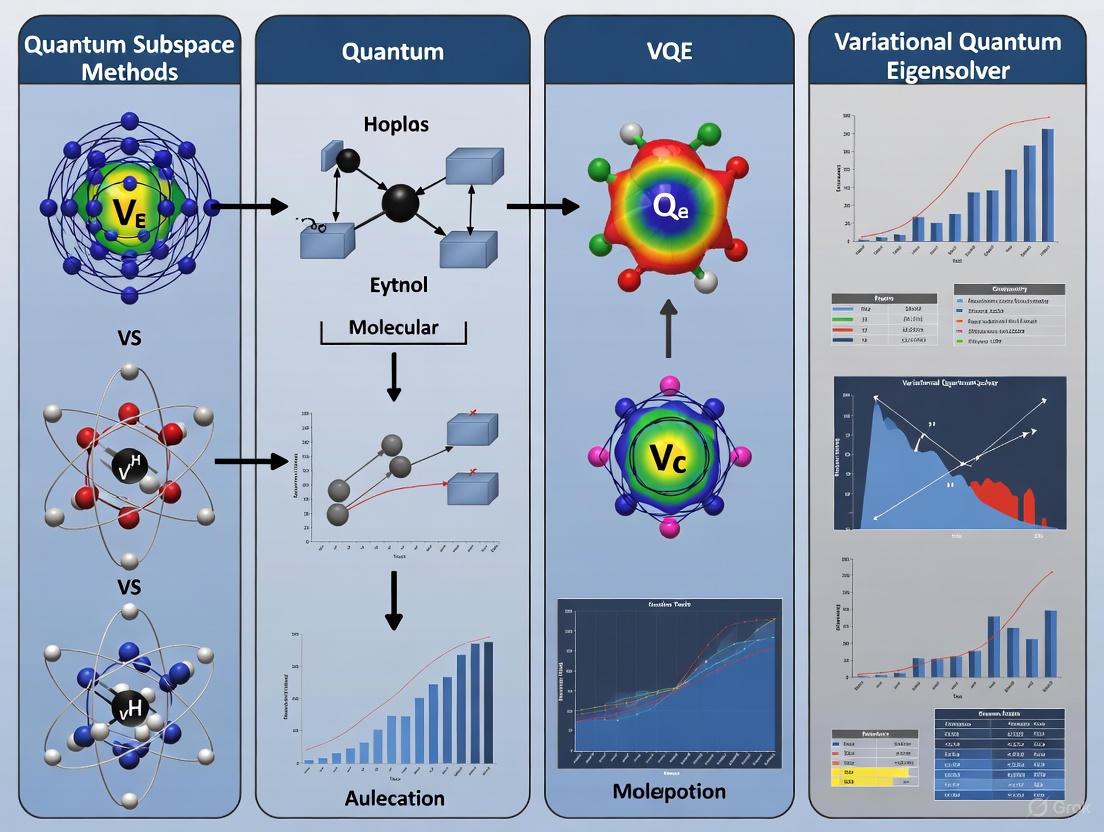

Quantum Subspace Methods vs. VQE: A Comparative Guide for Molecular Simulation in Drug Discovery

This article provides a comparative analysis of Quantum Subspace Methods and the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) for calculating molecular electronic structure, with a focus on applications in drug discovery.

Quantum Subspace Methods vs. VQE: A Comparative Guide for Molecular Simulation in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comparative analysis of Quantum Subspace Methods and the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) for calculating molecular electronic structure, with a focus on applications in drug discovery. Aimed at researchers and pharmaceutical development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of both algorithmic families, details their methodological implementation for ground and excited states, and discusses strategies for error mitigation and circuit optimization on current noisy hardware. The analysis synthesizes recent experimental validations and theoretical advances to offer a clear perspective on the performance, scalability, and near-term practicality of these approaches for simulating biomolecular systems.

Understanding the Quantum Algorithms: From VQE to Subspace Principles

The pursuit of solving the electronic structure problem—determining the spatial distribution and energy of electrons in a molecule—is a central challenge in quantum chemistry. This problem is pivotal for predicting chemical properties, reaction mechanisms, and material behaviors, but its solution requires approximating the many-electron Schrödinger equation, a task whose computational cost scales exponentially with system size on classical computers. In recent years, quantum computing has emerged as a potential pathfinder, offering novel algorithms to navigate this exponentially complex landscape. Among the most prominent are the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE), a well-established hybrid quantum-classical method, and the more specialized Quantum Subspace Methods, including the Contextual Subspace VQE (CS-VQE). This guide provides an objective comparison of these approaches, detailing their performance, experimental protocols, and resource requirements to inform researchers in chemistry and drug development.

Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE)

VQE is a hybrid quantum-classical algorithm designed to find the ground state energy of a quantum system, such as a molecule. Its operation is based on the variational principle: a parameterized quantum circuit (ansatz) prepares a trial wavefunction on a quantum computer, whose energy expectation value is measured. A classical optimizer then adjusts the parameters to minimize this energy [1] [2] [3].

Key Components:

- Objective: Find the minimum eigenvalue (ground state energy) of a Hamiltonian

H. - Cost Function: ( C(\theta) = \langle \Psi(\theta) | H | \Psi(\theta) \rangle ), where ( |\Psi(\theta)\rangle ) is the trial state [4].

- Process: Iterative hybrid loop between quantum state preparation/measurement and classical parameter optimization [3].

Contextual Subspace VQE (CS-VQE)

CS-VQE is an advanced variant that reduces quantum resource demands. Instead of solving the entire problem on the quantum computer, it classically solves a large part of the system and uses a quantum processor to calculate a correction within a carefully chosen, smaller "contextual subspace" of the full Hilbert space. This subspace contains the most strongly correlated electrons and is identified using classical methods like MP2 natural orbitals [5].

Key Components:

- Objective: Achieve accurate ground state energies with reduced quantum resource requirements.

- Core Innovation: Hybrid quantum-classical partitioning of the problem; a large, weakly correlated part is solved classically, while a smaller, highly correlated contextual subspace is solved on the quantum device [5].

- Process: The total energy is expressed as ( E{total} = E{classical} + E{quantum} ), where ( E{quantum} ) is the energy correction from the VQE calculation on the subspace [5].

Performance Comparison: VQE vs. CS-VQE

The table below summarizes key performance characteristics and experimental results for VQE and CS-VQE based on recent studies and hardware demonstrations.

Table 1: Performance and Resource Comparison of VQE and CS-VQE

| Feature | Standard VQE | Contextual Subspace VQE (CS-VQE) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Compute molecular ground state energy [2] | Accurate energy correction with reduced quantum resources [5] |

| Typical Accuracy (vs. FCI) | Can achieve chemical accuracy for small molecules (e.g., Hâ‚‚, LiH) [2] | Good agreement with FCI; outperforms single-reference methods like CCSD in bond-breaking [5] |

| Key Demonstrations | Hâ‚‚, LiH, Hâ‚‚O, H₃âº, OHâ», HF, BH₃ [2] [4] | Dissociation curve of Nâ‚‚ [5] |

| Quantum Resource Reduction | N/A (Solves full problem on quantum device) | Competitive with multiconfigurational approaches at a saving of quantum resource [5] |

| Classical Component Role | Optimization of quantum circuit parameters [1] | Selection of contextual subspace & computation of ( E_{classical} ) [5] |

| Error Mitigation Integration | Commonly used (Zero-Noise Extrapolation, etc.) [6] | Dynamical Decoupling, Measurement-Error Mitigation, Zero-Noise Extrapolation [5] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Detailed Workflow for a Standard VQE Experiment

The following protocol is typical for simulating small molecules like H₂ or BH₃ [2] [4]:

Problem Definition:

- Molecular Geometry: Define the atomic coordinates and bond lengths of the target molecule (e.g., Hâ‚‚ bond length of 1.623 Ã…) [3].

- Basis Set: Select a basis set, such as the minimal STO-3G [4].

- Hamiltonian Generation: Using the Born-Oppenheimer approximation, the electronic Hamiltonian is formulated in the second quantized form and then mapped to a qubit operator using a transformation like Jordan-Wigner or Parity mapping [2] [4].

Ansatz Preparation:

- Initial State: Prepare the Hartree-Fock state as the initial reference state [3].

- Ansatz Circuit: Choose a parameterized quantum circuit. The Unitary Coupled Cluster with Singles and Doubles (UCCSD) ansatz is common for chemical accuracy, though hardware-efficient ansatzes like

EfficientSU2are also used [3] [4].

Execution & Optimization:

- Estimator: Use a quantum estimator (often with simulators or real hardware) to compute the expectation value of the Hamiltonian [3].

- Classical Optimizer: Employ a classical optimization algorithm (e.g., SLSQP, SPSA, BFGS) to minimize the energy by updating the ansatz parameters [1] [4]. This hybrid loop runs until convergence.

Validation:

- The final VQE result is validated against classically computed exact energies from methods like the NumPyMinimumEigensolver or Full Configuration Interaction (FCI) [3].

Detailed Workflow for a CS-VQE Experiment

The protocol for CS-VQE, as demonstrated for the Nâ‚‚ dissociation curve, involves additional classical pre-processing [5]:

Classical Pre-processing and Subspace Selection:

- Initial Classical Calculation: Perform a preliminary classical computation (e.g., MP2) to obtain natural orbitals.

- Active Space Identification: Analyze the orbital occupation numbers from the natural orbitals. Orbitals with occupations deviating significantly from 0 or 2 are considered highly correlated and form the candidate "contextual subspace."

- Hybrid Partitioning: The full Hamiltonian is partitioned. A large part of the system is solved classically (( E_{classical} )), leaving a reduced Hamiltonian for the contextual subspace to be solved by VQE.

Quantum Subspace Calculation:

- Reduced Hamiltonian: The contextual subspace Hamiltonian is mapped to a qubit operator, requiring fewer qubits than the full problem.

- Hardware-Aware Ansatz: An ansatz is constructed, potentially with hardware topology in mind (e.g., using a modified qubit-ADAPT-VQE algorithm) to minimize transpilation costs [5].

- VQE Execution: Run the VQE algorithm on the reduced Hamiltonian.

Energy Synthesis and Error Mitigation:

- The total energy is computed as ( E{total} = E{classical} + E_{quantum} ).

- Advanced error mitigation strategies are critical for hardware runs, including Dynamical Decoupling, Measurement-Error Mitigation, and Zero-Noise Extrapolation (ZNE) [5].

Workflow Visualization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

This section details key computational "reagents" and tools essential for conducting VQE and CS-VQE experiments, as cited in the literature.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Quantum Chemistry Experiments

| Tool / Reagent | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| STO-3G Basis Set | A minimal Gaussian basis set used to represent molecular orbitals, reducing computational cost [4]. | Prototyping algorithms for small molecules like Hâ‚‚ and Nâ‚‚ [4]. |

| UCCSD Ansatz | A chemistry-inspired parameterized quantum circuit that approximates the electronic wavefunction by including single and double excitations [3]. | Achieving chemically accurate results for small molecules in VQE [3] [4]. |

| Parity Mapper | A fermion-to-qubit mapping technique that converts the electronic Hamiltonian into a form executable on a quantum processor [3]. | Mapping molecular Hamiltonians to qubit operators in VQE simulations [3]. |

| SLSQP Optimizer | A sequential least squares programming algorithm, a gradient-based classical optimizer used in the VQE loop [3]. | Efficiently converging VQE parameters to the minimum energy [3]. |

| Zero-Noise Extrapolation (ZNE) | An error mitigation technique that intentionally increases circuit noise to extrapolate back to a zero-noise result [5] [6]. | Improving the accuracy of energy expectations on noisy quantum hardware [5]. |

| PySCF | A classical computational chemistry software used to compute molecular integrals and generate electronic structure problems [3]. | Providing the initial Hamiltonian and reference energies for VQE experiments [3]. |

| QM9 Dataset | A benchmark dataset of ~134k small organic molecules with computed quantum-chemical properties [7]. | Training and benchmarking machine learning models for property prediction [7]. |

| (S)-Benzyl 2-amino-3-hydroxypropanoate | (S)-Benzyl 2-amino-3-hydroxypropanoate, CAS:1738-72-3, MF:C10H13NO3, MW:195.21 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Desfuroyl Ceftiofur S-Acetamide | Desfuroyl Ceftiofur S-Acetamide, CAS:120882-25-9, MF:C16H18N6O6S3, MW:486.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

For researchers tackling the electronic structure problem, the choice between standard VQE and CS-VQE is a trade-off between algorithmic generality and resource efficiency. Standard VQE provides a flexible, general framework that has been successfully demonstrated on various small molecules, serving as a foundational method for the NISQ era. In contrast, CS-VQE represents a strategic evolution, explicitly designed to extend the reach of quantum computations by leveraging classical resources to handle a significant portion of the problem. This allows it to tackle more challenging chemical phenomena, such as bond dissociation in Nâ‚‚, with higher accuracy than many classical single-reference methods and with fewer quantum resources than a full VQE calculation. The decision pathway is clear: use standard VQE for foundational studies on smaller systems, and adopt CS-VQE when pushing the boundaries of problem size and complexity, particularly where strong electron correlation is paramount.

In the fields of drug discovery and materials science, accurately predicting the quantum mechanical properties of molecules is a fundamental challenge. Classical computational methods, such as Density Functional Theory (DFT) and Coupled Cluster, often face a trade-off between scalability and accuracy, particularly for systems with strong electron correlation [8]. The Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) emerged as a pioneering hybrid quantum-classical algorithm designed to overcome these limitations. VQE leverages quantum computers to naturally represent quantum states, using a parameterized quantum circuit as a trial wavefunction, while employing classical optimizers to find the ground state energy [3] [8].

This guide objectively compares VQE's performance against alternative methods, particularly quantum subspace approaches, focusing on experimental data and practical implementations for molecular systems. Quantum subspace methods, such as those utilizing the ADAPT-VQE convergence path, offer a different strategy by constructing effective Hamiltonians in a subspace to find both ground and excited states [9]. We provide a detailed comparison of their protocols, performance, and resource requirements to inform researchers and development professionals in selecting the appropriate tool for their specific challenges.

Core Principles of the VQE Algorithm

The VQE algorithm is built on the variational principle of quantum mechanics. It finds the ground state energy of a system by minimizing the expectation value of a Hamiltonian ( H ) with respect to a parameterized trial wavefunction ( |\Psi(\theta)\rangle ) [3]. The objective is expressed as: [ E = \min_{\theta} \langle \Psi(\theta) | H | \Psi(\theta) \rangle ] where ( E ) is the ground state energy and ( \theta ) represents the variational parameters [3].

The VQE Workflow

The algorithm follows a hybrid quantum-classical feedback loop, visualized in the diagram below.

Figure 1: The hybrid quantum-classical feedback loop of the VQE algorithm. The quantum computer prepares trial states and measures the energy, while the classical computer updates the parameters to minimize the energy [3] [8].

Key Mathematical Components

The Hamiltonian: For quantum chemistry, the electronic structure Hamiltonian in the second quantization formulation is: [ H = \sum{pq} h{pq} ap^\dagger aq + \sum{pqrs} h{pqrs} ap^\dagger aq^\dagger ar as ] where ( h{pq} ) and ( h{pqrs} ) are one- and two-electron integrals, and ( ap^\dagger ), ( aq ) are fermionic creation and annihilation operators [3]. This Hamiltonian is then mapped to a qubit operator using transformations such as Jordan-Wigner or Parity mapping [3] [4].

The Ansatz: The parameterized quantum circuit ( U(\theta) ) generates the trial wavefunction from an initial state: ( |\psi(\theta)\rangle = U(\theta) |\psi_0\rangle ). Common choices include:

Performance Comparison: VQE vs. Quantum Subspace Methods

Direct performance comparisons between VQE and quantum subspace methods are emerging in research literature. The table below summarizes key findings from experimental studies.

Table 1: Performance comparison of VQE and Quantum Subspace Methods for molecular simulation.

| Metric | VQE (UCCSD Ansatz) | Quantum Subspace (from ADAPT-VQE path) | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Objective | Ground state energy calculation [8] | Ground and low-lying excited states [9] | Applied to Hâ‚‚ and Hâ‚„ dissociation [9] |

| Algorithmic Approach | Variational minimization on a parameterized quantum state [3] | Diagonalization of an effective Hamiltonian built from quantum states generated during VQE convergence [9] | Subspace methods use VQE-generated states as a basis [9] |

| Key Advantage | Direct, physically motivated optimization of ground state [8] | Access to excited states from a single set of calculations [9] | Provides a more complete energy spectrum picture [9] |

| Computational Overhead | Multiple measurements for energy estimation; many optimization iterations [3] [4] | Additional classical diagonalization step, but utilizes existing quantum states [9] | The overhead of diagonalization is typically small compared to quantum resource costs [9] |

Experimental Protocols and Benchmarking Data

Benchmarking hybrid quantum algorithms requires standardized use cases and careful measurement of both accuracy and computational resources.

Standardized Use Cases for Benchmarking

Researchers often employ a suite of standard problems to ensure consistent comparisons across different algorithms and hardware platforms [4].

- The Hâ‚‚ Molecule: A foundational benchmark in quantum chemistry. The protocol involves:

- Define Geometry: Set the bond length (e.g., 1.623 Ã… for Hâ‚‚) [3].

- Generate Hamiltonian: Use quantum chemistry packages (like PySCF) with a specified basis set (e.g., STO-3G) to generate the electronic Hamiltonian within the Born-Oppenheimer approximation [3] [4].

- Qubit Mapping: Transform the fermionic Hamiltonian to a qubit Hamiltonian using a mapping technique like Jordan-Wigner or Parity [3] [4].

- MaxCut and Traveling Salesman Problem (TSP): These combinatorial optimization problems are translated into Ising-like Hamiltonians and solved using variants like the Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm (QAOA) [4].

Performance on HPC Systems

A 2025 study compared the performance of VQE simulations across different High-Performance Computing (HPC) systems and software simulators [4]. The study highlighted that variational algorithms are often limited by long runtimes relative to their memory footprint, which can restrict their parallel scalability on HPC systems. A key finding was that this limitation could be partially mitigated by using techniques like job arrays [4].

The study also successfully used a parser tool to port problem definitions (Hamiltonian and ansatz) consistently across different simulators, ensuring fair and meaningful comparisons of performance and results [4].

The Role of Classical Simulations

Classical simulation of quantum computers plays a vital role in developing and validating quantum algorithms like VQE. Pushing the boundaries of these simulations is a research area in itself. A recent milestone was set by the JUPITER supercomputer, which simulated a universal quantum computer with 50 qubits, breaking the previous record of 48 qubits [10]. This was enabled by innovations in memory technology and data compression, requiring about 2 petabytes of memory [10]. Such simulations provide essential testbeds for exploring new algorithmic approaches before they can be run on actual quantum hardware.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Implementing VQE and related algorithms requires a suite of software tools and theoretical components. The following table details these essential "research reagents" and their functions.

Table 2: Key tools and components for VQE and quantum subspace research.

| Tool / Component | Category | Function | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Basis Set | Chemistry Input | A set of functions used to represent the molecular orbitals of the system [3]. | STO-3G [3] |

| Fermion-to-Qubit Mapper | Software Component | Transforms the electronic Hamiltonian from fermionic operators to Pauli spin operators usable on a quantum computer [3] [4]. | Jordan-Wigner, Parity Mapper [3] [4] |

| Ansatz Circuit | Algorithm Core | A parameterized quantum circuit that generates the trial wavefunction for the variational search [3]. | UCCSD, EfficientSU2 [3] |

| Classical Optimizer | Software Component | A classical algorithm that adjusts the parameters of the ansatz to minimize the energy expectation value [3] [4]. | SLSQP, COBYLA, BFGS [3] [4] |

| Quantum Subspace Diagonalization | Algorithm Core | A technique to extract ground and excited states by building and diagonalizing an effective Hamiltonian in a subspace spanned by quantum states [9]. | Using states from the ADAPT-VQE convergence path [9] |

| N-Butyryl-N'-cinnamyl-piperazine | N-Butyryl-N'-cinnamyl-piperazine, CAS:17719-89-0, MF:C17H24N2O, MW:272.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| 4-(3,4-Difluorophenyl)-4-oxobutanoic acid | 4-(3,4-Difluorophenyl)-4-oxobutanoic acid|CAS 84313-94-0 | CAS 84313-94-0. This high-purity 4-(3,4-Difluorophenyl)-4-oxobutanoic acid is a key synthetic intermediate for research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

The comparative analysis indicates that VQE and quantum subspace methods are not mutually exclusive but can be complementary. VQE provides a robust, direct route to the ground state, making it a versatile tool for today's NISQ devices with applications in drug discovery, materials science, and catalyst design [8]. Quantum subspace methods, particularly those built upon VQE's convergence path, efficiently extract more spectral information from the same quantum computations, offering a pathway to study excited states and complex quantum dynamics [9].

The choice between them depends on the research goal: VQE for a focused, ground-state investigation, and subspace methods for a comprehensive energy spectrum analysis. As quantum hardware continues to advance, the integration of these hybrid quantum-classical strategies is poised to become a standard methodology, unlocking new possibilities in molecular simulation and beyond.

The accurate calculation of molecular excited states is a cornerstone for advancing research in photochemistry, material design, and drug development. On noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices, the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) has emerged as a primary algorithm for ground-state energy calculations. However, its extension to excited states presents unique challenges and opportunities. This guide focuses on two prominent algorithms for this task: the Subspace Search Variational Quantum Eigensolver (SSVQE) and the Variational Quantum Deflation (VQD). Framed within the broader context of quantum subspace methods, these algorithms represent a shift from the single-state optimization of VQE towards techniques that capture a broader spectrum of the molecular energy landscape, a capability critical for understanding photophysical properties and reaction dynamics.

Algorithmic Foundations: SSVQE vs. VQD

Core Principles and Theoretical Frameworks

Variational Quantum Deflation (VQD) is an iterative algorithm designed to find excited states by building upon previously calculated states. It computes the k-th excited state by incorporating a cost function that includes penalty terms to ensure orthogonality to all lower-lying states (i-1 to 0) [11] [12]. For the first excited state, the cost function is typically: ( C1(\theta) = \langle \psi(\theta) | H | \psi(\theta) \rangle + \sum{i} \betai |\langle \psi(\theta) | \psii \rangle|^2 ) where ( \beta_i ) are hyperparameters that must be sufficiently large to enforce orthogonality, roughly greater than the energy difference between the current and the i-th state [12]. A significant challenge with VQD is the pre-selection of these ( \beta ) hyperparameters, as overly large values can lead to convergence to undesired higher-energy states [12].

Subspace Search Variational Quantum Eigensolver (SSVQE) takes a different, non-iterative approach. It aims to find a unitary transformation that maps a set of orthogonal input states (e.g., computational basis states) to a set of low-energy eigenstates [13]. A single parameterized quantum circuit is applied to all input states, and the goal is to minimize a weighted sum of their energies: ( L(\theta) = \sumk wk \langle \psik(\theta) | H | \psik(\theta) \rangle ) where ( wk ) are weights, often chosen such that ( w0 > w1 > ... > wk ). The unitarity of the transformation naturally preserves the orthogonality of the output states, which is a key advantage [14].

Comparative Analysis: Key Characteristics

Table 1: Core Algorithmic Characteristics of SSVQE and VQD.

| Feature | Subspace Search VQE (SSVQE) | Variational Quantum Deflation (VQD) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Philosophy | Simultaneous subspace diagonalization | Sequential, iterative state finding |

| Orthogonality Enforcement | Inherent from unitary transformation [14] | Via penalty terms in cost function [11] [12] |

| Hyperparameter Tuning | Minimal impact from weight choices [11] | Critical; requires careful selection of ( \beta ) penalty parameters [12] |

| Circuit Utilization | Single circuit applied to multiple input states | One circuit optimization per target state |

| Classical Optimization | Single optimization for multiple states | Multiple sequential optimizations |

| Resource Scaling | More efficient for obtaining several low-lying states [13] | Becomes more expensive for higher excited states [11] |

Performance and Experimental Comparison

Experimental studies on model systems and real molecules provide crucial insights into the practical performance of these algorithms.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Comparison of SSVQE and VQD.

| Study / System | Algorithm | Reported Performance | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| GaAs Crystal (10-qubit) [11] | VQD | Accuracy for higher states improved by an order of magnitude with hyperparameter tuning. | Hyperparameter tuning is especially critical for VQD to achieve reliable outcomes for higher energy states [11]. |

| GaAs Crystal (10-qubit) [11] | SSVQE | Tuning hyperparameters had minimal impact on performance. | SSVQE offers promising results with less sensitivity to hyperparameter choices [11]. |

| Ethylene & Phenol Blue [12] | VQD | Energy errors up to 2 kcal molâ»Â¹ on real hardware (ibm_kawasaki). | Demonstrates feasibility on NISQ devices, but highlights challenges with cost function errors [12]. |

| Nâ‚‚ Dissociation [5] | Contextual Subspace VQE | Good agreement with FCI, outperforming single-reference methods like CCSD. | Highlights a subspace method competitive with multiconfigurational approaches but with quantum resource savings [5]. |

| Hâ‚‚, LiH, BeHâ‚‚ [14] | SSVQE (with SPA ansatz) | Achieved CCSD-level chemical accuracy for ground and excited states. | High-depth, symmetry-preserving ansatze are crucial for accuracy in both ground and excited states [14]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and provide a clear framework for benchmarking, the following protocols detail the methodologies from key cited experiments.

Protocol 1: Electronic Structure of GaAs Crystal [11] This study provides a direct comparison of VQD and SSVQE for a solid-state system.

- System: Gallium Arsenide (GaAs) crystal with a zinc-blende structure.

- Hamiltonian: A 10-qubit tight-binding Hamiltonian ((sp^3s^*) model) transformed via a Jordan-Wigner-like mapping [11].

- Software/Hardware: Simulations performed using a quantum computer statevector simulator.

- Variational Ansatz: Specific quantum circuit architectures were analyzed, with a focus on their impact on performance.

- Optimization: Different classical optimizers were tested to minimize the algorithm-specific cost functions.

- Key Metric: The accuracy of the calculated energy bands compared to classical tight-binding results, with chemical accuracy defined as an error less than 0.04 eV [11].

Protocol 2: Excited States at Conical Intersections [12] This work underscores the importance of excited states for photochemistry and introduces an alternative method.

- Systems: Ethylene and phenol blue molecules, focusing on Frank-Condon and Conical Intersection geometries.

- Methodology: Complete Active Space Self-Consistent Field (CASSCF) calculations implemented on a quantum device.

- Algorithm: A comparison of VQD and the VQE under Automatically-Adjusted Constraints (VQE/AC).

- Ansatz: Use of a chemistry-inspired, spin-restricted ansatz to prevent spin contamination and reduce circuit depth [12].

- Error Mitigation: Calculations were performed on the

ibm_kawasakidevice, incorporating standard NISQ-era error mitigation techniques. - Key Metric: Deviation of calculated excited state energies from classically computed CASSCF benchmarks.

Workflow and Algorithmic Pathways

The fundamental workflows for SSVQE and VQD, from problem definition to the final result, are visualized below.

The Researcher's Toolkit

Successful implementation of these algorithms requires a suite of theoretical and computational tools. The following table details essential "research reagents" for conducting excited-state calculations on quantum hardware.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Excited-State VQE Calculations.

| Tool Category | Specific Example | Function & Importance |

|---|---|---|

| Fermion-to-Qubit Mapping | Jordan-Wigner Transformation [11] [13] | Maps electronic Hamiltonians to qubit operators, preserving anti-commutation relations. Essential for problem encoding. |

| Variational Ansatz | Symmetry-Preserving Ansatz (SPA) [14] | A hardware-efficient ansatz that conserves physical quantities like particle number, improving accuracy and reducing resource needs. |

| Variational Ansatz | Unitary Coupled Cluster (UCCSD) [14] | A chemically inspired ansatz that is highly accurate but can require deep circuits, making it challenging on NISQ devices. |

| Classical Optimizer | QN-SPSA+PSR [1] | A combinatorial optimizer combining the efficiency of quantum natural SPSA with the precise gradient from the parameter-shift rule. |

| Error Mitigation | Zero-Noise Extrapolation [5] | A technique to infer the noiseless value of an observable by measuring at different noise levels. |

| Resource Reduction | Contextual Subspace Method [5] | Identifies and solves only the most correlated part of the problem on the quantum computer, drastically reducing qubit requirements. |

| Initial State | Hartree-Fock State | The typical starting point for VQE calculations, often used as one of the input states for SSVQE. |

| 2-(4-Fluorophenyl)sulfanylbenzoic acid | 2-(4-Fluorophenyl)sulfanylbenzoic acid, CAS:13420-72-9, MF:C13H9FO2S, MW:248.27 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 6-Bromo-2-hydrazino-1,3-benzothiazole | 6-Bromo-2-hydrazino-1,3-benzothiazole, CAS:37390-63-9, MF:C7H6BrN3S, MW:244.11 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The journey beyond ground-state VQE has led to the development of powerful algorithms like VQD and SSVQE, each with distinct strengths. VQD offers a direct, sequential approach to finding excited states but requires careful management of hyperparameters to ensure accuracy and avoid convergence issues. SSVQE, as a quantum subspace method, provides a more holistic and often more efficient path to obtaining several low-lying states simultaneously, with inherent orthogonality and less sensitivity to its hyperparameters.

The broader trend in the field leans towards quantum subspace methods, which include SSVQE and other approaches like the Contextual Subspace VQE [5] and Qumode Subspace VQE [13]. These methods align well with the constraints of NISQ hardware by focusing quantum resources on the most computationally demanding sub-problems. As quantum hardware continues to evolve, these algorithmic advances—combined with robust error mitigation and resource-efficient encodings—are paving a credible path toward quantum utility in simulating the excited-state properties of molecules and materials, with profound implications for drug discovery and advanced materials design.

Quantum subspace methods (QSMs) represent a fundamental shift in strategy for simulating molecular systems on quantum computers. While the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) has dominated early research in quantum computational chemistry, its limitations in treating strong correlation and its sensitivity to noise have prompted the development of alternative approaches [15]. QSMs address these challenges by projecting the complex electronic structure problem onto a smaller, carefully constructed subspace, where the Schrödinger equation is solved as a manageable eigenvalue problem using classical resources [16].

This guide provides an objective comparison between quantum subspace methods and VQE-based approaches, focusing on their performance, resource requirements, and applicability to molecular systems. We present experimental data from recent studies, detailed methodologies, and practical resources to help researchers select the most appropriate algorithm for their specific computational chemistry challenges.

Theoretical Framework and Methodological Comparison

Fundamental Principles of Quantum Subspace Diagonalization

Quantum subspace methods operate on a simple yet powerful principle: instead of searching for ground or excited states by optimizing parameterized quantum circuits, they construct an effective Hamiltonian within a small subspace of the full Hilbert space. The time-independent Schrödinger equation is projected onto this subspace, transforming it into a generalized eigenvalue problem that can be solved efficiently on a classical computer [16]. Mathematically, this involves constructing overlap (B) and Hamiltonian (A) matrices with elements:

[ A{a,b} = \langle v(ta)|\hat{H}|v(tb)\rangle \quad \text{and} \quad B{a,b} = \langle v(ta)|v(tb)\rangle ]

where (|v(t)\rangle = e^{-i\hat{H}t}|\psi0\rangle) are basis states generated by time evolution from an initial reference state (|\psi0\rangle) [17]. Diagonalizing the projected Hamiltonian within this subspace yields approximations to the ground and excited states of the full system.

Comparative Analysis of Algorithmic Strategies

Table 1: Comparison of Quantum Subspace Method Variants

| Method | Subspace Construction | Key Innovation | Measurement Requirements | Hardware Compatibility | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contextual Subspace VQE [5] | MP2 natural orbitals | Reduces quantum resource via hybrid quantum-classical partitioning | Reduced via Qubit-Wise Commuting decomposition | Enhanced via hardware-aware ansatz and error mitigation | |

| Quantum Krylov Diagonalization [17] | Time-evolved states (e^{-i\hat{H}t} | \psi_0\rangle) | Leverages time-reversal symmetry to avoid controlled operations | Real-valued overlaps reduce measurement complexity | Compatible with shallow quantum architectures |

| Q-SENSE [18] | Seniority symmetry sectors | Guarantees orthogonality through distinct symmetry sectors | Reduced due to symmetry-induced sparsity | Lower circuit depth in exchange for more matrix elements | |

| Quantum Subspace Expansion [15] | Excitations from trial state | Diagonalizes Hamiltonian in small subspace around VQE solution | Requires measuring all matrix elements in subspace | Mitigates decoherence impact on excited states |

Experimental Performance and Benchmarking

Molecular Nitrogen Dissociation: A Case Study in Strong Correlation

The dissociation curve of molecular nitrogen (Nâ‚‚) presents a particularly challenging benchmark due to the dominance of static correlation in the dissociation limit, where single-reference methods like Restricted Open-Shell Hartree-Fock (ROHF) break down [5]. Recent experimental implementation of the Contextual Subspace VQE (CS-VQE) on superconducting hardware has demonstrated remarkable performance for this system.

In this study, researchers calculated the potential energy curve of Nâ‚‚ in the STO-3G basis across ten bond lengths between 0.8Ã… and 2.0Ã…. The methodology incorporated an error mitigation strategy combining Dynamical Decoupling, Measurement-Error Mitigation, and Zero-Noise Extrapolation. Circuit parallelization provided passive noise-averaging and improved effective shot yield [5].

Table 2: Performance Comparison for Nâ‚‚ Dissociation (STO-3G Basis)

| Method | Accuracy near Equilibrium | Accuracy at Dissociation | Qubit Requirements | Notable Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CS-VQE [5] | Good agreement with FCI | Good agreement with FCI | Reduced via contextual subspace | Minimal basis set in current implementation |

| CCSD [5] | High accuracy | Poor description of bond-breaking | N/A (classical) | Fails for strong correlation |

| CCSD(T) [5] | Very high accuracy | Moderate improvement over CCSD | N/A (classical) | Still inadequate for exact dissociation |

| CASSCF [5] | Moderate accuracy | High accuracy with sufficient active space | N/A (classical) | Exponential scaling with active space size |

| UHF [5] | Moderate accuracy | Qualitatively correct but spin-contaminated | N/A (classical) | Incorrect spatial/spin symmetry |

The experimental results demonstrated that CS-VQE retained good agreement with Full Configuration Interaction (FCI) energies across the entire dissociation curve, outperforming all benchmarked single-reference wavefunction techniques and being competitive with multiconfigurational approaches like CASSCF, but at a significant saving of quantum resources [5]. This resource efficiency means larger active spaces can be treated for a fixed qubit allowance, potentially enabling more accurate simulations on near-term devices.

Resource Efficiency and Measurement Overhead

Different subspace methods offer varying trade-offs between circuit depth, measurement overhead, and classical computation requirements. The Quantum SENiority-based Subspace Expansion (Q-SENSE), for instance, explicitly exchanges lower circuit complexity for the need to compute additional Hamiltonian matrix elements [18]. This trade-off is particularly beneficial for near-term devices where circuit depth is a primary limitation.

The Krylov Time Reversal (KTR) protocol exemplifies another resource reduction strategy by leveraging time-reversal symmetry in Hamiltonian evolution to recover real-valued Krylov matrix elements. This significantly reduces circuit depth and enhances compatibility with shallow quantum architectures by avoiding controlled operations that are challenging to implement on current hardware [17].

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Contextual Subspace VQE Workflow

The implementation of CS-VQE for molecular nitrogen followed a detailed protocol [5]:

Active Space Selection: Contextual subspaces were selected using MP2 natural orbitals, similar to the approach used for CASCI/CASSCF active spaces for fair comparison. Orbitals with occupation numbers close to zero or two were considered inactive.

Ansatz Construction: A modified adaptive ansatz construction algorithm (qubit-ADAPT-VQE) was employed with hardware awareness incorporated through a penalizing contribution in the excitation pool scoring function, minimizing transpilation cost for the target qubit topology.

Error Mitigation: A comprehensive error suppression strategy was deployed, comprising:

- Dynamical Decoupling to suppress environmental interactions

- Measurement-Error Mitigation to correct readout errors

- Zero-Noise Extrapolation to estimate noise-free energies

Measurement Reduction: Qubit-Wise Commuting (QWC) decomposition of the reduced Hamiltonians was performed to minimize the number of required measurements.

Circuit Parallelization: Circuits were parallelized to provide passive noise-averaging and improve the effective shot yield, reducing measurement overhead.

CS-VQE Workflow for Molecular Simulation

Quantum Krylov Diagonalization with Time Reversal Symmetry

The KTR protocol implements a specialized form of quantum subspace diagonalization suitable for Hamiltonians with time-reversal symmetry [17]:

Initial State Preparation: Prepare a reference state (|v_0\rangle) with non-zero overlap with the target ground state.

Time-Evolved Basis Construction: Generate basis states (|v(t)\rangle = e^{-i\hat{H}t}|v0\rangle) for a set of time displacements (ta, t_b \in \mathcal{I}).

Real-Valued Overlap Recovery: For Hamiltonians satisfying ({T,\hat{H}}=0) with (T) a Hermitian involutory operator, exploit the time-reversal symmetry to recover real-valued matrix elements (\langle v(ta)|\hat{H}|v(tb)\rangle) and (\langle v(ta)|v(tb)\rangle) without controlled operations.

Matrix Construction and Diagonalization: Construct the (A) and (B) matrices as described in Section 2.1 and solve the generalized eigenvalue problem (A\boldsymbol{x}=\lambda B\boldsymbol{x}) classically to obtain spectral approximations.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Experimental Components for Quantum Subspace Simulations

| Component | Function | Implementation Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Error Mitigation Suite [5] [19] | Suppress hardware noise to improve accuracy | Dynamical Decoupling, Measurement-Error Mitigation, Zero-Noise Extrapolation, Twirled Readout Error Extinction (T-REx) |

| Hardware-Aware Compilation [5] | Minimize circuit depth for target qubit topology | Modified ADAPT-VQE with hardware penalty in excitation pool scoring, Qubit topology-aware transpilation |

| Symmetry Exploitation [18] [17] | Reduce measurement overhead and guarantee orthogonality | Seniority symmetry sectors (Q-SENSE), Time-reversal symmetry (KTR) |

| Measurement Reduction [5] | Decrease number of circuit executions | Qubit-Wise Commuting (QWC) decomposition, Classical shadows techniques |

| Subspace Selection Heuristics [5] [16] | Identify most relevant subspace for accurate results | MP2 natural orbitals, Adaptive selection based on correlation metrics, Krylov time evolution |

| 1,2-benzisothiazol-3(2H)-one 1-oxide | 1,2-benzisothiazol-3(2H)-one 1-oxide, CAS:14599-38-3, MF:C7H5NO2S, MW:167.19 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 5-Chloro-2-(2-hydroxyethoxy)pyridin-3-ol | 5-Chloro-2-(2-hydroxyethoxy)pyridin-3-ol, CAS:1305324-75-7, MF:C7H8ClNO3, MW:189.59 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Essential Components of Quantum Subspace Toolkit

Quantum subspace methods offer a compelling alternative to VQE for molecular electronic structure calculations, particularly for systems with strong correlation where single-reference methods fail. The experimental evidence from molecular nitrogen dissociation demonstrates that approaches like CS-VQE can achieve accuracy competitive with multiconfigurational classical methods while reducing quantum resource requirements [5].

For researchers and drug development professionals, the choice between subspace methods and VQE depends on specific application requirements. VQE may remain suitable for weakly correlated systems near equilibrium, where established ansätze like UCCSD perform adequately. However, for bond dissociation, transition state mapping, and other strongly correlated scenarios, quantum subspace methods provide superior performance with more favorable resource scaling.

As quantum hardware continues to evolve, the reduced circuit depth requirements of methods like KTR [17] and Q-SENSE [18] position subspace diagonalization as a promising pathway toward practical quantum advantage in chemical simulation. The systematic integration of error mitigation, measurement reduction, and hardware awareness creates a robust framework for extracting chemically meaningful results from current noisy quantum devices.

In the pursuit of quantum solutions for molecular systems, two distinct algorithmic strategies have emerged: parameter optimization and subspace representation. The Parameter Optimization approach, exemplified by the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE), relies on tuning quantum circuit parameters to minimize the expectation value of a molecular Hamiltonian [4]. In contrast, Subspace Representation methods project the complex electronic structure problem into a smaller, classically tractable subspace where the Schrödinger equation is solved more efficiently [20] [5]. This comparison guide examines their fundamental operational principles, performance characteristics, and suitability for molecular research applications, particularly in pharmaceutical development.

Conceptual Frameworks and Operational Principles

Parameter Optimization: The VQE Approach

The Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) operates on a hybrid quantum-classical framework where a parameterized quantum circuit (ansatz) prepares trial wavefunctions on a quantum processor [4]. The core computational workflow involves:

- Cost Function Definition: The energy expectation value ( C(\theta) = \langle \Psi(\theta) | O | \Psi(\theta) \rangle ) serves as the cost function, where ( O ) represents the molecular Hamiltonian and ( \Psi(\theta) ) is the parameterized trial wavefunction [4].

- Classical Optimization: A classical optimizer (e.g., BFGS, Adam) iteratively adjusts circuit parameters ( \theta ) to minimize the energy expectation value [4].

- Ansatz Dependency: Performance heavily depends on ansatz choice, with popular options including the Unitary Coupled-Cluster (UCC) ansatz for chemical applications [4].

Subspace Representation: Quantum Subspace Methods

Subspace methods construct an effective Hamiltonian within a smaller subspace of the full Hilbert space, then diagonalize it classically to find eigenstates and energies [20] [5]. Key variations include:

- Contextual Subspace VQE (CS-VQE): Identifies and isolates the most strongly correlated orbitals into a smaller active subspace, reducing quantum resource requirements while maintaining accuracy [5].

- Qumode Subspace VQE (QSS-VQE): Embeds qubit Hamiltonians into the infinite-dimensional Fock space of bosonic modes, using displacement and SNAP gates to construct variational ansätze [21].

- Subspace Diagonalization Methods: Construct the Hamiltonian matrix within a carefully selected subspace, then perform classical diagonalization to obtain ground and excited states simultaneously [20].

Table 1: Fundamental Operational Principles Comparison

| Feature | Parameter Optimization (VQE) | Subspace Representation |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Variational optimization of parameterized quantum circuits | Projection of problem into smaller subspace followed by diagonalization |

| Quantum Resource | Direct execution of parameterized circuits on quantum hardware | Quantum device used to prepare subspace basis states |

| Classical Component | Classical parameter optimization | Classical diagonalization of subspace Hamiltonian |

| Ansatz Dependency | High - performance sensitive to ansatz choice | Lower - relies on subspace selection rather than specific ansatz |

| Theoretical Guarantees | Limited - heuristic optimization with barren plateau risks | Rigorous complexity bounds and convergence guarantees available [20] |

Performance Comparison in Molecular Systems

Accuracy in Challenging Chemical Systems

The dissociation curve of molecular nitrogen (Nâ‚‚) presents a rigorous test due to strong static correlation effects at bond-breaking. In minimal basis set (STO-3G) simulations:

- CS-VQE Performance: Contextual Subspace VQE maintains good agreement with Full Configuration Interaction (FCI) energies across the entire dissociation curve (0.8Ã… to 2.0Ã…), outperforming single-reference methods like CCSD and CCSD(T) in the dissociation limit [5].

- Traditional VQE Limitations: Standard VQE implementations struggle with bond dissociation where multi-configurational character dominates, unless using specifically designed ansätze with sufficient expressivity [5].

- Multireference Capability: Subspace methods naturally capture strong correlation effects by including multiple determinant states in the active space, avoiding the symmetry-breaking issues of Unrestricted Hartree-Fock (UHF) [5].

Quantum Resource Requirements and Scalability

Resource efficiency determines practical applicability on near-term quantum devices:

- Qubit Requirements: CS-VQE reduces qubit counts by isolating correlated orbitals, enabling treatment of larger active spaces within fixed qubit constraints [5]. QSS-VQE offers exponential space compression by representing N qubits in a single bosonic mode truncated at ( L=2^{N_Q} ) Fock states [21].

- Circuit Depth: QSS-VQE achieves high expressivity with lower circuit depth through hardware-native bosonic operations (displacement and SNAP gates), outperforming qubit-based VQE with significantly deeper circuits for comparable accuracy [21].

- Measurement Overhead: Adaptive subspace selection can provide exponential reduction in required measurements compared to uniform sampling [20].

Table 2: Performance Comparison for Molecular Nitrogen Dissociation (STO-3G Basis)

| Method | Equilibrium Accuracy (Error vs. FCI) | Dissociation Limit Accuracy | Qubit Requirements | Notable Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VQE (UCC Ansatz) | ~Chemical accuracy achievable | Poor with single-reference ansätze | Scales with molecular orbitals | Barren plateaus, ansatz design challenges |

| CS-VQE | Good agreement with FCI [5] | Excellent agreement with FCI [5] | Reduced via subspace selection | Subspace identification critical |

| CCSD | High accuracy around equilibrium [5] | Fails qualitatively at dissociation [5] | Classical simulation | Breakdown for strongly correlated systems |

| CASSCF | Good accuracy | Good accuracy with proper active space | Classical exponential scaling | Active space selection sensitivity |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Contextual Subspace VQE Implementation

The experimental protocol for CS-VQE calculation of molecular nitrogen dissociation curve [5]:

System Preparation:

- Molecular geometry: Nâ‚‚ bond distances from 0.8Ã… to 2.0Ã…

- Basis set: STO-3G minimal basis

- Active subspace selection using MP2 natural orbitals

Error Mitigation Strategy:

- Dynamical Decoupling for coherence preservation

- Measurement-Error Mitigation

- Zero-Noise Extrapolation

- Circuit parallelization for passive noise-averaging

Ansatz Construction:

- Modified adaptive ansatz (qubit-ADAPT-VQE)

- Hardware-aware transpilation for target qubit topology

- Qubit-Wise Commuting (QWC) decomposition for measurement reduction

Quantum Processing:

- Hardware: Superconducting quantum processor

- Measurement: Photon number-resolved readout for bosonic variants [21]

Traditional VQE Workflow

Standard VQE implementation for molecular systems [4]:

Hamiltonian Formulation:

- Molecular Hamiltonian in second quantization

- Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev transformation to qubit space

- Qubit Hamiltonian expressed as Pauli terms

Ansatz Selection:

- UCCSD for chemical accuracy

- Hardware-efficient ansätze for reduced depth

- Problem-inspired ansätze for specific systems

Optimization Loop:

- Quantum circuit execution for energy/gradient estimation

- Classical parameter update using optimizers (BFGS, Adam, SPSA)

- Convergence check against chemical accuracy threshold (1.6 mHa/43 meV)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Computational Tools for Quantum Molecular Simulations

| Tool/Component | Function | Implementation Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Hamiltonians | Encodes system energy landscape | Electronic structure in second quantization [4] [5] |

| Active Space Selection | Identifies strongly correlated orbitals | MP2 natural orbitals, correlation entropy maximization [5] |

| Error Mitigation Suite | Counters NISQ device imperfections | Dynamical decoupling, zero-noise extrapolation, measurement error mitigation [5] |

| Classical Optimizers | Adjusts quantum circuit parameters | BFGS, Adam, SPSA for parameter optimization [4] |

| Subspace Diagonalization | Solves projected quantum problem | Classical eigensolvers for subspace Hamiltonian [20] |

| Bosonic Gate Sets | Implements continuous-variable operations | Displacement and SNAP gates in cQED hardware [21] |

| Potassium;manganese(2+);sulfate | Potassium;manganese(2+);sulfate, CAS:21005-91-4, MF:KMnO4S+, MW:190.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 4-acetylbenzo[d]oxazol-2(3H)-one | 4-Acetylbenzo[d]oxazol-2(3H)-one|CAS 70735-79-4 | High-purity 4-Acetylbenzo[d]oxazol-2(3H)-one (CAS 70735-79-4) for research. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

Application to Drug Development and Molecular Design

Quantum subspace methods offer particular advantages for pharmaceutical research:

- Reaction Pathway Mapping: Adaptive subspace selection achieves exponential reduction in measurements for transition-state mapping of chemical reactions, crucial for predicting drug metabolism pathways [20].

- Excited-State Calculations: QSS-VQE efficiently targets excited states using weighted cost functions (( w0 \gg w1 \gg \ldots )), enabling photochemical property prediction for photosensitive pharmaceuticals [21].

- Strong Correlation Handling: CS-VQE maintains accuracy for multiconfigurational systems common in transition metal complexes and radical intermediates in drug metabolism [5].

Parameter optimization and subspace representation offer complementary strengths for molecular quantum simulation. Parameter optimization methods (VQE) provide intuitive physical interpretability through specific ansätze but face challenges with barren plateaus and computational overhead. Subspace representation methods deliver rigorous theoretical guarantees, reduced quantum resource requirements, and robust performance for strongly correlated systems, but depend critically on effective subspace selection [20] [5].

For drug development professionals, subspace methods currently offer more practical pathways for investigating complex molecular phenomena within NISQ hardware constraints. The reduced quantum resource requirements, combined with advanced error mitigation, enable larger active space treatments essential for pharmacologically relevant molecules. As quantum hardware matures, hybrid approaches combining optimal subspace selection with efficient parameter optimization may ultimately deliver the full promise of quantum computational chemistry.

Algorithms for the Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) Era

The Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) era, a term coined by John Preskill, is characterized by quantum processors containing from 50 to approximately 1000 qubits that operate without full fault tolerance [22] [23]. These devices are inherently limited by noise sources such as decoherence, gate errors, and measurement errors that accumulate during computation, severely restricting the depth and complexity of executable quantum circuits [24] [22]. In this constrained environment, designing algorithms that can deliver useful results despite hardware limitations has become a central challenge for the quantum computing community. Two prominent algorithmic approaches have emerged for tackling quantum chemistry problems, particularly the calculation of molecular energies and properties: the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) and quantum subspace methods. These hybrid quantum-classical algorithms strategically leverage the respective strengths of quantum and classical processors, offering promising paths toward demonstrating quantum utility for molecular systems research with direct implications for drug development and materials science [22] [25].

Algorithmic Frameworks: Subspace Methods vs. VQE

Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE)

The Variational Quantum Eigensolver operates on the variational principle of quantum mechanics, which states that the expectation value of any trial wavefunction provides an upper bound to the true ground state energy [22]. The algorithm constructs a parameterized quantum circuit (ansatz) |ψ(θ)⟩ to approximate the ground state of a molecular Hamiltonian Ĥ, with the energy expressed as E(θ) = ⟨ψ(θ)|Ĥ|ψ(θ)⟩ [22]. In practice, the quantum processor prepares the ansatz state and measures the Hamiltonian expectation value, while a classical optimizer iteratively adjusts the parameters θ to minimize this energy [1] [22]. This hybrid approach leverages quantum superposition to explore exponentially large molecular configuration spaces while relying on well-established classical optimization techniques. The performance of VQE critically depends on several factors including ansatz choice, parameter initialization, and optimizer selection, with chemically-inspired ansätze like UCCSD often combined with adaptive optimizers showing superior convergence and precision [26].

Quantum Subspace Methods

Quantum subspace methods, particularly the Contextual Subspace Variational Quantum Eigensolver (CS-VQE), represent a resource-reduction strategy that addresses key limitations of standard VQE [5]. This approach partitions the full molecular problem into a smaller, highly correlated "contextual subspace" that is solved on the quantum computer, while the remaining degrees of freedom are treated classically [5]. By focusing quantum resources only on the most challenging correlation effects, the method enables the treatment of larger active spaces for a fixed qubit allowance and reduces the circuit depth and measurement requirements [5]. The contextual subspace is typically selected using classical heuristics such as MP2 natural orbitals to identify the orbitals with occupation numbers deviating most strongly from 0 or 2, thereby maximizing the correlation entropy captured in the quantum computation [5].

Comparative Performance Analysis

Quantum Resource Requirements

Table 1: Quantum resource comparison for molecular simulations

| Resource Metric | Standard VQE Approach | Contextual Subspace VQE | Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Qubit Count | 2M for M active spatial orbitals | Reduced via classical-quantum partition | Enables larger active spaces for fixed qubit count [5] |

| Circuit Depth | Full Hamiltonian implementation | Focused on contextual subspace | Shallower circuits, reduced noise sensitivity [5] |

| Measurement Overhead | Polynomial scaling with qubits | Reduced through Qubit-Wise Commuting decomposition | Improved sampling efficiency [5] |

| Error Mitigation Effectiveness | Limited by full circuit depth | Enhanced by parallelization and noise averaging | Better resilience to NISQ hardware noise [5] |

Algorithmic Performance Benchmarks

Table 2: Performance comparison for molecular nitrogen dissociation curve

| Performance Metric | Standard VQE | Contextual Subspace VQE | Classical Benchmarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy vs FCI | Varies with ansatz | Good agreement across dissociation curve | CASCI/CASSCF competitive but resource-intensive [5] |

| Static Correlation Handling | Limited by ansatz expressivity | Excellent in dissociation limit | Single-reference methods (ROHF, CCSD) break down [5] |

| Hardware Demonstration | Multiple small molecules | Nâ‚‚ in STO-3G basis on superconducting hardware | Reference values for comparison [5] |

| Resource Scaling | Exponential for exact representation | Polynomial reduction via subspace selection | CAS methods scale exponentially with active space [5] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

CS-VQE Implementation for Molecular Nitrogen

The experimental demonstration of CS-VQE for calculating the potential energy curve of molecular nitrogen represents one of the most comprehensive NISQ-era quantum chemistry implementations to date [5]. The methodology integrated multiple advanced techniques to overcome hardware limitations:

- Contextual Subspace Selection: The active subspace was selected using MP2 natural orbitals, focusing quantum resources on the most strongly correlated orbitals [5].

- Hardware-Aware Ansatz Construction: A modified qubit-ADAPT-VQE algorithm incorporated hardware awareness through a penalizing contribution in the excitation pool scoring function, minimizing transpilation costs for the target qubit topology [5].

- Measurement Reduction: Qubit-Wise Commuting (QWC) decomposition of the reduced Hamiltonians enabled parallel measurement of compatible terms, significantly reducing measurement overhead [5].

- Error Mitigation/Supression Strategy: A comprehensive approach combined Dynamical Decoupling, Measurement-Error Mitigation, and Zero-Noise Extrapolation to enhance result accuracy [5].

- Circuit Parallelization: Strategic parallelization provided passive noise-averaging and improved effective shot yield, further reducing measurement requirements [5].

Standard VQE Optimization Protocols

For standard VQE implementations, optimization protocol selection significantly impacts performance:

- Optimizer Selection: Comparative studies have examined various classical optimizers including gradient descent, SPSA, and ADAM, with adaptive methods generally showing superior convergence [26].

- Parameter Initialization: Research indicates that parameter initialization plays a decisive role in algorithm stability and convergence speed [26].

- Ansatz Architecture: The choice between chemically-inspired ansätze (UCCSD, k-UpCCGSD) and hardware-efficient ansätze represents a key trade-off between physical meaning and hardware feasibility [26].

- Gradient Estimation: Quantum-native gradient estimation techniques like the Parameter-Shift Rule provide exact gradients but incur measurement overhead, leading to developments like the QN-SPSA+PSR method that combines computational efficiency with precise gradient computation [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential components for NISQ-era quantum chemistry experiments

| Tool/Component | Function/Purpose | Implementation Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Error Mitigation Suite | Compensates for hardware noise without full error correction | Zero-noise extrapolation, measurement error mitigation, dynamical decoupling [5] |

| Hardware-Aware Compilers | Transpiles quantum circuits to respect hardware connectivity and limitations | Topology-aware mapping, gate decomposition to native gates [24] [5] |

| Classical Optimizers | Adjusts variational parameters to minimize energy | SPSA, ADAM, gradient descent, quantum natural gradient [1] [26] |

| Ansatz Libraries | Parameterized quantum circuit templates for wavefunction approximation | UCCSD, k-UpCCGSD, hardware-efficient, qubit-ADAPT [26] [5] |

| Measurement Reduction Tools | Minimizes measurement overhead through term grouping | Qubit-Wise Commuting (QWC) decomposition, classical shadow techniques [5] |

| Quantum Resource Estimators | Projects resource requirements for scaling to larger systems | Quantum resource estimation (QRE) frameworks [24] |

| 4-methoxy-N-(1-phenylethyl)aniline | 4-methoxy-N-(1-phenylethyl)aniline, CAS:2743-01-3, MF:C15H17NO, MW:227.307 | Chemical Reagent |

| 4-Methylbenzylidene-4-methylaniline | 4-Methylbenzylidene-4-methylaniline|CAS 16979-20-7 | 4-Methylbenzylidene-4-methylaniline is a Schiff base for materials science research. This product is for research use only and not for human consumption. |

The comparative analysis of quantum subspace methods and standard VQE approaches reveals a strategic trade-off facing researchers in the NISQ era. Standard VQE offers a direct approach to molecular simulation but faces significant challenges in scalability and noise resilience due to its substantial quantum resource requirements [24] [22]. Conversely, quantum subspace methods like CS-VQE introduce a sophisticated algorithmic framework that strategically partitions the computational burden between quantum and classical processors, enabling more efficient use of limited quantum resources [5]. For drug development professionals and research scientists targeting molecular systems, this comparison suggests that subspace methods currently offer a more practical path to meaningful results on existing hardware, particularly for challenging problems like bond dissociation where static correlation dominates [5]. As quantum hardware continues to evolve toward the fault-tolerant era, with industry roadmaps projecting increasingly capable devices, the lessons learned from both approaches will inform the development of next-generation quantum algorithms for molecular systems research [27] [28].

Implementing Quantum Algorithms for Real-World Molecular Systems

Simulating fermionic systems, such as molecules, on a quantum computer requires an efficient mapping of fermionic states and operators to qubits and quantum gates. The Jordan-Wigner (JW) transformation is a foundational encoding method that maps fermionic creation and annihilation operators to strings of Pauli operators, thereby allowing fermionic states to be represented on a quantum processor [4]. However, for systems with a fixed number of particles, the standard JW encoding can be redundant in its qubit usage, prompting the development of more resource-efficient alternatives [29]. This guide objectively compares the performance of the Jordan-Wigner transformation with other contemporary fermion-to-qubit mappings, framing the discussion within the broader thesis of quantum subspace methods versus the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) for molecular systems research. We provide supporting experimental data and detailed methodologies to aid researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in selecting appropriate tools for quantum computational chemistry.

Fermion-to-Qubit Mappings: A Comparative Analysis

The following section provides a structured comparison of the core technical approaches for mapping fermionic operations to quantum circuits.

Core Encoding Schemes

| Encoding Scheme | Core Principle | Typical Qubit Count | Key Advantage | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jordan-Wigner (JW) [4] [29] | Maps fermionic operators to Pauli strings with phase relations encoded via (Z) gates. | (M) (equals number of modes) | Simple, general-purpose, and straightforward to implement. | Non-local string operations lead to (O(M)) gate complexity. |

| Bravyi-Kitaev [29] | Uses a binary tree structure to balance locality of occupation and parity information. | (M) (equals number of modes) | Offers improved locality over JW for some operations. | More complex transformation logic than JW. |

| Contextual Subspace (CS) [5] | A hybrid quantum-classical method; quantum computer calculates a correction within a relevant subspace. | Reduced (problem-dependent) | Dramatically reduces quantum resource requirements for larger problems. | Requires sophisticated classical pre-processing to identify the contextual subspace. |

| Succinct Encoding [29] | A "data structure" approach that compresses the Fock space for fixed particle number. | (\mathcal{I} + o(\mathcal{I}))¹ (near-optimal) | Optimal space usage with efficient gate operations for low particle number. | Efficiency is regime-dependent ((F = o(M))). |

¹ (\mathcal{I} = \lceil \log \binom{M}{F} \rceil), the information-theoretic lower bound for representing F fermions in M modes.

Performance Benchmarks

The choice of encoding directly impacts the practical performance of quantum algorithms, as measured by gate complexity and simulation accuracy.

Table 2: Algorithmic Performance and Resource Overhead

| Algorithm & Encoding | System / Use Case | Key Performance Metric | Experimental Result / Scaling |

|---|---|---|---|

| VQE with JW [4] | Hâ‚‚ molecule (STO-3G basis) | Ground state energy calculation | Successful simulation; performance limited by long runtimes and limited parallelism on HPC systems. |

| CS-VQE [5] | Nâ‚‚ dissociation curve (STO-3G basis) | Accuracy vs. Full CI Energy | Outperformed single-reference methods (ROHF, MP2, CISD, CCSD, CCSD(T)); competitive with multiconfigurational CASCI/CASSCF. |

| Joint Measurement Scheme [30] | Estimating molecular Hamiltonians | Gate depth on a 2D lattice (Jordan-Wigner) | Depth: (O(N^{1/2})), Two-qubit gates: (O(N^{3/2})). Offers improvement over classical shadows. |

| Succinct Encoding [29] | Second-quantized systems ((F=o(M))) | Gate complexity of fermionic rotations | (O(\mathcal{I})) gate complexity, a polynomial improvement over some prior succinct encodings. |

Experimental Protocols: Methodologies for Benchmarking

To ensure reproducibility and provide a clear framework for evaluation, this section details the experimental protocols from key studies cited in this guide.

The following workflow outlines the experimental procedure for calculating the potential energy curve of molecular nitrogen using the CS-VQE method.

Figure 1: CS-VQE workflow for molecular nitrogen simulation.

- System Definition: The potential energy curve (PEC) for the Nâ‚‚ molecule was calculated at ten bond lengths between 0.8 Ã… and 2.0 Ã…, using the STO-3G minimal basis set [5].

- Contextual Subspace Selection: The full molecular Hamiltonian was classically reduced. A contextual subspace was selected using MP2 natural orbitals to maximize the correlation entropy captured within a manageable qubit count [5].

- Ansatz Construction: A hardware-aware variational ansatz was constructed using a modified qubit-ADAPT-VQE algorithm. The modification incorporated a penalty in the excitation pool scoring function to minimize transpilation costs for the target qubit topology [5].

- Quantum Execution & Optimization: The VQE routine was executed on a superconducting quantum processor. Each run involved many state preparations and measurements to optimize the circuit parameters.

- Error Mitigation: A comprehensive error suppression strategy was deployed, comprising:

- Dynamical Decoupling to suppress qubit decoherence.

- Measurement Error Mitigation to correct readout errors.

- Zero-Noise Extrapolation to estimate the result in the zero-noise limit [5].

- Classical Post-Processing: The quantum results were combined with the classically computed components to produce the final energy estimate for the full problem.

This protocol describes an alternative to VQE that uses informationally complete measurements to build a subspace for spectral calculations.

- Root State Preparation: A quantum circuit prepares a "root state" ( \rho_0 ), which is an approximation of the target ground state. This state is prepared on the quantum processor.

- Informationally Complete Measurement: Instead of measuring specific observables, the root state is subjected to a randomized measurement protocol, specifically classical shadows. This involves applying random unitaries before measuring in the computational basis, creating a classical snapshot of the quantum state [31].

- Subspace Expansion: A subspace is constructed classically by applying a set of ( L ) Hermitian expansion operators ( \sigmai ) (e.g., low-weight Pauli operators or powers of the Hamiltonian) to the classical shadow of ( \rho0 ). The expanded state is ( \rho{\text{SE}}(\vec{c}) = W^\dagger \rho0 W / \text{Tr}[W^\dagger \rho0 W] ), where ( W = \sum{i=1}^L ci \sigmai ) [31].

- Classical Diagonalization: The Hamiltonian and overlap matrices (( \mathcal{H} ) and ( \mathcal{S} )) are constructed within the expanded subspace using the classical shadow data. The ground state energy is found by solving the generalized eigenvalue problem ( \mathcal{H} \vec{c} = \lambda \mathcal{S} \vec{c} ) on a classical computer [31].

- Constrained Optimization: To handle numerical instability from shot noise, the eigenvalue problem is reformulated as a constrained optimization problem, providing rigorous statistical error bars for the energy estimate [31].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

This section catalogs key computational tools and methodologies essential for conducting advanced fermionic simulations on quantum hardware.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Quantum Computational Chemistry

| Tool / Technique | Category | Primary Function | Relevance to Molecular Simulation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jordan-Wigner Transform | Fermion Encoding | Maps fermionic operators to qubit operators. | The baseline method for translating molecular Hamiltonians from second quantization to a form executable on a quantum computer [4]. |

| Classical Shadows [31] | Measurement Protocol | An informationally complete method for estimating many observables from a single set of measurements. | Dramatically reduces the measurement overhead required for algorithms like Quantum Subspace Expansion (QSE). |

| Contextual Subspace [5] | Resource Reduction | A hybrid quantum-classical method that reduces the quantum resource requirements. | Enables the treatment of larger active spaces for a fixed qubit count, making larger molecules accessible on current hardware. |

| Qubit-ADAPT-VQE [5] | Ansatz Construction | A hardware-aware, adaptive algorithm for building variational ansätze. | Minimizes circuit depth by constructing ansätze that are naturally suited to the connectivity of the target quantum processor. |

| Dynamical Decoupling [5] | Error Suppression | Suppresses qubit decoherence by applying sequences of pulses. | A passive error suppression technique that improves the fidelity of quantum circuits without additional measurement overhead. |

| Zero-Noise Extrapolation [5] | Error Mitigation | Extrapolates results from noisy circuits to an estimate of the noiseless value. | Allows for more accurate energy estimations from computations performed on noisy quantum hardware. |

| (2-Methyl-1,4-dioxan-2-yl)methanol | (2-Methyl-1,4-dioxan-2-yl)methanol|C6H12O3 | (2-Methyl-1,4-dioxan-2-yl)methanol (CAS 1847423-96-4), a versatile cyclic acetal building block for organic synthesis. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

| 4-(Furan-2-yl)aniline hydrochloride | 4-(Furan-2-yl)aniline hydrochloride|1170462-44-8 | Bench Chemicals |

The search for the optimal way to map molecular problems to qubits is central to the progress of quantum computational chemistry. The Jordan-Wigner transformation remains a vital, general-purpose tool, but its resource requirements have spurred the development of more advanced encodings like the succinct encodings and hybrid methods like the Contextual Subspace approach [5] [29].

The experimental data and protocols presented here underscore a broader trend in the field: a shift from pure variational strategies (VQE) towards quantum-classical hybrid methods that leverage classical processing more powerfully. While VQE directly optimizes a parameterized quantum circuit, methods like CS-VQE and QSE with classical shadows use the quantum processor to generate a small but critical amount of data, which is then processed extensively classically to obtain high-accuracy results [5] [31]. This paradigm shows promise in mitigating the limitations of current hardware, such as noise and limited connectivity, and has already demonstrated capabilities for systems of up to 80 qubits [31]. For researchers in drug development and molecular science, this evolving toolkit offers a promising, if still maturing, path towards solving electronically complex problems that are classically intractable.

The Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) is a leading hybrid quantum-classical algorithm designed to find the ground-state energy of quantum systems, such as molecules, making it highly relevant for material science and drug discovery [1] [5]. Its hybrid nature leverages quantum computers to prepare and measure complex trial quantum states, while classical computers optimize the parameters of the quantum circuit to minimize the energy expectation value [4]. This makes VQE a promising algorithm for the current era of Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) devices [1].

The performance and accuracy of VQE critically depend on two core building blocks: the parameterized quantum circuit, known as the ansatz, and the classical optimizer [32] [11]. The choice of ansatz defines the expressiveness of the trial wavefunctions and the quantum resources required, while the classical optimizer determines the efficiency and robustness of the parameter search [26]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these building blocks, grounded in recent experimental studies, and frames their performance within the evolving context of quantum subspace methods.

Comparative Analysis of Ansatz Architectures

The ansatz is a parameterized quantum circuit responsible for preparing trial wavefunctions. Its structure is pivotal for successfully approximating the true ground state of a molecule.

Common Ansatz Types and Their Characteristics

Table 1: Comparison of Common VQE Ansatz Types

| Ansatz Type | Key Principle | Strengths | Weaknesses | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UCCSD (Unitary Coupled Cluster Singles and Doubles) | Chemistry-inspired; based on classical coupled-cluster theory [4] [5]. | High accuracy for molecular ground states [32]. | Can lead to deep quantum circuits, challenging on NISQ devices [32]. | Most stable & precise results for Si atom when paired with ADAM optimizer [32]. |

| Hardware-Efficient Ansatz (HEA) | Designed to minimize gate count and depth using native device gates [32]. | Reduced circuit depth, more resilient to noise [32]. | May struggle with representing complex molecular correlations [32]. | Crucial for near-term devices due to limited coherence times [32]. |

| k-UpCCGSD (k-Unitary Pair Coupled Cluster Generalized Singles and Doubles) | A variant of coupled cluster that reduces circuit depth [26]. | Balance between accuracy and quantum resource requirements [26]. | Less studied than UCCSD; performance can be system-dependent. | Benchmarked for silicon ground state energy estimation [26]. |

| ParticleConservingU2 | Designed to conserve the number of particles in the system [32]. | Built-in physical constraints, robust performance [32]. | Architecture may be less familiar than UCCSD. | Remarkably robust across all tested optimizers for Si atom [32]. |

Key Findings from Ansatz Benchmarking

Recent systematic benchmarking on the silicon atom reveals that chemically inspired ansatzes, particularly UCCSD and ParticleConservingU2, generally yield superior convergence and precision [32]. The UCCSD ansatz, when combined with an adaptive optimizer, delivered the most robust and precise ground-state energy estimations for silicon [32]. However, a critical trade-off exists between an ansatz's expressiveness and its practicality on near-term hardware. More expressive ansatzes like UCCSD require deeper circuits, making them more susceptible to noise, while hardware-efficient ansatzes offer shallower circuits at the potential cost of accuracy [32].

Comparative Analysis of Classical Optimizers