Quantum vs Classical Computing in Chemistry: The Scaling Advantage for Drug Discovery and Materials Science

This article explores the fundamental computational scaling differences between quantum and classical computers in chemical simulations.

Quantum vs Classical Computing in Chemistry: The Scaling Advantage for Drug Discovery and Materials Science

Abstract

This article explores the fundamental computational scaling differences between quantum and classical computers in chemical simulations. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it details how classical methods like Density Functional Theory (DFT) face exponential scaling limitations for complex quantum systems. In contrast, we examine how quantum algorithms, such as the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE), offer a pathway to polynomial scaling, enabling the accurate simulation of molecular interactions, drug-protein binding, and catalytic processes that are currently intractable. The article provides a comparative analysis of current hybrid quantum-classical applications, discusses the critical challenges of error correction and qubit fidelity, and validates recent demonstrations of unconditional quantum speedup, ultimately outlining a future where quantum computing shifts chemistry from a field of discovery to one of design.

The Exponential Wall: Why Classical Computing Fails in Quantum Chemistry

In computational chemistry, the simulation of molecular systems is fundamentally limited by the scaling behavior of classical algorithms. The core of the problem lies in the exponential growth of computational resources required to solve the Schrödinger equation for quantum systems as their size increases. While classical computational methods such as Density Functional Theory (DFT) and coupled cluster theory have provided valuable approximations for decades, they inevitably face intractable complexity when modeling complex quantum phenomena like strongly correlated electrons, transition metal catalysts, and excited states [1].

Quantum computing emerges as a transformative solution to this scaling problem. Since molecules are inherently quantum systems, quantum computers offer a natural platform for their simulation, theoretically capable of modeling quantum interactions without the approximations that plague classical methods [1]. This comparison guide examines how quantum computational approaches are beginning to overcome the exponential scaling barriers that constrain classical methods in chemistry research, with particular relevance to drug development and materials science.

Computational Scaling: A Quantitative Comparison

The table below summarizes the fundamental scaling differences between classical and quantum computational methods for key chemistry simulation tasks.

Table 1: Scaling Comparison of Classical vs. Quantum Computational Methods

| Computational Method | Representative Chemistry Problems | Computational Scaling | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exact Diagonalization (Classical) | Small molecule ground states | Exponential in electron number | Intractable beyond ~50 orbitals [2] |

| Density Functional Theory (Classical) | Molecular structures, properties | Polynomial (typically O(N³)) | Fails for strongly correlated electrons [1] |

| Coupled Cluster (Classical) | Reaction energies, spectroscopy | O(Nâ¶) to O(N¹â°) | Prohibitively expensive for large systems [1] |

| Variational Quantum Eigensolver (Quantum) | Molecular ground states, reaction paths | Polynomial quantum + classical overhead | Current noise limits qubit count/accuracy [3] [2] |

| Quantum Phase Estimation (Quantum) | Precise energy calculations, excited states | Polynomial with fault tolerance | Requires fault-tolerant qubits [1] |

The exponential scaling of exact classical methods becomes apparent when modeling specific chemical systems. For instance, simulating the iron-molybdenum cofactor (FeMoco) essential for nitrogen fixation was estimated to require approximately 2.7 million physical qubits on a quantum computer, reflecting the immense complexity that makes this problem classically intractable [1]. Similarly, cytochrome P450 enzymes central to drug metabolism present similar computational challenges that exceed the capabilities of classical approximation methods [1].

Experimental Protocols & Performance Data

Hybrid Quantum-Classical Supercomputing for Complex Molecular Systems

Experimental Protocol: A collaborative team from Caltech, IBM, and RIKEN developed a quantum-centric supercomputing approach to study the [4Fe-4S] molecular cluster, a complex quantum system fundamental to biological processes including nitrogen fixation [4]. Their methodology proceeded as follows:

- Problem Encoding: The electronic structure problem of the [4Fe-4S] cluster was mapped onto a quantum computer using up to 77 qubits of an IBM Heron quantum processor [4].

- Quantum-Guided Reduction: Instead of using classical heuristics to approximate the Hamiltonian matrix (which grows exponentially with system size), the quantum computer identified the most crucial components of this matrix [4].

- Classical Refinement: The reduced Hamiltonian, containing only the most significant elements as determined by the quantum processor, was transferred to the RIKEN Fugaku supercomputer for exact diagonalization and computation of the final wave function and energy levels [4].

Performance Data: This hybrid approach successfully computed the electronic energy levels of the [4Fe-4S] cluster, a system that has long been a benchmark target for demonstrating quantum advantage in chemistry. The research did not definitively surpass all classical methods but significantly advanced the state-of-the-art in applying quantum algorithms to problems of real chemical interest [4].

Large-Scale Quantum Simulation Using FAST-VQE

Experimental Protocol: Kvantify, in partnership with IQM, implemented the FAST Variational Quantum Eigensolver (FAST-VQE) algorithm on a 50-qubit IQM Emerald quantum processor to study the dissociation curve of butyronitrile [2]. The methodology featured:

- Algorithm Selection: FAST-VQE was chosen over other VQE variants like ADAPT-VQE because it maintains a constant circuit count as the chemical system grows, enabling better scalability [2].

- Active Space Selection: The simulation utilized an active space of 50 molecular orbitals, a size that exceeds the practical limits of classical complete active space (CAS) methods [2].

- Hybrid Execution: Adaptive operator selection was performed on the quantum device, while energy estimation was handled by a chemistry-optimized classical simulator [2].

- Optimization Strategy: A greedy optimization strategy (adjusting one parameter at a time) was employed to overcome the bottleneck of simultaneous parameter optimization, allowing 120 iterations per hardware slot compared to just 30 with the full-parameter approach [2].

Performance Data: The 50-qubit implementation demonstrated measurable advantages over random baseline approaches, with the quantum hardware achieving faster convergence despite noise [2]. The greedy optimization strategy delivered an energy improvement of approximately 30 kcal/mol over the full-parameter optimization method [2]. This experiment highlighted a crucial shift in scaling limitations: as quantum hardware matures, classical optimization is becoming the primary bottleneck in hybrid algorithms [2].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Recent Quantum Chemistry Experiments

| Experiment | Hardware Platform | Algorithm | System Studied | Key Performance Metric |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caltech/IBM/RIKEN [4] | IBM Heron (77 qubits) + Fugaku Supercomputer | Quantum-Centric Supercomputing | [4Fe-4S] molecular cluster | Successfully computed electronic energy levels of a previously intractable system |

| Kvantify/IQM [2] | IQM Emerald (50 qubits) | FAST-VQE | Butyronitrile dissociation | Achieved ~30 kcal/mol energy improvement with greedy optimization |

| IonQ Collaboration [5] | IonQ Forte | Quantum-Classical AFQMC | Carbon capture materials | Accurately computed atomic-level forces beyond classical accuracy |

| Google Quantum AI [6] | Willow processor | Quantum Echoes (OTOC) | Molecular structures via NMR | 13,000x speedup vs. fastest classical supercomputers |

Visualization of Workflows and Scaling Relationships

Computational Scaling Pathways

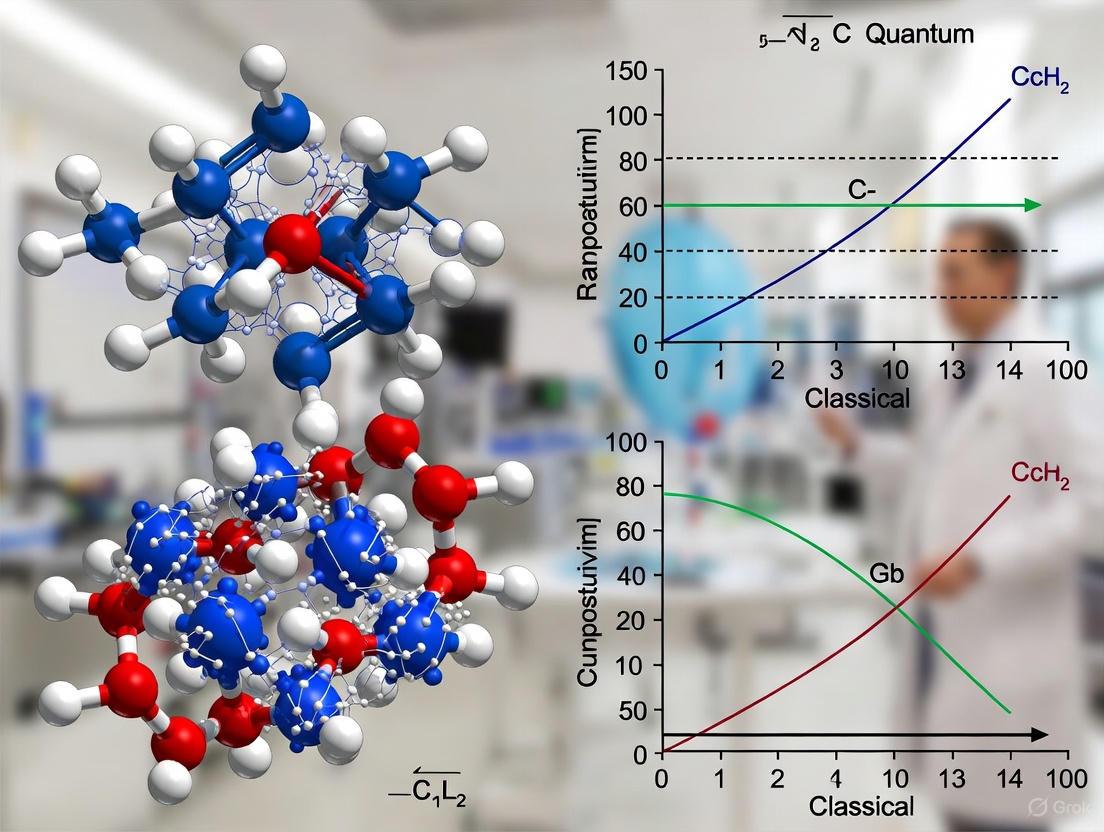

Figure 1: This diagram contrasts how classical and quantum computing resources scale with increasing chemical problem complexity. Classical methods face exponential resource growth, while quantum computing offers polynomial scaling.

Hybrid Quantum-Classical Workflow

Figure 2: The hybrid workflow used in modern quantum chemistry experiments, showing the iterative interaction between quantum and classical computing resources.

Table 3: Key Resources for Quantum Computational Chemistry Research

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Software Development Kits | Qiskit (IBM) [7] [8], Cirq (Google) [3], Qrunch (Kvantify) [2] | Provide tools for building, optimizing, and executing quantum circuits; enable algorithm development and resource management |

| Quantum Hardware Platforms | IBM Heron/Nighthawk [7], IQM Emerald [2], IonQ Forte [5] | Physical quantum processors for running chemical simulations; vary in qubit count, connectivity, and error rates |

| Quantum Algorithms | Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) [3], Quantum Approximate Optimization (QAOA) [3], Quantum-Classical AFQMC [5] | Specialized protocols for solving specific chemistry problems like ground state energy calculation and force estimation |

| Classical Co-Processors | High-Performance Computing clusters [7] [4], GPU accelerators | Handle computationally intensive classical components of hybrid algorithms, including error mitigation and parameter optimization |

| Error Mitigation Tools | Dynamic circuits [7], HPC-powered error mitigation [7], Zero-noise extrapolation | Improve result accuracy by suppressing and correcting for quantum processor noise and decoherence |

The experimental evidence demonstrates that quantum computing is progressively overcoming the exponential scaling problems that limit classical computational methods in chemistry. While today's quantum devices still face significant challenges in qubit count, connectivity, and error rates, the hybrid quantum-classical approaches demonstrated by leading research groups enable researchers to explore chemically relevant problems that were previously intractable [4] [2].

The field is rapidly advancing, with IBM projecting quantum advantage by the end of 2026 and fault-tolerant quantum computing by 2029 [7]. For researchers in chemistry and drug development, these developments signal a coming transformation in how molecular systems are simulated and understood. The ongoing collaboration between quantum hardware engineers, algorithm developers, and chemistry domain experts remains essential to fully realize the potential of quantum computing to solve chemistry's most challenging problems [9].

Limitations of Density Functional Theory (DFT) for Strongly Correlated Electrons

In the landscape of computational chemistry and materials science, the fundamental challenge revolves around the quantum mechanical many-body problem, whose computational complexity scales exponentially with system size. Density Functional Theory (DFT) has emerged as the cornerstone electronic structure method for quantum simulations across chemistry, physics, and materials science due to its favorable balance between accuracy and computational cost, typically scaling as O(N³) with system size. However, this favorable scaling comes at a significant cost: the method's accuracy is fundamentally limited by approximations in the exchange-correlation functional, a limitation that becomes critically pronounced in strongly correlated electron systems. These systems, characterized by competing quantum interactions that prevent electrons from moving independently, exhibit some of the most intriguing phenomena in condensed matter physics, including high-temperature superconductivity, colossal magnetoresistance, and metal-insulator transitions [10].

The core challenge lies in the failure of standard DFT functionals (LDA, GGA) to adequately capture the strong electron-electron interactions in these materials. While DFT succeeds tremendously for weakly correlated systems, its approximations fundamentally break down when electron localization and dynamic correlations dominate the physical behavior. This limitation has profound implications for drug development professionals and chemical researchers studying transition metal complexes, catalytic reaction centers, and quantum materials, where predictive accuracy is essential for rational design. This review systematically examines the theoretical origins, practical manifestations, and computational solutions for DFT's limitations in strongly correlated systems, providing researchers with a comprehensive framework for selecting appropriate methodologies beyond conventional DFT.

Fundamental Limitations of Standard DFT Approximations

The Self-Interaction Error and Electronic Delocalization

The foundational issue plaguing conventional DFT approximations is the self-interaction error (SIE), where an electron incorrectly interacts with itself. In exact DFT, this spurious self-interaction would precisely cancel, but approximate functionals fail to achieve this cancellation, leading to unphysical delocalization of electronic states. This error profoundly impacts predicted material properties, as evidenced in studies of europium hexaboride (EuB₆) where standard functionals fail to capture subtle symmetry breaking under pressure [11]. The SIE becomes particularly detrimental in strongly correlated materials containing localized d- and f-electrons, where electronic states should remain spatially confined due to strong Coulomb repulsion.

Standard DFT approximations tend to underestimate band gaps and predict metallic behavior for systems that are experimentally observed to be insulators or semiconductors. This failure stems from the inherent difficulty in describing static correlation effects, where multiple electronic configurations contribute significantly to the ground state. The delocalization tendency of conventional functionals presents a critical limitation for drug development researchers studying transition metal-containing enzymes or investigating charge transfer processes in photopharmaceuticals, where accurate prediction of electronic structure is prerequisite for understanding mechanism.

Limitations of DFT+U and Hybrid Functional Approaches

Two predominant strategies have emerged to address these limitations:

DFT+U Approach: This method introduces an effective on-site Coulomb interaction parameter (U) to localize electrons and correct the self-interaction error for specific orbitals [10]. While DFT+U can improve descriptions of localized states, it introduces empirical parameters whose determination often requires experimental calibration, limiting its predictive power. The approach has shown promise in systems like EuB₆ when combined with meta-GGA functionals exhibiting reduced SIE [11].

Hybrid Functionals: These methods incorporate a fraction of exact Hartree-Fock exchange with DFT exchange-correlation, partially mitigating the self-interaction error [10]. While offering improved accuracy for many molecular systems, hybrid functionals face significant challenges for strongly correlated solids, where the appropriate mixing parameter is difficult to determine a priori and computational cost increases substantially.

Table 1: Comparison of Standard DFT Approaches for Strongly Correlated Systems

| Method | Key Principle | Advantages | Limitations for Strongly Correlated Systems |

|---|---|---|---|

| LDA/GGA | Local density approximation/generalized gradient approximation | Computational efficiency; Good for weakly correlated systems | Severe self-interaction error; Underestimates band gaps; Favors metallic states |

| DFT+U | Adds Hubbard U parameter to localize electrons | Corrects delocalization error for specific orbitals; Improved band gaps | U parameter often empirical; Requires experimental calibration; Not fully first-principles |

| Hybrid Functionals | Mixes Hartree-Fock exchange with DFT exchange-correlation | Reduces self-interaction error; Improved molecular properties | High computational cost; Optimal mixing parameter difficult to determine for solids |

Advanced Methodologies Beyond Conventional DFT

Embedding Approaches: Combining DFT with Many-Body Theories

Sophisticated embedding methodologies have emerged that combine the computational efficiency of DFT with accurate many-body theories for treating strongly correlated subspaces:

DFT+DMFT (Dynamical Mean Field Theory): This approach maps the bulk quantum many-body problem onto an impurity model coupled to a self-consistent bath, capturing local temporal fluctuations absent in conventional DFT [10]. DFT+DMFT successfully describes aspects of the electronic structure of correlated materials, but challenges remain in capturing non-local spin fluctuations and vertex corrections beyond the random phase approximation.

Tensor Network Methods: Recent breakthroughs have demonstrated the powerful combination of DFT with tensor networks, particularly for one-dimensional and quasi-one-dimensional materials [10] [12]. This approach uses DFT with the constrained random phase approximation (cRPA) to construct an effective multi-band Hubbard model, which is then solved using matrix product states (MPS). The method provides systematic control over accuracy through the bond dimension and scales efficiently with system size, enabling quantitative prediction of band gaps, spin magnetization, and excitation energies.

The Strong-Interaction Limit of DFT

The strictly correlated electrons (SCE) functional represents the strong-interaction limit of DFT and provides a formally exact approach for addressing strong correlation [13]. This framework reformulates DFT as an optimal transport problem with Coulomb cost, offering insights into the exact form of the exchange-correlation functional in the strong-correlation regime. Integration of the SCE approach into the Kohn-Sham framework (KS-SCE) has shown promising results, such as correctly dissociating Hâ‚‚ molecules where standard approximations fail [13].

Table 2: Advanced Computational Methods for Strongly Correlated Systems

| Method | Theoretical Foundation | System Dimensionality | Key Observables | Computational Scaling |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DFT+DMFT | Dynamical mean field theory; Quantum impurity models | 3D bulk systems | Spectral functions; Metal-insulator transitions | O(N³) to O(Nâ´) with high prefactor |

| Tensor Networks (MPS) | Matrix product states; Renormalization group | 1D and quasi-1D systems | Band gaps; Spin magnetization; Excitation energies | Efficient with system size; Tunable via bond dimension |

| SCE-DFT | Strictly correlated electrons; Optimal transport theory | Molecular systems | Strong-interaction limit; Dissociation curves | Varies with implementation |

Research Toolkit for Strongly Correlated Systems

Essential Computational Reagents and Methodologies

Researchers investigating strongly correlated materials require specialized computational tools to overcome DFT limitations:

cRPA (Constrained Random Phase Approximation): A downfolding technique for constructing effective low-energy models by integrating out high-energy degrees of freedom while calculating screened interaction parameters [10] [12].

Multi-band Hubbard Models: Effective Hamiltonians containing essential physics of correlated materials, with parameters derived from first-principles calculations [10].

Tensor Network Solvers: Mathematical engines based on matrix product states (MPS) and projected entangled-pair states (PEPS) that efficiently represent quantum many-body wavefunctions [10].

Advanced Exchange-Correlation Functionals: Meta-GGAs and double-hybrid functionals with reduced self-interaction error for improved treatment of correlated materials [11].

Experimental Validation Protocols

Accurate assessment of computational methodologies requires comparison with experimental observables:

Band Gap Measurements: Direct comparison between computed and experimentally determined band gaps provides a crucial validation metric [10] [12].

Angle-Resolved Photoemission Spectroscopy (ARPES): Directly probes electronic band structure and many-body effects such as spin-charge separation [10].

X-ray Absorption Near Edge Structure (XANES): Provides element-specific information about electronic states and local symmetry, as employed in EuB₆ studies under pressure [11].

Workflow for Advanced Strong Correlation Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the integrated computational workflow for treating strongly correlated materials, combining first-principles calculations with many-body theories:

Computational Workflow for Correlated Materials

This workflow demonstrates the multi-scale approach required for quantitative descriptions of strongly correlated materials, beginning with conventional DFT calculations and progressing through model construction to advanced many-body solutions.

The limitations of standard DFT for strongly correlated electrons represent a fundamental challenge at the heart of computational quantum chemistry and materials science. While conventional DFT approaches provide an essential starting point with favorable computational scaling, their failures in predicting electronic properties of correlated materials necessitate advanced methodologies that explicitly treat many-body effects. The integration of DFT with many-body theories such as tensor networks, dynamical mean field theory, and the strictly correlated electrons framework represents the frontier of computational research for strongly correlated systems.

For researchers in drug development and chemical design, these advances offer potential pathways to accurate simulation of transition metal catalysts, photopharmaceutical mechanisms, and electronic processes in complex molecular systems. The ongoing development of systematically improvable, computationally efficient methods that bridge quantum and classical scaling paradigms will continue to enhance our fundamental understanding and predictive capabilities for the most challenging strongly correlated materials.

The claim of discovering a room-temperature superconductor, LK-99, sent shockwaves through the scientific community in 2023. This material, a copper-doped lead-oxyapatite (Pb({9})CuP({6})O(_{25})), was purported to exhibit superconductivity at temperatures as high as 400 K (127 °C) under ambient pressure [14]. Such a discovery promised to revolutionize technologies from energy transmission to quantum computing. However, the subsequent global effort to replicate these results unveiled a more sobering reality: profound gaps in our fundamental knowledge and methodologies, particularly in the interplay between classical computational prediction and experimental validation in materials science. This case study examines the LK-99 saga, comparing the performance of theoretical and experimental "protocols" and framing the findings within the broader thesis of quantum versus classical computational scaling in chemistry research.

Experimental Replication: A Consensus of Negative Results

Despite initial global excitement, the consensus that emerged from numerous independent replication attempts was that LK-99 is not a room-temperature superconductor [14]. The following table summarizes key experimental results from peer-reviewed studies and reputable replication efforts, which collectively failed to observe the definitive signatures of superconductivity.

Table 1: Summary of Key Experimental Replication Attempts on LK-99

| Research Group / Study | Synthesis & Methodology Highlights | Key Experimental Results | Conclusion on Superconductivity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cho et al. (2024) [15] | Synthesized LK-99 under various cooling conditions; used Powder X-ray Diffraction (PXRD) for phase analysis. | Slow cooling increased LK-99 phase but also retained impurities. No Meissner effect observed at ambient temperature or in liquid nitrogen. High electrical resistance. | Absence of superconductivity confirmed. Magnetic responses attributed to ferromagnetic impurities. |

| K. Kumar et al. (2023) [16] | Synthesized sample at 925°C; standard protocol from original preprints. | No large-area superconductivity observed at room temperature. No magnetic levitation (Meissner effect) detected. | No evidence of superconductivity in the synthesized sample. |

| PMC Study (2023) [17] | Used high-purity precursors; rigorous phase verification via PXRD and Rietveld refinement. Four-probe resistivity measurement. | Sample was highly resistive, showing insulator-like behavior from 215 to 325 K. Magnetization measurements indicated diamagnetism, not superconductivity. | Confirmed absence of superconductivity in phase-pure LK-99. |

| Beijing University Study [16] | Reproduced the synthesis process precisely. | Synthesized material placed on a magnet produced no repulsion and no magnetic levitation was observed. | No support for the room-temperature superconductor claim. |

| Leslie Schoop (Princeton) [18] | Simple replication attempt; visual and basic property checks. | Resulting crystals were transparent, unlike the opaque material in original claims, indicating different composition/impurities. | LK-99 is not a superconductor. |

| (2S)-2,6-Diamino-2-methylhexanoic acid | (2S)-2,6-Diamino-2-methylhexanoic Acid | Bench Chemicals | |

| 10-Acetoxy-8,9-epoxythymol isobutyrate | 10-Acetoxy-8,9-epoxythymol isobutyrate|High-Quality Reference Standard | 10-Acetoxy-8,9-epoxythymol isobutyrate (CAS 106009-86-3) is for research applications such as antimicrobial and cytotoxicity studies. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

The most definitive experiments measured the material's electrical transport properties, consistently finding that LK-99 is a highly resistive insulator, not a zero-resistance superconductor [17]. The occasional observations of partial magnetic levitation, initially misinterpreted as the Meissner effect, were later attributed to ferromagnetic or diamagnetic impurities like copper(I) sulfide (Cu(_{2})S) that form during the synthesis [14] [19].

The Computational Divide: Classical Predictions vs. Quantum Reality

The LK-99 episode highlighted a critical vulnerability in modern materials research: the over-reliance on and potential misinterpretation of classical computational methods.

The Role of Density Functional Theory (DFT) and Its Shortcomings

Classical computational methods, particularly Density Functional Theory (DFT), were rapidly deployed to assess LK-99's viability. Shortly after the initial claim, a study from Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory used DFT to analyze LK-99 and suggested its structure might host isolated flat bands that could contribute to superconductivity [16] [14]. This theoretical finding was initially seized upon as validation.

However, this optimism exposed a key limitation. DFT, while powerful, operates within the framework of classical computing and has significant shortcomings when modeling complex quantum systems. As solid-state chemist Professor Leslie Schoop pointed out, a major flaw was that these early DFT calculations assumed the crystal structure proposed in the original, unverified preprint [18]. The adage "garbage in, garbage out" applies; an incorrect initial structure guarantees an incorrect electronic structure prediction. Furthermore, standard DFT methods often struggle with strongly correlated electron systems, precisely the kind of physics that might underpin high-temperature superconductivity.

The Quantum Computing Promise

This is where the potential of quantum computing becomes apparent. Unlike classical computers that use bits (0 or 1), quantum computers use qubits, which can exist in superpositions of 0 and 1 simultaneously [20]. This property of "massive quantum parallelism" allows them to naturally simulate quantum mechanical systems [21].

For a problem like predicting a new superconductor, a fault-tolerant quantum computer could, in theory, directly and accurately simulate the many-body quantum interactions within a material's crystal structure. This would circumvent the approximations required by DFT and provide a more reliable prediction of properties like superconductivity before costly and time-consuming experimental synthesis is undertaken. The scaling is fundamentally different: while classical computing power for such simulations grows linearly or polynomially with system complexity, effectively managed quantum computational power could grow exponentially for these specific tasks [20] [22].

Table 2: Classical vs. Quantum Computing in Materials Simulation

| Feature | Classical Computing (e.g., DFT) | Quantum Computing (Potential) |

|---|---|---|

| Basic Unit | Bit (0 or 1) | Qubit (0, 1, or both) |

| Underlying Principle | Binary Logic | Quantum Mechanics (Superposition, Entanglement) |

| Approach to Electron Correlation | Uses approximate functionals; can fail with strong correlations | Naturally handles entanglement and superposition |

| Scaling for Quantum Simulations | Polynomial to exponential, leading to intractable calculations | Theoretically polynomial for exact simulation |

| Maturity for Materials Science | Mature, widely used, but with known limitations | Emerging; requires fault-tolerant hardware not yet available |

| Outcome in LK-99 Case | Provided conflicting and ultimately misleading signals | Could have provided a more definitive theoretical assessment |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Methods for LK-99 Research

The synthesis and analysis of LK-99 require specific precursors and sophisticated instrumentation. The following table details the key research reagents and their functions in the typical experimental protocol.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for LK-99 Synthesis and Analysis

| Reagent / Material | Function in the Experiment | Key Characteristics & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Lead(II) Oxide (PbO) | Precursor for synthesizing Lanarkite (Pbâ‚‚SOâ‚…). | High-purity powder is essential to minimize impurities. |

| Lead(II) Sulfate (PbSOâ‚„) | Co-precursor for synthesizing Lanarkite (Pbâ‚‚SOâ‚…). | Freshly prepared and dried to ensure phase purity [17]. |

| Copper (Cu) Powder | Precursor for synthesizing Copper(I) Phosphide (Cu₃P). | High purity (e.g., 99.999%); checked for absence of CuO [17]. |

| Phosphorus (P) Grains | Precursor for synthesizing Copper(I) Phosphide (Cu₃P). | Handling in inert atmosphere (e.g., Argon glovebox) is critical due to reactivity [15]. |

| Copper(I) Phosphide (Cu₃P) | Final precursor reacted with Lanarkite to produce LK-99. | Phase purity is crucial; unreacted copper can lead to impurities [17]. |

| Lanarkite (Pb₂SO₅) | Final precursor mixed with Cu₃P to produce LK-99. | Synthesized by heating PbO and PbSO₄ at 725°C for 24 hours [14]. |

| Quartz Tube/Ampoule | Reaction vessel for synthesis steps. | Must withstand high temperatures (up to 925°C) and vacuum (10â»Â² to 10â»âµ Torr) [15] [17]. |

| Powder X-ray Diffractometer (PXRD) | Primary tool for verifying the crystal structure and phase purity of all precursors and the final product. | Data is analyzed with Rietveld refinement software (e.g., FullProf) for quantitative phase analysis [15] [17]. |

| Physical Property Measurement System (PPMS) | Measures electrical transport properties (e.g., resistivity) under varying temperatures and magnetic fields. | Used in a four-probe configuration to accurately measure the resistance of the sample [17]. |

| SQUID Magnetometer | Measures the magnetic properties of a material with high sensitivity. | Used to detect diamagnetism and check for the Meissner effect, a hallmark of superconductivity [17]. |

| 1-Cyanoethyl(diethylamino)dimethylsilane | 1-Cyanoethyl(diethylamino)dimethylsilane | 1-Cyanoethyl(diethylamino)dimethylsilane is a silane reagent for surface modification, polymer synthesis, and thin film deposition. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

| 3-Iodo-N-[(benzyloxy)carbonyl]-L-tyrosine | 3-Iodo-N-[(benzyloxy)carbonyl]-L-tyrosine, CAS:79677-62-6, MF:C17H16INO5, MW:441.22 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Synthesizing and Testing LK-99

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive multi-step workflow for synthesizing and characterizing LK-99, integrating the reagents and methods from the toolkit.

Diagram Title: LK-99 Synthesis and Characterization Workflow

Synthesis Protocol:

Precursor Preparation:

- Synthesis of Lanarkite (Pb₂SO₅): Mix lead(II) oxide (PbO) and lead(II) sulfate (PbSO₄) powders in a 1:1 molar ratio. Pelletize the mixture and heat it in an alumina crucible at 725 °C for 24 hours [17]. The product is a white solid.

- Synthesis of Copper(I) Phosphide (Cu₃P): In an argon-filled glovebox to prevent oxidation, uniformly grind together copper powder and phosphorus grains in a 3:1 molar ratio [15]. Pelletize the mixture, seal it in an evacuated (10â»Â² to 10â»âµ Torr) quartz tube, and heat it at 550 °C for 48 hours [14] [17].

Final LK-99 Synthesis: Thoroughly grind the synthesized Lanarkite and Copper(I) Phosphide crystals together in a stoichiometric ratio. Pelletize the mixed powder, seal it in an evacuated quartz tube, and react it at a high temperature of 925 °C for 5 to 20 hours [15] [14]. The resulting product is a gray-black, polycrystalline solid.

Characterization Protocol:

- Structural Analysis (PXRD): Crush the final product into a fine powder and analyze it using Powder X-ray Diffraction (PXRD). The data should be refined using the Rietveld method (e.g., with FullProf software) to confirm the formation of the lead-apatite crystal structure and quantify the presence of any impurity phases, such as Cuâ‚‚S [15] [17].

- Electrical Transport Measurement: Use a four-probe resistivity measurement setup within a Physical Property Measurement System (PPMS). This method eliminates the contribution of contact resistance, allowing for accurate measurement of the sample's intrinsic resistance as a function of temperature (e.g., from 215 K to 325 K) [17].

- Magnetic Property Measurement: Use a SQUID (Superconducting Quantum Interference Device) magnetometer to measure the sample's magnetization with high sensitivity. This test looks for the definitive Meissner effect (perfect diamagnetism) and measures the magnetic susceptibility [17].

- Magnetic Levitation Test: Visually test small sample fragments by placing them on a permanent magnet (e.g., Ndâ‚‚Feâ‚â‚„B) at room temperature. A true superconductor would demonstrate stable levitation and flux pinning, not just a partial tilt due to ferromagnetism [16] [14].

The LK-99 story is not a tale of failure but a powerful case study in the scientific process. It underscores a critical gap in our current research paradigm: the limitations of classical computational methods in predicting and explaining complex quantum phenomena in materials. While DFT is an invaluable tool, its misapplication in the absence of robust experimental structures can lead the community down unproductive paths.

The path forward requires a more integrated and humble approach. Experimental synthesis must be performed with scrupulous attention to detail and phase purity, and theoretical predictions must be treated as guides rather than gospel. Ultimately, bridging this fundamental knowledge gap may hinge on the next computational revolution: the advent of practical quantum computing. By providing a native platform for simulating quantum matter, quantum computers could one day transform the search for revolutionary materials like room-temperature superconductors from a process of serendipitous discovery into one of principled design.

Molecular systems are, at their fundamental level, governed by the laws of quantum mechanics. The behavior of electrons and atomic nuclei involves quantum phenomena such as superposition, entanglement, and tunneling—effects that classical computers can simulate only with exponential resource growth. This inherent quantum nature makes molecular systems a putative native application for quantum processors (QPUs), which operate on the same physical principles [23] [24]. For computational chemistry, this suggests the potential for a profound advantage: quantum computers could simulate molecular processes with natural efficiency, potentially bypassing the steep approximations and computational costs that challenge even the most powerful classical supercomputers [25] [26].

The central challenge in classical computational chemistry is the exponential scaling of exact methods like Full Configuration Interaction (FCI) with system size. While approximate methods like Density Functional Theory (DFT) or Coupled Cluster offer more favorable scaling, they can fail for systems with strong electron correlation, such as transition metal catalysts or complex biomolecules [25] [26]. Quantum algorithms, particularly Quantum Phase Estimation (QPE), offer a promising alternative with the potential for polynomial scaling for these problems [26]. This guide provides an objective comparison of the current performance landscape between classical and quantum computational chemistry approaches, detailing the experimental protocols and hardware requirements that underpin recent advancements.

Computational Scaling: A Theoretical and Practical Comparison

The theoretical advantage of quantum computing in chemistry stems from the different ways classical and quantum algorithms scale with problem size, typically measured by the number of basis functions (N). The table below summarizes the expected timelines for quantum algorithms to surpass various classical methods for a representative high-accuracy target.

Table 1: Projected timelines for quantum phase estimation (QPE) to surpass classical computational chemistry methods for a representative high-accuracy target (error < 1mHa). Adapted from [26].

| Computational Method | Classical Time Complexity | Projected Year for QPE Surpassment |

|---|---|---|

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | O(N³) | Beyond 2050 |

| Hartree-Fock (HF) | O(Nâ´) | Beyond 2050 |

| Møller-Plesset Second Order (MP2) | O(Nâµ) | Beyond 2050 |

| Coupled Cluster Singles & Doubles (CCSD) | O(Nâ¶) | ~2044 |

| CCSD with Perturbative Triples (CCSD(T)) | O(Nâ·) | ~2036 |

| Full Configuration Interaction (FCI) | O*(4^N) | ~2031 |

This analysis suggests that quantum computing will first disrupt the most accurate, classically intractable methods before competing with faster, less accurate approximations [26]. The polynomial scaling of QPE (O(N²/ϵ) for a target error ϵ) is expected to eventually overtake the exponential scaling of FCI and the high-order polynomial scaling of "gold standard" methods like CCSD(T). However, for the foreseeable future, low-accuracy methods like DFT will remain solidly in the classical computing domain [26].

Experimental Protocols in Hybrid Quantum-Classical Chemistry

Current quantum hardware, termed Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ), is not yet capable of running long, fault-tolerant algorithms like QPE. Therefore, today's experimental focus is on hybrid quantum-classical algorithms that delegate the most quantum-native subproblems to the QPU while leveraging classical high-performance computing (HPC) for the rest [27] [9] [28].

The Quantum-Centric Supercomputing Approach (Caltech/IBM/RIKEN)

A leading protocol demonstrated in 2025 for studying the [4Fe-4S] molecular cluster—a complex iron-sulfur system relevant to nitrogen fixation—showcases this hybrid paradigm [27].

Objective: To determine the ground-state energy of the [4Fe-4S] cluster by solving the electronic Schrödinger equation. Classical Challenge: The Hamiltonian matrix for this system is too large to handle exactly. Classical heuristics prune this matrix, but their approximations can be unreliable [27]. Quantum Role: An IBM Heron quantum processor (using up to 77 qubits) was used to rigorously identify the most important components of the Hamiltonian matrix, replacing classical heuristics [27]. Workflow: The quantum computer processed the full problem to output a compressed, relevant subset of the Hamiltonian. This reduced matrix was then passed to the Fugaku supercomputer for final diagonalization to obtain the exact wave function and energy [27].

This "quantum-centric supercomputing" approach demonstrates a practical division of labor, using the QPU as a specialized accelerator for the most quantum-native task: identifying the essential structure of a complex quantum state [27].

The DMET-SQD Approach (Cleveland Clinic/IBM/Michigan State)

Another advanced protocol, the Density Matrix Embedding Theory with Sample-Based Quantum Diagonalization (DMET-SQD), was used to simulate molecular conformers of cyclohexane, a standard test in organic chemistry [28].

Objective: To compute the relative energies of different cyclohexane conformers with chemical accuracy (within 1 kcal/mol). Classical Challenge: Simulating entire large molecules exactly is infeasible; mean-field approximations ignore crucial electron correlations [28]. Quantum Role: The DMET method breaks the molecule into smaller fragments. The SQD algorithm, run on an IBM Eagle processor (using 27-32 qubits), simulated the quantum chemistry of these individual fragments. SQD is notably tolerant of the noise present in current-generation hardware [28]. Workflow: The global molecule is partitioned into fragments. A classical computer handles the bulk environment, while the quantum computer solves the embedded fragment problem via SQD. The results are integrated back classically to reconstruct the total energy [28]. Result: The hybrid DMET-SQD method achieved energy differences within 1 kcal/mol of classical benchmarks, validating its potential for biologically relevant molecules [28].

The following diagram visualizes the logical flow common to these hybrid computational workflows.

The Researcher's Toolkit for Hybrid Quantum Chemistry

Implementing the protocols above requires a suite of specialized hardware and software "reagents." The following table details the key components.

Table 2: Essential "Research Reagent Solutions" for current hybrid quantum-classical computational chemistry experiments.

| Tool Category | Specific Example | Function & Relevance |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Hardware (QPU) | IBM Heron/Eagle Processors [27] [28] | Superconducting qubit processors that perform the core quantum computations; require milli-Kelvin cooling. |

| Classical HPC | Fugaku Supercomputer [27] | A world-class supercomputer that handles the computationally intensive classical portions of the hybrid algorithm. |

| Software Libraries | Qiskit [28] | An open-source SDK for working with quantum computers at the level of circuits, pulses, and algorithms. |

| Software Libraries | Tangelo [28] | An open-source quantum chemistry toolkit used to implement the DMET embedding framework. |

| Algorithmic Framework | Density Matrix Embedding Theory (DMET) [28] | A fragmentation technique that divides a large molecular problem into smaller, quantum-tractable fragments. |

| Algorithmic Framework | Sample-Based Quantum Diagonalization (SQD) [28] | A noise-resilient quantum algorithm used to solve for the energy of a quantum fragment on NISQ hardware. |

| Error Mitigation | Gate Twirling & Dynamical Decoupling [28] | Software-level techniques applied to quantum circuits to mitigate the effect of noise without full error correction. |

| Purine, 2,6-diamino-, sulfate, hydrate | Purine, 2,6-diamino-, sulfate, hydrate, CAS:116295-72-8, MF:C10H16N12O5S, MW:416.38 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 2-(2-Amino-4-methoxyphenyl)acetonitrile | 2-(2-Amino-4-methoxyphenyl)acetonitrile | RUO | 2-(2-Amino-4-methoxyphenyl)acetonitrile, a key intermediate for heterocyclic synthesis. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

Discussion and Future Horizons

The experimental data and protocols demonstrate that hybrid quantum-classical approaches are already yielding chemically meaningful results for small to medium-sized systems [27] [28]. The primary advantage of the QPU in these workflows is its ability to handle the strong electron correlations and exponential state spaces that challenge even the most powerful classical HPCs for certain problems [25] [26].

However, the path to a unambiguous "quantum advantage" in chemistry is still long. Current methods require heavy error mitigation and are limited by the number of reliable logical qubits. Experts estimate that robust fault-tolerant quantum computers capable of outperforming classical computers for high-accuracy problems like CCSD(T) or FCI are likely 10-20 years away [25] [26]. The field is actively pursuing a co-design strategy, where chemists, algorithm developers, and hardware engineers collaborate to identify the problems and refine the tools that will define the next decade of progress [9].

For researchers in drug development and materials science, the present utility of quantum computing lies in its role as a specialized accelerator within a larger HPC ecosystem. As hardware matures, its impact is projected to grow from highly accurate small-molecule simulations toward larger, more complex systems like enzymes and novel materials, fundamentally reshaping the landscape of computational discovery [25] [26] [9].

Quantum Algorithms in Action: From Theory to Real-World Chemistry Problems

In the field of computational chemistry and drug discovery, researchers face a fundamental challenge: the accurate simulation of molecular systems requires solving the Schrödinger equation, a task whose computational cost grows exponentially with system size on classical computers. Methods like Density Functional Theory (DFT) scale as ( \mathcal{O}(N^3) ), while more accurate approaches such as Coupled Cluster theory scale as steeply as ( \mathcal{O}(N^7) ), where ( N ) represents the number of electrons in the system [29]. This exponential scaling creates an insurmountable barrier for studying complex molecules relevant to pharmaceutical development, such as iron-sulfur clusters in enzymes or covalent drug-target interactions.

Quantum computing offers a potential pathway to overcome this bottleneck, as quantum systems can naturally simulate other quantum systems. However, current Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) hardware remains limited by qubit counts, connectivity constraints, and inherent noise. Hybrid Quantum-Classical (HQC) models have emerged as a strategic compromise, leveraging classical computers for the bulk of computational workload while delegating specific, quantum-native subroutines to quantum processors. This architecture creates a practical bridge to quantum advantage, enabling researchers to explore quantum algorithms on today's hardware while addressing real-world chemical problems [4] [29] [30].

Hybrid Model Architectures for Chemical Simulation

The Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) Framework

The Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) has become the cornerstone algorithm for quantum chemistry on NISQ devices. This hybrid approach combines a parameterized quantum circuit (PQC) with classical optimization to compute molecular properties, most commonly the ground state energy [30]. The quantum processor's role is to prepare and measure the quantum state of the molecular system, while the classical processor adjusts the circuit parameters to minimize the energy expectation value.

The VQE workflow follows these steps:

- Problem Mapping: The molecular Hamiltonian is transformed from fermionic to qubit representation using techniques like Jordan-Wigner or parity transformation.

- Ansatz Preparation: A parameterized quantum circuit (ansatz) is selected to prepare trial wavefunctions.

- Measurement and Optimization: The energy expectation value is measured on the quantum device, and a classical optimizer adjusts circuit parameters to minimize this energy.

This framework has been successfully applied to molecular systems of real-world relevance, including the study of prodrug activation mechanisms and covalent inhibitor interactions [30].

Quantum-Centric Supercomputing

A more recent architecture, termed "quantum-centric supercomputing," demonstrates how quantum and classical resources can be integrated at scale. In this approach, a quantum processor identifies the most critical components of large Hamiltonian matrices, which are then solved exactly on classical supercomputers. This division of labor was showcased in a landmark study where researchers used an IBM Heron quantum processor with up to 77 qubits to simplify the mathematics for an iron-sulfur molecular cluster, then leveraged the Fugaku supercomputer to solve the problem [4].

This methodology addresses a key bottleneck in quantum chemistry: classical algorithms often rely on approximations to prune down exponentially large Hamiltonian matrices. The quantum computer provides a more rigorous selection of relevant matrix components, potentially improving accuracy while reducing computational overhead [4].

Table: Hybrid Quantum-Classical Architectures for Chemical Simulation

| Architecture | Quantum Component Role | Classical Component Role | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| VQE [30] | State preparation and energy measurement | Parameter optimization and error mitigation | Molecular energy calculations, reaction profiling |

| Quantum-Centric Supercomputing [4] | Hamiltonian simplification and component selection | Large-scale matrix diagonalization | Complex molecular clusters, active space selection |

| Hybrid ML Potentials [29] | Feature embedding and non-linear transformation | Message passing and structural representation | Materials simulation, molecular dynamics |

Performance Comparison: Quantum-Classical Models vs. Classical Baselines

Chemical Accuracy in Molecular Simulations

Recent studies have provided quantitative comparisons between hybrid quantum-classical approaches and classical computational methods. In drug discovery applications, researchers have demonstrated that HQC models can achieve chemical accuracy while potentially reducing computational resource requirements for specific problem classes.

In one investigation focusing on prodrug activation—a critical process in pharmaceutical design—researchers computed Gibbs free energy profiles for carbon-carbon bond cleavage in β-lapachone derivatives. The hybrid quantum-classical pipeline employed a hardware-efficient ( R_y ) ansatz with a single layer as the parameterized quantum circuit for VQE. The results showed that the quantum computation agreed with Complete Active Space Configuration Interaction (CASCI) calculations, which serve as the reference exact solution within the active space approximation [30].

Table: Performance Comparison for Prodrug Activation Study [30]

| Computational Method | System Size (Qubits) | Accuracy vs. CASCI | Key Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classical DFT (M06-2X) | N/A | Reaction barrier consistent with experiment | C-C bond cleavage in β-lapachone |

| Classical CASCI | N/A | Reference method | Active space approximation |

| Hybrid VQE (R𑦠ansatz) | 2 | Consistent with CASCI | Quantum computation of reaction barrier |

Resource Efficiency and Scalability

Beyond accuracy metrics, hybrid models demonstrate advantages in resource efficiency. The application of HQC models to machine learning potentials (MLPs) for materials science reveals that replacing classical neural network components with variational quantum circuits can maintain accuracy while potentially reducing parameter counts. In benchmarks for liquid silicon simulations, hybrid quantum-classical MLPs achieved accurate reproduction of high-temperature structural and thermodynamic properties, matching classical state-of-the-art equivariant message-passing neural networks [29].

This efficiency stems from the ability of quantum circuits to generate highly complex non-linear transformations with relatively few parameters. The quantum processor executes targeted sub-tasks that supply additional expressivity, while the classical processor handles the bulk of computation [29]. This division of labor is particularly advantageous for NISQ devices, which remain constrained by qubit coherence times and gate fidelities.

Experimental Protocols for Hybrid Quantum-Classical Chemistry

Protocol 1: Quantum Computation of Reaction Profiles

The determination of Gibbs free energy profiles for chemical reactions represents a cornerstone application of quantum chemistry in drug discovery. The following protocol outlines the hybrid approach used to study covalent bond cleavage in prodrug activation [30]:

System Preparation:

- Select key molecules along the reaction coordinate

- Perform conformational optimization using classical methods

- Define active space (typically 2 electrons in 2 orbitals for C-C bond cleavage)

Hamiltonian Generation:

- Generate molecular Hamiltonian in fermionic form

- Apply parity transformation to convert to qubit representation

- Utilize the 6-311G(d,p) basis set for consistent comparison

Quantum Circuit Configuration:

- Implement hardware-efficient ( R_y ) ansatz with single layer

- Apply readout error mitigation techniques

- Execute on superconducting quantum processor (2 qubits)

Classical-VQE Integration:

- Use classical optimizer to minimize energy expectation value

- Employ polarizable continuum model (PCM) for solvation effects

- Calculate single-point energies with solvent corrections

Validation:

- Compare quantum results with classical CASCI and HF calculations

- Benchmark against experimental reaction feasibility

This protocol successfully demonstrated the computation of energy barriers for C-C bond cleavage, a crucial parameter in prodrug design that determines whether reactions proceed spontaneously under physiological conditions [30].

Protocol 2: Quantum-Centric Supercomputing for Complex Molecules

The study of the [4Fe-4S] molecular cluster—an important component in biological systems like the enzyme nitrogenase—required a more sophisticated protocol leveraging both quantum and classical resources at scale [4]:

Problem Decomposition:

- Define the full molecular system with all electrons and atomic positions

- Generate the complete Hamiltonian matrix

Quantum Pre-processing:

- Utilize IBM quantum device (Heron processor) with up to 77 qubits

- Identify the most important components in the Hamiltonian matrix

- Prune less relevant matrix elements using quantum measurements

Classical Post-processing:

- Feed the simplified Hamiltonian to Fugaku supercomputer

- Perform exact diagonalization on the reduced matrix

- Solve for the system's wave function and ground state energy

Validation and Analysis:

- Compare results with classical heuristic approaches

- Assess computational efficiency and accuracy gains

This protocol demonstrated that quantum computers can rigorously select relevant Hamiltonian components, potentially replacing the classical heuristics traditionally used for this task [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Implementing hybrid quantum-classical models requires specialized tools and frameworks that bridge the quantum-classical divide. The following table outlines key "research reagents" essential for conducting experiments in this domain:

Table: Essential Research Reagents for Hybrid Quantum-Classical Chemistry

| Tool/Platform | Type | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| TenCirChem [30] | Software Package | Quantum computational chemistry | VQE implementation for drug discovery |

| PyTorch/PennyLane [31] | Machine Learning Library | Hybrid model development | Physics-informed neural networks |

| OpenQASM [32] | Quantum Assembly Language | Quantum circuit representation | Benchmarking quantum algorithms |

| Hardware-Efficient Ansatz [30] | Quantum Circuit | State preparation | R𑦠ansatz for molecular simulations |

| RIKEN Fugaku [4] | Classical Supercomputer | Large-scale matrix diagonalization | Quantum-centric supercomputing |

| IBM Heron Processor [4] | Quantum Hardware | Quantum computation | 77-qubit chemical simulations |

| Oxacyclohexadec-12-en-2-one, (12E)- | Oxacyclohexadec-12-en-2-one, (12E)-, CAS:111879-80-2, MF:C15H26O2, MW:238.37 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| 4-Decyltetradecan-1-ol | 4-Decyltetradecan-1-ol | High-Purity Long-Chain Fatty Alcohol | 4-Decyltetradecan-1-ol, a high-purity C24 fatty alcohol for research on lipids & surfactants. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

Hybrid quantum-classical models represent a pragmatic and powerful bridge to quantum computational advantage in chemistry and drug discovery. Current evidence demonstrates that these models can already tackle real-world problems, from prodrug activation kinetics to complex molecular cluster simulations, with accuracy comparable to classical methods [4] [30]. While definitive quantum advantage across all chemical applications remains on the horizon, the architectural patterns established by HQC models provide a clear pathway forward.

The strategic division of labor—where quantum processors handle naturally quantum subroutines while classical computers manage optimization, error mitigation, and large-scale data processing—enables researchers to extract maximum value from current NISQ devices. As quantum hardware continues to improve in scale and fidelity, the balance within these hybrid architectures will likely shift toward greater quantum responsibility, potentially unlocking the exponential scaling advantages promised by quantum mechanics for molecular simulation.

Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) for Calculating Molecular Ground-State Energy

The calculation of molecular ground-state energies is a fundamental challenge in chemistry and drug discovery. Classical computational methods, such as density functional theory (DFT) and post-Hartree-Fock approaches, provide valuable insights but often fall short when applied to large systems and strongly correlated electrons, or when high accuracy is required [33]. The complexity of solving the electronic Schrödinger equation scales exponentially with system size on classical computers, creating an intractable bottleneck for simulating complex molecules or materials [34].

Quantum computing represents a paradigm shift, leveraging the principles of quantum mechanics to process information in ways that classical computers cannot [33]. The Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) has emerged as a leading hybrid algorithm for the Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) era, offering a potential pathway to overcome classical scaling limitations [35]. This guide provides an objective comparison of VQE performance against classical alternatives, detailing experimental methodologies and presenting quantitative benchmarking data to inform researchers and drug development professionals.

Algorithmic Frameworks and Workflows

The VQE Algorithm: A Hybrid Approach

The Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) is a hybrid quantum-classical algorithm that leverages the variational principle to approximate ground-state energies [35]. Fundamentally, VQE operates by:

- Parameterized Wavefunction: A trial wavefunction (ansatz) is prepared on a quantum processor using a parameterized quantum circuit, ( |\Psi(\boldsymbol{\theta})\rangle \equiv \hat{U}(\boldsymbol{\theta})|\Psi_0\rangle ).

- Expectation Measurement: The quantum computer measures the expectation value of the molecular Hamiltonian, ( E[\Psi(\boldsymbol{\theta})] = \langle \Psi(\boldsymbol{\theta}) | \hat{H} | \Psi(\boldsymbol{\theta}) \rangle ).

- Classical Optimization: A classical optimizer iteratively adjusts parameters ( \boldsymbol{\theta} ) to minimize the energy ( E[\Psi(\boldsymbol{\theta})] ), satisfying the variational principle ( E_g \leq E[\Psi(\boldsymbol{\theta})] ) [35].

This framework is particularly well-suited for NISQ devices because it uses quantum resources primarily for preparing and measuring quantum states, while offloading the optimization workload to classical computers [33].

Quantum-Classical Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow of a VQE calculation within a quantum-DFT embedding framework, as implemented in benchmarking studies [33]:

Advanced VQE Variants

Recent research has developed enhanced VQE variants to address limitations like barren plateaus and high measurement costs:

- ADAPT-VQE: Builds the ansatz iteratively, adding one quantum gate at a time based on the largest gradient. This gradient-driven strategy can bypass barren plateaus but is highly measurement-intensive [36].

- Greedy Gradient-Free Adaptive VQE (GGA-VQE): A "greedy" approach that selects operators and their optimal parameters in a single step. It uses only 2-5 circuit measurements per iteration and demonstrates superior noise resilience, having been successfully demonstrated on a 25-qubit quantum computer [36].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Benchmarking Framework: The BenchQC Protocol

Recent systematic benchmarking studies, such as those using the BenchQC toolkit, have employed rigorous methodologies to evaluate VQE performance [33] [37] [38]:

- Molecular Systems: Focus on small aluminum clusters (Alâ», Alâ‚‚, Al₃â») chosen for intermediate complexity, relevance to materials science, and availability of reliable classical benchmarks from the Computational Chemistry Comparison and Benchmark DataBase (CCCBDB) [33].

- Quantum-DFT Embedding: The system is divided into a classical region (handled by DFT for core electrons) and a quantum region (handled by VQE for strongly correlated valence electrons) [33]. This hybrid approach mitigates current NISQ device limitations.

- Parameter Variation: Systematic testing of key parameters including:

- Classical optimizers (SLSQP, ADAM, BFGS, etc.)

- Circuit types (EfficientSU2, UCCSD, etc.)

- Basis sets (STO-3G, higher-level sets)

- Number of circuit repetitions

- Simulator types (statevector, noisy simulations)

- Reference Calculations: Results are compared against exact diagonalization using NumPy and reference data from CCCBDB to compute percent errors [33].

Classical Reference Methods

For context, VQE performance is typically compared against these classical computational chemistry methods:

- Full Configuration Interaction (FCI): Provides exact solutions within a given basis set but is computationally prohibitive for large systems.

- Coupled Cluster Theory (e.g., CCSD(T)): Considered the "gold standard" for quantum chemistry accuracy but scales steeply (O(Nâ·) for CCSD(T)).

- Density Functional Theory (DFT): More computationally efficient (O(N³)) but can be inaccurate for systems with strong electron correlation.

Performance Comparison and Benchmarking Data

VQE Configuration Performance

Comparative studies reveal how algorithmic choices significantly impact VQE performance. The table below summarizes key findings from benchmarking experiments on molecular systems:

Table 1: Performance of VQE Configurations on Molecular Systems

| Molecular System | Optimal Ansatz | Optimal Optimizer | Key Performance Metrics | Reference Method Error |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Silicon atom [39] | UCCSD (with zero initialization) | ADAM | Most stable and precise results; close approximation to experimental values | N/A |

| Aluminum clusters (Alâ», Alâ‚‚, Al₃â») [33] | EfficientSU2 | SLSQP (among tested) | Percent errors consistently below 0.2% against CCCBDB | CCCBDB benchmarks |

| Hâ‚‚O, LiH [36] | GGA-VQE (adaptive) | Gradient-free greedy | Nearly 2x more accurate than ADAPT-VQE for Hâ‚‚O under noise; ~5x more accurate for LiH | Chemical accuracy threshold |

| 25-spin Ising model [36] | GGA-VQE (adaptive) | Gradient-free greedy | >98% fidelity on 25-qubit hardware; converged computation on NISQ device | Exact diagonalization |

Optimizer Performance Comparison

The choice of classical optimizer significantly impacts convergence efficiency and final energy accuracy:

Table 2: Classical Optimizer Performance in VQE Calculations

| Optimizer | Full Name | Convergence Efficiency | Stability | Computational Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SLSQP [33] | Sequential Least Squares Programming | Efficient convergence in benchmark studies | Stable for small molecules | Moderate |

| ADAM [39] | Adaptive Moment Estimation | Superior for silicon atom with UCCSD | Robust with zero initialization | Moderate |

| L-BFGS-B [40] | Limited-memory BFGS | Fast convergence when stable | Can get stuck in local minima | Low-memory, efficient |

| SPSA [40] | Simultaneous Perturbation Stochastic Approximation | Resilient to noise | Suitable for noisy hardware | Very low (few measurements) |

| AQGD [40] | Alternating Quantum Gradient Descent | Quantum-aware optimization | Moderate | Moderate |

| COBYLA [40] | Constrained Optimization By Linear Approximation | Gradient-free, reasonable convergence | Less efficient for high dimensions | Low |

Ansatz Performance Comparison

The ansatz choice balances expressibility against quantum resource requirements:

Table 3: Quantum Ansatz Comparison for Molecular Simulations

| Ansatz Type | Description | Strengths | Weaknesses | Hardware Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UCCSD [39] | Unitary Coupled Cluster Singles and Doubles | Chemically inspired, high accuracy for silicon atom | Deeper circuits, more gates | Low on current devices |

| EfficientSU2 [33] | Hardware-efficient parameterized circuit | Low-depth, tunable expressiveness | Does not conserve physical symmetries | High for NISQ devices |

| k-UpCCGSD [39] | Unitary Pair Coupled Cluster with Generalized Singles and Doubles | Moderate accuracy with reduced depth | Less accurate than UCCSD | Moderate |

| ParticleConservingU2 [39] | Particle-conserving universal 2-qubit ansatz | Remarkably robust across optimizers | May be less expressive | Moderate |

| GGA-VQE [36] | Greedy gradient-free adaptive ansatz | Noise-resilient, minimal measurements | Less flexible final circuit | Very high (2-5 measurements/iteration) |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Implementing VQE experiments requires both computational and chemical resources. The table below details key "research reagent" solutions for VQE experiments in computational chemistry:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for VQE Experiments

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Role | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantum Software Platforms | Qiskit (v43.1) [33], CUDA-Q [41], InQuanto [41] | Provides interfaces for quantum algorithm implementation, circuit design, and execution | Qiskit Nature's ActiveSpaceTransformer used for orbital selection |

| Classical Computational Chemistry | PySCF [33], NumPy [33] | Performs initial orbital analysis; provides exact diagonalization benchmarks | Integrated within Qiskit framework for seamless workflow |

| Molecular Databases | CCCBDB [33], JARVIS-DFT [33] | Sources of pre-optimized molecular structures and benchmark data | Provides reliable ground-truth data for validation |

| Classical Optimizers | SLSQP, ADAM, L-BFGS-B, SPSA [40] | Adjusts quantum circuit parameters to minimize energy | Choice depends on convergence needs and noise resilience |

| Quantum Ansätze | UCCSD, EfficientSU2, Hardware-efficient [39] | Forms parameterized trial wavefunctions for VQE | Balance between chemical accuracy and NISQ feasibility |

| Error Mitigation Techniques | Zero-noise extrapolation, Probabilistic error cancellation [39] | Reduces impact of hardware noise without full error correction | Essential for obtaining meaningful results on real devices |

| Active Space Tools | ActiveSpaceTransformer (Qiskit Nature) [33] | Selects chemically relevant orbitals for quantum computation | Focuses computational resources on important regions |

| 1(or 2)-(2-Ethylhexyl) trimellitate | 1(or 2)-(2-Ethylhexyl) trimellitate | High-Purity RUO | 1(or 2)-(2-Ethylhexyl) trimellitate, a high-purity plasticizer & solvent for material science research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

| N-(4-methylpyridin-2-yl)acetamide | N-(4-methylpyridin-2-yl)acetamide | Research Chemical | N-(4-methylpyridin-2-yl)acetamide for research applications. This product is For Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

The systematic benchmarking of VQE reveals a nuanced picture of its current capabilities and future potential for calculating molecular ground-state energies. When appropriately configured with optimal ansatzes, optimizers, and initialization strategies, VQE can achieve remarkable accuracy, with percent errors below 0.2% for small aluminum clusters compared to classical benchmarks [33]. The development of noise-resilient variants like GGA-VQE, which has been successfully demonstrated on a 25-qubit quantum computer, represents a significant step toward practical quantum advantage on NISQ devices [36].

However, substantial challenges remain. Quantum noise severely degrades VQE performance, necessitating robust error mitigation strategies [39]. The optimal configuration (ansatz, optimizer, initialization) appears to be system-dependent, requiring careful benchmarking for each new class of molecules [39]. While VQE shows promise for quantum chemistry applications, including drug discovery [34], its scalability to large, complex molecular systems awaits advances in both quantum hardware and algorithm design.

The quantum-classical hybrid approach of VQE, particularly when embedded within DFT frameworks, offers a pragmatic pathway for leveraging current quantum resources while mitigating their limitations. As quantum hardware continues to evolve, VQE and its variants may ultimately fulfill their potential to overcome the fundamental scaling limitations of classical computational chemistry methods.

The simulation of drug-target interactions represents a cornerstone of modern computational chemistry, essential for understanding mechanisms of drug action and designing new therapeutics. This challenge is particularly acute for high-impact targets like the KRAS oncogene, a key driver in pancreatic, colorectal, and lung cancers that has historically been considered "undruggable" due to its smooth surface and picomolar affinity for nucleotides [42] [43]. The central thesis in modern computational chemistry posits that quantum computing algorithms offer fundamentally superior scaling properties for simulating complex biochemical systems compared to classical computational approaches. As drug discovery confronts the vastness of chemical space (~10â¶â° molecules) and the complexity of biological systems, classical computing faces intrinsic limitations in processing power and algorithmic efficiency [44] [45]. This review objectively compares emerging quantum workflows against established classical methods for simulating KRAS inhibition, providing performance data, experimental protocols, and analytical frameworks to guide researchers in selecting appropriate computational strategies.

KRAS Biology and Therapeutic Significance

The Kirsten Rat Sarcoma Viral Oncogene Homolog (KRAS) protein functions as a molecular switch, cycling between active GTP-bound and inactive GDP-bound states to regulate critical cellular signaling pathways including MAPK and PI3K-AKT [42]. Oncogenic mutations, most frequently at codons 12, 13, and 61, impair GTP hydrolysis and lock KRAS in a constitutively active state, driving uncontrolled cell proliferation and survival [43]. KRAS mutations demonstrate distinct tissue-specific prevalence patterns: G12D and G12V dominate in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, G12C in lung adenocarcinoma (particularly among smokers), and A146 mutations primarily in colorectal cancer [42]. This mutational landscape creates a complex therapeutic targeting environment requiring sophisticated computational approaches.

Table 1: Prevalence of Major KRAS Mutations in Human Cancers

| Mutation | Primary Cancer Associations | Approximate Prevalence |

|---|---|---|

| G12D | Pancreatic, Colorectal | ~33% of KRAS mutations |

| G12V | Pancreatic, Colorectal | ~20% of KRAS mutations |

| G12C | Lung | ~45% of NSCLC KRAS mutations |

| G12R | Pancreatic | ~10-15% of PDAC mutations |

| G13D | Colorectal | ~14% of KRAS mutations |

| Q61H | Multiple | ~2% of KRAS mutations |

Classical Computational Approaches: Methodologies and Limitations

Molecular Dynamics and QM/MM Simulations

Classical molecular dynamics (MD) and quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics (QM/MM) simulations have provided crucial insights into KRAS function and inhibition. Yan et al. utilized QM/MM simulations to elucidate the novel mechanism of GTP hydrolysis catalyzed by wild-type KRAS and the KRASG12R mutant [46]. Their methodology involved:

- System Preparation: Crystal structures of WT-KRAS-GTP and KRASG12R-GTP complexes (PDB IDs: 6XI7 and 6CU6) were obtained from the Protein Data Bank [46].

- Molecular Dynamics: Systems were solvated in TIP3P water boxes with NaCl concentration maintained at 0.15 M using AMBER20 package.

- QM/MM Calculations: Employed the ONIOM method with Gaussian 16 and AMBER20, with the QM region treated at the B3LYP/6-31G* level and MM region with the ff14SB forcefield.

- Pathway Analysis: Four distinct GTP hydrolysis mechanisms were computed and compared using potential energy surface scans [46].

This research revealed a novel GTP hydrolysis mechanism assisted by Mg²âº-coordinated water molecules, with energy barriers lower than previously reported pathways (14.8 kcal/mol for Model A and 18.5 kcal/mol for Model B) [46]. The G12R mutation was found to introduce significant steric hindrance at the hydrolysis site, explaining its impaired catalytic rate despite favorable energy barriers [46].

Structure-Based Virtual Screening

Structure-based virtual screening represents another workhorse classical approach. A 2022 study employed pharmacophore modeling, molecular docking, and MD simulations to identify KRAS G12D inhibitors [47]. The experimental protocol comprised:

- Pharmacophore Generation: A ligand-based common feature pharmacophore model was developed from known KRAS G12D inhibitors, featuring two hydrogen bond donors, one hydrogen bond acceptor, two aromatic rings, and one hydrophobic feature [47].

- Virtual Screening: Over 214,000 compounds from InterBioScreen and ZINC databases were screened against the pharmacophore model.

- Molecular Docking: Twenty-eight mapped compounds were docked against KRAS G12D, with four hits showing higher binding affinity than the reference inhibitor BI-2852.

- MD Validation: 100ns MD simulations confirmed stable binding and favorable free energy calculations for the top hits [47].

Performance Limitations of Classical Methods

While classical computational approaches have contributed significantly to KRAS drug discovery, they face fundamental limitations in scaling and accuracy. Classical force field-based docking struggles to capture KRAS's highly dynamic conformational landscape [48]. Molecular docking simulations are computationally expensive and frequently fail to scale across diverse chemical structures [49]. Deep learning models require large labeled datasets often scarce in drug discovery and struggle with high-dimensional molecular data, limiting generalization across different drug classes and target proteins [49].

Quantum Computing Approaches: Methodologies and Advantages

Quantum-Enhanced Generative Models

A landmark 2024 study published in Nature Biotechnology demonstrated a hybrid quantum-classical generative model for KRAS inhibitor design [44]. The workflow integrated three key components:

- Quantum Circuit Born Machine (QCBM): A 16-qubit processor generated prior distributions, leveraging quantum superposition and entanglement to explore chemical space.

- Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) Network: A classical deep learning model for sequential data modeling.

- Chemistry42 Platform: Validation and refinement of generated structures [44].

The experimental protocol employed:

- Training Data Curation: Compiled 1.1 million data points from known KRAS inhibitors, VirtualFlow 2.0 screening of 100 million molecules, and STONED algorithm-generated compounds.

- Hybrid Model Training: QCBM generated samples from quantum hardware in each training epoch, trained with reward values calculated using Chemistry42.

- Compound Selection: Generated 1 million compounds screened for pharmacological viability and ranked by protein-ligand interaction scores [44].

This approach yielded two experimentally validated hit compounds (ISM061-018-2 and ISM061-022) demonstrating KRAS binding and functional inhibition in cellular assays [44]. The quantum-enhanced model showed a 21.5% improvement in passing synthesizability and stability filters compared to classical approaches, with success rates correlating approximately linearly with qubit count [44].

Quantum Kernel Methods for Drug-Target Interaction