Quantum Theory in Drug Discovery: From Atomic Structure to Molecular Interactions

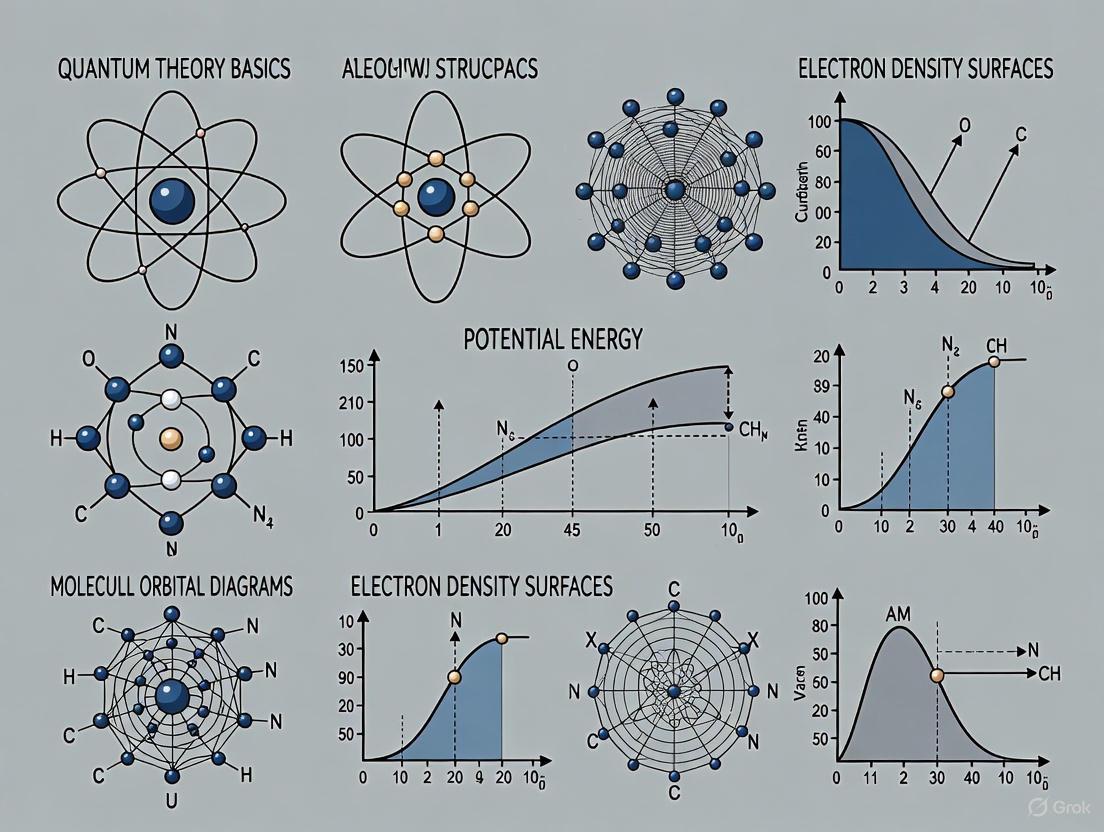

This article provides a comprehensive guide to quantum theory fundamentals and their critical applications in pharmaceutical research and development.

Quantum Theory in Drug Discovery: From Atomic Structure to Molecular Interactions

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to quantum theory fundamentals and their critical applications in pharmaceutical research and development. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the quantum mechanical principles governing atomic structure and chemical bonding, examines computational methodologies like QM/MM and their implementation in drug design workflows, addresses common challenges and optimization strategies in quantum chemistry applications, and validates quantum approaches against classical methods through case studies and emerging trends. The content bridges theoretical concepts with practical applications in target identification, lead optimization, and overcoming 'undruggable' targets, while looking ahead to the transformative potential of quantum computing in molecular simulation.

Quantum Foundations: From Schrödinger's Equation to Chemical Bonds

The Bohr model of the atom, proposed by Niels Bohr in 1913, represented a significant step forward in atomic theory by introducing the concept of quantized electron energy levels. This model successfully explained the discrete spectral lines of hydrogen but possessed critical limitations. It depicted electrons as orbiting the nucleus in fixed, planar paths akin to planets around a sun, a description fundamentally at odds with observed atomic behavior. The Bohr model failed to account for the spectra of heavier atoms, the Heisenberg uncertainty principle, and the wave-particle duality of electrons. Its inability to explain chemical bonding and the three-dimensional distribution of electron density in molecules rendered it inadequate for the needs of modern chemistry and drug development research.

The quantum mechanical model of the atom, developed in the mid-1920s, emerged as the definitive framework that superseded the Bohr model. This model abandons the concept of defined electron orbits, replacing it with a probabilistic description based on the wave-like nature of particles. It provides a comprehensive and accurate theory for atomic structure across all elements of the periodic table and forms the indispensable foundation for understanding molecular structure, chemical reactivity, and the interaction of matter with light. For researchers in drug development, this framework is not merely academic; it underpins modern computational chemistry methods used in molecular docking, ligand-protein interaction modeling, and rational drug design by accurately describing the electron distributions that govern all chemical phenomena [1].

The Core Principles of the Quantum Mechanical Model

The quantum mechanical model is built upon several foundational principles that distinguish it from classical and semi-classical predecessors like the Bohr model.

Wave-Particle Duality and the Schrödinger Equation

A cornerstone of quantum mechanics is wave-particle duality, which states that entities like electrons exhibit both particle-like and wave-like properties. The behavior of such particles is described by a wave function (ψ), a mathematical function that contains all the information that can be known about a quantum system. The time-independent Schrödinger equation formulates this relationship:

Hψ = Eψ

Here, H is the Hamiltonian operator, representing the total energy of the system, ψ is the wave function, and E is the quantized energy eigenvalue. Solving this equation for an atom yields specific wave functions and their corresponding energies, defining the atomic orbitals [1]. Unlike the Bohr model, this approach does not predict a precise electron path. Instead, the square of the wave function (|ψ|²) provides a probability density map, defining regions in three-dimensional space where an electron is most likely to be found [1].

The Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle

Formulated by Werner Heisenberg, this principle establishes a fundamental limit to the precision with which certain pairs of physical properties can be known simultaneously. For an electron, it means that the more precisely its position is determined, the less precisely its momentum can be known, and vice versa. This is not a limitation of measurement instruments but a fundamental property of quantum systems. This principle directly contradicts the Bohr model's assertion of electrons having well-defined orbits and momenta at all times [1] [2].

Atomic Orbitals and Quantum Numbers

The solution to the Schrödinger equation for the hydrogen atom introduces atomic orbitals. These are three-dimensional regions where there is a high probability of finding an electron, characterized by a set of four quantum numbers that arise from the mathematics of the solution. Each electron in an atom is uniquely described by its set of quantum numbers, as summarized in Table 1 [1].

Table 1: The Four Quantum Numbers of the Quantum Mechanical Model

| Quantum Number | Symbol | Describes | Allowed Values | Example for a 2p orbital |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Principal | n | Energy level (shell) and average distance from the nucleus | n = 1, 2, 3, ... | n = 2 |

| Azimuthal (Angular Momentum) | l | Orbital shape (subshell) | l = 0, 1, 2, ... , n-1 | l = 1 |

| Magnetic | mâ‚— | Orbital orientation in space | mâ‚— = -l, ..., 0, ..., +l | mâ‚— = -1, 0, +1 |

| Spin | mₛ | Intrinsic spin of the electron | mₛ = +½ or -½ | mₛ = +½ |

The spatial distribution of these orbitals (s, p, d, f), defined by their quantum numbers, dictates how atoms interact and form bonds, making them critical for predicting molecular geometry.

Methodologies: Computational and Experimental Protocols

The theoretical framework of quantum mechanics is brought to life through sophisticated computational and experimental methods that provide the data driving modern research.

Computational Workflow for High-Precision Atomic Data

The generation of high-precision atomic data, such as energy levels and transition rates, relies on a well-defined computational pipeline. A representative workflow, as implemented by the University of Delaware's atomic data portal, is visualized below and involves solving the many-electron Schrödinger equation using advanced approximation methods [3].

Diagram: Automated workflow for generating high-precision atomic data, from system definition to publication on an online portal.

Key computational methods include:

- Hartree-Fock (HF) Method: Provides an initial approximation by treating electrons as moving in an average field of other electrons.

- Post-Hartree-Fock Methods: These methods account for electron correlation, the correction to the mean-field approximation. Key approaches include:

- Configuration Interaction (CI): Constructs the wave function as a linear combination of electron configurations.

- Coupled-Cluster (CC) Theory: A highly accurate method for modeling electron correlation, using an exponential wave function ansatz [3].

- Relativistic Coupled-Cluster (All-Order) Method: Extends coupled-cluster theory to include relativistic effects, which are crucial for heavy elements [3].

This automated pipeline allows for the large-scale generation of atomic properties with estimated uncertainties, which are then made publicly available through online data portals for use by the research community [3].

Experimental Validation via Atomic Spectroscopy

While computational models are powerful, they require experimental validation. Atomic spectroscopy serves as the primary experimental protocol for this purpose. The process involves:

- Sample Excitation: An atom is excited (e.g., by heating or electrical discharge), causing its electrons to jump to higher energy levels.

- Photon Emission: As electrons relax to lower energy levels, they emit photons of specific energies.

- Spectral Analysis: The emitted light is separated into its constituent wavelengths, creating an emission spectrum. Each line corresponds to a transition between two quantized energy levels.

- Data Comparison: The measured wavelengths and intensities of spectral lines are compared against theoretical predictions from computational models. High-precision measurements of transition rates and energies, often stored in databases like the NIST Atomic Spectra Database, are used to benchmark and refine theoretical methods [3].

For scientists working in fields requiring atomic-level understanding, a curated set of data resources and conceptual tools is essential.

Table 2: Essential Data Resources for Atomic and Molecular Research

| Resource Name | Data Type Provided | Key Features & Applications |

|---|---|---|

| UD Atomic Data Portal [3] | Energies, transition rates, lifetimes, polarizabilities, hyperfine constants. | High-precision data computed with relativistic coupled-cluster methods; includes uncertainty estimates; critical for atomic clock, plasma, and astrophysics research. |

| NIST Atomic Spectra Database [3] | Energies, spectral lines, transition probabilities. | Comprehensive compendium of experimentally measured and theoretically compiled data; primary standard for spectral line identification and calibration. |

| Atomic Data and Nuclear Data Tables [4] | Compilations of experimental and theoretical data. | Peer-reviewed tables and graphs on collision processes, energy levels, cross-sections; resource for fundamental nuclear and atomic physics. |

Theoretical Frameworks for Chemical Bonding Analysis

Understanding chemical bonding requires moving from isolated atoms to molecules. Several key theories, built upon the quantum mechanical model, are standard in a researcher's toolkit:

- Molecular Orbital (MO) Theory: Introduced by Mulliken and Hund, this theory constructs molecular orbitals as linear combinations of atomic orbitals (LCAO). It is the principal model for quantitative calculations of molecular properties and for general discussions of electronic structure [5].

- Valence Bond (VB) Theory: Developed by Heitler, London, Slater, and Pauling, this theory retains the concept of electron-pair bonds formed by the overlap of atomic orbitals. It provides a language that is still widely used, particularly in organic chemistry, for a qualitative understanding of molecules [5].

- Quantum Theory of Atoms in Molecules (QTAIM): Developed by Bader, this real-space approach uses topological analysis of the electron density to define atoms and chemical bonds in molecules. It provides a rigorous quantum-mechanical definition of molecular structure [6].

- Quantum Information Theory (QIT) in Bonding: A modern framework that uses concepts like orbital entanglement to quantify chemical bond strength and character. It offers a unifying perspective that can recover both Lewis and beyond-Lewis bonding structures, providing a rigorous, quantitative descriptor for fuzzy chemical concepts like aromaticity [7] [8].

Applications in Modern Scientific Research

The quantum mechanical model is not an abstract theory but the bedrock of numerous advanced research and technology fields.

Explaining the Periodic Table and Chemical Trends

The model provides the first-principles explanation for the structure of the periodic table. Electron configurations, derived from the Aufbau principle and quantum numbers, dictate elemental properties. It accurately predicts periodic trends such as atomic radius, ionization energy, and electronegativity, which are fundamental to understanding chemical reactivity and designing new compounds [1].

Chemical Bonding and Molecular Interactions

For drug development professionals, the application to chemical bonding is paramount. The model explains:

- Covalent Bond Formation: The stabilization that occurs when atomic orbitals overlap to form molecular orbitals, with electron density concentrated between nuclei [5].

- Molecular Geometry: The shapes of molecules are explained by the Valence Shell Electron Pair Repulsion (VSEPR) theory, which itself is a consequence of electron orbital shapes and Pauli repulsion [1].

- Intermolecular Forces: Non-covalent interactions like hydrogen bonding and van der Waals forces, which are critical for ligand-receptor binding and protein folding, have their origins in the quantum mechanical distributions of electron density and resulting electrostatic potentials.

Enabling Modern Technology and Research Fields

- Semiconductor Physics and Electronics: The design of transistors and integrated circuits relies on understanding the band structure of solids, which is derived from the quantum mechanical interactions of vast numbers of atoms [1] [2].

- Quantum Computing: Quantum bits (qubits) leverage superposition and entanglement. The control of quantum states in systems like trapped ions or superconducting circuits depends entirely on the precise understanding of their atomic energy levels [1] [2].

- Spectroscopy and Analytical Chemistry: Techniques such as NMR, MRI, and X-ray spectroscopy are used for molecular characterization and are interpreted through the lens of quantum mechanics [1].

- Material Science and Nanotechnology: The development of novel materials, including quantum dots, superconductors, and nanomaterials, is guided by quantum mechanical principles that describe electron confinement and behavior at the nanoscale [1].

Advanced Framework: Integrating Quantum Information Theory

The frontiers of chemical bonding research are increasingly leveraging tools from quantum information theory (QIT) to gain deeper insights. This framework allows for the quantification of bonding using rigorous, non-empirical descriptors.

A key concept is the use of Maximally Entangled Atomic Orbitals (MEAOs). This method involves a fully localized orbital basis whose entanglement patterns quantitatively recover both traditional two-center bonds and complex multicenter bonding (e.g., in aromatic systems or transition states). The strength of a bond can be indexed by its genuine multipartite entanglement (GME), providing a direct measure of the quantum correlations that constitute the bond [8].

This leads to the development of a global bonding descriptor function, Fbond, which synthesizes orbital-based energies (like the HOMO-LUMO gap) with entanglement measures derived from the electronic wave function. This unified descriptor captures both the energetic stability and the quantum correlational structure of a bond. Validation on small molecules like H₂, NH₃, and H₂O shows that Fbond can discriminate between different bonding regimes, spanning a 60–80-fold range in value, and exhibits systematic convergence with improved basis sets [7]. This QIT-based framework offers a powerful new pathway for understanding complex bonding phenomena in biologically relevant molecules and materials.

The Schrödinger equation is the fundamental governing equation of non-relativistic quantum mechanics, providing a complete mathematical description of the behavior and energies of electrons in atoms and molecules [1]. Developed by Erwin Schrödinger in 1926, this formulation marked a pivotal departure from earlier atomic models by treating electrons not as discrete particles in fixed orbits but as matter waves described by a wave function [9] [10]. This framework successfully incorporates the wave-particle duality of matter and naturally leads to the quantized energy levels that explain atomic spectra and the structure of the periodic table [11]. For researchers in atomic structure and chemical bonding, the Schrödinger equation provides the essential theoretical foundation for moving beyond qualitative models to precise, quantitative predictions of molecular behavior, bonding energies, and electronic properties—making it indispensable for advanced fields like drug design and materials science [1] [5].

Mathematical Formulation of the Schrödinger Equation

The Schrödinger equation exists in two primary forms: time-dependent and time-independent. The time-dependent Schrödinger equation describes how a quantum system evolves over time and is written as:

[ i \hbar \frac{\partial \Psi(\mathbf{r}, t)}{\partial t} = \left[ -\frac{\hbar^2}{2m} \nabla^2 + V(\mathbf{r}, t) \right] \Psi(\mathbf{r}, t) ]

where ( i ) is the imaginary unit, ( \hbar ) is the reduced Planck's constant, ( \Psi ) is the wave function of the system, ( m ) is the particle mass, ( \nabla^2 ) is the Laplacian operator, and ( V ) is the potential energy [12] [13].

For systems where the potential energy is time-independent (( V = V(\mathbf{r}) )), the wave function can be separated into spatial and temporal components. This leads to the time-independent Schrödinger equation, which is used for stationary states and has the form:

[ \left[ -\frac{\hbar^2}{2m} \nabla^2 + V(\mathbf{r}) \right] \psi(\mathbf{r}) = E \psi(\mathbf{r}) ]

or equivalently,

[ \hat{H} \psi = E \psi ]

where ( \hat{H} ) is the Hamiltonian operator, ( \psi(\mathbf{r}) ) is the time-independent wave function, and ( E ) is the total energy of the system [1] [12] [13]. The Hamiltonian represents the total energy operator, summing kinetic and potential energy terms.

Table 1: Components of the Time-Independent Schrödinger Equation

| Component | Mathematical Expression | Physical Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Hamiltonian Operator ((\hat{H})) | ( -\frac{\hbar^2}{2m} \nabla^2 + V(\mathbf{r}) ) | Total energy operator of the system |

| Kinetic Energy Term | ( -\frac{\hbar^2}{2m} \nabla^2 ) | Represents the kinetic energy of particles |

| Potential Energy Term | ( V(\mathbf{r}) ) | Environment-specific potential (e.g., Coulomb) |

| Wave Function (( \psi )) | ( \psi(\mathbf{r}) ) | Contains all quantum information of the system |

| Energy Eigenvalue (( E )) | ( E ) | Quantized energy of the stationary state |

The solutions to the time-independent equation are wave functions ( \psi ) that describe the stationary states of the system, with the corresponding values of ( E ) representing the quantized energy levels that the system can occupy [12] [13].

Figure 1: Mathematical framework of the Schrödinger equation showing the relationship between its components.

Physical Interpretation and Solutions

The Wave Function and Probability Interpretation

The solution to the Schrödinger equation is the wave function, denoted by ( \Psi ) or ( \psi ), which contains all the information about the quantum state of a system [14] [13]. While the wave function itself has no direct physical meaning, its square modulus ( |\psi(\mathbf{r})|^2 ) represents the probability density of finding a particle at a specific location ( \mathbf{r} ) [11] [13]. For a single particle in one dimension, the probability of finding the particle between positions ( x ) and ( x+dx ) is given by ( |\psi(x)|^2 dx ). This probabilistic interpretation, first proposed by Max Born, represents a fundamental shift from classical determinism to quantum probability [1] [14].

The wave function must satisfy specific mathematical conditions to be physically reasonable: it must be single-valued, continuous, and its first derivative must also be continuous [13]. Additionally, the wave function must be square-integrable, meaning the integral of ( |\psi|^2 ) over all space must be finite, allowing it to be normalized to represent a probability of 1 that the particle exists somewhere in space [12].

Atomic Orbitals and Quantum Numbers

For electrons in atoms, the solutions to the Schrödinger equation under a Coulomb potential are the atomic orbitals, which describe three-dimensional probability distributions where electrons are most likely to be found [9] [11]. These solutions are characterized by three quantum numbers that emerge naturally from the mathematics of solving the equation:

- Principal quantum number (( n )): Determines the main energy level and size of the orbital (( n = 1, 2, 3, \ldots )) [9] [11]

- Angular momentum quantum number (( l )): Determines the shape of the orbital (( l = 0, 1, 2, \ldots, n-1 )) [11]

- Magnetic quantum number (( ml )): Determines the orientation of the orbital in space (( ml = -l, -l+1, \ldots, 0, \ldots, l-1, l )) [11]

A fourth quantum number, the spin quantum number (( m_s )), with possible values of ( +\frac{1}{2} ) or ( -\frac{1}{2} ), is required to fully describe an electron's state, though it does not derive directly from the Schrödinger equation [1] [10].

Table 2: Quantum Numbers from Schrödinger Equation Solutions

| Quantum Number | Symbol | Allowed Values | Physical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Principal | ( n ) | 1, 2, 3, ... | Determines energy level and orbital size |

| Angular Momentum | ( l ) | 0, 1, 2, ..., n-1 | Determines orbital shape (s, p, d, f) |

| Magnetic | ( m_l ) | -l, -l+1, ..., l-1, l | Determines spatial orientation |

| Spin | ( m_s ) | +1/2, -1/2 | Electron spin direction (added empirically) |

The shapes of atomic orbitals are determined by the angular part of the wave function solution: s-orbitals (( l=0 )) are spherical, p-orbitals (( l=1 )) are dumbbell-shaped, and d-orbitals (( l=2 )) have more complex cloverleaf shapes [15] [11]. The radial part of the solution describes how the probability density changes with distance from the nucleus, often showing characteristic nodes where the probability drops to zero [15].

Application to Atomic Systems and Chemical Bonding

The Hydrogen Atom Solution

The Schrödinger equation can be solved exactly for the hydrogen atom, where a single electron experiences the Coulomb potential ( V(r) = -\frac{e^2}{4\pi\epsilon_0 r} ) due to the nucleus [11] [13]. The solutions yield the familiar hydrogen atomic orbitals (1s, 2s, 2p, etc.) and perfectly reproduce the quantized energy levels previously obtained by Bohr:

[ En = -\frac{me e^4}{8\epsilon_0^2 h^2 n^2} = -\frac{13.6 \text{ eV}}{n^2} ]

This agreement with experimental data validated the Schrödinger equation as the correct description of atomic structure [11]. Unlike the Bohr model, which imposed quantization rules arbitrarily, the Schrödinger equation naturally produces quantized states through the requirement that the wave function must be single-valued and continuous [14].

Methodological Framework for Multi-Electron Systems

For multi-electron atoms and molecules, the Schrödinger equation becomes increasingly complex due to electron-electron repulsion terms, requiring approximation methods. The fundamental approach involves these key methodologies:

Born-Oppenheimer Approximation: Separates nuclear and electronic motion by treating nuclei as fixed in position, allowing solution of the electronic Schrödinger equation for specific nuclear configurations [5].

Orbital Approximation: Treats electrons as occupying individual orbitals, leading to the Hartree-Fock method and self-consistent field (SCF) approaches for approximating multi-electron wave functions [1].

Basis Set Expansion: Molecular orbitals are constructed as linear combinations of atomic orbitals (LCAO), with the choice of basis set (STO-3G, 6-31G, etc.) balancing computational accuracy and cost [7].

Potential Energy Surface Mapping: By solving the electronic Schrödinger equation at multiple nuclear configurations, researchers construct potential energy surfaces that determine molecular geometry, stability, and reactivity [5].

Figure 2: Computational workflow for solving the Schrödinger equation in molecular systems.

Chemical Bonding Theories

The Schrödinger equation provides the foundation for modern theories of chemical bonding:

Molecular Orbital Theory: Constructs delocalized orbitals that extend over entire molecules by combining atomic orbitals, with bonding and antibonding interactions determined by wave function symmetry and overlap [5].

Valence Bond Theory: Describes bonds as arising from the overlap of half-filled atomic orbitals, with electron pairing between adjacent atoms [5].

Modern Computational Approaches: Density Functional Theory (DFT) and variational quantum eigensolver (VQE) methods provide practical computational frameworks for solving the Schrödinger equation for complex molecules, enabling accurate prediction of molecular properties and reactivities relevant to drug design [7].

Research Applications and Protocols

Experimental and Computational Methodologies

The application of the Schrödinger equation in chemical research involves both computational and theoretical approaches:

Electronic Structure Calculation Protocol:

- System Preparation: Define molecular geometry, either from experimental data or preliminary calculations

- Method Selection: Choose appropriate computational method (HF, DFT, MP2, CCSD(T)) based on accuracy requirements and system size

- Basis Set Selection: Select basis set balancing accuracy and computational cost (e.g., 6-31G* for organic molecules)

- Energy Calculation: Solve the electronic Schrödinger equation iteratively until self-consistency is achieved

- Property Evaluation: Extract molecular properties (dipole moments, vibrational frequencies, excitation energies) from the wave function

- Bonding Analysis: Perform population analysis, calculate bond orders, and visualize molecular orbitals and electron density [7]

Bond Dissociation Energy Protocol:

- Calculate total energy of the molecule

- Calculate total energy of the dissociation products

- Account for zero-point vibrational energy corrections

- Compute energy difference to obtain bond strength [5]

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Quantum Chemical Calculations

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Basis Sets | STO-3G, 6-31G*, cc-pVDZ | Mathematical functions representing atomic orbitals |

| Quantum Chemistry Packages | Gaussian, GAMESS, PySCF, Q-Chem | Software for solving molecular Schrödinger equation |

| Wave Function Methods | Hartree-Fock, MP2, CCSD(T) | Mathematical approaches for electron correlation |

| Density Functionals | B3LYP, PBE0, ωB97X-D | Functionals for electron exchange and correlation in DFT |

| Visualization Tools | GaussView, Avogadro, VMD | 3D visualization of molecular orbitals and electron density |

Advanced computational frameworks now integrate quantum information theory with traditional quantum chemistry, introducing concepts like entanglement entropy and quantum correlation measures to provide deeper insights into chemical bonding beyond traditional energetic and orbital descriptions [7].

Advanced Concepts and Research Frontiers

Quantum Information Concepts in Chemical Bonding

Recent research has begun integrating quantum information theory with the Schrödinger equation framework to develop more comprehensive bonding descriptors. One approach formulates a global bonding descriptor function, ( F_{\text{bond}} ), that synthesizes traditional orbital-based descriptors with entanglement measures derived from the electronic wave function [7]. This framework employs:

- Maximally Entangled Atomic Orbitals (MEAOs): To identify bonding patterns

- Genuine Multipartite Entanglement (GME): To quantify quantum correlations inherent in chemical bonds

- Information-Theoretic Measures: Combined with traditional orbital energies (e.g., HOMO-LUMO gaps) to create unified descriptors capturing both energetic stability and quantum correlational structure [7]

Studies implementing this framework using variational quantum eigensolvers (VQE) have demonstrated its effectiveness across different bonding regimes, from strongly correlated covalent bonds in H₂ to more mean-field bonding character in NH₃ [7].

Emerging Applications in Drug Discovery and Materials Science

The predictive power of the Schrödinger equation enables several advanced applications:

Reaction Pathway Prediction: Mapping potential energy surfaces to identify transition states and reaction mechanisms relevant to biochemical processes [5]

Drug-Receptor Interactions: Calculating binding energies and electronic properties of ligand-receptor complexes through QM/MM (quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics) approaches

Spectroscopic Property Calculation: Predicting NMR chemical shifts, vibrational frequencies, and electronic excitation energies for compound characterization

Materials Design: Engineering electronic properties of semiconductors, catalysts, and nanomaterials through computational screening of candidate structures [1]

The continued development of more accurate and efficient methods for solving the Schrödinger equation ensures that quantum mechanics remains the foundational framework for understanding and predicting molecular behavior across chemical, biological, and materials sciences.

The quantum mechanical model of the atom fundamentally revolutionized our understanding of electron behavior by replacing classical deterministic orbits with probabilistic descriptions based on wave functions. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of atomic orbitals and quantum numbers, detailing how these concepts define electron probability distributions and serve as the foundation for predicting chemical bonding behavior. By establishing the critical relationship between quantum numbers and spatial electron density, this framework enables researchers to model molecular interactions with unprecedented accuracy, with direct applications in rational drug design and materials science.

The quantum mechanical model represents the most accurate description of atomic structure available today, superseding earlier planetary models like Bohr's by treating electrons as wave-like entities described by probability distributions rather than following fixed paths [1]. This model originates from the solution of the Schrödinger equation, which introduced the fundamental concept of atomic orbitals—three-dimensional regions where electrons are most likely to be found [16] [11].

At the heart of this theory lies the wave function (ψ), a mathematical description of an electron's wavelike behavior. The square of the wave function, ψ², provides the electron probability density at any point in space, defining the likelihood of locating an electron at specific coordinates [16] [17]. This probabilistic interpretation, first proposed by Max Born, represents a fundamental departure from classical mechanics and provides the theoretical underpinning for all modern computational chemistry approaches [1].

Quantum Numbers: Defining Electron States

Each electron within an atom is uniquely described by a set of four quantum numbers that emerge as mathematical solutions to the Schrödinger equation. These parameters specify the electron's energy, spatial distribution, and orientation, completely defining its quantum state [18] [19].

Table 1: The Four Quantum Numbers and Their Significance

| Quantum Number | Symbol | Allowed Values | Physical Significance | Determines |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Principal | n | 1, 2, 3, ... | Energy and distance from nucleus | Shell, orbital size |

| Azimuthal | l | 0, 1, 2, ..., n-1 | Orbital shape and angular momentum | Subshell, number of angular nodes |

| Magnetic | mâ‚— | -l, ..., 0, ..., +l | Spatial orientation | Number of orbitals in subshell |

| Spin | mₛ | +½, -½ | Electron spin direction | Magnetic properties |

Principal Quantum Number (n)

The principal quantum number defines the main energy level or electron shell and predominantly determines the orbital's energy and average distance from the nucleus [20] [18]. As n increases, the orbital becomes larger, extends farther from the nucleus, and contains more nodes—regions of zero electron probability [17]. For hydrogen-like atoms, the energy is determined solely by n according to the equation En = -13.61 eV (Z/n)² [16].

Azimuthal Quantum Number (l)

Also known as the orbital angular momentum quantum number, l determines the shape of the orbital and identifies the subshell within a principal shell [20] [19]. The value of l ranges from 0 to n-1, with each integer value corresponding to a specific orbital type: s (l=0), p (l=1), d (l=2), and f (l=3) [18]. This quantum number also determines the number of angular nodes, which equals the value of l [18].

Magnetic Quantum Number (mâ‚—)

The magnetic quantum number specifies the orientation of an orbital in three-dimensional space [20] [11]. For a given value of l, mâ‚— can take integer values from -l to +l, resulting in 2l+1 possible orientations [18]. This quantum number explains how atomic orbitals respond to external magnetic fields and determines the number of orbitals within each subshell [19].

Spin Quantum Number (mâ‚›)

Independent of the other three quantum numbers, the spin quantum number describes the intrinsic angular momentum of the electron [20] [18]. With possible values of +½ (spin-up) or -½ (spin-down), this quantum number explains the magnetic properties of atoms and enforces the Pauli Exclusion Principle, which states that no two electrons in an atom can have identical quantum numbers [18] [19].

Figure 1: Hierarchical relationship between quantum numbers showing how principal quantum number constrains azimuthal quantum number, which in turn determines the range of magnetic quantum numbers. Spin quantum number operates independently.

Atomic Orbitals and Probability Distributions

Atomic orbitals represent three-dimensional probability distributions derived from the solutions to the Schrödinger equation [16]. Each orbital type exhibits characteristic shapes, nodal patterns, and radial distributions that directly influence chemical bonding behavior [17].

Table 2: Characteristics of Atomic Orbitals

| Orbital Type | Azimuthal Quantum (l) | Number of Orientations | Nodal Planes | Shape Description | Maximum Electron Capacity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| s | 0 | 1 | 0 | Spherically symmetric | 2 |

| p | 1 | 3 | 1 | Dumbbell-shaped with two lobes | 6 |

| d | 2 | 5 | 2 | Four-lobed or cloverleaf | 10 |

| f | 3 | 7 | 3 | Complex multi-lobed structure | 14 |

Radial and Angular Probability Distributions

The electron probability distribution can be separated into radial and angular components, providing complementary information about electron localization [20] [17].

Radial Distribution Function: This describes the probability of finding an electron at a specific distance from the nucleus, regardless of direction [17]. Calculated as 4πr²Rₙₗ²(r)dr, where Rₙₗ(r) is the radial wave function, this distribution reveals shell structure with peaks corresponding to the most probable electron distances [16] [17]. The number of radial nodes equals n - l - 1 [20].

Angular Distribution Function: This component, derived from Yₗₘ(θ,φ), determines the directional characteristics and basic shape of the orbital [20]. The angular distribution depends only on quantum number l and is responsible for the directional properties of p, d, and f orbitals that critically influence molecular geometry [20] [16].

Orbital Shapes and Nodal Properties

- s Orbitals: Spherically symmetrical with maximum electron density at the nucleus [19]. As n increases, s orbitals develop spherical nodes where electron probability drops to zero [17].

- p Orbitals: Dumbbell-shaped with two lobes separated by a nodal plane where electron probability is zero [20] [19]. The three p orbitals (pₓ, pᵧ, p_z) orient along perpendicular axes [19].

- d Orbitals: Feature more complex four-lobed geometries with two nodal planes [20]. Their directional characteristics significantly influence transition metal bonding and coordination chemistry [19].

- f Orbitals: Exhibit the most complex shapes with seven orientations and three nodal planes, particularly relevant in lanthanide and actinide chemistry [19].

Figure 2: Decomposition of electron probability distribution into radial and angular components, showing how each contributes to the overall electron density.

Experimental Methodologies and Visualization Techniques

Spectroscopic Determination of Orbital Energies

Atomic emission and absorption spectroscopy provide experimental verification of quantized energy levels predicted by quantum numbers [1]. When electrons transition between orbitals characterized by different n values, they emit or absorb photons with energies corresponding to ΔE = E₂ - E₠= hν [1]. Modern techniques include:

- Photoelectron Spectroscopy: Directly measures orbital ionization energies by ejecting electrons with high-energy photons [1]

- X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy: Probes core electron transitions to characterize unoccupied orbitals [1]

Computational Quantum Chemistry Methods

Advanced computational approaches solve the Schrödinger equation for multi-electron systems:

- Hartree-Fock Method: Approximates electron-electron repulsion using self-consistent field theory [1]

- Density Functional Theory (DFT): Calculates electron distribution and energy using electron density functionals [1]

- Ab Initio Calculations: Solves molecular systems from first principles without empirical parameters [5]

Orbital Visualization Protocols

- Wave Function Plots: Generated by fixing two coordinates and plotting ψ variation with the third variable [16]

- Electron Density Plots: Display ψ² on specific planes using color intensity to represent probability density [16]

- Orbital Isosurfaces: 3D surfaces enclosing regions where ψ² exceeds a threshold value (typically 90% probability) [16]

- Radial Distribution Curves: Plots of 4πr²Rₙₗ²(r) versus distance r from nucleus [17]

Table 3: Key Computational and Experimental Resources for Orbital Analysis

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Methods | Primary Application | Key Information Provided |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Chemistry Software | Gaussian, GAMESS, NWChem | Molecular orbital calculations | Electron densities, orbital energies, bonding characteristics |

| Visualization Platforms | Avogadro, ChemCraft, Jmol | 3D orbital representation | Spatial orientation, nodal surfaces, phase relationships |

| Spectroscopic Instruments | XPS, UPS, AES | Experimental orbital energy measurement | Ionization potentials, orbital composition, oxidation states |

| Quantum Simulation | SpinQ Educational Quantum Computers | Hands-on quantum state manipulation | Experimental validation of quantum principles [1] |

| Theoretical Frameworks | DFT, Hartree-Fock, Post-Hartree-Fock | Multi-electron system modeling | Accurate electron correlation, binding energies, reaction pathways |

Applications to Chemical Bonding and Drug Discovery

The quantum mechanical description of atomic orbitals provides the fundamental basis for understanding chemical bonding [5] [21]. Molecular Orbital Theory directly extends atomic orbital concepts to describe bonding and antibonding interactions through orbital overlap and phase compatibility [5] [1].

In pharmaceutical research, orbital interactions determine:

- Molecular Recognition: Complementarity between drug and receptor orbitals [22]

- Reaction Mechanisms: Frontier orbital interactions (HOMO-LUMO) controlling biochemical reactions [1]

- Binding Affinity: Charge transfer complexes stabilized through orbital overlap [22]

- Stereoselectivity: Directional orbital interactions influencing chiral recognition [19]

The quantum mechanical model successfully explains why helium (1s²) exhibits zero valency while carbon can adopt promoted configurations (1s²2s¹2p³) to achieve tetravalency [22]. This understanding of valency based on unpaired electrons and orbital vacancies enables rational design of molecular scaffolds with predetermined connectivity [22].

Atomic orbitals and their defining quantum numbers provide the essential framework for understanding electron behavior in atoms and molecules. The probabilistic interpretation of electron distributions has revolutionized our approach to chemical bonding, enabling precise predictions of molecular structure and reactivity. For drug development professionals, this quantum mechanical foundation supports rational design strategies that optimize target engagement and selectivity through deliberate manipulation of orbital interactions. As computational methods continue advancing, increasingly sophisticated orbital-based models will further enhance our ability to design therapeutic agents with precision and predictive accuracy.

Wave-particle duality and the Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle are not merely abstract quantum concepts but are fundamental to predicting and understanding the behavior of matter at the molecular and atomic scales. Their implications directly shape the methodologies and limitations of modern molecular modeling. This whitepaper details how these quantum principles form the theoretical foundation for computational techniques—from valence bond theory to molecular dynamics simulations—that are crucial in fields such as drug discovery and materials science. By examining the core theories, their mathematical expressions, and their practical consequences for simulation, this guide provides researchers with a framework for interpreting computational results and understanding the inherent uncertainties in quantum-mechanical models of chemical bonding.

Theoretical Foundation

Wave-Particle Duality

Wave-particle duality describes the fundamental inability of classical concepts like "particle" or "wave" to fully describe the behavior of quantum-scale objects. These entities exhibit properties of both waves and particles, with the observable behavior depending on the experimental context [23] [24].

Historical Development: For light, the wave theory, validated by Thomas Young's interference experiments in 1801, was later challenged by Max Planck's black-body radiation law (1901) and Albert Einstein's explanation of the photoelectric effect (1905), which both indicated particle-like behavior [23]. For matter, the sequence of discovery was reversed. Electrons were initially understood as particles, as evidenced by J.J. Thomson's 1897 mass measurement [23]. Louis de Broglie later proposed in 1924 that all matter could exhibit wave-like behavior, with a wavelength given by λ = h/p, where h is Planck's constant and p is the momentum [25] [24]. This was experimentally confirmed in 1927 by Clinton Davisson, Lester Germer, and George Paget Thomson via electron diffraction experiments [23] [24].

Mathematical Formalism: The de Broglie relation quantitatively connects the particle property (momentum, p) with the wave property (wavelength, λ): λ = h / p [25]. This relationship implies that a particle with a well-defined momentum is described by a wave of well-defined wavelength, which is necessarily spread out over all space. This infinite wave cannot be localized in space, illustrating the intrinsic connection to the Uncertainty Principle.

Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle

The Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle establishes a fundamental limit on the precision with which certain pairs of physical properties can be simultaneously known [26] [27].

Core Principle: It states that the more precisely one property (e.g., position) is measured, the less precisely its conjugate pair (e.g., momentum) can be known. This is not a limitation of experimental instrumentation but rather a fundamental property of quantum systems arising from the wave-like nature of matter [28].

Mathematical Formulation: The most common expression relates the uncertainties in position (Δx) and momentum (Δp). The product of their standard deviations must be greater than or equal to half of the reduced Planck constant (ħ = h/2π) [26] [27] [28]: Δx Δp ≥ ħ/2 Similar relationships exist for other conjugate pairs, such as energy and time (ΔE Δt ≥ ħ/2) [28].

Table 1: Key Conjugate Pairs and Their Uncertainty Relations

| Conjugate Pair | Uncertainty Relation | Physical Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Position & Momentum | Δx Δp ≥ ħ/2 | A particle confined to a small region (small Δx) must have a highly uncertain momentum (large Δp). |

| Energy & Time | ΔE Δt ≥ ħ/2 | A quantum state with a short lifetime (small Δt) has a broad energy width (large ΔE). |

Implications for Molecular Modeling and Chemical Bonding

The principles of wave-particle duality and uncertainty directly dictate how electrons are described in molecules, forming the bedrock of all modern theories of chemical bonding.

From Atomic Orbitals to Chemical Bonds

The behavior of electrons in atoms and molecules is described by wavefunctions (Ψ), which are solutions to the Schrödinger equation [29]. The square of the wavefunction, |Ψ|², gives the probability density of finding an electron at a specific point in space [26]. This probabilistic description, an expression of the electron's wave nature, replaces the classical concept of a well-defined orbital path.

The Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle necessitates this probabilistic model. It makes it impossible to define a trajectory where both the position and momentum of an electron are known with arbitrary precision [29]. Consequently, atomic orbitals are visualized as three-dimensional probability clouds (s, p, d orbitals) defined by quantum numbers, rather than as fixed paths [29].

Table 2: Quantum Numbers and Atomic Orbitals

| Quantum Number | Symbol | Allowed Values | Describes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Principal | n | 1, 2, 3, ... | Orbital energy and size (shell) |

| Angular Momentum | l | 0, 1, 2, ... n-1 | Orbital shape (s, p, d, f subshells) |

| Magnetic | mâ‚— | -l, ..., 0, ..., +l | Orbital orientation in space |

| Spin | mâ‚› | +1/2, -1/2 | Intrinsic spin of the electron |

Theoretical Frameworks for Chemical Bonding

Two primary quantum mechanical theories, both acknowledging wave-particle duality, model the formation of chemical bonds:

Valence Bond (VB) Theory: Developed by Heitler, London, Slater, and Pauling, VB theory states that a covalent bond forms through the overlap of half-filled atomic orbitals from two atoms [5] [30]. The two electrons in the overlapping region must have paired spins (opposite directions), and the buildup of electron probability between the nuclei leads to a stable bond [5]. This theory directly uses the concept of orbital hybridization (mixing atomic orbitals) to explain molecular geometries [30].

Molecular Orbital (MO) Theory: Introduced by Mulliken and Hund, MO theory constructs orbitals that are delocalized over the entire molecule [5] [30]. Atomic orbitals combine to form molecular orbitals, which can be bonding (lower energy, electron density between nuclei) or antibonding (higher energy). Electrons are then filled into these molecular orbitals, following the Pauli exclusion principle and Hund's rule [30] [29]. MO theory more naturally accounts for the wave-like delocalization of electrons in molecules.

The following diagram illustrates the logical progression from quantum principles to modeling outcomes:

Figure 1: From Quantum Principles to Molecular Models

Practical Implications for Computational Methods

Uncertainty in Molecular Dynamics Simulations

Classical Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations, which track nuclear motion, are intrinsically chaotic and sensitive to initial conditions [31]. This necessitates rigorous Uncertainty Quantification (UQ) to produce reliable, actionable results, particularly in industrial applications like drug discovery [31].

Ensemble Methods: Because an individual simulation is inherently unpredictable, the standard UQ approach is to run a large ensemble of replicas with varying initial conditions. Reliable statistics and uncertainty estimates are then derived from this ensemble [31].

Systematic vs. Stochastic Error: Errors in MD fall into two categories:

- Systematic Errors: Introduced by approximations in the model, such as the choice and parameterization of the force field, which can bias results (e.g., favoring certain protein secondary structures) [31].

- Stochastic Errors: The random variation arising from the chaotic dynamics of the system. This is an intrinsic, irreducible uncertainty that must be characterized [31].

The Born-Oppenheimer Approximation

A critical approximation in quantum chemistry is the Born-Oppenheimer Approximation, which separates electronic and nuclear motion [5]. This is justified because nuclei are much heavier than electrons and move more slowly. The approximation allows for the solution of the electronic Schrödinger equation for fixed nuclear positions, generating a molecular potential energy surface [5]. The uncertainty principle underpins this separation by implying that the more localized, massive nuclei have greater positional certainty than the delocalized, light electrons over the timescales of nuclear motion.

Experimental Validation and Protocols

The theoretical frameworks of quantum mechanics are grounded in landmark experiments that validated wave-particle duality.

Key Historical Experiments

Table 3: Foundational Experiments on Wave-Particle Duality

| Experiment | System | Key Methodology | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Photoelectric Effect (Einstein, 1905) [23] | Light | Shining light of varying frequency onto a metal surface and measuring ejected electron energy. | Demonstrated light behaves as particles (photons); electron energy depends on frequency, not intensity. |

| Davisson-Germer Experiment (1927) [23] [25] | Electrons | Scattering a beam of electrons from a nickel crystal surface. | Observed diffraction patterns, conclusively demonstrating the wave nature of electrons. |

| Double-Slit Experiment (Electron) [23] | Electrons | Firing electrons one-by-one at a barrier with two slits and detecting their arrival position on a screen. | Single electrons build up an interference pattern over time, showing single entities exhibit wave behavior. |

Detailed Protocol: Conceptual Electron Double-Slit Experiment

This protocol outlines the procedure for demonstrating wave-particle duality of electrons [23].

Apparatus Setup:

- Electron Source: A source capable of emitting electrons, ideally with a very low intensity to emit electrons one at a time.

- Barrier with Double Slit: A thin, solid barrier with two closely spaced, parallel slits.

- Detector: A position-sensitive detector (e.g., a phosphorescent screen or a modern electron multiplier array) placed behind the slit barrier to record the arrival position of electrons.

Procedure:

- Step 1: With the electron source at low intensity, begin the experiment. Electrons are emitted and pass through the experimental apparatus.

- Step 2: Record the arrival position of each individual electron on the detector. Initially, these positions will appear random.

- Step 3: Allow the experiment to run for a sufficient duration, accumulating the data from thousands of individual electron detection events.

Expected Results and Analysis:

- The cumulative detection pattern will reveal a series of light and dark interference fringes. This is a signature of wave behavior.

- The fact that this pattern is built from discrete, localized impacts (particle-like) demonstrates that individual electrons exhibit wave-particle duality. The wave function (wave nature) describes the probability of where the electron (particle) will be detected.

The workflow for a modern computational study incorporating these principles is as follows:

Figure 2: Computational Workflow with Uncertainty Quantification

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents & Materials

The following table details key computational "reagents" and tools essential for performing molecular modeling informed by quantum principles.

Table 4: Essential Components for Molecular Modeling Simulations

| Item / Concept | Function / Role in Simulation |

|---|---|

| Force Field | A set of empirical functions and parameters that describe the potential energy of a system of particles; a primary source of systematic error that must be carefully chosen [31]. |

| Wavefunction (Ψ) | The central object in quantum mechanics, containing all information about a quantum system. Its square gives the electron probability density [29]. |

| Born-Oppenheimer Approximation | Allows the separation of electronic and nuclear motion, making the computation of molecular wavefunctions and potential energy surfaces tractable [5]. |

| Ensemble | A collection of a large number of replicas of a system used to obtain statistically meaningful averages and quantify random (stochastic) error [31]. |

| Periodic Boundary Conditions (PBCs) | A computational method to simulate a bulk system by treating a simulation cell as a repeating unit, minimizing finite-size effects. |

| Thermostat/Barostat | Algorithms that maintain constant temperature (thermostat) and pressure (barostat) during a simulation, ensuring proper thermodynamic sampling [31]. |

| victoria blue 4R(1+) | Victoria Blue 4R(1+) | Basic Blue 8 | For Research Use |

| 2-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)acetaldehyde | 2-(4-Hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)acetaldehyde|Homovanillin |

The quantum mechanical model of the atom represents the most advanced and accurate theory of atomic structure, fundamentally revolutionizing how we understand atoms and their interactions. Unlike classical models that depicted electrons in fixed orbits, this model describes the behavior of electrons in atoms using probability distributions and wave functions, marking a paradigm shift in physical chemistry. The framework is built upon key principles that distinguish it from classical mechanics: wave-particle duality (electrons exhibit both wave-like and particle-like properties), quantization of energy (electrons occupy discrete energy levels), and the Heisenberg uncertainty principle (which states that one cannot simultaneously measure both the position and momentum of an electron with absolute precision) [1] [32]. This theoretical foundation is not merely an abstract concept but forms the cornerstone of modern chemistry, materials science, and drug discovery, enabling researchers to predict molecular behavior, reactivity, and properties with remarkable accuracy. The direct influence of quantum theory on chemistry, beginning with the pioneering work of Heitler and London in 1927, established that the physical nature of chemical bonding is a quantum phenomenon that can only be understood through the quantum theory presented by Heisenberg and Schrödinger [33].

Atomic Orbitals: The Building Blocks

The Schrödinger Equation and Quantum Numbers

At the heart of the quantum mechanical model of the atom lies the Schrödinger equation, which describes how the quantum state of a physical system changes over time [29]. Solving this time-independent equation for an atom yields the wave function (ψ), which contains all the information about an electron's behavior [1]. The physical interpretation of the wave function's square (ψ²) describes the electron density distribution, representing the relative probability of finding an electron at a given point in space [29]. Each electron in an atom is uniquely described by a set of four quantum numbers that arise as solutions to the Schrödinger equation, as detailed in Table 1 [1] [29].

Table 1: Quantum Numbers Defining Electron States

| Quantum Number | Symbol | Allowed Values | Physical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Principal | n | 1, 2, 3, ... | Determines the energy level and overall size of the orbital |

| Angular Momentum | l | 0, 1, 2, ..., n-1 | Defines the shape of the orbital (s=0, p=1, d=2, f=3) |

| Magnetic | mâ‚— | -l, -l+1, ..., 0, ..., l-1, l | Specifies the orbital's orientation in space |

| Spin | mₛ | +½ or -½ | Represents the intrinsic spin direction of the electron |

Shapes and Energies of Atomic Orbitals

Atomic orbitals are classified into types based on their angular momentum quantum number (l), each with distinctive shapes and properties [1] [29]. The s orbitals (l=0) exhibit spherical symmetry centered around the nucleus. The p orbitals (l=1) display a dumbbell shape with two lobes and a nodal plane at the nucleus; the three degenerate p orbitals (pₓ, pᵧ, p_z) are oriented perpendicularly along their respective axes. The d orbitals (l=2) and f orbitals (l=3) possess more complex shapes with multiple lobes and nodal surfaces [29] [34]. For multi-electron atoms, orbital energies depend on both principal and angular momentum quantum numbers, following the order: 1s < 2s < 2p < 3s < 3p < 4s < 3d < 4p < 5s, with this energy progression dictating the order of orbital filling according to the Aufbau principle [29].

Figure 1: Atomic orbitals are characterized by their shapes and energy levels, which are determined by quantum numbers.

Theoretical Models of Chemical Bonding

Molecular Orbital Theory

Molecular orbital (MO) theory provides a comprehensive framework for understanding covalent bonding by describing electrons as delocalized throughout the entire molecule rather than localized between specific atoms [35]. This theory employs the linear combination of atomic orbitals (LCAO) approach, where atomic orbitals from different atoms combine mathematically through wave function addition to form molecular orbitals [35]. When atomic orbitals combine constructively (in-phase wave interference), a bonding molecular orbital forms, characterized by increased electron density between nuclei and lower energy than the original atomic orbitals, thereby stabilizing the molecule. When atomic orbitals combine destructively (out-of-phase wave interference), an antibonding molecular orbital forms, characterized by a nodal plane between nuclei and higher energy, which destabilizes the molecule [34] [35]. The bonding capacity is determined by the bond order, calculated as half the difference between the number of electrons in bonding and antibonding orbitals [35]. MO theory successfully explains phenomena that challenge other bonding models, such as the paramagnetism of molecular oxygen (O₂), which has two unpaired electrons in degenerate π* antibonding orbitals [35].

Valence Bond Theory

Valence bond (VB) theory offers a complementary perspective on chemical bonding, emphasizing the pairing of electrons in overlapping atomic orbitals [5]. Developed by Heitler, London, and extensively expanded by Slater and Pauling, this approach maintains the concept of localized bonds between specific atom pairs [33] [5]. In VB theory, a covalent bond forms when two atomic orbitals, one from each atom, overlap significantly, and the electrons they contain pair with opposite spins [5]. This orbital overlap creates a region of enhanced wave function amplitude between the nuclei, increasing electron density in the internuclear region and lowering the system's overall energy [5]. The theory naturally explains the directional nature of bonds through the spatial characteristics of the overlapping orbitals, particularly p and d orbitals with specific orientations. While VB theory effectively describes molecular geometries and bonding patterns in many organic compounds, it has been largely superseded by MO theory for quantitative computational chemistry due to the latter's more efficient computational implementation [33].

Table 2: Comparison of Bonding Theories in Quantum Chemistry

| Feature | Valence Bond (VB) Theory | Molecular Orbital (MO) Theory |

|---|---|---|

| Bond Localization | Considers bonds as localized between specific atom pairs | Treats electrons as delocalized over the entire molecule |

| Fundamental Process | Forms bonds through overlap of atomic orbitals | Combines atomic orbitals to form molecular orbitals |

| Bond Description | Creates σ or π bonds through orbital overlap | Creates bonding and antibonding interactions |

| Key Strength | Predicts molecular shape based on electron pairs | Explains magnetic properties and resonance fully |

| Primary Developers | Heitler, London, Pauling | Mulliken, Hund |

The Born-Oppenheimer Approximation

A critical approximation underlying both major bonding theories is the Born-Oppenheimer approximation, which separates the motion of electrons from that of atomic nuclei [5]. This separation is physically justified by the significant mass disparity between electrons and nuclei, with nuclei being thousands of times heavier and consequently moving much more slowly [5]. This approximation allows chemists to calculate molecular potential energy curves and surfaces, which show how a molecule's energy varies with nuclear positions [5]. The energy minimum of such a curve corresponds to the equilibrium bond length, while the depth of this minimum relates to the bond dissociation energy, providing quantitative insights into bond strength and stability [5].

Computational Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Quantum Chemical Computation Workflow

Modern computational quantum chemistry employs sophisticated methodologies to solve the molecular Schrödinger equation approximately. The standard protocol begins with the Born-Oppenheimer approximation to separate nuclear and electronic motions [5]. For the electronic Schrödinger equation, two primary computational approaches have emerged: wave function-based methods (including Hartree-Fock and post-Hartree-Fock methods) and density functional theory (DFT) [33]. The computational workflow typically involves: (1) Molecular geometry specification - defining initial nuclear positions; (2) Basis set selection - choosing appropriate mathematical functions to represent atomic orbitals; (3) Method selection - deciding on the theoretical approach (HF, DFT, MP2, CCSD(T), etc.); (4) Self-consistent field (SCF) calculation - iteratively solving for the electron distribution; and (5) Property calculation - deriving molecular properties from the converged wave function or electron density [1] [33].

Figure 2: Quantum chemical computations follow a systematic workflow to solve the molecular Schrödinger equation.

Quantum chemical calculations require specialized computational tools and theoretical resources, as detailed in Table 3.

Table 3: Essential Resources for Quantum Chemical Research

| Resource/Component | Function/Purpose | Examples/Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Basis Sets | Mathematical functions representing atomic orbitals for LCAO | STO-3G, 6-31G*, cc-pVDZ |

| DFT Functionals | Approximations for electron exchange and correlation effects | B3LYP, PBE0, ωB97X-D |

| Ab Initio Methods | Wave function-based computational approaches | Hartree-Fock, MP2, CCSD(T) |

| Thermochemical Data | Reference data for validation and comparison | NIST Chemistry WebBook, International Critical Tables |

| Software Packages | Implement quantum chemical algorithms | Gaussian, GAMESS, ORCA, Q-Chem |

Applications in Research and Drug Development

The quantum mechanical understanding of chemical bonding enables numerous applications across scientific disciplines and industrial sectors. In drug discovery and development, quantum chemistry provides insights into molecular recognition, binding interactions, and reaction mechanisms that are fundamental to pharmaceutical research [1]. Quantum methods facilitate molecular property prediction, allowing researchers to compute electronic properties, absorption spectra, and reactivity indices without synthetic effort [1] [34]. The principles of molecular orbital theory underpin rational drug design by elucidating intermolecular interactions, such as hydrogen bonding, π-π stacking, and charge-transfer complexes, that govern drug-receptor binding [1] [35]. Quantum chemical calculations enable reaction mechanism elucidation, providing atom-level understanding of biochemical transformations and metabolic pathways relevant to drug metabolism [1]. Additionally, the framework explains spectroscopic behavior, allowing researchers to interpret NMR, IR, and UV-Vis spectra for structural characterization of potential drug candidates [1] [32].

Beyond pharmaceutical applications, quantum principles drive innovations in material science through the design of semiconductors, superconductors, and nanomaterials with tailored electronic properties [1]. The field of quantum computing leverages these fundamental principles for developing quantum gates and error correction protocols [1]. Emerging technologies including quantum sensors, spintronics, and quantum cryptography all build upon the foundational insights provided by the quantum mechanical model of atoms and molecules [1].

The quantum mechanical description of atomic orbitals and molecular bonds represents one of the most successful theoretical frameworks in modern science, bridging the gap between fundamental physics and practical chemistry. By replacing the deterministic perspective of classical mechanics with a probabilistic model based on wave functions and orbitals, quantum theory provides an accurate, comprehensive explanation of chemical bonding and molecular structure. The continuing evolution of computational methodologies, particularly density functional theory, has transformed this conceptual framework into a powerful predictive tool that drives innovation across chemistry, materials science, and pharmaceutical research. As quantum chemistry continues to develop, particularly with advances in computational hardware and algorithmic sophistication, researchers and drug development professionals will increasingly rely on these fundamental principles to design novel materials, understand complex biological systems, and develop new therapeutic agents with greater precision and efficiency.

The concept of the chemical bond is the cornerstone of modern chemistry, essential for understanding molecular structure, stability, and reactivity. The advent of quantum mechanics in the early 20th century provided the tools to move beyond empirical models and develop a fundamental physical understanding of bonding. This led to the simultaneous development of two foundational quantum chemical theories: Valence Bond (VB) Theory and Molecular Orbital (MO) Theory [36] [37]. Both theories originate from the same quantum mechanical principles but offer different perspectives and mathematical approaches to describing how atoms combine to form molecules. Valence Bond theory, championed by Pauling, retained a more intuitive, chemical language closely related to Lewis's electron-pair bond [36] [37]. In contrast, Molecular Orbital theory, developed by Mulliken and Hund, provided a more delocalized, global perspective on molecular electronic structure [36] [38]. For researchers in drug development and materials science, understanding the strengths, limitations, and complementary nature of these two models is crucial for interpreting computational results and designing new molecules with targeted properties. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical comparison of VB and MO theories, detailing their theoretical foundations, computational methodologies, and modern applications.

Historical Development and Theoretical Foundations

The Genesis of Two Complementary Theories

The roots of Valence Bond theory trace back to G.N. Lewis's seminal 1916 paper, "The Atom and The Molecule," which introduced the concept of the covalent bond as a shared pair of electrons [36] [37]. This qualitative model was given a quantum mechanical foundation in 1927 by Walter Heitler and Fritz London, who provided the first quantum-mechanical solution for the hydrogen molecule (Hâ‚‚) [38] [37] [39]. Their work demonstrated that the covalent bond arises from the overlap and pairing of electrons in atomic orbitals between two atoms, with the stability of the molecule resulting from electrostatic interactions and quantum mechanical exchange energy [40] [39]. Linus Pauling later expanded these ideas into a comprehensive theory, introducing the pivotal concepts of resonance (1928) to describe molecules that cannot be represented by a single Lewis structure, and orbital hybridization (1930) to explain the geometry of polyatomic molecules [36] [37].

Concurrently, Molecular Orbital theory was developed through the work of Friedrich Hund, Robert Mulliken, and John Lennard-Jones [36] [38]. Unlike the localized bond picture of VB theory, MO theory proposed that atomic orbitals combine to form molecular orbitals that are delocalized over the entire molecule [41] [37]. This approach initially found greater utility in molecular spectroscopy [36]. The struggle for dominance between these theories, personified in the rivalry between Pauling and Mulliken, lasted for decades. VB theory, with its more chemical language, was dominant until the 1950s, after which it was eclipsed by MO theory due to the latter's simpler computational implementation and more successful prediction of properties like paramagnetism [36] [42]. Since the 1980s, however, advances in computing have facilitated a renaissance in VB theory, and it is now recognized that both theories, when applied at a high level of sophistication, converge to the same results [36] [37].

Core Principles and Mathematical Frameworks

The fundamental difference between the two theories lies in their initial construction of the molecular wavefunction.

Valence Bond Theory Approach: VB theory constructs the total wave function "in terms of antisymmetrized products of atom-centered orbitals... that represent the interaction of the atoms" [38]. It begins with the concept of isolated atoms and forms bonds by the pairing of electrons in overlapping atomic orbitals from adjacent atoms [40] [37]. A covalent bond is formed when two atoms, each contributing a singly occupied orbital, approach closely enough for their orbitals to overlap [43] [40]. The electron pair in the overlapping orbitals is attracted to both nuclei, bonding the atoms together. The theory adheres strictly to the electron-pair bond model and uses resonance to describe situations where a molecule must be represented as a superposition of multiple VB structures [36] [37]. To account for molecular geometry, VB theory uses hybridization, a mathematical mixing of atomic orbitals (e.g., s and p) on a single atom to create new directional hybrid orbitals (e.g., sp³, sp², sp) that maximize overlap during bond formation [40] [37].

Molecular Orbital Theory Approach: MO theory, in contrast, builds the wave function from "antisymmetrized products of MOs, delocalized orbitals that are usually linear combinations of atomic orbitals" [38]. Atomic orbitals (AOs) from all atoms in the molecule combine—either constructively or destructively—to form molecular orbitals that are spread across the entire molecule [44] [42]. This process is described mathematically by the Linear Combination of Atomic Orbitals (LCAO) method [44]. The combination of AOs results in a set of molecular orbitals equal in number to the original atomic orbitals. These MOs are classified as:

- Bonding MOs: Formed by in-phase (constructive) combination of AOs; lower in energy than the parent AOs, and concentrate electron density between nuclei, stabilizing the molecule.

- Antibonding MOs: Formed by out-of-phase (destructive) combination of AOs; higher in energy and characterized by a node between nuclei, destabilizing the molecule if occupied.

- Nonbonding MOs: Orbitals that remain largely localized on an atom and do not contribute significantly to bonding [44] [42].

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between the core concepts of each theory and their connection to molecular properties.

Theoretical Pathways to Molecular Properties

Comparative Analysis: Strengths, Limitations, and Predictive Power

The core differences in the approaches of VB and MO theory lead to distinct strengths and weaknesses in explaining molecular properties, particularly for challenging cases.

Key Differentiating Factors

- Bond Localization vs. Delocalization: VB theory treats bonds as localized between two atoms, while MO theory considers electrons to be delocalized in orbitals spanning the entire molecule [41] [42] [45].

- Orbital Basis: VB uses pure or hybridized atomic orbitals as its basis, emphasizing their overlap. MO theory uses molecular orbitals formed from AOs as its fundamental building blocks [41] [37].

- Handling of Resonance: In VB theory, resonance is a core concept requiring a superposition of multiple wavefunctions (Lewis structures) to describe a molecule [36] [37]. In MO theory, resonance is not needed; the delocalized nature of the MOs naturally accounts for the electron distribution described by resonance structures in VB [41].

- Aromaticity: VB theory explains aromaticity through the spin coupling of π orbitals, akin to resonance between Kekulé and Dewar structures. MO theory views it as the delocalization of π-electrons over a cyclic molecular orbital system [37].

The Paramagnetism of Oxygen: A Case Study

The oxygen molecule (Oâ‚‚) provides a classic example where MO theory succeeds where the simple VB model fails. The Lewis structure and simple VB model of Oâ‚‚ show all electrons paired, suggesting a diamagnetic molecule [42]. However, experiment shows liquid oxygen is paramagnetic and is attracted to a magnetic field, indicating the presence of unpaired electrons [44] [42].

MO theory correctly predicts this. The molecular orbital diagram for Oâ‚‚ shows that the two highest energy electrons reside in degenerate Ï€* antibonding orbitals. According to Hund's rule, these electrons remain unpaired, resulting in a triplet ground state (³Σgâ») with two unpaired electrons [44] [42]. This successful prediction was a major historical triumph for MO theory.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Valence Bond and Molecular Orbital Theories

| Aspect | Valence Bond (VB) Theory | Molecular Orbital (MO) Theory |

|---|---|---|

| Basic Concept | Overlap of atomic orbitals forming localized bonds between atom pairs [40] [37] [45]. | Combination of atomic orbitals to form molecular orbitals delocalized over the entire molecule [41] [44] [45]. |

| Bond Formation | Driven by pairing of electrons in overlapping orbitals (sigma, pi) [40] [37]. | Filling of molecular orbitals (bonding, non-bonding, antibonding) following Aufbau principle [44] [42]. |

| Treatment of Electrons | Localized between two specific atoms [41] [45]. | Delocalized across multiple nuclei [41] [44] [45]. |

| Key Strengths | Intuitive, explains molecular geometry via hybridization/VSEPR [40] [45]. Predicts correct homonuclear dissociation [37]. | Naturally explains delocalization, paramagnetism (Oâ‚‚), and spectroscopic properties [44] [42] [37]. |

| Key Limitations | Incorrectly predicts Oâ‚‚ diamagnetic [42] [45]. Qualitative description of resonance [36] [37]. | Early models incorrectly predicted dissociation of Hâ‚‚ into a mix of atoms and ions [37]. Less intuitive for molecular shape [44] [45]. |

| Computational Cost | Historically high due to non-orthogonal orbitals [41] [36]. | More computationally tractable, leading to wider adoption [41] [36]. |

Computational Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Modern computational chemistry relies on sophisticated implementations of both VB and MO theories, often using powerful software suites to solve the electronic Schrödinger equation for molecules.

Modern Computational Frameworks

Most mainstream quantum chemistry programs (e.g., GAUSSIAN, MOLPRO, GAMESS) are primarily based on the MO formalism due to its computational efficiency [38]. Standard methodologies include:

- Hartree-Fock (HF) Methods: The simplest MO-based approach, which uses a single Slater determinant as the wavefunction and treats electron correlation in an average, mean-field manner [38]. It can be Restricted (RHF) or Unrestricted (UHF) for open-shell systems.

- Post-Hartree-Fock Methods: These include Configuration Interaction (CI), Coupled Cluster (CC), and Multiconfigurational SCF (MCSCF) methods like Complete Active Space SCF (CASSCF). These methods introduce electron correlation by considering multiple electron configurations, which is essential for accurate descriptions of bond breaking and excited states [38].

- Density Functional Theory (DFT): A highly popular approach that uses the electron density rather than the wavefunction as the fundamental variable. While formally distinct, practical Kohn-Sham DFT computations are performed within an MO-like framework [38] [39].

Modern Valence Bond theory has also seen significant computational advances. Programs like CASVB can transform MO-based wavefunctions (from CASSCF) into a valence bond form, expressing them "in terms of optimized, non-orthogonal, atom-centered orbitals" [38]. The Generalized Valence Bond (GVB) method, a type of multiconfigurational wavefunction, is considered a bridge between VB and MO theories and can be viewed as a special form of MCSCF [41] [38].

Protocol for Bonding Analysis in Solids Using LOBSTER

Analyzing chemical bonding in periodic solids presents unique challenges, as electronic structures are often computed using plane-wave basis sets, which lack the atomic orbital basis required for traditional MO analysis. The LOBSTER package bridges this gap [39].

Aim: To perform a wavefunction-based bonding analysis for a crystalline solid, such as a carbonate material. Principle: A plane-wave density functional theory (DFT) calculation is performed first. The LOBSTER code then projects the resulting plane-wave wavefunctions onto a local atomic orbital basis (e.g., spd), enabling population analysis and bonding indicators [39].

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Bonding Analysis

| Tool / Method | Function | Theoretical Basis |

|---|---|---|

| Plane-Wave DFT Code (VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO) | Performs the initial electronic structure calculation for the periodic solid. | Density Functional Theory |