Qubit-ADAPT-VQE: A Hardware-Efficient Path to Quantum Advantage in Drug Discovery

This article explores Qubit-ADAPT-VQE, an adaptive variational quantum algorithm that constructs hardware-efficient ansatze directly on quantum processors.

Qubit-ADAPT-VQE: A Hardware-Efficient Path to Quantum Advantage in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article explores Qubit-ADAPT-VQE, an adaptive variational quantum algorithm that constructs hardware-efficient ansatze directly on quantum processors. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, we detail its foundational principles, which address key NISQ-era limitations like barren plateaus and deep circuits. The methodological core demonstrates its application in molecular simulation and materials science, while troubleshooting sections cover critical optimizations for noise resilience and resource reduction. Finally, we present validation through real-hardware demonstrations and comparative analyses against classical and other quantum methods, highlighting its potential to revolutionize tasks like molecular energy calculation and drug-target interaction prediction.

Foundations of Qubit-ADAPT-VQE: Overcoming NISQ-Era Limitations for Quantum Chemistry

The Intractability of Exact Solutions on Classical Computers

The fundamental challenge in quantum chemistry lies in solving the electronic Schrödinger equation to determine a molecule's ground-state energy—its lowest possible energy level. This energy dictates stability, reactivity, and physical properties. The mathematical formulation of this problem involves finding the lowest eigenvalue of the molecular electronic Hamiltonian, an operator that encapsulates all electron interactions within the system [1].

The complexity of this Hamiltonian is the primary source of computational intractability. It is expressed as:

[ \hat{\mathcal{H}} = \sum{pq} h{pq} \hat{a}p^\dagger \hat{a}q + \frac{1}{2} \sum{pqrs} g{pqrs} \hat{a}p^\dagger \hat{a}q^\dagger \hat{a}r \hat{a}s ]

where the first term describes one-electron interactions (kinetic energy and nuclear attraction), and the second, more problematic term describes two-electron repulsions [1]. The number of terms in this Hamiltonian grows exponentially with the number of electrons, making exact diagonalization impossible for all but the smallest systems.

Table 1: Molecular Scaling and Computational Demands

| System | Qubits Required | Basis States | Classical Computational Class |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hâ‚‚ (minimal basis) | ~4 | 16 | Tractable |

| Benzene (active space) | 12-14 [2] | ~16,000 | Challenging |

| [4Fe-4S] cluster | 77 [3] | ~1.5 x 10²³ | Intractable |

| 25-qubit system | 25 | ~33 million [4] | Practically impossible |

| Drug-like molecule | 50-100 | 10¹ⵠ- 10³Ⱐ| Completely intractable |

This exponential scaling manifests in the many-body problem, where each electron interacts with every other electron, creating correlations that cannot be treated independently. Classical methods like Full Configuration Interaction (FCI) that attempt exact solutions require representing the wavefunction in a Hilbert space whose dimension grows exponentially with system size [5]. For a system with N spin-orbitbits, the number of basis states is 2^N, creating a memory and computational bottleneck that overwhelms even the most powerful supercomputers for systems beyond approximately 50 spin-orbitals.

The classical computational challenge stems from this exponential scaling. While approximate methods like Density Functional Theory (DFT) and Coupled Cluster offer practical compromises, they can fail dramatically for systems with strong electron correlation, such as transition metal complexes, reaction transition states, and conjugated systems—precisely the systems often most interesting in materials science and drug discovery [5] [6]. For the iron-sulfur clusters prevalent in biological systems like nitrogenase, traditional classical algorithms struggle to solve the correct wave function [3].

Figure 1: The classical computational bottleneck in quantum chemistry emerges from exponential scaling, forcing approximations that compromise accuracy.

Qubit-ADAPT-VQE: A Hardware-Efficient Approach

The Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) represents a hybrid quantum-classical approach designed for Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) devices. It combines quantum state preparation and measurement with classical parameter optimization to find ground state energies [7]. The algorithm operates on the variational principle, where a parameterized wavefunction (ansatz) is prepared on a quantum processor, and its energy is measured and iteratively minimized by adjusting parameters on a classical computer.

The Qubit-ADAPT-VQE algorithm represents a significant advancement over standard VQE by constructing problem-specific, hardware-efficient ansätze directly on the quantum processor [8]. Unlike fixed ansätze like Unitary Coupled Cluster (UCC), which may contain many irrelevant operators for a particular system, ADAPT-VQE grows the ansatz iteratively, adding only the most relevant operators at each step.

The algorithm proceeds through these key steps:

- Initialization: Begin with a reference state, typically Hartree-Fock

- Gradient Evaluation: Compute gradients for all operators in a predefined pool

- Operator Selection: Select the operator with the largest gradient magnitude

- Circuit Growth: Append the corresponding parameterized gate to the circuit

- Parameter Optimization: Optimize all parameters in the expanded ansatz

- Convergence Check: Repeat until gradients fall below a threshold

A critical innovation of Qubit-ADAPT-VQE is its use of hardware-efficient operator pools that guarantee exact ansatz construction while minimizing circuit depths. The algorithm employs a minimal pool size that scales only linearly with the number of qubits, substantially reducing quantum resource requirements compared to fermionic ADAPT-VQE approaches [8].

Table 2: Qubit-ADAPT-VQE Performance Metrics for Molecular Systems

| Molecule | Qubit Count | Circuit Depth Reduction | Measurement Overhead | Achievable Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hâ‚„ | 8 | ~10x [8] | Linear scaling [8] | Chemical accuracy [8] |

| LiH | 12 | Substantial [2] | 99.6% reduction [2] | Chemical accuracy [2] |

| BeHâ‚‚ | 14 | 88% CNOT reduction [2] | Competitive | Chemical accuracy [2] |

| Hâ‚‚O | 12-14 | Order of magnitude [8] | 2-5 measurements/iteration [4] | Robust to noise [4] |

| H₆ (linear) | 12 | >1000 CNOTs (standard) [5] | Dramatically reduced [2] | Chemically accurate with Overlap-ADAPT [5] |

Advanced Protocols and Methodologies

Overlap-ADAPT-VQE Protocol

The Overlap-ADAPT-VQE protocol addresses the local minima problem in standard ADAPT-VQE by using an overlap-guided approach to construct more compact ansätze [5]. This method is particularly valuable for strongly correlated systems where the energy landscape is fraught with minima.

Experimental Procedure:

Target Wavefunction Generation:

- Perform a classical Selected Configuration Interaction (SCI) calculation

- Generate an intermediate target wavefunction that captures essential correlation effects

- This serves as a guide for the quantum ansatz construction

Overlap-Guided Ansatz Growth:

- Instead of energy gradient, use overlap with the target wavefunction to select operators

- At each iteration, choose the operator that maximizes the increase in overlap with the target

- Grow the ansatz until sufficient overlap is achieved

ADAPT-VQE Refinement:

- Use the compact overlap-generated ansatz to initialize a standard ADAPT-VQE procedure

- Complete the convergence using the energy gradient criterion

- This hybrid approach avoids early entrapment in local minima

Validation Metrics:

- Compare final circuit depth and CNOT counts with standard ADAPT-VQE

- Measure convergence rate in iterations required for chemical accuracy

- Assess fidelity with full configuration interaction (FCI) reference

This protocol has demonstrated remarkable efficiency for strongly correlated systems like stretched H₆ chains, producing ultra-compact ansätze suitable for high-accuracy simulations on near-term devices [5].

Greedy Gradient-Free ADAPT-VQE (GGA-VQE) Protocol

The GGA-VQE protocol represents a measurement-efficient variant of ADAPT-VQE that eliminates the costly measurement overhead of traditional implementations [4]. This approach is specifically designed for practical implementation on current quantum hardware.

Experimental Workflow:

Operator Pool Preparation:

- Define a pool of possible quantum gate operations

- This may include hardware-efficient or chemistry-inspired operators

Single-Parameter Optimization:

- For each candidate operator, measure energy at 2-5 different parameter values

- Fit a trigonometric curve (cosine/sine) to the measured energies

- Analytically determine the optimal parameter that minimizes energy for each candidate

Greedy Operator Selection:

- Compare the minimized energies across all candidates

- Select the operator and parameter that yield the lowest energy

- Permanently add this gate to the ansatz with the fixed optimal parameter

Iterative Construction:

- Repeat the process, building the ansatz sequentially

- No global re-optimization of all parameters is performed

- Convergence is achieved when energy improvements fall below threshold

Key Advantages:

- Drastically reduces measurement costs to just 2-5 circuit evaluations per iteration

- Demonstrates inherent noise resilience compared to standard ADAPT-VQE

- Successfully implemented on a 25-qubit quantum computer for the transverse-field Ising model [4]

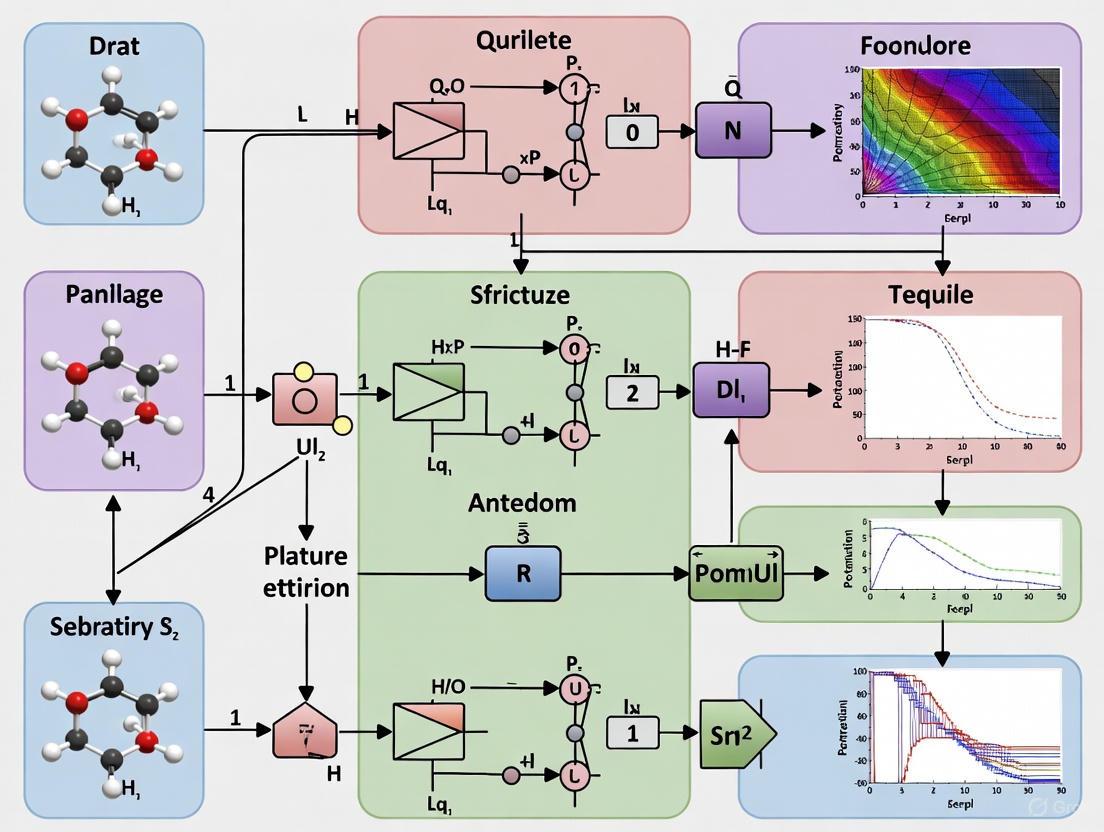

Figure 2: GGA-VQE workflow utilizes a greedy, gradient-free approach to dramatically reduce measurement overhead while maintaining noise resilience.

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Components for Implementation

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Qubit-ADAPT-VQE Experiments

| Component | Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Operator Pools | Provide candidate gates for ansatz construction | Coupled Exchange Operators (CEO) [2], Qubit Excitation-Based (QEB) [5], Fermionic singles and doubles [6] |

| Initial States | Serve as starting point for variational optimization | Hartree-Fock [6], Natural Orbitals from UHF [6], CASSCF reference states [5] |

| Quantum Hardware Platforms | Execute parameterized quantum circuits | Superconducting qubits (IBM) [3] [1], Trapped ions (AQT) [7], Neutral atom arrays [9] |

| Classical Optimizers | Adjust circuit parameters to minimize energy | Broyden-Fletcher-Goldfarb-Shanno (BFGS) [5], Modified COBYLA [1], NFT optimizer [7] |

| Measurement Techniques | Extract energy information from quantum states | Direct measurement [7], Overlap estimation [5], Robust amplitude estimation [10] |

| Error Mitigation Strategies | Counteract decoherence and gate errors | Symmetry verification [1], Zero-noise extrapolation, Readout error correction [4] |

Current Limitations and Future Research Directions

Despite promising advances, significant challenges remain in practical implementation of Qubit-ADAPT-VQE on current quantum hardware. A recent study investigating the capabilities and limitations of ADAPT-VQE algorithms implemented on IBM quantum computers for benzene highlighted that noise levels in today's devices prevent meaningful evaluations of molecular Hamiltonians with sufficient accuracy for reliable quantum chemical insights [1].

The primary constraints include:

Circuit Depth Limitations: Current state-of-the-art simulations on physical quantum computers typically involve maximal circuit depths of less than 100 CNOT gates [5], while chemically accurate ADAPT-VQE for strongly correlated molecules can require thousands of CNOT gates [5].

Measurement Overhead: Even with improvements, the number of measurements required for accurate energy estimation remains substantial, particularly for larger systems [1] [10].

Optimization Challenges: The high-dimensional, non-convex optimization landscapes present difficulties for classical optimizers, particularly in the presence of noise [1] [6].

Future research directions focus on:

- Algorithmic Improvements: Further reductions in circuit depth through better operator pools and initialization strategies [2] [6]

- Hardware Enhancements: Increased qubit coherence times, improved gate fidelities, and larger qubit counts [1]

- Hybrid Approaches: Combining quantum computation with classical machine learning and tensor network methods [9]

- Error Mitigation: Advanced techniques to extract meaningful results from noisy quantum computations [4] [1]

As hardware continues to improve and algorithms become more efficient, the quantum chemistry challenge that currently overwhelms classical computers may become tractable, enabling breakthroughs in drug discovery, materials design, and fundamental chemical understanding.

The advent of noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) computing has necessitated the development of quantum algorithms that can function effectively within stringent hardware constraints, including limited qubit counts, short coherence times, and significant gate errors [11]. Among the most promising approaches for practical quantum simulation on such devices are variational quantum algorithms (VQAs), which employ a hybrid quantum-classical computational paradigm [11]. The variational quantum eigensolver (VQE) stands as a cornerstone application within this class, specifically designed to determine the ground-state energy of quantum systems, a task fundamental to quantum chemistry and materials science [8] [12].

The standard VQE framework operates through a structured sequence. First, a parameterized quantum circuit, known as an ansatz, is initialized. Classical data (such as a molecular Hamiltonian) is embedded into a quantum state through encoding schemes [11]. The quantum processor then executes this circuit to measure the expectation value of the target Hamiltonian. This quantum-measured value is fed to a classical optimizer, which adjusts the circuit parameters to minimize the expectation value, iteratively converging toward the ground-state energy [11]. The performance of VQE is critically dependent on the choice of ansatz, which must navigate a trade-off between expressibility (the ability to represent the true ground state) and computational feasibility (minimizing circuit depth and parameter count to mitigate noise) [8].

Traditional ansatze, such as the Unitary Coupled Cluster (UCC) and hardware-efficient ansatze, often face significant limitations. UCC, while chemically motivated and accurate, typically results in deep quantum circuits that exceed the capabilities of current hardware [13]. Hardware-efficient ansatze, designed with native gate sets to reduce depth, often lack systematic connections to the problem structure and suffer from the barren plateau phenomenon, where gradients vanish exponentially with system size, hindering optimization [8]. These challenges highlighted the need for a more adaptive, problem-specific approach to ansatz design, paving the way for the development of ADAPT-VQE and its subsequent variants.

The ADAPT-VQE Paradigm: A Methodological Breakdown

The ADAPT-VQE (Adaptive Derivative Assembled Pseudo-Trotter Variational Quantum Eigensolver) algorithm represents a fundamental shift from fixed-ansatz approaches. Instead of pre-defining a static circuit architecture, ADAPT-VQE dynamically constructs the ansatz, one operator at a time, selected from a predefined operator pool based on their potential to lower the energy [8]. This iterative, greedy approach tailors the quantum circuit specifically to the problem at hand, often achieving high accuracy with substantially fewer resources than static ansatze [8].

The core innovation of ADAPT-VQE lies in its selection metric. At each iteration, the algorithm computes the gradient of the energy with respect to each operator in the pool. The operator with the largest magnitude gradient is selected and added to the circuit, after which all parameters are re-optimized [8]. This ensures that each new component of the ansatz contributes maximally to progressing toward the ground state. The process terminates when the energy gradient falls below a predefined threshold, indicating convergence.

Table 1: Key Variants of ADAPT-VQE and Their Characteristics

| Variant Name | Core Innovation | Targeted Improvement | Reported Molecular Test Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Qubit-ADAPT-VQE [8] | Uses a pool of qubit-type operators (e.g., Pauli strings) instead of fermionic operators. | Drastic reduction in circuit depth; improved hardware efficiency. | H₄, LiH, H₆ |

| K-ADAPT-VQE [14] | Adds the top K operators from the pool in each iteration. | Reduces total number of iterations and quantum resource calls. | Small molecules (specifics not listed) |

| SC-ADAPT-VQE [15] | Incorporates length-scale symmetry and hierarchy for state preparation. | Creates low-depth circuits with fewer parameters for dynamics. | Schwinger model |

| Qubit-Excitation-Based ADAPT [12] | Employs qubit excitation evolutions. | Reduces gate count while maintaining accuracy. | Not Specified |

A significant advancement within this paradigm is Qubit-ADAPT-VQE, which was developed to directly address the circuit depth problem of the original fermionic ADAPT-VQE [8]. This variant uses a pool of qubit-type operators (e.g., Pauli strings) guaranteed to be sufficient for constructing exact ansatze. The minimal pool size scales only linearly with the number of qubits, and the resulting circuits are demonstrably shallower, reducing depth by an order of magnitude in simulations of molecules like Hâ‚„ and LiH while maintaining accuracy [8]. This makes it a more practical algorithm for NISQ devices. Another notable variant is K-ADAPT-VQE, which batches the addition of multiple operators in each iteration. This strategy reduces the total number of iterative cycles required for convergence, thereby lowering the cumulative number of quantum measurements and accelerating the computation [14].

Experimental Protocols and Workflow Specifications

Standard VQE Workflow

The standard VQE protocol serves as the foundational workflow upon which adaptive variants are built [11].

- Problem Definition: Define the target Hamiltonian (e.g., electronic structure Hamiltonian of a molecule) and map it to a qubit representation using transformations such as Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev.

- Ansatz and Parameter Initialization: Select a fixed ansatz template (e.g., UCCSD, hardware-efficient). Initialize the variational parameters (θ) randomly or using a classical heuristic.

- Quantum Execution: Prepare the ansatz state ( |ψ(θ)⟩ ) on the quantum processor. Measure the expectation value ( ⟨ψ(θ)|H|ψ(θ)⟩ ). This often requires measuring a sum of Pauli terms, which can be grouped for efficiency.

- Classical Optimization: Feed the measured energy to a classical optimizer (e.g., BFGS, SPSA). The optimizer proposes a new set of parameters θ' to minimize the energy.

- Iteration and Convergence: Repeat steps 3 and 4 until the energy converges within a specified threshold (e.g., chemical accuracy of 1.6 × 10â»Â³ Ha) or a maximum number of iterations is reached.

Qubit-ADAPT-VQE Protocol

The Qubit-ADAPT-VQE protocol modifies the standard workflow by integrating an adaptive ansatz construction loop [8].

- Initialization: Define the qubit-mapped Hamiltonian. Define the qubit-operator pool (e.g., all Pauli strings of a certain type). Initialize an empty ansatz circuit and set a convergence threshold ε.

- Gradient Calculation: For the current ansatz state ( |ψ(θ)⟩ ), compute the gradient ( gi = ∂E/∂θi ) for every operator ( T_i ) in the pool. This requires specific quantum circuit measurements to obtain the gradients.

- Operator Selection: Identify the operator ( T{max} ) with the largest gradient magnitude ( |g{max}| ).

- Circuit Growth and Optimization: Append a new parameterized gate ( exp(θ{new} T{max}) ) to the ansatz. Re-optimize all parameters (existing and new) in the now-larger circuit to minimize the energy.

- Convergence Check: If ( |g_{max}| < ε ), the algorithm has converged. Proceed to output. Otherwise, return to Step 2.

Performance Data and Comparative Analysis

Empirical studies across various molecular systems consistently demonstrate the superior resource efficiency of adaptive ansatze over static counterparts.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Different Ansatze on Molecular Systems

| Molecule (Qubits) | Ansatz Type | Number of Parameters | Circuit Depth | Achieved Accuracy (Ha from FCI) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hâ‚‚ (4q) | UCCSD | 54 | ~100 | Chemical Accuracy | [16] |

| Hâ‚‚ (4q) | QuantumDARTS | 51 | Not Specified | Chemical Accuracy | [16] |

| Hâ‚‚ (4q) | FlowQ-Net (Auto-generated) | 3 | Significantly Reduced | Chemical Accuracy | [16] |

| Hâ‚‚O (8q) | UCCSD | 962 | 1,705 | Chemical Accuracy | [16] |

| Hâ‚‚O (8q) | FlowQ-Net (Auto-generated) | 50 | 38 | Chemical Accuracy | [16] |

| Hâ‚„ | Fixed Ansatz | Not Specified | Baseline | Baseline | [8] |

| Hâ‚„ | Qubit-ADAPT-VQE | Not Specified | ~10x shallower | Same accuracy as fixed ansatz | [8] |

The data reveals that automatically designed and adaptive ansatze like those from FlowQ-Net and Qubit-ADAPT-VQE can reduce the number of parameters and circuit depth by an order of magnitude or more while maintaining target accuracy [8] [16]. For instance, in the Hâ‚‚O system, FlowQ-Net reduced parameters from 962 (UCCSD) to 50 and depth from 1,705 to 38 layers [16]. This compactness directly enhances resilience to noise. Furthermore, the K-ADAPT-VQE variant shows that batching operator additions can reduce the total number of iterations and quantum function evaluations required to reach convergence, offering another pathway to computational efficiency on NISQ devices [14].

Table 3: Computational Resource Overhead Comparison

| Algorithm | Measurement Overhead | Classical Optimization Complexity | Noise Resilience |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard VQE (Fixed Ansatz) | Fixed per iteration | Optimizes fixed parameter set; can get stuck in local minima. | Low (due to deep circuits) |

| ADAPT-VQE | High (gradients for full pool each iteration) | Re-optimizes growing parameter set; can avoid barren plateaus. | Medium |

| Qubit-ADAPT-VQE | Scales linearly with qubit count [8] | Same as ADAPT-VQE, but shallower circuits aid convergence. | High (due to shallow circuits) |

| K-ADAPT-VQE | Reduced via batching [14] | Fewer iterations, but more parameters per optimization. | Medium-High |

Essential Research Toolkit

Successfully implementing ADAPT-VQE research requires a suite of software and theoretical tools.

Table 4: The Scientist's Toolkit for ADAPT-VQE Research

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function | Example Platforms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantum Chemistry Packages | Software | Compute molecular integrals, generate fermionic Hamiltonians, provide classical reference values (e.g., FCI). | PySCF, OpenFermion [17] |

| Qubit Mappers | Software | Transform fermionic Hamiltonians into qubit (Pauli) representations. | Jordan-Wigner, Bravyi-Kitaev |

| Quantum SDKs & Simulators | Software | Construct, simulate, and execute quantum circuits; often include VQE modules. | MindSpore Quantum, Q2Chemistry [18] [17], IBM Qiskit |

| Classical Optimizers | Algorithm | Optimize variational parameters using gradient-based or gradient-free methods. | SPSA, BFGS, Adam |

| Operator Pools | Theoretical Construct | Pre-defined sets of operators (fermionic or qubit) from which the ansatz is built. | Qubit-Pool [8], Fermionic-Pool |

| Error Mitigation Techniques | Methods | Reduce the impact of noise on measurement results. | Zero-Noise Extrapolation, Dynamical Decoupling [15] |

| 2-Hydroxyaclacinomycin B | 2-Hydroxyaclacinomycin B | 2-Hydroxyaclacinomycin B is a potent anthracycline antibiotic for cancer research. It inhibits topoisomerase II and RNA synthesis. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. | Bench Chemicals |

| Bitertanol | Bitertanol, CAS:70585-36-3, MF:C20H23N3O2, MW:337.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Software platforms like Q2Chemistry are particularly valuable, providing integrated environments for mapping wave functions to qubit space, generating quantum circuits for various algorithms, and dispatching them to simulators or hardware, with demonstrated scalability up to 72-qubit simulations [18]. Similarly, MindSpore Quantum offers a full stack for developing and benchmarking hybrid quantum-classical algorithms [17].

Future Research Directions and Challenges

Despite their promise, ADAPT-VQE algorithms face several challenges that define the current frontiers of research. The measurement overhead required to compute gradients for large operator pools remains substantial, though linear scaling is a significant improvement [8]. The optimal composition of operator pools for different problem classes is still an open area of investigation [13] [8]. Furthermore, while these algorithms mitigate the issue, the fundamental challenge of barren plateaus and other optimization pathologies in VQAs persists.

Future research is likely to focus on several key areas. Hybrid approaches that combine the principles of adaptive algorithms with machine learning for automated circuit design are emerging as a powerful trend. For example, frameworks like FlowQ-Net use generative models to sample diverse, high-performance circuit architectures based on a user-defined reward function, effectively automating ansatz discovery [16]. Another direction involves extending these adaptive methods beyond ground-state problems to excited-state calculations. Recent work has shown that the convergence path of ADAPT-VQE can be used to construct subspaces for accurately approximating low-lying excited states, a capability with profound implications for quantum chemistry and material science [19]. As quantum hardware continues to evolve, the co-design of adaptive algorithms and device architectures will be crucial for unlocking the full potential of quantum simulation.

The Qubit-Adaptive Derivative-Assembled Problem-Tailored Variational Quantum Eigensolver (Qubit-ADAPT-VQE) represents a significant advancement in quantum computational chemistry, specifically designed to address the limitations of near-term quantum hardware. As a variant of the ADAPT-VQE algorithm, it dynamically constructs efficient, problem-tailored quantum circuits (ansätze) for solving the electronic structure problem, moving beyond static, pre-defined circuit architectures [2]. The algorithm was developed to overcome a critical bottleneck in quantum simulations: the prohibitively deep quantum circuits required by earlier approaches, which are infeasible for current noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices [8] [20].

The core innovation of Qubit-ADAPT-VQE lies in its iterative, adaptive construction of the ansatz. Unlike the Unitary Coupled Cluster Singles and Doubles (UCCSD) approach, which uses a fixed, chemically-inspired circuit structure often containing many insignificant terms, Qubit-ADAPT-VQE builds the circuit one operator at a time, selected based on their immediate potential to lower the energy [2] [20]. This method is system-adapted and problem-tailored, meaning the final circuit structure is uniquely suited to the specific molecule and Hamiltonian being simulated, leading to a dramatic reduction in circuit depth and the number of variational parameters [8] [21].

The theoretical foundation rests on the adaptive algorithm principle. It starts with an initial reference state, such as the Hartree-Fock state, and at each iteration, selects the most promising operator from a predefined "pool" of operators by evaluating their energy gradients [8] [2]. The operator with the largest gradient is appended to the ansatz, and the new set of parameters is re-optimized. This process repeats until the energy converges to a desired accuracy, ensuring that every term in the final circuit contributes significantly to the accuracy of the result [8].

The Hardware-Efficient Design Philosophy

The design philosophy of Qubit-ADAPT-VQE is fundamentally centered on hardware efficiency to overcome the constraints of NISQ processors. The primary objective is to minimize quantum circuit depth and the number of entangling gates, which are major contributors to computational errors on current hardware [8] [20].

A key design element is the use of a qubit excitation-based operator pool instead of the fermionic excitation operators used in the original ADAPT-VQE [8]. While fermionic operators are physically intuitive, their implementation on quantum hardware requires deep circuits due to the non-local commutation relations of fermions, which in turn require lengthy Jordan-Wigner strings [8]. Qubit excitation operators, in contrast, are built directly from Pauli operators acting on the qubit Hilbert space. They retain the desirable property of being number-conserving but feature simpler commutation relations, allowing them to be implemented with asymptotically fewer quantum gates [8]. This direct alignment with qubit logic is a cornerstone of its hardware-efficient design.

Furthermore, the algorithm employs a mathematically complete yet minimal operator pool. A critical theoretical result is that the minimal pool size required to guarantee convergence to the exact solution scales only linearly with the number of qubits [8] [21]. This is a substantial improvement over fermionic pools, which can grow quadratically or worse. A smaller pool size directly translates to a lower measurement overhead during the operator selection step, as fewer gradients need to be evaluated in each iteration [8].

This philosophy stands in contrast to the Hardware-Efficient Ansatz (HEA), which uses device-native gates but is agnostic to the problem being solved. While HEA can produce shallow circuits, it often suffers from barren plateaus—regions where gradients vanish exponentially with system size, making classical optimization intractable [22]. Qubit-ADAPT-VQE, by being adaptive and problem-tailored, is empirically less prone to these issues, striking a balance between hardware efficiency and chemical accuracy [2] [22].

Performance and Resource Analysis

Numerical simulations demonstrate that Qubit-ADAPT-VQE achieves accuracy comparable to its fermionic counterpart while requiring significantly fewer quantum resources. Studies on molecules such as H₄, LiH, and H₆ showed that Qubit-ADAPT-VQE reduces quantum circuit depth by an order of magnitude [8] [21].

The table below summarizes key performance metrics from these simulations, illustrating the algorithm's efficiency.

Table 1: Representative Performance Metrics of Qubit-ADAPT-VQE from Early Numerical Simulations

| Molecule | Qubit Count | Circuit Depth Reduction | Key Achievement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hâ‚„ | 8 | ~10x | Matched fermionic ADAPT accuracy with far shallower circuits [8]. |

| LiH | 12 | ~10x | Drastic reduction in CNOT gates [8]. |

| H₆ | 12 | ~10x | Maintained chemical accuracy with linear-scaling pool [8]. |

The resource reduction extends beyond just circuit depth. The measurement cost, a critical factor for runtime on quantum hardware, is also managed effectively. The additional measurement overhead of Qubit-ADAPT-VQE compared to fixed-ansatz algorithms scales only linearly with the number of qubits, making it a promising candidate for scaling to larger systems [8].

Recent advancements in 2025 have further pushed the boundaries of resource reduction. The introduction of the Coupled Exchange Operator (CEO) pool and other improved subroutines has led to a state-of-the-art algorithm (CEO-ADAPT-VQE*) that showcases dramatic improvements over the original ADAPT-VQE [2].

Table 2: Resource Reduction of State-of-the-Art CEO-ADAPT-VQE [2]

| Resource Metric | Reduction Compared to Original ADAPT-VQE |

|---|---|

| CNOT Count | Up to 88% |

| CNOT Depth | Up to 96% |

| Measurement Costs | Up to 99.6% |

This modern version also outperforms the UCCSD ansatz in all relevant metrics and offers a five order of magnitude decrease in measurement costs compared to other static ansätze with similar CNOT counts, bringing practical quantum advantage closer to reality [2].

Experimental Protocols and Application Workflow

Implementing Qubit-ADAPT-VQE involves a well-defined hybrid quantum-classical workflow. The following protocol provides a detailed methodology for running a molecular ground state simulation using this algorithm.

Initialization and Pre-processing

- Define the Molecular System: Specify the molecule and its nuclear geometry.

- Classical Electronic Structure Calculation: Perform a classical Hartree-Fock calculation for the system. This provides the initial reference state, ( \vert \psi{\text{ref}} \rangle ), and the second-quantized electronic Hamiltonian, ( \hat{H}{el} ) (see Eq. 2 in [20]).

- Qubit Hamiltonian Mapping: Map the fermionic Hamiltonian to a qubit Hamiltonian using a transformation such as Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev. The result is a Hamiltonian expressed as a sum of Pauli strings, ( \hat{H} = \sumj \alphaj P_j ) (see Eq. 3 in [20]).

- Prepare the Operator Pool: Construct the qubit operator pool. A common choice is a set of all distinct Qubit single-excitation and double-excitation operators that conserve particle number [8].

The Adaptive Iteration Loop

The core of the algorithm is an iterative loop that continues until the energy converges to within chemical accuracy (typically 1.6 mHa).

- Gradient Calculation: For each operator ( Ai ) in the operator pool, compute the energy gradient (or an approximation thereof) with respect to the current variational state ( \vert \psi(\vec{\theta}) \rangle ): ( gi = \left\langle \psi(\vec{\theta}) \middle\vert [\hat{H}, A_i] \middle\vert \psi(\vec{\theta}) \right\rangle ). This step requires measuring the expectation values of these commutators on the quantum computer.

- Operator Selection: Identify the operator ( Ak ) with the largest absolute gradient, ( \lvert gk \rvert ).

- Ansatz Growth: Append the corresponding unitary, ( \exp(\thetak Ak) ), to the current ansatz circuit. Initialize the new parameter ( \theta_k ) to zero or a small random value.

- Parameter Optimization: Re-optimize the entire vector of variational parameters ( \vec{\theta} ) to minimize the expectation value of the energy, ( E(\vec{\theta}) = \left\langle \psi(\vec{\theta}) \middle\vert \hat{H} \middle\vert \psi(\vec{\theta}) \right\rangle ). This is done using a classical optimizer (e.g., BFGS, Nelder-Mead).

- Convergence Check: If ( \lvert g_k \rvert < \text{threshold} ), the algorithm is considered converged. Otherwise, return to Step 1.

The following diagram illustrates this iterative workflow:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table details the key computational "reagents" required to implement Qubit-ADAPT-VQE, analogous to the essential materials in a wet-lab experiment.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Qubit-ADAPT-VQE

| Tool/Reagent | Function & Specification | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Qubit Operator Pool | A predefined set of operators (e.g., qubit-excitation operators) from which the ansatz is built. It must be mathematically complete [8]. | The pool should be minimal to reduce measurement overhead. Size scales linearly with qubit count [8]. |

| Gradient Evaluation Subroutine | A quantum routine to measure the gradients ( \langle [H, A_i] \rangle ) for operator selection [8] [2]. | This is a major source of measurement cost. Advanced techniques (e.g., overlapping measurements) can reduce this overhead [2]. |

| Classical Optimizer | A classical algorithm (e.g., gradient-based or gradient-free) to minimize the energy with respect to the variational parameters [20]. | Must be robust to quantum shot noise. The choice impacts convergence speed and reliability. |

| Qubit Hamiltonian | The molecular Hamiltonian translated into a sum of Pauli strings via Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev mapping [20]. | The number of Pauli terms scales as ( O(N^4) ) with orbital count N, affecting measurement requirements. |

| Wavefunction Ansatz | The dynamically constructed quantum circuit, expressed as a product of parametrized unitaries: ( \vert \psi(\vec{\theta}) \rangle = \prodk e^{\thetak Ak} \vert \psi{\text{ref}} \rangle ) [8]. | The circuit is grown iteratively. Its final depth and parameter count are not known a priori. |

| Shatavarin IV | Shatavarin IV, CAS:84633-34-1, MF:C45H74O17, MW:887.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Artocarpesin | Artocarpesin, CAS:3162-09-2, MF:C20H18O6, MW:354.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Qubit-ADAPT-VQE represents a paradigm shift towards adaptive, hardware-efficient algorithms for quantum simulation. Its core principles of dynamic ansatz construction and qubit-focused design directly address the most pressing constraints of NISQ devices, enabling significantly shallower circuits and reduced resource requirements while maintaining high accuracy.

The field continues to evolve rapidly. The recent introduction of the CEO pool and other refinements demonstrates that further drastic reductions in CNOT counts and measurement costs are achievable [2]. Future research directions include optimizing the measurement process for the gradient calculation, developing strategies for error-mitigation tailored to adaptive circuits, and exploring applications beyond ground-state chemistry, such as excited states and condensed matter systems [2]. As quantum hardware matures, Qubit-ADAPT-VQE and its derivatives are poised to be leading contenders for demonstrating a practical quantum advantage in computational chemistry and materials science.

Mitigating Barren Plateaus and Achieving Compact Circuit Structures

Variational Quantum Algorithms (VQAs), particularly the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE), have emerged as promising approaches for quantum chemistry simulations on near-term quantum hardware. However, their practical implementation faces two significant challenges: the barren plateau (BP) problem, where gradients vanish exponentially with system size, and the need for compact circuit structures that can be executed within the limited coherence times of noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices. The Qubit-ADAPT-VQE algorithm addresses both challenges through its adaptive, problem-informed construction of quantum circuits, offering a pathway toward practical quantum advantage in computational chemistry and drug development.

Understanding Barren Plateaus and Their Impact

Barren plateaus represent a fundamental obstacle in scaling VQAs for quantum chemistry applications. This phenomenon describes the exponential decay of cost function gradients with increasing qubit count, rendering optimization practically impossible for large systems [23]. Specifically, under the assumption of Haar random circuits, the variance of the gradient Var[∂C] vanishes exponentially with the number of qubits, creating a flat energy landscape where optimization algorithms stall [23].

The Hardware Efficient Ansatz (HEA), while designed to minimize hardware noise, is particularly susceptible to BPs, especially for problems with volume law entanglement scaling [22]. This is critically relevant for quantum chemistry applications, where electronic wavefunctions often exhibit complex entanglement patterns. The BP problem thereby threatens the viability of VQE for simulating molecular systems of practical interest in drug development.

Table 1: Barren Plateau Mitigation Strategies in VQE Approaches

| Strategy | Mechanism | Effectiveness | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shallow Circuits | Limits entanglement formation | Effective for area law data [22] | Reduced expressibility |

| Local Cost Functions | Uses local observables instead of global | Avoids exponential gradient decay [2] | Not always physically relevant |

| Identity Initialization | Starts near identity operation | Preserves gradients in early optimization [2] | Limited to specific ansatzes |

| Problem-Inspired Ansatzes | Leverages physical symmetries | BP-free and chemically relevant [2] | May enable classical simulation [2] |

| Adaptive Construction | Dynamically builds circuits | Avoids BP via system-tailored approach [2] | High measurement overhead |

Qubit-ADAPT-VQE: Algorithmic Framework and Advantages

Core Algorithmic Principles

Qubit-ADAPT-VQE represents an evolution beyond fixed-ansatz VQE approaches by dynamically constructing hardware-efficient ansätze tailored to specific molecular systems. The algorithm iteratively builds the ansatz by selecting operators from a predefined pool that maximally reduce the energy at each step [8] [2]. This methodology stands in contrast to static ansatzes like the Unitary Coupled Cluster Singles and Doubles (UCCSD), which incorporate potentially redundant operators that increase circuit depth without proportional benefit [24] [2].

The mathematical formulation of the Qubit-ADAPT-VQE wavefunction is:

[ |\Psi^{(m)}\rangle = \prod{i=1}^{m} e^{\thetai \hat{A}i} |\psi0\rangle ]

where (\hat{A}i) are the adaptively selected operators, (\thetai) are the optimization parameters, and (|\psi_0\rangle) is the reference state (typically Hartree-Fock) [24]. The operator selection criterion is based on the gradient of the energy with respect to each candidate operator:

[ \mathcal{U}^* = \underset{\mathcal{U} \in \mathbb{U}}{\text{argmax}} \left| \frac{d}{d\theta} \langle \Psi^{(m)} | \mathcal{U}(\theta)^\dagger \hat{H} \mathcal{U}(\theta) | \Psi^{(m)} \rangle \Big|_{\theta=0} \right| ]

where (\mathbb{U}) represents the operator pool [25]. This gradient-based selection ensures that each added operator meaningfully contributes to lowering the energy, creating an efficient pathway toward the ground state.

Barren Plateau Mitigation Mechanisms

Qubit-ADAPT-VQE addresses the barren plateau problem through multiple interconnected mechanisms:

System-Tailored Ansatz Construction: Unlike fixed ansatzes that may explore irrelevant regions of Hilbert space, Qubit-ADAPT-VQE constructs circuits specifically adapted to the problem Hamiltonian. This tailored approach avoids the Haar randomness that underlies BP phenomena [2]. Empirical evidence suggests that ADAPT-VQE variants are among the few VQAs that combine BP resistance with classical non-simulability [2].

Incremental Hilbert Space Exploration: By adding one operator at a time and reoptimizing all parameters, the algorithm maintains a compact circuit structure throughout the optimization process. This incremental approach prevents the algorithm from entering flat energy landscapes characteristic of BPs [24] [2].

Gradient-Based Operator Selection: The greedy selection criterion ensures that each new operator significantly impacts the energy landscape, maintaining substantial gradients throughout the optimization process [24] [25].

Compact Circuit Structures: The algorithm naturally constructs shorter circuits with fewer parameters compared to fixed ansatzes, reducing the parameter space and mitigating gradient vanishing [8] [2].

Quantitative Performance and Resource Reduction

The resource efficiency of Qubit-ADAPT-VQE has been demonstrated across multiple molecular systems. Recent advancements, including the Coupled Exchange Operator (CEO) pool, have dramatically reduced quantum computational resources compared to early ADAPT-VQE implementations [2].

Table 2: Resource Reduction in State-of-the-Art ADAPT-VQE Implementations

| Molecular System | Qubit Count | CNOT Reduction | CNOT Depth Reduction | Measurement Cost Reduction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LiH | 12 | 88% | 96% | 99.6% |

| H₆ | 12 | 85% | 95% | 99.4% |

| BeHâ‚‚ | 14 | 82% | 94% | 99.2% |

Data adapted from [2] showing performance of CEO-ADAPT-VQE* compared to original ADAPT-VQE.

The compactness of Qubit-ADAPT-VQE circuits directly contributes to their trainability by reducing the circuit depth and parameter count. For the Hâ‚„ system at stretched geometry (3.0 Ã…), ADAPT-VQE with pruning techniques successfully achieves chemical accuracy while maintaining manageable circuit sizes [24]. This demonstrates the algorithm's effectiveness for strongly correlated systems relevant to drug development, such as simulating transition states in chemical reactions.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard Qubit-ADAPT-VQE Protocol

Objective: Prepare the ground state of a target molecular Hamiltonian (\hat{H}) with energy accuracy ≤ 1 mHa (chemical accuracy).

Initialization:

- Prepare reference state (|\psi_0\rangle) (typically Hartree-Fock)

- Select operator pool (\mathbb{U}) (e.g., qubit excitation operators)

- Set convergence threshold (\epsilon = 10^{-3}) Ha for energy gradients

- Initialize empty ansatz list: (\mathbb{A} = [\ ])

Iterative Procedure:

- Gradient Calculation: For all operators (Ui) in pool (\mathbb{U}), compute: [ gi = \left| \frac{d}{d\theta} \langle \psi | Ui(\theta)^\dagger \hat{H} Ui(\theta) | \psi \rangle \Big|_{\theta=0} \right| ] where (|\psi\rangle) is the current ansatz state.

Operator Selection: Identify operator (Uk) with maximum gradient (gk = \maxi gi).

Convergence Check: If (g_k < \epsilon), terminate algorithm and return current ansatz.

Ansatz Expansion: Append selected operator to ansatz: (\mathbb{A}.\text{append}(Uk(\thetam))), where (m) is current iteration count.

Global Optimization: Optimize all parameters in expanded ansatz: [ \vec{\theta}^* = \underset{\vec{\theta}}{\text{argmin}} \langle \psi(\vec{\theta}) | \hat{H} | \psi(\vec{\theta}) \rangle ] where (|\psi(\vec{\theta})\rangle = \prod{Ui \in \mathbb{A}} Ui(\thetai) |\psi_0\rangle).

Iteration: Return to step 1 with updated ansatz.

Output: Optimized parameterized quantum circuit preparing approximate ground state of (\hat{H}).

Pruned-ADAPT-VQE Protocol for Enhanced Compactness

Objective: Further reduce ansatz size by eliminating redundant operators while maintaining accuracy.

Initialization:

- Run standard Qubit-ADAPT-VQE for (N) iterations

- Set pruning threshold (\delta) based on parameter magnitudes (typically (10^{-3}) to (10^{-4}))

- Initialize operator importance function (I(U_i)) that considers both parameter value and position in ansatz

Pruning Procedure:

- Operator Evaluation: After ADAPT-VQE convergence, evaluate each operator (Ui) in ansatz using: [ I(Ui) = |\theta_i| \times f(i) ] where (f(i)) is a position-dependent weighting function.

Threshold Application: Identify operators with (I(U_i) < \delta) as candidates for removal.

Validation: Remove candidate operators one at a time, reoptimizing remaining parameters after each removal.

Convergence Check: Ensure energy change after removal < (\epsilon) (chemical accuracy).

Final Circuit: Return pruned ansatz with reduced operator count.

Applications: Particularly effective for systems with flat energy landscapes where ADAPT-VQE may select superfluous operators [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Components for Qubit-ADAPT-VQE Implementation

| Component | Function | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Operator Pools | Provides set of operators for adaptive selection | Qubit pools offer hardware efficiency [8]; CEO pools enhance resource reduction [2] |

| Gradient Calculators | Computes selection criteria for operators | Can be evaluated simultaneously for multiple operators to reduce measurements [25] |

| Classical Optimizers | Optimizes parameters in quantum circuit | BFGS algorithm effective in noiseless simulations [24]; resilient optimizers needed for noisy hardware |

| Wavefunction Ansatz | Parameterized quantum circuit | Constructed iteratively; initial state typically Hartree-Fock [2] |

| Measurement Schemes | Evaluates expectation values | Reduced measurement strategies critical for practicality [2] [25] |

| Convergence Monitors | Tracks algorithm progress | Multiple criteria: gradient magnitude, energy improvement, parameter values [24] |

| Masoprocol | Masoprocol, CAS:27686-84-6, MF:C18H22O4, MW:302.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| altertoxin III | Altertoxin III|CAS 105579-74-6|For Research | Altertoxin III is a mutagenic perylene quinone from Alternaria fungi. This product is for research use only (RUO) and not for human or veterinary use. |

Advanced Applications and Protocol Extensions

Excited State Calculations

The ADAPT-VQE convergence path can be repurposed for excited state calculations with minimal quantum resource overhead. The methodology involves:

State Sampling: Collect intermediate states from the ADAPT-VQE convergence path toward the ground state.

Subspace Construction: Use these states as a basis for a subspace diagonalization approach.

Quantum Subspace Diagonalization: Solve the eigenvalue problem in the constructed subspace to obtain approximations to low-lying excited states.

This approach has been successfully applied to molecular systems like Hâ‚„ and nuclear pairing problems, demonstrating accuracy comparable to ground state calculations with only modest resource overhead [26].

Noise-Resilient Implementation (GGA-VQE)

For hardware implementations, the Greedy Gradient-free Adaptive VQE (GGA-VQE) protocol offers enhanced resilience to statistical noise:

Gradient-Free Optimization: Replace gradient-based parameter optimization with analytic, gradient-free methods.

Iterative Ansatz Construction: Retain the adaptive operator selection of ADAPT-VQE.

Error Mitigation: Incorporate measurement error mitigation and robust observable estimation.

This approach has been demonstrated on a 25-qubit error-mitigated quantum processing unit for a 25-body Ising model, showing favorable ground-state approximations despite hardware noise [25].

Qubit-ADAPT-VQE represents a significant advancement in variational quantum algorithms for quantum chemistry, directly addressing the critical challenges of barren plateaus and circuit compactness. Through its adaptive, problem-informed approach, the algorithm constructs system-tailored ansätze that maintain substantial gradients throughout optimization while minimizing quantum resource requirements. The experimental protocols outlined provide researchers with practical methodologies for implementing these techniques, with applications ranging from ground state calculations to excited state simulations. As quantum hardware continues to evolve, these algorithmic advances promise to enable increasingly complex molecular simulations relevant to drug development and materials design.

The design of the operator pool is a foundational element of the ADAPT-VQE (Adaptive Derivative-Assembled Problem-Tailored Variational Quantum Eigensolver) algorithm, critically determining its efficiency, accuracy, and hardware feasibility. As a dynamically constructive algorithm, ADAPT-VQE iteratively builds problem-specific ansätze by selecting operators from a predefined pool based on their potential to lower the energy [2]. The choice of pool dictates not only the convergence rate and circuit depth but also the measurement overhead and resilience to noise, making it a central focus for algorithmic improvement in the Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) era.

Early versions of ADAPT-VQE employed fermionic operator pools, such as the Generalized Single and Double (GSD) excitation pool. While these pools guarantee convergence to the exact ground state, they lead to quantum circuits with depths that are often prohibitive for near-term devices and incur a significant measurement burden due to the polynomial scaling of pool size with the number of qubits (typically (O(N^4)) [2] [27]. This motivated the development of hardware-efficient pools that maintain convergence guarantees while drastically reducing resource requirements. The evolution from fermionic to qubit-representation pools represents a pivotal shift toward making quantum chemistry simulations practical on available hardware.

The Evolution of Operator Pools: A Comparative Analysis

Fermionic and Qubit-Based Pools

The original ADAPT-VQE formulation used a fermionic pool consisting of spin-complemented single and double excitations [2]. While mathematically well-grounded in quantum chemistry, the resulting circuits involve non-local operations that translate into deep quantum circuits after compilation to native gates.

The qubit-ADAPT-VQE algorithm introduced a crucial advancement by employing a pool of operators built directly from Pauli strings [8]. This approach is "hardware-efficient" because it uses an operator pool guaranteed to contain the elements needed for exact ansatz construction while simultaneously reducing circuit depths by an order of magnitude compared to the original fermionic ADAPT-VQE [8]. A key result of this work was proving that the minimal pool size needed for convergence scales only linearly with the number of qubits, a significant reduction from the (O(N^4)) scaling of fermionic pools.

The Coupled Exchange Operator (CEO) Pool

A more recent innovation is the Coupled Exchange Operator (CEO) pool, which further optimizes the pool design for resource reduction. The CEO pool achieves dramatic improvements in quantum resource requirements: reducing CNOT counts by 88%, CNOT depth by 96%, and measurement costs by 99.6% compared to the original fermionic ADAPT-VQE for molecules represented by 12 to 14 qubits [2]. This substantial reduction brings the algorithm closer to being practically executable on near-term quantum processors.

Table 1: Comparison of Operator Pool Properties

| Pool Type | Typical Pool Size Scaling | Circuit Depth | Measurement Cost | Convergence Guarantee |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fermionic (GSD) | (O(N^4)) | High | Very High | Yes |

| Qubit-ADAPT | Linear with qubit number [8] | Substantially reduced [8] | Reduced | Yes [8] |

| CEO Pool | Not specified | Lowest (4-8% of GSD) [2] | Drastically reduced (0.4-2% of GSD) [2] | Yes |

Performance Benchmarking

Numerical simulations across various molecular systems demonstrate the progressive improvement offered by next-generation operator pools. CEO-ADAPT-VQE outperforms the widely-used Unitary Coupled Cluster Singles and Doubles (UCCSD) ansatz across all relevant metrics and offers a five-order-of-magnitude decrease in measurement costs compared to other static ansätze with similar CNOT counts [2].

Table 2: Resource Reduction of CEO-ADAPT-VQE vs Original ADAPT-VQE at Chemical Accuracy [2]

| Molecule (Qubit Count) | CNOT Count (% of Original) | CNOT Depth (% of Original) | Measurement Costs (% of Original) |

|---|---|---|---|

| LiH (12 qubits) | 12% | 4% | 0.4% |

| H6 (12 qubits) | 27% | 8% | 2% |

| BeH2 (14 qubits) | 19% | 6% | 1% |

Experimental Protocols for Operator Pool Evaluation

Protocol 1: Comparative Performance Analysis

Objective: To evaluate and benchmark the performance of different operator pools for molecular ground-state energy estimation.

Methodology:

- System Selection: Choose a set of test molecules (e.g., LiH, H6, BeH2) at various bond lengths, including dissociated geometries where electron correlation effects are strong.

- Hamiltonian Preparation: Generate the molecular Hamiltonian in the qubit basis using an appropriate fermion-to-qubit mapping (e.g., Jordan-Wigner, Bravyi-Kitaev, or PPTT mappings) [27].

- Algorithm Execution: Run ADAPT-VQE with different operator pools (GSD, qubit, CEO):

- Initialize with the Hartree-Fock state.

- At each iteration, calculate the gradient for every operator in the pool.

- Select the operator with the largest gradient magnitude and add it to the ansatz.

- Optimize all parameters in the ansatz.

- Data Collection: Track the number of iterations, parameters, CNOT gates, circuit depth, and total energy evaluations until convergence to chemical accuracy (1.6 mHa).

Validation: Compare the converged energy with full configuration interaction (FCI) results where classically tractable.

Protocol 2: Resource Assessment for NISQ Implementation

Objective: To quantify the practical hardware requirements for implementing CEO-ADAPT-VQE on near-term quantum processors.

Methodology:

- Circuit Compilation: Transpile the optimized ansatz circuit to native hardware gates (e.g., single-qubit rotations and CNOTs) respecting device connectivity constraints.

- Resource Metrics Calculation:

- Count the number of two-qubit gates (primary source of error).

- Calculate the critical CNOT depth.

- Estimate the total number of measurements required for energy estimation throughout the entire optimization process.

- Noise Simulation: Simulate the algorithm performance under realistic noise models to determine achievable accuracy thresholds.

- Treespilation Optimization: Apply architecture-aware fermion-to-qubit mapping optimization (e.g., Treespilation technique) to further reduce circuit complexity [27].

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: ADAPT-VQE Algorithm Workflow with Operator Pool Selection. This flowchart illustrates the complete ADAPT-VQE protocol, highlighting the central role of operator pool selection in the iterative ansatz construction process. The red diamond nodes represent critical decision points, while the blue node indicates the key step where the operator pool is utilized.

Diagram 2: Evolution of Operator Pool Designs. This visualization compares the development trajectory from fermionic to qubit-based operator pools, highlighting the progressive improvement in key resource metrics including pool size scaling, circuit depth, and measurement requirements.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for ADAPT-VQE Implementation

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function & Importance |

|---|---|---|

| Fermion-to-Qubit Mappings | Jordan-Wigner, Bravyi-Kitaev, PPTT mappings [27] | Transform electronic structure Hamiltonians from fermionic to qubit representation while minimizing circuit complexity. |

| Operator Pools | Fermionic (GSD), Qubit-ADAPT, CEO pool [8] [2] | Define the set of available gates for ansatz construction, directly impacting convergence and efficiency. |

| Measurement Techniques | Informationally Complete POVMs (AIM) [27] | Reduce measurement overhead by enabling classical simulation of pool selection steps. |

| Circuit Compilation Tools | Treespilation [27] | Optimize quantum circuit implementation for specific hardware architectures to minimize gate count and depth. |

| Classical Optimizers | Gradient-based, BFGS, SPSA | Efficiently navigate parameter landscape to find energy minima in the variational quantum algorithm. |

| 3-Methylglutaric acid | 3-Methylglutaric acid, CAS:626-51-7, MF:C6H10O4, MW:146.14 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Furprofen | Furprofen, CAS:66318-17-0, MF:C14H12O4, MW:244.24 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The strategic design of operator pools has proven to be a decisive factor in advancing the practicality of ADAPT-VQE for quantum chemistry simulations. The evolution from fermionic excitation pools to hardware-efficient qubit representations, culminating in the recent CEO pool, has driven remarkable reductions in quantum resource requirements—lowering CNOT counts, circuit depths, and measurement overheads by orders of magnitude. These improvements have transformed ADAPT-VQE from a theoretical algorithm to a promising candidate for implementation on near-term quantum devices.

Looking forward, several research directions appear particularly promising. First, the continued co-design of operator pools and hardware architectures, potentially leveraging machine learning techniques to dynamically generate application-specific pools, could yield further efficiency gains. Second, the integration of error mitigation techniques tailored to specific pool characteristics may extend the achievable system sizes on NISQ processors. Finally, the development of application-specific pools targeting particular chemical problems, such as transition metal complexes or excited states, could accelerate the path to practical quantum advantage in computational chemistry and drug discovery. As these advancements mature, ADAPT-VQE with optimized operator pools is poised to become an indispensable tool for exploring molecular systems beyond the reach of classical computation.

Implementing Qubit-ADAPT-VQE: Methodologies and Real-World Drug Discovery Applications

The pursuit of quantum advantage in molecular simulation on Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) devices has catalyzed the development of hybrid quantum-classical algorithms that can overcome the limitations of fixed-structure ansätze. Among these, adaptive variational quantum eigensolvers represent a paradigm shift in ansatz construction, moving from predetermined circuit architectures to dynamically grown, problem-tailored approaches. The fundamental innovation of ADAPT-VQE lies in its iterative construction of quantum circuits, which systematically builds expressive ansätze while minimizing resource overhead—a critical consideration for current quantum hardware [25] [2].

Traditional variational quantum algorithms face significant challenges including barren plateaus, high-dimensional optimization landscapes, and measurement overhead that scales unfavorably with system size. The adaptive algorithm loop addresses these limitations through a greedy, iterative methodology that selects the most relevant operators at each step based on their potential to lower the energy expectation value [2] [28]. By constructing circuits that are specifically tailored to both the target Hamiltonian and the current variational state, these algorithms achieve a favorable balance between expressibility and hardware efficiency, making them particularly suitable for the constraints of NISQ-era quantum devices [8] [29].

The Core Adaptive Loop: Mechanism and Workflow

Fundamental Algorithmic Steps

The adaptive variational algorithm operates through a structured iterative process that dynamically constructs an optimal ansatz circuit. The core loop consists of two principal phases executed sequentially until convergence criteria are met [25] [30]:

Operator Selection: At iteration m, with a current parameterized ansatz wavefunction |Ψ^(m-1)⟩, the algorithm evaluates a predefined operator pool to identify the most promising unitary operator to append. The selection criterion typically involves identifying the operator Ʋ* ∈ 𕌠that maximizes the gradient of the energy expectation value with respect to the new parameter at θ=0 [25]. This gradient-based prioritization ensures that each added operator provides the greatest potential energy reduction.

Parameter Optimization: Following operator selection, the algorithm solves an m-dimensional optimization problem to minimize the energy expectation value across all parameters in the expanded ansatz. The optimization yields the refined parameter set {θ1^(m), ..., θm^(m)} that defines the updated state |Ψ^(m)⟩ [25]. This comprehensive reoptimization, while computationally demanding, ensures that the entire parameter space is explored to maximize algorithmic efficiency.

The following diagram illustrates this iterative workflow:

Mathematical Foundation

The mathematical framework underlying ADAPT-VQE is rooted in the variational principle of quantum mechanics. Given a parameterized wavefunction |Ψ(θ)⟩ = Πi e^{θi Âi}|ψ0⟩, where {Â_i} are excitation operators from a predefined pool, the energy expectation value E(θ) = ⟨Ψ(θ)|Ĥ|Ψ(θ)⟩ serves as the cost function [28]. The adaptive selection criterion leverages the energy gradient with respect to potential new parameters:

∇k E = ∂/∂θk ⟨Ψ^(m-1)|e^{-θk Âk^†} Ĥ e^{θk Âk}|Ψ^(m-1)⟩│{θk=0}

This gradient can be expressed as a commutator expectation value [Ĥ, Â_k],

which can be measured efficiently on quantum hardware without additional analytic gradient circuits [25] [2]. The operator with the largest gradient magnitude is selected for inclusion in the growing ansatz, ensuring maximal improvement per iteration.

Qubit-ADAPT-VQE: A Hardware-Efficient Variant

Algorithmic Innovations

Qubit-ADAPT-VQE represents a significant advancement in hardware-efficient ansatz construction by addressing the fundamental limitations of fermionic ADAPT-VQE approaches. Where traditional fermionic ADAPT employs chemistry-inspired operator pools derived from unitary coupled cluster theory, Qubit-ADAPT utilizes a pool of qubit excitation operators that directly correspond to native gate operations on quantum hardware [8] [29]. This fundamental restructuring of the operator pool dramatically reduces circuit depths—by an order of magnitude in practice—while maintaining theoretical guarantees of convergence [8].

The algorithm employs a minimal operator pool that scales linearly with the number of qubits, in contrast to the quartic scaling of traditional UCCSD pools [8] [29]. This reduction in pool size directly translates to decreased measurement overhead during the operator selection phase, as fewer gradients need to be evaluated at each iteration. Importantly, the qubit-ADAPT pool is mathematically guaranteed to contain all operators necessary to construct exact ansätze, preserving the algorithmic completeness while enhancing hardware compatibility [29].

Performance and Resource Reduction

Numerical simulations across various molecular systems demonstrate the substantial advantages of Qubit-ADAPT-VQE over its fermionic counterpart. For the H₄, LiH, and H₆ systems, Qubit-ADAPT achieves comparable accuracy to fermionic ADAPT-VQE while reducing circuit depth by approximately tenfold [8]. This dramatic reduction is attributed to the elimination of redundant operators and the direct mapping of selected operators to hardware-efficient gate sequences.

The measurement overhead of Qubit-ADAPT compared to fixed-ansatz variational algorithms scales only linearly with the number of qubits, making it particularly suitable for scaling to larger quantum simulations [8]. This favorable scaling arises from the efficient operator pool design and the reduced number of iterations required to achieve chemical accuracy, establishing Qubit-ADAPT as a promising approach for practical quantum advantage on near-term devices.

Advanced ADAPT-VQE Extensions and Optimizations

Greedy Gradient-Free Adaptive VQE (GGA-VQE)

The Greedy Gradient-Free Adaptive VQE algorithm addresses a critical bottleneck in standard ADAPT-VQE: the extensive measurement overhead required for gradient calculations during operator selection [25] [31]. GGA-VQE employs a gradient-free optimization strategy that leverages the mathematical structure of parameterized quantum circuits to dramatically reduce quantum resource requirements [31].

The key innovation of GGA-VQE lies in its operator selection and parameter optimization approach. For each candidate operator, the algorithm:

- Takes a small number of measurement shots to fit the theoretical energy curve as a function of the new parameter

- Analytically determines the angle that minimizes this fitted curve

- Selects the operator that provides the lowest energy at its optimal angle

- Fixes this parameter in the circuit and proceeds to the next iteration [31]

This approach reduces the number of circuit measurements required per iteration to just five, regardless of system size or operator pool dimensions [31]. The following diagram illustrates this streamlined process:

Experimental validation of GGA-VQE on a 25-qubit error-mitigated quantum processing unit demonstrated successful computation of the ground state of a 25-body Ising model, showcasing the algorithm's practical feasibility on current hardware [25] [31]. Although hardware noise produced inaccurate absolute energies, the parameterized quantum circuit generated by GGA-VQE provided a favorable ground-state approximation that could be refined through noiseless emulation [25].

Shot-Efficient ADAPT-VQE with Measurement Reuse

Recent innovations in measurement strategy have yielded significant improvements in ADAPT-VQE efficiency. The Shot-Efficient ADAPT-VQE approach incorporates two complementary techniques to reduce quantum measurement overhead [32]:

Pauli Measurement Reuse: Measurement outcomes obtained during VQE parameter optimization are systematically reused in subsequent operator selection steps, specifically for operator gradient measurements. This strategy capitalizes on the overlapping Pauli strings between the Hamiltonian and the commutators [Ĥ, Â_i] used in gradient evaluations [32].

Variance-Based Shot Allocation: Both Hamiltonian and gradient measurements employ non-uniform shot allocation based on the variance of individual Pauli terms. This optimal resource allocation strategy minimizes the total number of measurements required to achieve a target precision [32].

Numerical simulations demonstrate that these combined strategies reduce average shot usage to approximately 32.29% of the naive full measurement approach when both techniques are applied, and to 38.59% with measurement grouping alone [32]. This substantial reduction in quantum resource requirements enhances the feasibility of ADAPT-VQE for larger molecular systems on current quantum devices.

Coupled Exchange Operators (CEO-ADAPT-VQE)

The CEO-ADAPT-VQE algorithm introduces a novel operator pool design that dramatically reduces quantum computational resources compared to early ADAPT-VQE implementations [2]. The Coupled Exchange Operator pool strategically combines excitation operators to create more effective ansatz elements, resulting in:

- CNOT count reduction of up to 88% for molecules represented by 12 to 14 qubits (LiH, H₆, and BeH₂)

- CNOT depth reduction of up to 96% for the same molecular systems

- Measurement cost reduction of up to 99.6% compared to original ADAPT-VQE implementations [2]

The CEO pool achieves these improvements by leveraging coupled cluster-inspired operator combinations that more efficiently capture electron correlation effects while maintaining hardware efficiency. When enhanced with additional algorithmic improvements (denoted CEO-ADAPT-VQE*), the approach outperforms the Unitary Coupled Cluster Singles and Doubles ansatz in all relevant metrics and offers a five order of magnitude decrease in measurement costs compared to other static ansätze with competitive CNOT counts [2].

Pruned-ADAPT-VQE for Ansatz Compaction

Pruned-ADAPT-VQE addresses the problem of redundant operator accumulation that can occur during the adaptive construction process [28]. Despite the gradient-based selection criterion, ADAPT-VQE can occasionally incorporate operators that contribute minimally to energy reduction, leading to unnecessarily large ansätze. The pruning protocol automatically identifies and removes superfluous operators through a systematic approach that considers:

- Operator parameter magnitude after optimization

- Position within the ansatz circuit structure

- Dynamic thresholding based on recent operator performance [28]

This post-selection strategy reduces ansatz size and accelerates convergence, particularly in systems with flat energy landscapes, while incurring minimal additional computational cost. The pruning mechanism specifically targets three identified sources of redundancy: poor operator selection, operator reordering effects, and fading operators whose contributions diminish as the ansatz grows [28].

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Table 1: Resource Requirements for Different ADAPT-VQE Variants Achieving Chemical Accuracy

| Algorithm Variant | Molecular System | Qubit Count | CNOT Reduction | Measurement Reduction | Key Innovation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CEO-ADAPT-VQE* [2] | LiH, H₆, BeH₂ | 12-14 | 88% | 99.6% | Coupled exchange operators |

| Qubit-ADAPT-VQE [8] | H₄, LiH, H₆ | 8-12 | ~90% (circuit depth) | Linear scaling with qubits | Qubit excitation pool |

| GGA-VQE [25] [31] | 25-body Ising model | 25 | Not specified | 5 measurements/iteration | Gradient-free optimization |

| Shot-Efficient ADAPT [32] | Hâ‚‚ to BeHâ‚‚ | 4-14 | Not specified | 67.71% (vs. naive) | Measurement reuse & allocation |

Table 2: Experimental Protocols for Key ADAPT-VQE Implementations

| Protocol Component | Qubit-ADAPT-VQE [8] [29] | GGA-VQE [25] [31] | CEO-ADAPT-VQE [2] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Operator Pool | Qubit excitation operators (scales linearly with qubits) | Fermionic or qubit operators | Coupled exchange operators |

| Selection Metric | Gradient magnitude of energy | Direct energy minimization via curve fitting | Gradient magnitude |

| Parameter Optimization | Global optimization of all parameters | Greedy one-parameter-at-a-time | Global optimization with improved subroutines |

| Measurement Strategy | Standard shot allocation | Fixed 5 measurements per candidate | Advanced measurement techniques |

| Convergence Criterion | Gradient tolerance | Energy improvement threshold | Energy or gradient threshold |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Components

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for ADAPT-VQE Implementation

| Component | Function | Examples/Alternatives |

|---|---|---|

| Operator Pools | Defines candidate gates for ansatz construction | Fermionic (UCCSD), Qubit (pauli strings), CEO (coupled exchange) [8] [2] [29] |

| Quantum Backends | Executes quantum circuits and returns measurement data | Statevector simulators (Qulacs), QPU implementations (trapped-ion, superconducting) [25] [30] |

| Classical Optimizers | Adjusts circuit parameters to minimize energy | L-BFGS-B, BFGS, Gradient-free optimizers [30] |

| Measurement Techniques | Efficient evaluation of expectation values and gradients | Pauli reuse, Variance-based shot allocation, Commutator grouping [32] |

| Qubit Mappings | Transforms fermionic Hamiltonians to qubit representations | Jordan-Wigner, Bravyi-Kitaev [28] |

| Error Mitigation | Reduces impact of hardware noise on results | Zero-noise extrapolation, Readout error mitigation [25] |

| Valethamate Bromide | Valethamate Bromide Research Grade|Anticholinergic Agent | Valethamate bromide is an anticholinergic research compound for investigating smooth muscle spasms and cervical dilation. For Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. |

| Cyathin A3 | Cyathin A3|Diterpenoid for NGF Research | Cyathin A3 is a fungal diterpenoid for research on nerve growth factor (NGF) induction and anti-inflammatory mechanisms. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

The landscape of adaptive variational quantum algorithms has evolved dramatically since the introduction of ADAPT-VQE, with current implementations demonstrating orders-of-magnitude improvements in quantum resource requirements [2]. The iterative ansatz construction framework has proven to be a versatile foundation for algorithmic innovation, enabling hardware-efficient approaches like Qubit-ADAPT-VQE, measurement-frugal implementations like GGA-VQE, and highly compact ansätze through CEO pools and pruning techniques [8] [2] [31].

Despite these advances, practical challenges remain for large-scale quantum simulations on NISQ hardware. Measurement overhead, while substantially reduced, continues to present scaling limitations [32]. Hardware noise and gate errors necessitate further development of error mitigation strategies tailored to adaptive algorithms [25]. The integration of machine learning techniques for operator selection and parameter initialization represents a promising direction for future research [33].

The progressive refinement of ADAPT-VQE methodologies highlights a crucial paradigm in quantum algorithm development: the co-design of algorithms, software, and hardware to maximize practical utility [33]. As quantum hardware continues to advance, the adaptive algorithm loop is poised to play a central role in achieving demonstrable quantum advantage for molecular simulations with applications in drug development and materials science [2] [31].

The pursuit of quantum advantage in the Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) era has catalyzed the development of variational quantum algorithms that can dynamically adapt to specific problems. Among these, the Adaptive Derivative-Assembled Problem-Tailored Variational Quantum Eigensolver (ADAPT-VQE) has emerged as a promising approach for electronic structure calculations, particularly for quantum chemistry applications. The core innovation of ADAPT-VQE lies in its iterative construction of ansätze tailored to both the molecular Hamiltonian and the evolving variational state, a significant departure from fixed-structure ansätze like Unitary Coupled Cluster (UCC). The performance and efficiency of this algorithm critically depend on the design of the operator pool from which ansätze components are selected [2].