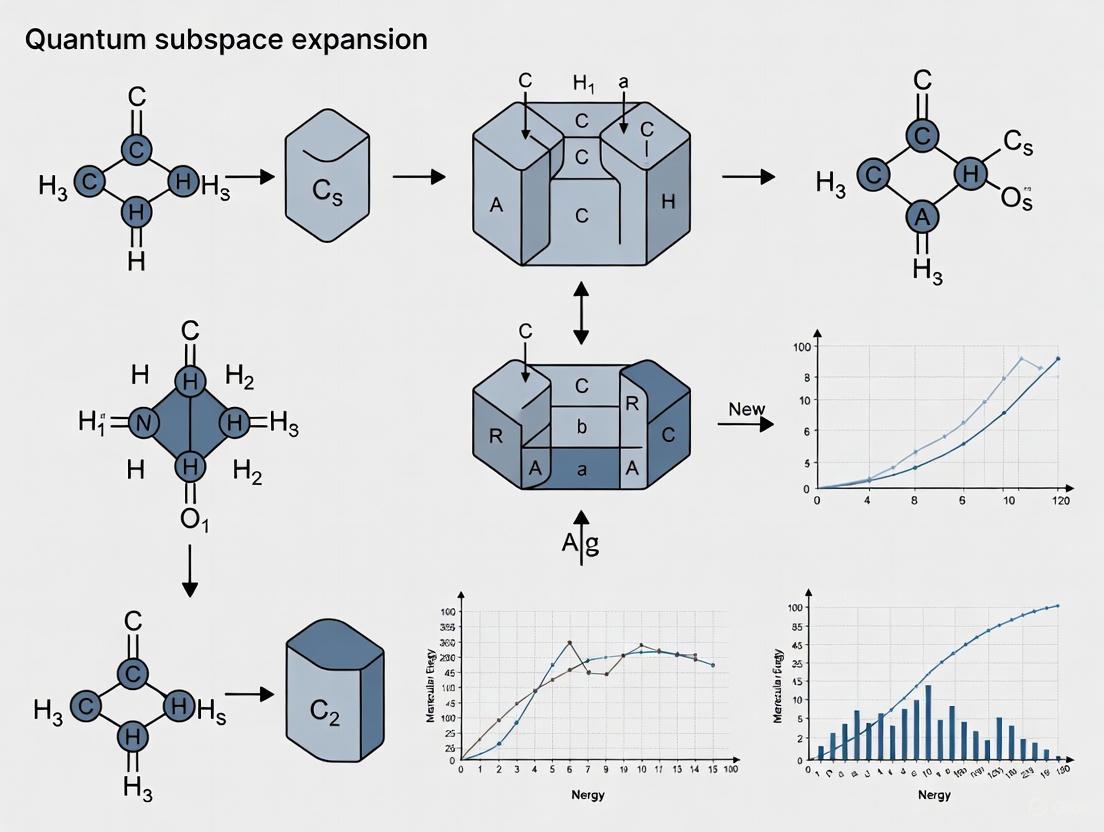

Figure 1: Workflow for prodrug activation energy calculation using a hybrid quantum-classical approach.

Key Considerations: The 6-311G(d,p) basis set is recommended for balanced accuracy and computational efficiency. Classical reference calculations using Hartree-Fock (HF) and Complete Active Space Configuration Interaction (CASCI) methods provide benchmarks for quantum computation results [10].

Protocol 2: Covalent Inhibitor Binding Analysis

Background: Covalent inhibitors, such as Sotorasib targeting the KRAS G12C mutation in cancers, represent a growing class of therapeutics that form covalent bonds with their protein targets [10]. Simulating these interactions requires precise modeling of bond formation energetics.

Experimental Workflow:

System Setup: Prepare the protein-ligand complex structure, focusing on the covalent binding site and surrounding residues.

QM/MM Partitioning: Implement a hybrid quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics (QM/MM) scheme where the covalent bond formation region is treated quantum mechanically while the remainder of the system is handled classically.

Force Calculation: Implement a hybrid quantum computing workflow for molecular forces during QM/MM simulation [10].

Binding Energy Calculation: Compute the interaction energies between the inhibitor and target protein, focusing on the covalent bond formation process.

Validation: Compare results with experimental binding affinity data and classical simulation methods where available.

Figure 2: Workflow for covalent inhibitor binding analysis using QM/MM and quantum computing.

Key Considerations: The QM region should include all atoms directly involved in the covalent bond formation and adjacent residues critical to the binding interaction. For KRAS G12C inhibitors, this includes the cysteine residue and surrounding pocket [10].

Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Quantum Subspace Expansion in Drug Discovery

| Category | Item | Function/Application | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantum Algorithms | Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) [10] | Ground state energy calculation | Uses parameterized quantum circuits with classical optimization |

| Quantum Subspace Expansion (QSE) [3] [5] | Excited state calculations and error mitigation | Builds Krylov subspace for diagonalization | |

| Partitioned QSE (PQSE) [3] | Iterative subspace expansion | Improved stability against sampling noise | |

| Classical Computational Methods | Density Functional Theory (DFT) [11] [10] | Reference molecular energy calculations | Multiple functionals (76+) and basis sets available |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) [12] | Conformational sampling and binding free energy | MM-PBSA, LIE, and alchemical methods | |

| Polarizable Continuum Model (PCM) [10] | Solvation energy calculation | Critical for physiological condition simulation | |

| Datasets & Libraries | MultiXC-QM9 Dataset [11] | Benchmarking and training | Molecular energies with 76 DFT functionals and 3 basis sets |

| Quantum Chemistry Packages | Hamiltonian generation and basis set management | TenCirChem [10] and other specialized software | |

| Error Mitigation | Readout Error Mitigation [10] | Measurement error correction | Standard technique for noisy quantum devices |

| Classical Shadows [5] | Efficient measurement protocol | Reduces required measurement resources |

Data Presentation and Analysis

Performance Benchmarks

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Computational Methods for Molecular Energy Calculations

| Method | Computational Scaling | Typical Accuracy | Key Advantages | Implementation Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical DFT | O(N³) to O(Nâ´) [8] | Chemical accuracy for many systems [10] | Well-established, reliable for medium systems | Struggles with strong correlation, large systems |

| Quantum Subspace Expansion | Polynomial in subspace dimension [9] | Approaching chemical accuracy [5] | Theoretical convergence guarantees, noise resilience | Measurement overhead, basis selection critical |

| Partitioned QSE | Polynomial overhead [3] | Improved stability in noise [3] | Parameter-free, enhanced numerical stability | Additional classical processing required |

| VQE-based Approaches | Circuit depth dependent [10] | Varies with ansatz choice [10] | Suitable for near-term devices, flexibility | Optimization challenges, barren plateaus |

| MM-PBSA (Classical) | O(N²) for PB solver [12] | ~2-3 kcal/mol for binding [12] | Efficient for large systems, implicit solvent | Limited accuracy for charged systems |

Case Study: Quantum Computing Pipeline for Real-World Drug Discovery

Recent work demonstrates a hybrid quantum computing pipeline applied to two critical drug discovery challenges [10]:

Prodrug Activation Analysis: Implementation of quantum computations for C-C bond cleavage in β-lapachone prodrugs, achieving consistent results with wet lab validation. The approach combined active space approximation with the ddCOSMO solvation model, demonstrating the viability of quantum computations for simulating covalent bond cleavage relevant to prodrug activation [10].

Covalent Inhibition Study: Application to KRAS G12C inhibition by Sotorasib, implementing a hybrid quantum computing workflow for molecular forces during QM/MM simulation. This approach enables detailed examination of covalent inhibitor binding mechanisms that are crucial in cancer therapy [10].

The pipeline demonstrated particular advantages for simulating covalent bonding interactions, transitioning quantum computing applications from theoretical models to tangible drug design problems [10].

Technical Validation and Error Mitigation

Accurate technical validation is essential for reliable quantum computations in drug discovery. The following approaches are recommended:

Classical Benchmarks: Compare quantum results with high-accuracy classical methods like CASCI and DFT for small systems where exact solutions are known [10].

Statistical Error Characterization: Implement rigorous statistical error analysis accounting for data covariances, particularly when using informationally complete measurements like classical shadows [5].

Regularization Techniques: Apply singular value decomposition (SVD) with regularization to address ill-conditioning in overlap matrices, discarding smallest singular values to stabilize calculations [5].

For the prodrug activation case study, researchers calculated atomization energy distributions across different basis sets (SZ, DZP, TZP) and observed expected trends where TZP and DZP basis sets produced similar results while SZ basis sets showed relatively different distributions [11]. Error distribution analysis for reaction energies demonstrated that errors typically follow a normal distribution with the majority of reactions exhibiting relatively small error scales due to error cancellation effects [11].

Large-scale implementations of quantum subspace expansion with classical shadows have been successfully demonstrated for systems of up to 80 qubits, accurately recovering ground state energies while effectively mitigating local order parameters [5]. These implementations required substantial measurement resources (32,768 randomized bases per circuit and 4.3×10¹¹ to 5.6×10¹³ Pauli traces) but established viable paths to overcoming measurement overhead through rigorous error characterization [5].

How QSE Complements and Enhances Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE)

Calculating molecular energies is a fundamental challenge in chemistry with profound implications for drug discovery and materials science. The Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) has emerged as a leading algorithm for near-term quantum computers to tackle this problem, operating by variationally optimizing a parameterized quantum circuit (ansatz) to find the ground state energy of a molecular Hamiltonian [13] [14]. Despite its promise, VQE faces significant practical limitations: its accuracy is constrained by the expressive power of the chosen ansatz, and its trainability is hampered by hardware noise, statistical errors, and the barren plateau phenomenon [15] [16]. These challenges become increasingly severe with molecular size, limiting VQE's practical application.

Quantum Subspace Expansion (QSE) provides a powerful post-processing technique that complements and enhances VQE by systematically improving its results. This hybrid approach allows researchers to balance quantum and classical computational resources effectively [15]. By building upon a VQE-prepared reference state, QSE can generate more accurate ground and excited state energies without increasing quantum circuit depth, thus mitigating some core limitations of standalone VQE implementations. This application note details the methodology, performance, and implementation protocols for integrating QSE with VQE in molecular energy calculations.

Theoretical Foundation: VQE and QSE Synergy

Variational Quantum Eigensolver Fundamentals

The VQE algorithm is a hybrid quantum-classical approach that leverages the variational principle to estimate the ground state energy of a molecular Hamiltonian. The algorithm follows these key steps:

- Hamiltonian Formulation: The molecular electronic Hamiltonian is transformed into a second-quantized form and then mapped to a qubit representation using techniques such as the Jordan-Wigner or parity transformation [13] [17].

- Ansatz Preparation: A parameterized quantum circuit (ansatz), such as the Unitary Coupled Cluster (UCC) or hardware-efficient ansatz, prepares a trial state (|\Psi(\vec{\theta})\rangle) from an initial reference state (typically Hartree-Fock) [13] [18].

- Measurement and Optimization: The expectation value (\langle \Psi(\vec{\theta})|H|\Psi(\vec{\theta})\rangle) is measured on quantum hardware, and a classical optimizer adjusts parameters (\vec{\theta}) to minimize this energy [14].

The accuracy of VQE is fundamentally limited by the ansatz's ability to represent the true ground state. Deep, expressive ansätze often require circuit depths incompatible with current noisy quantum devices, while shallow ansätze may lack the representational power for strongly correlated systems [19].

Quantum Subspace Expansion Framework

QSE enhances VQE by performing a classical diagonalization of the Hamiltonian in a carefully constructed subspace around the VQE solution. The general QSE procedure, following the VQE optimization, is:

- Subspace Construction: Generate a set of basis states ({|\Psii\rangle}) that span a subspace (\mathcal{CS}K). This can be a fine-grained Krylov subspace formed by applying Pauli strings (Pj) to the VQE state: (|\Psii\rangle = Pj|\Psi_{\text{VQE}}\rangle) [15].

- Matrix Element Measurement: Use the quantum computer to measure the matrix elements of the Hamiltonian ((H{ij} = \langle\Psii|H|\Psij\rangle)) and overlap ((S{ij} = \langle\Psii|\Psij\rangle)) operators within this subspace.

- Classical Diagonalization: Solve the generalized eigenvalue problem (H\vec{c} = ES\vec{c}) on a classical computer to obtain refined energy estimates and wavefunctions within the subspace [15] [16].

This approach increases the expressivity of the final wavefunction without complicating the quantum circuit training, as the diagonalization is performed classically [15]. The subspace expansion effectively captures additional electron correlation effects missing from the original VQE state.

Performance Comparison and Quantitative Analysis

Multiple studies demonstrate that the VQE-QSE combination delivers superior performance compared to standalone VQE, particularly for more complex molecular systems and in the presence of hardware noise.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of VQE and VQE-QSE for Molecular Ground State Calculations

| Molecule | Method | Ansatz/Protocol | Energy Accuracy (Absolute Error) | Key Performance Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H(_2)/Small Systems | Standalone VQE | UCCSD | Varies (exact for minimal systems) | Baseline for comparison [13] |

| VQE-QSE | UCCSD with FGKS expansion | Improved | Systematically approaches exact solution [15] | |

| H(_{24}) (STO-3G) | Fragment-Based VQE | FMO/VQE with UCCSD | 0.053 mHa | Reduced qubit requirement [20] |

| Stretched H(_6) | ADAPT-VQE | QEB-ADAPT | ~1000+ CNOT gates for chemical accuracy | Prone to local minima, over-parameterization [19] |

| Stretched H(_6) | Overlap-ADAPT-VQE | Overlap-guided compact ansatz | Chemically accurate with fewer operators | Avoids energy plateaus, more compact circuits [19] |

| General Performance in Noise | Standalone VQE | Various | Degraded by noise and barren plateaus | Optimization becomes difficult with system size [15] [16] |

| General Performance in Noise | VQE-QSE (PIQAE) | Balanced ansatz depth ((L)) & expansion moment ((K)) | Order of magnitude improvement per site demonstrated on IBM QPUs | Robustness against noise; accuracy tunable via (L) and (K) [15] |

Table 2: QSE Applications Beyond Ground State Energy Calculation

| Application | QSE Variant | System Studied | Key Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Excited State & Band Structure Calculation | Standard QSE | Silicon crystal quasiparticle bands | Enabled calculation of excited states from VQE ground state [16] |

| Scalable Ground State Calculation | QSE with Quantum-Selected CI (QSCI) | -- | Avoids full VQE optimization; uses quantum sampling to select configurations [16] |

| Noise-Resilient Calculation | Paired IQAE (PIQAE) | 1D/2D Ising models on ibmq_quito/guadalupe | Effective noise mitigation via optimal subspace selection (e.g., based on overlap matrix trace) [15] |

Experimental Protocols

Core VQE-QSE Workflow Protocol

This protocol outlines the essential steps for implementing the combined VQE-QSE method for molecular ground state energy calculation.

Step 1: Molecular Hamiltonian Preparation

- Input: Molecular geometry (atomic species and coordinates), basis set (e.g., STO-3G, 6-31G).

- Procedure:

- Classically compute molecular integrals (one- and two-electron integrals in the chosen basis set) using quantum chemistry packages (e.g., PySCF via OpenFermion) [19].

- Form the second-quantized electronic Hamiltonian ( \hat{H} = \sum{pq} h{pq} ap^\dagger aq + \frac{1}{2} \sum{pqrs} h{pqrs} ap^\dagger aq^\dagger ar as ) [13] [20].

- Map the fermionic Hamiltonian to a qubit Hamiltonian using a transformation (e.g., Jordan-Wigner, parity) [13] [16]. The result is a Pauli string representation: ( H = \sumi wi P_i ).

Step 2: VQE Optimization

- Input: Qubit Hamiltonian, choice of ansatz (e.g., UCCSD, hardware-efficient), initial parameters.

- Procedure:

- Prepare Initial State: Prepare the Hartree-Fock state ( |0\rangle ) on the quantum computer.

- Construct Ansatz Circuit: Implement the parameterized ansatz circuit ( U(\vec{\theta}) ). For UCCSD, this involves Trotterized exponentials of fermionic excitation operators [13].

- Measure Expectation Value: Estimate ( \langle H \rangle = \langle 0| U^\dagger(\vec{\theta}) H U(\vec{\theta}) |0\rangle ) by measuring the expectation values of all Pauli terms ( Pi ). Use grouping strategies (e.g., qubit-wise commuting) to reduce measurement overhead [17].

- Classical Optimization: Use a classical optimizer (e.g., BFGS) to minimize ( \langle H \rangle ) with respect to parameters ( \vec{\theta} ). The optimized state is ( |\Psi{\text{VQE}}\rangle = U(\vec{\theta}^*)|0\rangle ) [18].

Step 3: Quantum Subspace Expansion

- Input: Optimized VQE state ( |\Psi_{\text{VQE}}\rangle ), subspace definition.

- Procedure:

- Define Subspace Basis: Choose a set of basis states for expansion. A common choice is the fine-grained Krylov subspace, where basis vectors are ( |\Phij\rangle = \hat{P}j |\Psi{\text{VQE}}\rangle ) and ( \hat{P}j ) are Pauli strings from a predefined set (e.g., all Paulis up to a certain weight ( K )) [15].

- Measure Subspace Matrices: On the quantum computer, measure the matrix elements of the Hamiltonian ( H{ij} = \langle\Phii|H|\Phij\rangle ) and the overlap ( S{ij} = \langle\Phii|\Phij\rangle ). This does not require deep controlled circuits but can involve a substantial number of measurements [15].

- Classically Diagonalize: Solve the generalized eigenvalue problem ( \mathbf{H} \vec{c} = E \mathbf{S} \vec{c} ) on a classical computer. The lowest eigenvalue ( E_0 ) is the QSE-refined ground state energy estimate [15] [16].

Diagram 1: VQE-QSE Hybrid Algorithm Workflow. The process integrates quantum (red/blue) and classical (yellow/green) computation stages, beginning with Hamiltonian preparation and culminating in a refined energy estimate via subspace diagonalization.

Advanced Protocol: Noise-Aware PIQAE

For calculations on real noisy hardware, the Paired Iterative Quantum-Assisted Eigensolver (PIQAE) protocol provides enhanced robustness [15].

Procedure:

- Balance Resources: Choose a VQE ansatz depth ( L ) compatible with hardware error rates. A shallower, more noise-resilient ansatz is often preferable.

- Perform VQE: Run the standard VQE optimization with the chosen ansatz.

- Iterative Expansion: Expand the subspace up to a moment ( K ), limited by the classical and quantum computational budget (e.g., number of measurements).

- Noise Mitigation and Subspace Selection:

- Measure the overlap matrix ( \mathbf{S} ) under noise.

- Compute its trace. As noise increases, the trace deviates from its noiseless value (which equals the subspace dimension).

- Use the trace to select the optimal subspace dimension ( \mathcal{M}_o ) to truncate the noisy matrices before diagonalization, preventing unphysical energy estimates [15].

- Optional Error Mitigation: Apply additional error mitigation techniques (e.g., probabilistic error cancellation) to the measurement results of ( H{ij} ) and ( S{ij} ) for further accuracy improvement [15].

Table 3: Key Software Tools and Computational Resources for VQE-QSE Implementation

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to VQE-QSE |

|---|---|---|---|

| OpenFermion | Software Library | Manipulation of fermionic Hamiltonians and mapping to qubits [19]. | Prepares the qubit Hamiltonian from molecular data. Essential first step. |

| Qiskit / PennyLane | Quantum Computing SDK | Construction and simulation of quantum circuits, execution on simulators/hardware [13] [14]. | Implements the VQE ansatz circuit, manages measurement, and interfaces with classical optimizers. |

| PySCF | Quantum Chemistry Package | Computes molecular integrals and performs classical electronic structure calculations [19]. | Generates the one- and two-electron integrals required to build the second-quantized Hamiltonian. |

| IBM Quantum / AWS Braket | Cloud QPU Access | Provides access to real noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices [15]. | Platform for running the quantum steps (state preparation and measurement) of the VQE-QSE algorithm. |

| BFGS / SPSA Optimizers | Classical Optimization Algorithm | Finds parameters that minimize the energy cost function [18]. | Critical for the VQE parameter optimization loop. Gradient-based optimizers like BFGS are often preferred [18]. |

| Fine-Grained Krylov Subspace | Mathematical Subspace | Defines the basis for the QSE expansion [15]. | The specific choice of subspace (e.g., using Pauli strings) directly impacts the accuracy and cost of the QSE refinement. |

The integration of Quantum Subspace Expansion with the Variational Quantum Eigensolver represents a significant advancement in quantum computational chemistry. This synergistic approach effectively addresses key limitations of standalone VQE—limited ansatz expressivity and susceptibility to noise—by offloading additional complexity to efficient classical post-processing. The structured protocols and performance data presented herein provide researchers and drug development professionals with a practical framework for implementing these hybrid algorithms. As quantum hardware continues to evolve, the VQE-QSE paradigm is poised to play an increasingly vital role in enabling high-accuracy simulation of complex molecular systems, accelerating the discovery of new therapeutic agents and functional materials.

The Role of Krylov Subspaces in Building an Expansive Computational Basis

Quantum subspace expansion (QSE) represents a powerful class of hybrid quantum-classical algorithms designed to overcome the limitations of variational methods for molecular energy calculations. Unlike variational quantum eigensolver (VQE) approaches that require challenging parameter optimizations, QSE methods formulate the problem as a generalized eigenvalue problem within a carefully constructed subspace of the full Hilbert space [21] [22]. The core mathematical framework involves projecting the molecular Hamiltonian into a smaller subspace spanned by a set of basis states, then solving the eigenvalue problem classically to obtain approximate ground and excited state energies [22]. This approach has demonstrated particular promise for near-term and early fault-tolerant quantum hardware by exchanging quantum circuit depth for additional measurements [3].

Among various subspace constructions, Krylov subspaces have emerged as particularly powerful due to their proven convergence properties and foundation in classical numerical analysis [3] [21]. A Krylov subspace of dimension D is typically generated from an initial reference state |ψ₀⟩ through repeated applications of the Hamiltonian H: ð’¦ = span{|ψ₀⟩, H|ψ₀⟩, H²|ψ₀⟩, ..., Há´°â»Â¹|ψ₀⟩} [22]. The exceptional value of this construction lies in its exponential convergence toward the true ground state energy as the subspace dimension increases, a property well-established in classical numerical mathematics that carries over to quantum implementations [21] [22]. For quantum chemistry applications, this enables systematically improvable approximations to molecular energies without exponentially growing quantum resource requirements.

Table: Comparison of Quantum Computational Approaches for Molecular Energy Calculations

| Method | Key Principle | Convergence Guarantees | Quantum Resource Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) | Parametric circuit optimization | Limited; depends on ansatz and optimization | Moderate circuit depth, many measurements |

| Quantum Phase Estimation (QPE) | Quantum Fourier transform on phase information | Theoretical guarantees with error correction | Very high circuit depth, fault tolerance needed |

| Quantum Krylov Subspace Diagonalization | Projected eigenvalue problem in constructed subspace | Exponential with subspace dimension (theoretical) | Low-moderate circuit depth, many measurements |

| Partitioned Quantum Subspace Expansion (PQSE) | Iterative Krylov subspace construction | Improved numerical stability with exponential convergence | Same quantum resources as QSE, additional classical processing |

Krylov Subspace Fundamentals and Theoretical Framework

Mathematical Foundation of Krylov Methods

The theoretical foundation of Krylov subspace methods in quantum computing mirrors their established classical counterparts while addressing quantum-specific challenges. In classical numerical mathematics, the Lanczos algorithm represents the archetypal Krylov method for eigenvalue problems, generating an orthonormal basis for the Krylov subspace through a three-term recurrence relation [23] [24]. This elegant mathematical structure ensures that the Hamiltonian becomes tridiagonal in the Krylov basis, significantly simplifying the eigenvalue solution while maintaining exponential convergence properties [24]. The power of this approach stems from the global operator nature of Hamiltonian powers, which efficiently explore the regions of Hilbert space most relevant to the low-energy spectrum.

The transfer of these methods to quantum computers introduces both opportunities and challenges. Quantum Krylov Diagonalization (KQD) leverages the quantum computer's ability to handle exponentially large state spaces while avoiding the memory limitations that constrain classical approaches for large quantum systems [21]. The core mathematical problem solved by KQD is the generalized eigenvalue equation H̃c = EŜc, where H̃ is the Hamiltonian projected into the Krylov subspace with elements H̃ⱼₖ = ⟨ψⱼ|H|ψₖ⟩, and Ŝ is the overlap matrix with elements Ŝⱼₖ = ⟨ψⱼ|ψₖ⟩ [21]. The eigenvectors c provide the coefficients for the optimal linear combination of basis states that approximates the true molecular eigenstates.

For molecular energy calculations, a critical theoretical advantage emerges from the variational property of subspace methods: the ground state energy obtained by diagonalizing the projected Hamiltonian is guaranteed to be an upper bound to the true ground state energy [24]. This variational foundation ensures systematic improvability and provides a valuable diagnostic for method accuracy. Furthermore, the accuracy of the ground state approximation can be quantified by the variance of the Hamiltonian in the trial state, with zero variance indicating an exact eigenstate [22].

Krylov Basis Construction Methods

Several technical approaches have been developed for constructing Krylov subspaces on quantum hardware, each with distinct advantages for molecular applications:

Unitary Krylov Spaces: Generated through real-time evolutions Uʲ|ψ₀⟩ = eâ»â±Hʲᵈᵗ|ψ₀⟩, these subspaces leverage the natural dynamics of quantum systems and are particularly suitable for near-term devices due to their implementability with relatively shallow circuits [21].

Power Krylov Spaces: Constructed from powers of the Hamiltonian Hʲ|ψ₀⟩, these subspaces directly mirror classical Krylov methods and can be implemented through qubitization techniques, though they typically require deeper circuits [22].

Chebyshev Krylov Spaces: Using Chebyshev polynomials Tⱼ(H)|ψ₀⟩ as basis states provides numerical advantages and enables efficient implementation through Quantum Signal Processing (QSP), making this approach particularly valuable for fault-tolerant implementations [23].

The choice of construction method involves trade-offs between circuit depth, measurement requirements, and numerical stability. For molecular systems with specific symmetry properties, customized approaches that preserve symmetries can significantly enhance efficiency and accuracy.

Advanced Krylov Techniques and Protocol Implementation

Partitioned Quantum Subspace Expansion (PQSE)

The Partitioned Quantum Subspace Expansion (PQSE) represents a significant advancement in addressing the primary limitation of standard Krylov methods: numerical instability arising from ill-conditioned overlap matrices [3] [22]. As the Krylov dimension increases, higher-order basis states become nearly linearly dependent due to the mathematical properties of power iteration, causing the overlap matrix Ŝ to become ill-conditioned and amplifying noise in measured matrix elements [22]. PQSE addresses this challenge through an iterative partitioning strategy that breaks a large QSE problem into a sequence of smaller, better-conditioned subproblems.

The PQSE protocol operates by connecting a sequence of subspaces through their lowest-energy states, with the output of one small QSE instance serving as input to the next iteration [3] [22]. This approach maintains the same quantum resource requirements as standard QSE while introducing additional classical processing with polynomial overhead in the subspace dimension [3]. The partioning strategy is guided by a variance-based criterion for determining effective iterative sequences, with numerical demonstrations showing substantially improved numerical stability in the presence of finite sampling noise compared to both standard QSE and thresholded QSE (TQSE) [22].

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Quantum Krylov Experiments

| Research Reagent | Function in Experiment | Implementation Considerations | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Krylov Subspace Basis States | Forms the computational basis for diagonalization | Choice between unitary, power, or Chebyshev constructions affects circuit depth and measurement requirements | |

| Overlap Matrix (Ŝ) | Encodes linear dependencies between basis states | Ill-conditioning requires regularization techniques; measured via swap tests or Hadamard tests | |

| Projected Hamiltonian (H̃) | Reduced Hamiltonian for classical diagonalization | Matrix elements measured through quantum expectation value estimation | |

| Reference State | ψ₀⟩ | Initial state for Krylov basis generation | Typically Hartree-Fock state for molecular systems; affects convergence rate |

| Time Evolution Operator eâ»â±Hᵈᵗ | Generates unitary Krylov basis states | Implemented through Trotterization or more advanced product formulas; depth depends on accuracy requirements |

Experimental Protocol: Quantum Krylov Subspace Diagonalization

The following protocol details the implementation of Quantum Krylov Subspace Diagonalization for molecular energy calculations, based on established methodologies from recent experimental demonstrations [23] [21].

Step 1: System Preparation and Reference State Initialization

- Prepare the molecular Hamiltonian H in qubit representation using Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev transformation. For the water molecule (Hâ‚‚O) in a cc-pVDZ basis with 4 electrons in 4 molecular orbitals, this results in a 16-term Hamiltonian [23].

- Initialize the reference state |ψ₀⟩, typically the Hartree-Fock state, which can be prepared through a simple quantum circuit applying X gates to qubits corresponding to occupied orbitals.

- For systems with conserved quantities (e.g., particle number, total spin), exploit these symmetries to simplify circuits and improve convergence [21].

Step 2: Krylov Basis Construction

- Select the Krylov subspace dimension D based on desired accuracy and available quantum resources. For initial experiments, D=4-8 provides reasonable accuracy while managing measurement costs.

- Generate basis states using the chosen construction method:

- For near-term hardware, focus on minimizing circuit depth through optimization techniques and hardware-aware compilation.

Step 3: Quantum Measurement of Matrix Elements

- Measure all elements of the overlap matrix Ŝⱼₖ = ⟨ψⱼ|ψₖ⟩ and projected Hamiltonian H̃ⱼₖ = ⟨ψⱼ|H|ψₖ⟩ using efficient quantum circuits.

- Employ symmetry relations to reduce measurement requirements: for exact time evolutions, H̃ⱼₖ = ⟨ψ₀|HUáµâ»Ê²|ψ₀⟩, enabling measurement with a single time evolution [21].

- For each matrix element, perform sufficient measurement shots to achieve desired statistical precision, considering the trade-off between measurement cost and accuracy.

Step 4: Classical Post-Processing and Diagonalization

- Construct the matrices H̃ and Ŝ from measured matrix elements, applying error mitigation techniques to address measurement noise and hardware errors.

- Solve the generalized eigenvalue problem H̃c = EŜc using classical computational resources.

- Apply regularization techniques if Ŝ is ill-conditioned, such as truncated singular value decomposition with an appropriate threshold [24].

- Extract the ground state energy Eâ‚€ as the lowest eigenvalue, and excited states from higher eigenvalues if desired.

Step 5: Validation and Error Analysis

- Compute the energy variance var(H) = ⟨H²⟩ - ⟨H⟩² for the obtained ground state to assess accuracy, with near-zero variance indicating a good approximation to a true eigenstate [22].

- Perform convergence analysis with respect to Krylov dimension D to ensure sufficient basis size.

- For partitioned approaches (PQSE), iterate the process using the obtained ground state as a new reference until convergence criteria are satisfied [3].

Measurement-Efficient Variants and Error Mitigation

Recent advances in quantum Krylov methods have focused on addressing the challenging measurement requirements through algorithmic innovations. The measurement-efficient quantum Krylov subspace diagonalization approach reduces the number of required measurements by expressing the product of power and Gaussian functions of the Hamiltonian as an integral of real-time evolution, evaluable through Monte Carlo sampling on quantum computers [24]. This approach can reduce measurement costs by orders of magnitude compared to standard implementations while maintaining accuracy comparable to classical Lanczos algorithms at the same subspace dimension [24].

For error mitigation in near-term implementations, several strategies have proven effective:

- Symmetry verification: Exploit conserved quantities (e.g., particle number) to detect and mitigate errors that violate these symmetries [21].

- Regularization techniques: Address ill-conditioned overlap matrices through truncated singular value decomposition or Tikhonov regularization, with theoretical guarantees ensuring variational bounds remain valid [24].

- Noise-aware algorithms: Design circuits specifically to minimize error accumulation, such as using circuits that preserve the "vacuum state" up to a calculable phase to avoid controlled time evolutions [21].

Applications in Molecular Energy Calculations

Practical Implementation for Molecular Systems

Quantum Krylov subspace methods have demonstrated significant potential for practical molecular energy calculations, with several experimental implementations showcasing their capabilities. For the water molecule (Hâ‚‚O) in a cc-pVDZ basis with an active space of 4 electrons in 4 molecular orbitals, the Krylov approach enables accurate ground state energy estimation with relatively modest quantum resources [23]. The protocol involves constructing the Krylov subspace using Chebyshev polynomials Tâ±¼(H)|ψ₀⟩ applied to the Hartree-Fock reference state, then solving the generalized eigenvalue problem to obtain the ground state approximation |Ψ₀⟩ = ∑ₖcâ‚–â°Tâ‚–(H)|ψ₀⟩ [23].

Beyond ground state energies, Krylov methods facilitate the efficient calculation of molecular properties through reduced density matrices. For the one-particle reduced density matrix with elements γₚₚ' = ⟨Ψ₀|aₚ†aₚ'|Ψ₀⟩, specialized measurement protocols based on Quantum Signal Processing can achieve constant scaling with respect to Krylov dimension D, dramatically improving over the quadratic scaling of naive measurement approaches [23]. This capability is essential for computing molecular properties such as dipole moments, bond orders, and other electronic structure indicators directly relevant to drug development.

For drug discovery applications, where accurate molecular energy calculations inform binding affinity predictions and reactivity assessments, the numerical stability and systematic improvability of Krylov methods offer significant advantages over purely variational approaches. The ability to compute both ground and excited states within the same framework further enables studies of photochemical properties and reaction pathways relevant to pharmaceutical development.

Performance Analysis and Resource Requirements

The performance of quantum Krylov methods is characterized by exponential convergence toward the true ground state energy with increasing subspace dimension, providing a systematic path to higher accuracy without increasing quantum circuit depth [21] [22]. This convergence behavior has been experimentally demonstrated on quantum processors for systems of up to 56 qubits, showing that quantum diagonalization algorithms can complement classical counterparts even in the pre-fault-tolerant era [21].

The primary resource requirements for quantum Krylov methods include:

- Circuit depth: Scales with the complexity of time evolution operators, typically implemented through Trotterization with depth depending on the molecular Hamiltonian and desired accuracy.

- Measurement count: Grows with the square of subspace dimension D² for naive implementations, but advanced techniques can substantially reduce this scaling [24].

- Classical processing: Involves solving a D×D generalized eigenvalue problem, with polynomial scaling in D that is typically manageable for classically tractable subspace dimensions (D < 100).

For the Partitioned Quantum Subspace Expansion (PQSE), the quantum resource requirements remain identical to standard QSE, while classical processing overhead increases polynomially but provides substantially improved numerical stability and ability to reach larger effective Krylov dimensions [3] [22]. This trade-off favors PQSE for applications where measurement noise rather than quantum circuit performance represents the primary limitation, as is often the case for current quantum hardware.

Table: Performance Comparison of Quantum Krylov Methods for Molecular Systems

| Method | Convergence Rate | Measurement Cost | Numerical Stability | Circuit Depth Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard QSE | Exponential with D | O(D²) for naive implementation | Poor at large D due to ill-conditioning | Moderate (Trotterized evolution) |

| TQSE (Thresholded) | Exponential up to critical D | Similar to standard QSE | Improved via SVD truncation | Moderate (Trotterized evolution) |

| PQSE (Partitioned) | Exponential with effective dimension | Same as QSE, better stability | Substantially improved via partitioning | Moderate (Trotterized evolution) |

| Measurement-Efficient QKSD | Comparable to classical Lanczos | Orders of magnitude reduction | Good with regularization | Moderate to high (depends on implementation) |

Krylov subspace methods represent a foundational approach for building expansive computational bases in quantum computational chemistry, offering rigorous convergence guarantees and practical implementability on emerging quantum hardware. The iterative structure of Partitioned Quantum Subspace Expansion addresses the critical challenge of numerical instability while maintaining exponential convergence, enabling larger effective Krylov dimensions and higher accuracy for molecular energy calculations [3] [22]. For drug development professionals and researchers, these methods provide a systematically improvable path toward predictive quantum chemistry simulations without requiring fault-tolerant quantum computing.

Future developments in quantum Krylov methods will likely focus on further reducing measurement costs, enhancing error mitigation techniques, and developing problem-specific basis constructions that leverage molecular symmetries and structure. As quantum hardware continues to advance, the integration of Krylov subspace methods with fault-tolerant building blocks such as Quantum Signal Processing will enable increasingly accurate simulations of complex molecular systems relevant to pharmaceutical development and materials design.

Quantum Subspace Expansion (QSE) is a computational technique in quantum chemistry that enables the calculation of molecular excited state energies from a pre-computed ground state. This method is particularly valuable for near-term quantum computers, as it provides a pathway to extract excited state information and additional correlation energy beyond what is achievable with a standalone Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) calculation. The core idea involves constructing a linear subspace of wavefunctions from a reference ground state, followed by the diagonalization of the molecular Hamiltonian within that subspace to obtain a set of energetically low-lying states [25] [4].

The process begins with a correlated ground state wavefunction, (|\Psi{0}\rangle), typically obtained using the VQE algorithm. A subspace is then created by applying a set of excitation operators to this ground state. Commonly, these are single- and double-electron excitation operators from the field of quantum chemistry: [ \hat{G}{i}^{a} = \hat{a}^{\dagger}{a}\hat{a}{i}, \quad \hat{G}{ij}^{ab} = \hat{a}^{\dagger}{a}\hat{a}^{\dagger}{b}\hat{a}{j}\hat{a}{i} ] where (i, j) denote occupied orbitals and (a, b) denote virtual orbitals in the reference state [26]. The resulting subspace vectors, ( |\Psi{j}^{k}\rangle = ck^{\dagger}c{j}|\Psi_0\rangle ), are not generally orthogonal, necessitating the solution of a generalized eigenvalue problem to find the optimal energy eigenvalues and eigenvectors within the subspace [25].

Theoretical Foundation: Overlap Matrix and Generalized Eigenvalue Problem

The Overlap Matrix (S)

The overlap matrix, S, is a central mathematical object in the QSE formalism. It quantifies the non-orthogonality of the basis vectors that span the constructed subspace. The matrix elements of S are defined as the inner products between these basis states [27]: [ S{jk}^{lm} = \langle \Psij^l | \Psik^m \rangle = \langle \Psi{0} | c{j}^\dagger c{l} c{m}^{\dagger}c{k} | \Psi_{0} \rangle ] In a quantum computation, this expectation value is measured on a quantum computer or simulator after mapping the fermionic operators to Pauli spin operators via a transformation such as Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev [25]. The overlap matrix is a square, positive definite matrix. If the basis vectors were orthonormal, S would be the identity matrix. However, the use of non-orthogonal basis vectors leads to off-diagonal elements, and the matrix's condition number (the ratio of its largest to smallest singular value) becomes a critical factor for the numerical stability of the subsequent eigenvalue solution [26] [27].

The Hamiltonian Matrix (H)

Simultaneously, the Hamiltonian matrix, H, is constructed within the same subspace. Its elements are the expectation values of the system's Hamiltonian, (\hat{H}), with respect to the subspace basis vectors [4]: [ H{jk}^{lm} = \langle\Psij^l \left| \hat{H} \right| \Psik^m\rangle = \langle \Psi{0} | c{j}^\dagger c{l} \hat{H}c{m}^{\dagger}c{k}|\Psi_{0}\rangle ] Like the overlap matrix, these matrix elements are also determined through quantum measurements.

The Generalized Eigenvalue Equation

The optimal energies and wavefunctions within the QSE subspace are found by solving the generalized eigenvalue equation [25] [4]: [ \mathbf{H}C = \mathbf{S}CE ] Here, (E) is a diagonal matrix containing the eigenvalues (which provide estimates for the ground and excited state energies), and (C) is the matrix of eigenvectors containing the expansion coefficients for the states in the chosen basis. This equation can be solved on a classical computer once the H and S matrices have been measured on the quantum processor.

Critical Analysis and Numerical Challenges

A significant challenge in practical QSE implementations is the numerical instability arising from the generalized eigenvalue problem. This instability is directly linked to the condition number of the overlap matrix, S [26].

- Ill-Conditioning and Sampling Errors: When the overlap matrix has a high condition number, it is termed "ill-conditioned." In this regime, small errors in the matrix elements of H and S—which are inevitable due to finite sampling (shot noise) on quantum hardware—can lead to large errors in the computed eigenvalues [26].

- Singularities and Thresholding: In severe cases, the overlap matrix can become nearly singular (i.e., its determinant is close to zero), preventing a standard numerical solution. A common technique to mitigate this is thresholding, where the smallest eigenvalues of the S matrix and their corresponding eigenvectors are discarded before solving the generalized eigenvalue problem in the remaining, more stable subspace. While this can restore solvability, it may also result in the loss of physically meaningful excited states from the calculated spectrum [26].

- Comparison with Alternative Methods: The instability of the generalized eigenvalue problem has motivated the development of alternative subspace methods that do not suffer from this issue. The quantum self-consistent Equation-of-Motion (q-sc-EOM) method, for example, uses an orthonormal set of excited wavefunctions, leading to an overlap matrix that is the identity matrix. This transforms the problem into a standard eigenvalue equation, which is inherently more robust to statistical sampling errors [26]. Another approach is the Partitioned Quantum Subspace Expansion (PQSE), which iteratively connects a sequence of smaller subspaces. This method has been shown to offer improved numerical stability over single-step QSE in the presence of finite sampling noise [3].

Experimental Protocol: QSE for Molecular Energy Calculation

The following protocol outlines the steps for performing a Quantum Subspace Expansion calculation to compute the ground and excited states of a molecule, using methane (CHâ‚„) in a minimal basis set as an example [25].

System Definition and Qubit Encoding

Step 1: Define the Molecular System

- Specify the molecular geometry, for example, using a Z-matrix.

- Select a basis set (e.g., STO-3G) and run a classical Restricted Hartree-Fock (RHF) calculation to obtain the electronic integrals.

- Freeze a subset of core orbitals to reduce the problem size.

Step 2: Qubit Encoding

- Map the fermionic Hamiltonian and the Hartree-Fock state to the qubit space using an encoding scheme such as Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev.

- Compress the resulting qubit Hamiltonian by discarding terms with negligible weights to reduce the number of required quantum measurements.

Ground State Preparation via VQE

Step 3: Prepare the Ground State Ansatz

- Select a parametrized quantum circuit (ansatz) capable of representing electron correlation. The Chemically Aware Unitary Coupled Cluster Singles and Doubles (UCCSD) ansatz is a common choice.

Step 4: Optimize the Ground State

- Use the VQE algorithm to find the parameters that minimize the energy expectation value of the qubit Hamiltonian. This can be done on a noiseless simulator for initial testing.

Subspace Expansion and Matrix Measurement

Step 5: Define the Expansion Operators

- Choose a set of operators to generate the subspace. For calculating spin-adapted excited states, singlet single excitation operators are a suitable and common starting point.

Step 6: Construct the QSE Matrices Computable

- Define a computational object that will handle the construction of the H and S matrices.

Step 7: Configure the Quantum Backend and Measurement Protocol

- Select a quantum backend (simulator or hardware). For shot-based simulations, define a measurement protocol that specifies the number of measurements (shots) per circuit.

Classical Post-Processing

Step 8: Run the QSE Algorithm and Solve the Generalized Eigenvalue Problem

- Execute the algorithm to measure all required matrix elements. Subsequently, solve the generalized eigenvalue problem ( \mathbf{H}C = \mathbf{S}CE ) on a classical computer.

- The resulting eigenvalues correspond to the QSE-corrected ground state energy and the energies of the captured excited states. The eigenvectors describe the wavefunctions of these states within the expanded subspace.

Workflow and Data Relationships

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and data flow of a typical Quantum Subspace Expansion calculation.

QSE Experimental Workflow

Advanced Methodologies and Error Mitigation

Handling Numerical Instability

To address the inherent instability of the generalized eigenvalue problem in QSE, several advanced methodologies have been developed:

- Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) and Thresholding: This is the primary technique for stabilizing the QSE calculation. The overlap matrix S is diagonalized via SVD (( \mathbf{S} = U \Sigma V^\dagger )). Singular values in ( \Sigma ) that fall below a pre-defined threshold are considered to represent numerical noise or linear dependencies and are discarded. The generalized eigenvalue problem is then projected and solved in the truncated subspace spanned by the retained singular vectors, which is numerically well-behaved [26] [5].

- Partitioned QSE (PQSE): This iterative generalization of QSE breaks a single, large Krylov subspace into a sequence of smaller, connected subspaces. By diagonalizing the Hamiltonian in each smaller subspace and using the lowest-energy state to initiate the next, PQSE can substantially alleviate numerical instability in a parameter-free manner, albeit with additional classical processing [3].

- Reformulation as a Constrained Optimization: Another approach reformulates the QSE problem as a constrained optimization problem, which allows for rigorous statistical error estimates and can avoid numerical instability associated with direct matrix inversion. This method has been successfully demonstrated in large-scale experiments using classical shadows for measurement [5].

Measurement Techniques

The efficient measurement of the H and S matrix elements is a significant bottleneck. Advanced measurement strategies can drastically reduce the required quantum resources.

- Classical Shadows: This technique uses informationally complete (IC) measurements, randomizing the measurement basis over many circuit executions. It allows for the efficient estimation of many observables (like all the matrix elements of H and S) from a single set of measurements, making it scalable to large systems (dozens of qubits) [5].

- Pauli Averaging: A more conventional shot-based protocol where the expectation values of the Pauli terms that make up the H and S matrices are measured directly and averaged [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The table below details the key computational "reagents" and their functions required to implement a QSE experiment.

| Item Name | Function in QSE Protocol | Specification Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Hamiltonian | Defines the quantum mechanical system and its energy levels; the operator to be diagonalized. | Generated from electronic structure integrals via a classical Hartree-Fock calculation [25]. |

| Qubit Mapping | Transforms the fermionic Hamiltonian and operators into a form executable on a qubit-based quantum processor. | Jordan-Wigner and Bravyi-Kitaev are common mappings [25] [4]. |

| VQE Ansatz | A parametrized quantum circuit that prepares an approximation of the true molecular ground state. | UCCSD is a chemically inspired, common choice. Other ansatzes like hardware-efficient can be used [25]. |

| Expansion Operator Set | A set of operators that generate the subspace when applied to the ground state. | Typically single and double excitations. Singlet singles ensure spin adaptation [26] [4]. |

| Quantum Backend/Simulator | The computational engine that executes the quantum circuits to measure expectation values. | Can be a noiseless simulator (e.g., Qulacs) for algorithm development, or shot-based simulators/hardware for realistic results [25] [4]. |

| Measurement Protocol | The strategy for estimating expectation values from quantum circuit executions. | Protocols include Pauli Averaging (direct measurement) or more advanced techniques like Classical Shadows [4] [5]. |

| Eigensolver | A classical numerical routine that solves the generalized eigenvalue problem ( \mathbf{H}C = \mathbf{S}CE ). | Should include regularization (e.g., SVD thresholding) to handle ill-conditioned overlap matrices [26]. |

| 3-(1,3-Dioxan-2-YL)-4'-iodopropiophenone | 3-(1,3-Dioxan-2-YL)-4'-iodopropiophenone, CAS:898785-52-9, MF:C13H15IO3, MW:346.16 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 3-Fluorocyclobutane-1-carbaldehyde | 3-Fluorocyclobutane-1-carbaldehyde, CAS:1780295-33-1, MF:C5H7FO, MW:102.11 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Implementing QSE: Methods and Real-World Applications in Molecular Modeling

Step-by-Step Workflow of a Quantum Subspace Expansion Calculation

Quantum Subspace Expansion (QSE) is a post-processing variational algorithm designed to find accurate ground and excited state energies of molecular systems on quantum computers. It operates by constructing a subspace of wavefunctions from a single, efficiently prepared reference state, often found using the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE). A generalized eigenvalue problem is then solved entirely classically within this subspace to yield refined energy estimates [25] [3].

This protocol details the application of QSE for molecular energy calculations, a critical task in fields like drug discovery and materials science. The method is particularly suited for near-term quantum hardware, as it can mitigate errors and improve accuracy without a significant increase in quantum circuit depth, exchanging this depth for additional measurements [3] [1].

Principle of the Method

The foundational principle of QSE is to expand a computed ground state into a subspace to obtain a better approximation of the true ground state and low-lying excited states.

Consider a molecular Hamiltonian (H) and an approximate ground state (|\Psi0\rangle) obtained from a VQE calculation. The QSE method constructs a subspace of state vectors (|\Psij^k\rangle) formed by applying excitation operators to the ground state wavefunction: [ |\Psi{j}^{k}\rangle = ck^{\dagger}c{j}|\Psi0\rangle ] where (ck^{\dagger}) and (c{j}) are the fermionic creation and annihilation operators, respectively [25].

Within this subspace, one solves the generalized eigenvalue problem: [ H C = S C E ] where:

- (H) is the subspace-projected Hamiltonian with matrix elements (H{jk}^{lm} = \langle \Psi0 | c{j}^\dagger c{l} H c{m}^{\dagger}c{k} | \Psi_0 \rangle).

- (S) is the overlap matrix with matrix elements (S{jk}^{lm} = \langle \Psi0 | c{j}^\dagger c{l} c{m}^{\dagger}c{k} | \Psi_0 \rangle).

- (C) is the matrix of eigenvectors.

- (E) is the vector of eigenvalues, which provides an estimate of the excited state energies and a refined ground state energy [25] [1].

The solution of this generalized eigenvalue equation is performed on a classical computer after the matrix elements of (H) and (S) have been measured on a quantum computer.

Experimental Protocols

This section provides a detailed, step-by-step workflow for performing a QSE calculation, using the methane molecule (CHâ‚„) as a representative example [25].

Step 1: Define the Molecular System and Hamiltonian

The first step involves defining the molecular geometry and obtaining the corresponding electronic structure Hamiltonian.

Procedure:

- Define the molecular geometry, for example, using a Z-matrix.

- Choose a basis set (e.g.,

STO-3G) and run a restricted Hartree-Fock (RHF) calculation using a classical computational chemistry package to obtain the molecular orbitals and electronic integrals. - Freeze core orbitals and apply point group symmetry to reduce the computational cost.

- Generate the fermionic Hamiltonian in second quantization.

- Map the fermionic Hamiltonian to a qubit Hamiltonian using an encoding scheme such as Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev.

- Compress the qubit Hamiltonian by discarding terms with coefficients below a specified threshold (e.g.,

abs_tol=1e-6) to reduce the number of measurements required [25].

Example Parameters for Methane (CHâ‚„):

- Z-matrix: Defined with a C-H bond length of 1.083 Å and H-C-H angles of 109.471°.

- Basis Set:

STO-3G. - Charge:

0. - Frozen Orbitals:

[0, 1, 2, 3, 7, 8]. - Qubit Encoding: Jordan-Wigner.

- Hamiltonian Compression Tolerance:

1e-6. After compression, the Hamiltonian for this methane example contained 34 terms [25].

Step 2: Prepare the Approximate Ground State

Prepare a reference state (|\Psi_0\rangle) that has a non-zero overlap with the true ground state. This is typically done using the VQE algorithm.

Procedure:

- Select an Ansatz: Choose a parameterized quantum circuit (ansatz) that is expressive yet efficient. The Chemically Aware Unitary Coupled Cluster Singlet and Doubles (UCCSD) ansatz is a common choice for molecular systems.

- Optimize Parameters: Use a classical optimizer to variationally minimize the expectation value of the Hamiltonian with respect to the ansatz parameters, (\langle \Psi0(\vec{\theta}) | H | \Psi0(\vec{\theta}) \rangle).

- The final optimized parameters (\vec{\theta}_\text{opt}) define the ground state preparation circuit [25].

Example Parameters for Methane:

- Ansatz:

FermionSpaceAnsatzChemicallyAwareUCCSD. - VQE Backend: A noiseless state-vector simulator (e.g.,

QulacsBackend) can be used for initial testing and validation [25].

- Ansatz:

Step 3: Configure the Quantum Backend and Error Mitigation

Configure the settings for the quantum device or simulator that will execute the circuits.

- Procedure:

- Select a quantum backend (e.g., a Quantinuum emulator, IBM's

ibm_cleveland, or others accessible via cloud services). - Configure error mitigation techniques to improve result quality. For example, the Pauli Measurement Error Reduction by Symmetry Verification (PMSV) technique can be applied [25]. Other advanced error mitigation methods like dynamical decoupling and gate twirling are also used in practice [7] [6].

- Select a quantum backend (e.g., a Quantinuum emulator, IBM's

Step 4: Define and Measure QSE Matrix Elements

This is the most critical quantum step, where the matrix elements for the Hamiltonian ((H)) and overlap ((S)) matrices are measured.

Procedure:

- Define Expansion Operators: Choose a set of (L) operators ({O_i}) to define the subspace. Common choices include:

- Single Fermionic Excitations: (ck^{\dagger}c{j}) for a selected set of spin orbitals (j) and (k) [25].

- Pauli String Operators: Low-weight Pauli operators generated from the system's symmetry or the reference state [1].

- Krylov Vectors: Powers of the Hamiltonian, (H^p), applied to the reference state [3] [1].

- Construct Measurement Circuits: For each matrix element (\mathcal{O}{ij} = \langle \Psi0 | Oi^{\dagger} H Oj | \Psi0 \rangle) and (\mathcal{S}{ij} = \langle \Psi0 | Oi^{\dagger} Oj | \Psi0 \rangle), transform the expression into a linear combination of Pauli observables.

- Measure Expectation Values: Execute the prepared quantum circuits on the backend and measure the expectation values of the required Pauli terms. This can be a significant bottleneck, as the number of measurements scales with (L^2).

- Advanced Measurement Techniques: To overcome the measurement bottleneck, Informationally Complete (IC) measurements, such as Classical Shadows (CS), can be employed. CS uses randomized measurements to reconstruct the state and estimate many observables simultaneously, significantly reducing the measurement overhead [1].

- Define Expansion Operators: Choose a set of (L) operators ({O_i}) to define the subspace. Common choices include:

Example from Large-Scale Implementation:

- A recent 80-qubit QSE experiment used over (3 \times 10^4) measurement basis randomizations per circuit, evaluating (\mathcal{O}(10^{14})) Pauli traces, showcasing the scale required for large systems [1].

Step 5: Classically Solve the Generalized Eigenvalue Problem

The final step is entirely classical and involves solving for the energies of the system within the constructed subspace.