Resilient Quantum Measurement Protocols for Accurate Chemical Hamiltonian Simulation

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on advanced measurement strategies for quantum simulation of chemical systems.

Resilient Quantum Measurement Protocols for Accurate Chemical Hamiltonian Simulation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on advanced measurement strategies for quantum simulation of chemical systems. It explores the foundational challenges of measuring non-commuting observables in molecular Hamiltonians and details cutting-edge protocols that offer enhanced noise resilience and resource efficiency. Covering both theoretical frameworks and practical implementations, the content examines joint measurement strategies, noise mitigation techniques, and optimization methods tailored for near-term quantum hardware. Through comparative analysis and validation benchmarks on molecular systems, we demonstrate how these resilient protocols enable more accurate ground state energy estimation—a critical capability for computational drug discovery and materials design.

The Quantum Measurement Challenge in Computational Chemistry

Theoretical Foundations

Fermionic Operators and Second Quantization

In quantum chemistry and condensed matter physics, fermionic systems are described using creation ((c^\dagger)) and annihilation ((c)) operators that satisfy the anticommutation relations: (c^\dagger c + cc^\dagger = 1) and (c^2=0), ((c^\dagger)^2=0) [1]. These operators act on quantum states representing occupied ((\left|1\right\rangle)) and unoccupied ((\left|0\right\rangle)) fermionic modes. The electronic structure Hamiltonian in second quantization takes the general form [2]: [H = -\mu\sumn cn^\dagger cn - t\sumn (c{n+1}^\dagger cn + \textrm{h.c.}) + \Delta\sumn (cn c_{n+1} + \textrm{h.c.})] where (\mu) represents the onsite energy, (t) the hopping amplitude between sites, and (\Delta) the superconducting pairing potential.

Majorana Fermion Operators

Majorana operators provide an alternative representation defined as [1] [3]: [\gamma1 = c^\dagger + c,\quad \gamma2 = i(c^\dagger - c)] These operators are Hermitian ((\gammai = \gammai^\dagger)) and satisfy the anticommutation relations [1]: [\gamma1\gamma2 + \gamma2\gamma1 = 0,\quad \gamma1^2=1,\quad \gamma2^2=1] A single regular fermion can always be expressed using two Majorana operators, analogous to representing a complex number using two real numbers [1] [4]. In particle physics, Majorana fermions are hypothetical particles that are their own antiparticles, while in condensed matter systems, they emerge as quasiparticle excitations in superconducting materials [3].

Quantum Chemical Hamiltonians and Measurement Challenges

Electronic Structure Problem

The electronic structure Hamiltonian for quantum chemistry applications can be expressed in terms of Majorana operators [2] [5]: [H = U0\left(\sump gp np\right)U0^\dagger + \sum{\ell=1}^L U\ell\left(\sum{pq} g{pq}^{(\ell)} np nq\right)U\ell^\dagger] where (np = ap^\dagger ap) is the number operator, (gp) and (g{pq}^{(\ell)}) are scalar coefficients, and (U\ell) are unitary basis transformation operators.

Measurement Bottleneck in Variational Quantum Algorithms

The variational quantum eigensolver (VQE) framework uses quantum devices to prepare parameterized wavefunctions and measure Hamiltonian expectation values [2]. The required number of measurements (M) for estimating the expectation value (\langle H\rangle = \sum\ell \omega\ell \langle P\ell\rangle) to precision (\epsilon) is bounded by [2]: [M \le \left(\frac{\sum\ell |\omega\ell|}{\epsilon}\right)^2] where (P\ell) are Pauli words obtained by mapping fermionic operators to qubit operators via transformations such as Jordan-Wigner. For large molecules, this bound suggests an "astronomically large" number of measurements [2]. The Jordan-Wigner transformation further exacerbates this challenge by mapping fermionic operators to non-local qubit operators with support on up to all (N) qubits [2].

Table 1: Comparison of Measurement Strategies for Fermionic Hamiltonians

| Strategy | Term Groupings | Key Innovation | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Naive | (O(N^4)) | Independent measurement of all Pauli terms | Prohibitively expensive for large systems |

| Basis Rotation Grouping [2] | (O(N)) | Hamiltonian factorization and basis rotations | Requires linear-depth circuits |

| Joint Measurement [5] | (O(N^2\log(N)/\epsilon^2)) (quartic) | Joint measurement of Majorana pairs and quadruples | Optimized for 2D qubit layouts |

| Fermionic Classical Shadows [5] | (O(N^2\log(N)/\epsilon^2)) (quartic) | Randomized measurements and classical post-processing | Requires depth (O(N)) |

Resilient Measurement Protocols

Basis Rotation Grouping Protocol

This approach leverages tensor factorization techniques to dramatically reduce measurement costs [2]:

Protocol Steps:

- Hamiltonian Factorization: Express the Hamiltonian in the factorized form: [H = U0\left(\sump gp np\right)U0^\dagger + \sum{\ell=1}^L U\ell\left(\sum{pq} g{pq}^{(\ell)} np nq\right)U\ell^\dagger] using density fitting approximation or eigen-decomposition of the two-electron integral tensor [2].

Basis Transformation: Apply the unitary circuit (U_\ell) to the quantum state prior to measurement.

Occupation Number Measurement: Simultaneously sample all (\langle np\rangle) and (\langle np n_q\rangle) expectation values in the rotated basis.

Energy Estimation: Reconstruct the energy expectation value as: [\langle H\rangle = \sump gp \langle np\rangle0 + \sum{\ell=1}^L \sum{pq} g{pq}^{(\ell)} \langle np nq\rangle\ell]

This strategy provides a cubic reduction in term groupings over prior state-of-the-art and enables measurement times three orders of magnitude smaller for large systems [2].

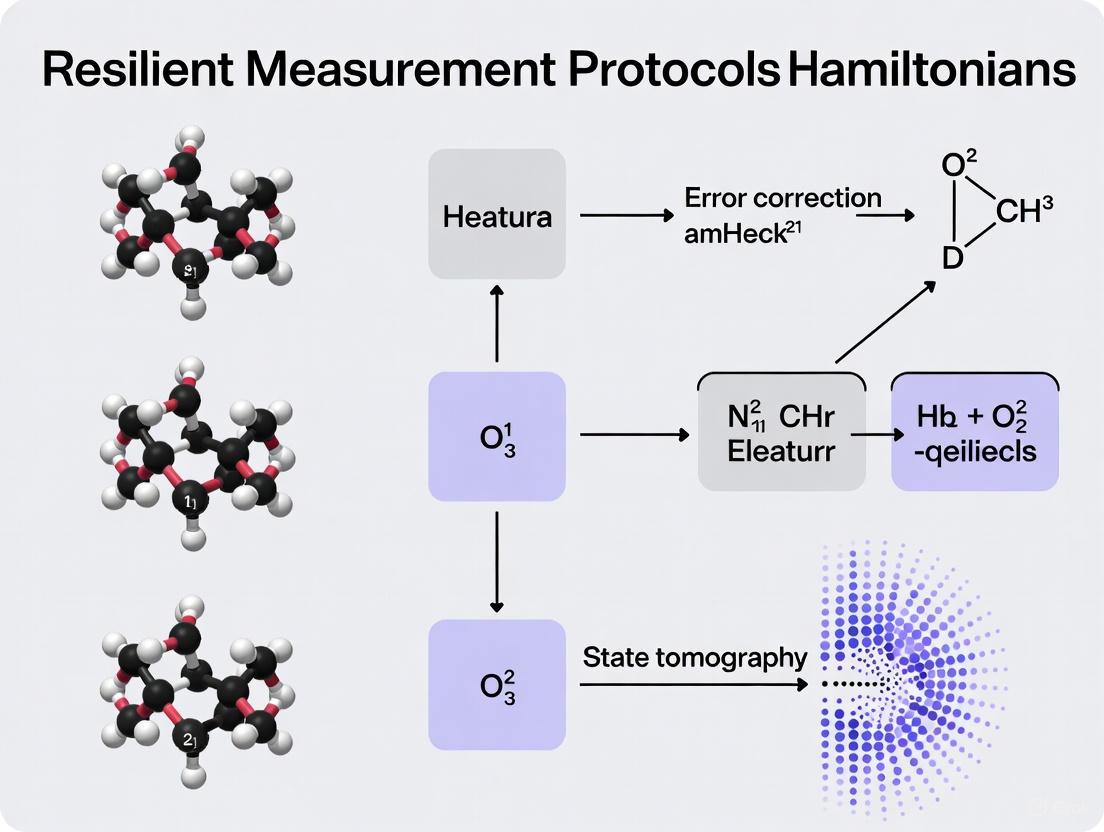

Figure 1: Basis Rotation Grouping Workflow

Joint Measurement Strategy for Majorana Operators

This recently developed protocol enables efficient estimation of fermionic observables by jointly measuring Majorana operators [5]:

Protocol Steps:

- Unitary Randomization: Sample from two distinct subsets of unitaries:

- Unitaries realizing products of Majorana operators

- Fermionic Gaussian unitaries that rotate disjoint blocks of Majorana operators

Occupation Number Measurement: Measure fermionic occupation numbers after unitary application.

Classical Post-processing: Process measurement outcomes to estimate expectation values of all quadratic and quartic Majorana monomials.

For a system with (N) fermionic modes, this approach estimates expectation values of quartic Majorana monomials to precision (\epsilon) using (\mathcal{O}(N^2\log(N)/\epsilon^2)) measurement rounds, matching the performance of fermionic classical shadows while offering advantages in circuit depth and error resilience [5].

Error Resilience and Symmetry Verification

These measurement strategies incorporate inherent error resilience:

Reduced Operator Support: Under Jordan-Wigner transformation, expectation values of Majorana pairs and quadruples are estimated from single-qubit measurements of one and two qubits respectively, limiting error propagation [5].

Symmetry Verification: The structure enables post-selection on proper eigenvalues of particle number (\eta) and spin (S_z) operators, allowing suppression of errors that violate symmetry constraints [2].

Error Mitigation Compatibility: The local nature of measurements facilitates integration with randomized error mitigation techniques such as zero-noise extrapolation [5].

Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 2: Essential Research Tools for Fermionic Hamiltonian Simulation

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| HamLib [6] | Software Library | Provides benchmark Hamiltonians (2-1000 qubits) | Algorithm development and validation |

| F_utilities [7] | Julia Package | Numerical manipulation of fermionic Gaussian systems | Prototyping and simulation |

| Fermionic Gaussian Unitaries | Mathematical Tool | Basis rotation for measurement grouping | Joint measurement protocols |

| Jordan-Wigner Transformation | Encoding Scheme | Maps fermionic operators to qubit operators | Quantum circuit implementation |

Implementation and Benchmarking

Quantum Circuit Implementation

For a rectangular lattice of qubits encoding an (N)-mode fermionic system via Jordan-Wigner transformation, the joint measurement strategy can be implemented with circuit depth (\mathcal{O}(N^{1/2})) using (\mathcal{O}(N^{3/2})) two-qubit gates [5]. This offers significant improvement over fermionic classical shadows that require depth (\mathcal{O}(N)) and (\mathcal{O}(N^2)) two-qubit gates.

Figure 2: Joint Measurement Protocol Architecture

Performance Benchmarking

Numerical benchmarks on exemplary molecular Hamiltonians demonstrate that these advanced measurement strategies achieve sample complexities comparable to state-of-the-art approaches while offering advantages in implementation overhead and error resilience [5]. The joint measurement strategy particularly excels for quantum chemistry applications where it can be implemented with only four distinct fermionic Gaussian unitaries [5].

The development of efficient and resilient measurement protocols for fermionic Hamiltonians represents a critical advancement for practical quantum computational chemistry. By leveraging mathematical structures of fermionic systems and Majorana operators, these protocols address the key bottleneck of measurement overhead in variational quantum algorithms. The integration of Hamiltonian factorization, strategic basis rotations, and joint measurement strategies enables characterization of complex molecular systems with significantly reduced resource requirements. Future research directions include adapting these protocols for emerging quantum processor architectures, developing more sophisticated error mitigation techniques specifically tailored for fermionic measurements, and extending these approaches to dynamical correlation functions and excited state calculations.

The Problem of Non-Commuting Observables in Molecular Systems

In quantum mechanics, non-commuting observables represent physical quantities that cannot be simultaneously measured with arbitrary precision. This fundamental limitation is mathematically expressed by the non-vanishing commutator of their corresponding operators. For two observables A and B, if their commutator [A,B] = AB - BA ≠0, then they do not commute [8]. In molecular systems, this phenomenon manifests most prominently in the inability to simultaneously determine key properties like position and momentum with perfect accuracy, fundamentally limiting the precision attainable in quantum chemical computations.

The core of the problem lies in the mathematical structure of quantum theory itself. When two operators do not commute, they cannot share a complete set of eigenvectors [9]. Consequently, a quantum state cannot simultaneously be in a definite state for both observables. This has profound implications for estimating molecular Hamiltonians, where the inability to simultaneously measure non-commuting observables significantly increases the measurement resource requirements and complicates the determination of molecular properties and reaction mechanisms.

Mathematical Framework and Theoretical Foundations

The commutator relationship for spin operators provides an illustrative example of non-commuting observables. For spin-½ systems, the operators for different spin components satisfy the commutation relation [Ŝₓ, Ŝy] = iħŜz, with analogous cyclic permutations [8]. This mathematical structure directly implies that a system cannot simultaneously have definite values for the x and y components of spin, embodying the uncertainty principle in a discrete quantum system.

For molecular Hamiltonians, which typically consist of sums of non-commuting fermionic operators, the measurement challenge becomes particularly acute. The Hamiltonian H for an N-mode fermionic system can be expressed as:

H = Σ{A⊆[2N]} hA γ_A

where γA represents Majorana monomials of degree |A|, and hA are real coefficients [5]. These Majorana operators are fermionic analogs of quadratures and are defined as γ{2i-1} = ai + ai^†and γ{2i} = i(ai^†- ai), where ai^†and ai are fermionic creation and annihilation operators satisfying the canonical anticommutation relations [5]. The non-commutativity of these operators presents a fundamental obstacle to efficient Hamiltonian estimation.

Measurement Strategies for Non-Commuting Observables

Comparative Analysis of Measurement Approaches

Table 1: Strategies for measuring non-commuting observables in molecular systems

| Strategy | Key Principle | Advantages | Limitations | Resource Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commuting Grouping [5] | Partitioning observables into mutually commuting sets | Simplified measurement; Classical post-processing | May require many measurement rounds; Grouping is NP-hard | Scales with number of groups; Polynomial classical overhead |

| Classical Shadows [5] | Randomized measurements to construct classical state representation | Simultaneous estimation of multiple observables | Requires random unitary implementations | ${\mathcal{O}}(N\log(N)/{\epsilon}^{2})$ rounds for precision $\epsilon$ |

| Joint Measurements [5] | Measurement of noisy versions of non-commuting observables | Direct simultaneous measurement; Constant-depth circuits | Introduces measurement noise | ${\mathcal{O}}(N^{2}\log(N)/{\epsilon}^{2})$ rounds for quartic terms |

| Weak Measurements [10] | Minimal perturbation to system with partial information extraction | Bypasses uncertainty principle; Continuous monitoring | Low-information gain per measurement; Complex implementation | Large repetition counts for precision |

Joint Measurement Protocol for Fermionic Systems

Recent advances have demonstrated that a carefully designed joint measurement strategy can efficiently estimate non-commuting fermionic observables. The protocol involves the following key steps [5]:

Unitary Preparation: Apply a unitary transformation U sampled from a carefully constructed set of fermionic Gaussian unitaries. For quadratic and quartic Majorana monomials, sets of two or nine fermionic Gaussian unitaries are sufficient to jointly measure all noisy versions of the desired observables.

Occupation Number Measurement: Measure the fermionic occupation numbers in the transformed basis.

Classical Post-processing: Process the measurement outcomes to extract estimates of the expectation values of the target observables.

For quantum chemistry Hamiltonians specifically, the measurement strategy can be optimized such that only four fermionic Gaussian unitaries in the second subset are sufficient [5]. This approach estimates expectation values of all quadratic and quartic Majorana monomials to precision ε using ${\mathcal{O}}(N\log(N)/{\epsilon}^{2})$ and ${\mathcal{O}}(N^{2}\log(N)/{\epsilon}^{2})$ measurement rounds, respectively, matching the performance guarantees of fermionic classical shadows while offering potential advantages in implementation depth.

Quantum-Classical Hybrid Approaches

The Observable Dynamic Mode Decomposition (ODMD) method represents a recent innovation in quantum-classical hybrid algorithms for eigenenergy estimation [11]. This approach collects real-time measurements and processes them using dynamic mode decomposition, functioning as a stable variational method on the function space of observables available from a quantum many-body system. The method demonstrates rapid convergence even in the presence of significant perturbative noise, making it particularly suitable for near-term quantum hardware with inherent noise limitations.

Experimental Protocol: Joint Measurement Implementation

Resource Requirements and Experimental Setup

Table 2: Research reagent solutions for joint measurement experiments

| Component | Specification | Function | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fermionic Gaussian Unitaries | Set of 2 (quadratic) or 9 (quartic) unitaries | Rotation into measurable basis | Implemented via Givens rotations or matchgate circuits |

| Occupation Number Measurement | Projective measurement in computational basis | Extracts occupation information | Standard Pauli Z measurements after Jordan-Wigner |

| Classical Post-processing | Statistical estimation algorithms | Derives observable expectations | Linear algebra with ${\mathcal{O}}(N^2)$ complexity |

| Error Mitigation | Randomized compiling or zero-noise extrapolation | Reduces device noise impacts | Additional 2-5x overhead in circuit repetitions |

Step-by-Step Protocol

Phase 1: Pre-measurement Preparation

Hamiltonian Decomposition: Express the target molecular Hamiltonian H in terms of Majorana monomials: H = Σ{A⊆[2N]} hA γ_A.

Unitary Selection: For the target observables (quadratic or quartic Majorana monomials), select the appropriate set of fermionic Gaussian unitaries from the predetermined collection.

Circuit Compilation: Compile each selected fermionic Gaussian unitary into gate-level operations appropriate for the target quantum processor, using either the Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev transformation.

Phase 2: Quantum Execution

State Preparation: Initialize the quantum processor in the desired molecular state |ψ⟩.

Unitary Application: Apply the selected fermionic Gaussian unitary U to the prepared state: |ψ_U⟩ = U|ψ⟩.

Measurement: Perform occupation number measurements on the transformed state |ψ_U⟩ in the computational basis.

Repetition: Repeat steps 4-6 for a sufficient number of shots to achieve the desired statistical precision for all target observables.

Unitary Iteration: Repeat steps 5-7 for all unitaries in the selected set.

Phase 3: Classical Processing

Data Aggregation: Collect all measurement outcomes across different unitary applications.

Estimation: Apply the appropriate classical post-processing algorithm to compute estimates ⟨γ_A⟩ for all target Majorana monomials.

Hamiltonian Estimation: Reconstruct the Hamiltonian expectation value as ⟨H⟩ = Σ{A⊆[2N]} hA ⟨γ_A⟩.

Implementation Considerations for Quantum Hardware

Under the Jordan-Wigner transformation on a rectangular qubit lattice, the joint measurement circuit can be implemented with depth ${\mathcal{O}}(N^{1/2})$ using ${\mathcal{O}}(N^{3/2})$ two-qubit gates [5]. This offers a significant improvement over fermionic and matchgate classical shadows that require depth ${\mathcal{O}}(N)$ and ${\mathcal{O}}(N^{2})$ two-qubit gates respectively. The expectation values of Majorana pairs and quadruples can be estimated from single-qubit measurement outcomes of one and two qubits respectively, which means each estimate is affected only by errors on at most two qubits, making the strategy amenable to error mitigation techniques.

Applications in Molecular Systems and Drug Development

For drug development professionals, efficient measurement of non-commuting observables enables more accurate prediction of molecular properties critical to pharmaceutical design. The ability to reliably estimate molecular Hamiltonian energies with reduced quantum resources directly impacts:

- Reaction Mechanism Elucidation: More efficient determination of transition states and reaction pathways.

- Binding Affinity Prediction: Improved accuracy in calculating protein-ligand interaction energies.

- Electronic Structure Determination: Enhanced capability for predicting molecular spectra and properties.

- Drug Candidate Screening: Accelerated virtual screening through more efficient quantum computations.

The joint measurement approach demonstrates particular value for electronic structure Hamiltonians where it can be specifically optimized, requiring only four fermionic Gaussian unitaries while maintaining favorable scaling in measurement rounds and circuit depth [5].

The problem of non-commuting observables in molecular systems presents both a fundamental challenge and an opportunity for algorithmic innovation. Recent developments in joint measurement strategies, classical shadows, and quantum-classical hybrid approaches have significantly advanced our ability to efficiently estimate molecular Hamiltonians despite the fundamental limitations imposed by non-commutativity.

As quantum hardware continues to evolve, these measurement strategies will play an increasingly crucial role in enabling practical quantum chemistry simulations on quantum processors. The integration of resilient measurement protocols with error mitigation techniques represents a promising direction for extracting useful chemical information from near-term quantum devices, potentially accelerating drug discovery and materials design through more accurate and efficient quantum chemical computations.

{# Foundations of Joint Measurement Strategies}

:::{.info} Document Scope: This document outlines the foundational principles and practical protocols for joint measurement strategies, with a specific focus on their application in variational quantum eigensolver (VQE) algorithms for estimating quantum chemical Hamiltonians. The content is designed for researchers and scientists engaged in the development of noise-resilient quantum computational methods for drug discovery and materials design. :::

The accurate estimation of molecular energies is a cornerstone of computational chemistry and drug development. On near-term quantum devices, this is often attempted using the VQE. A primary bottleneck in this process is the measurement of the molecular Hamiltonian, ( H ), which is a sum of many non-commuting observables. Traditional methods measure these observables in separate, mutually exclusive experimental settings, leading to a significant overhead in the number of state preparations and measurements required.

Joint measurement strategies present a paradigm shift. Instead of measuring each observable perfectly but separately, these strategies perform a single, sophisticated measurement on the quantum state, from which the expectation values of multiple non-commuting observables can be simultaneously inferred through classical post-processing [12] [13]. This approach is foundational for developing resilient measurement protocols, as it can offer a dramatic reduction in the required number of measurement rounds and can be inherently more robust to certain types of noise.

Core Principles and Theoretical Foundations

A joint measurement is a single Positive Operator-Valued Measure (POVM) whose outcome statistics can be used to compute the expectation values of a set of target observables ({\hat{O}_i}). The key idea is that the POVM elements are constructed such that they provide a noisy or "unsharp" version of the original observables [12] [13]. For a set of fermionic observables, which are typically products of Majorana operators, this involves:

- Randomization: Applying a unitary (U_k), randomly sampled from a carefully chosen set, to the quantum state (|\psi\rangle).

- Projective Measurement: Performing a standard measurement (e.g., of fermionic occupation numbers) in the rotated basis.

- Post-processing: Using the classical outcomes and knowledge of (U_k) to compute estimates for the target observables.

This procedure effectively implements a joint measurement of a set of compatible, noisy versions of the original non-commuting observables. The variance of the resulting estimators dictates the sample complexity—the number of experimental repetitions needed to achieve a desired precision.

Performance Specifications and Comparative Analysis

The following table summarizes the performance of key joint measurement strategies against other state-of-the-art techniques for molecular Hamiltonian estimation.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Measurement Strategies for Quantum Chemistry

| Strategy | Sample Complexity Scaling | Key Experimental Considerations | Key Advantages | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Joint Measurement (Majorana) [12] | (\mathcal{O}(\frac{N^2 \log N}{\epsilon^2})) for quartic terms | Circuit depth: (\mathcal{O}(N^{1/2})) on 2D lattice. Two-qubit gates: (\mathcal{O}(N^{3/2})). | Matches sample complexity of fermionic shadows with lower circuit depth. Resilient to errors on at most 2 qubits per estimate. | ||

| Basis Rotation Grouping (Low-Rank) [2] [14] | (M \le \left(\frac{\sum_{\ell} | \omega_{\ell} | }{\epsilon}\right)^2) (Empirically, 3 orders of magnitude reduction vs. bounds) | Requires a linear-depth circuit ((U_{\ell})) prior to measurement. | Cubic reduction in term groupings. Enables post-selection on particle number/spin, providing powerful error mitigation. |

| Classical Shadows (Fermionic) [12] | (\mathcal{O}(\frac{N^2 \log N}{\epsilon^2})) for quartic terms | Circuit depth: (\mathcal{O}(N)). Two-qubit gates: (\mathcal{O}(N^{2})). | Proven performance guarantees. A highly general and versatile framework. | ||

| Hamiltonian Averaging (Naive) [2] | (M \le \left(\frac{\sum_{\ell} | w_{\ell} | }{\epsilon}\right)^2) (Worst-case bound, leads to "astronomically large" M) | No special circuits, but a vast number of different measurement settings. | Simple to implement conceptually. |

Note: (N) refers to the number of fermionic modes/orbitals, and (\epsilon) is the target precision.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Joint Measurement of Majorana Operators

This protocol estimates expectation values of quadratic ((\gammai\gammaj)) and quartic ((\gammai\gammaj\gammak\gammal)) Majorana operators, which form the building blocks of molecular Hamiltonians under the Jordan-Wigner transformation [12].

Workflow Overview:

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- State Preparation: Prepare the fermionic quantum state (|\psi\rangle) on the quantum processor. This is typically the output of a parameterized quantum circuit (ansatz) in a VQE.

- Random Unitary Selection:

- For a system of (N) modes, sample a unitary (U_k) uniformly from a set of fermionic Gaussian unitaries. The set is designed such that its elements rotate disjoint blocks of Majorana operators.

- For quartic monomials, a set of nine specific fermionic Gaussian unitaries is sufficient to jointly measure all noisy versions of the observables [12].

- Circuit Execution: Apply the selected (U_k) to the state (|\psi\rangle).

- Projective Measurement: Perform a measurement in the computational basis to obtain a bitstring representing the occupation numbers ((n1, n2, ..., n_N)).

- Classical Post-processing:

- For each target Majorana monomial (e.g., (\gammai\gammaj\gammak\gammal)), apply a pre-computed classical function to the measured bitstring and the index (k) of the chosen unitary.

- This function outputs an unbiased estimate for the expectation value of that monomial.

- The estimates for all monomials are produced from the same measurement outcome.

- Averaging: Repeat steps 2-5 for a sufficient number of rounds ((R)) and average the estimates for each observable to reduce statistical error.

Protocol 2: Basis Rotation Grouping via Hamiltonian Factorization

This strategy leverages a low-rank factorization of the two-electron integral tensor to drastically reduce the number of unique measurement settings [2] [14].

Workflow Overview:

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Classical Hamiltonian Factorization:

- Perform a double factorization of the electronic structure Hamiltonian. This yields a representation of the form: ( H = U0 (\sump gp np) U0^\dagger + \sum{\ell=1}^L U\ell (\sum{pq} g{pq}^{(\ell)} np nq) U\ell^\dagger ) where (U\ell) are basis rotation unitaries, and (gp), (g_{pq}^{(\ell)}) are scalars [2] [14].

- The number of terms (L) scales linearly with the number of orbitals (N).

- State Preparation: Prepare the fermionic state (|\psi\rangle).

- Iterative Measurement for Each Group:

- For each (\ell) from 0 to (L): a. Basis Rotation: Apply the unitary (U\ell) to the state (|\psi\rangle). b. Simultaneous Measurement: Measure the occupation number operator (np = ap^\dagger ap) for all orbitals (p). This is equivalent to a computational basis measurement under the Jordan-Wigner transformation. c. Data Collection: From the measured bitstrings, compute the expectation values (\langle np \rangle\ell) and (\langle np nq \rangle_\ell) for all (p) and (q).

- Energy Reconstruction:

- Classically combine the measured expectation values with the pre-computed coefficients (gp) and (g{pq}^{(\ell)}) to compute the total energy estimate: (\langle H \rangle = \sump gp \langle np \rangle0 + \sum{\ell=1}^L \sum{pq} g{pq}^{(\ell)} \langle np nq \rangle\ell).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Components for Implementing Joint Measurement Protocols

| Item / Concept | Function in the Protocol | Specification / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Fermionic Gaussian Unitaries | To randomize the measurement basis, enabling the joint measurement of non-commuting Majorana operators. | A constant-sized set (e.g., 2 for pairs, 9 for quadruples) is sufficient [12]. |

| Low-Rank Factorization | To reduce the Hamiltonian into a sum of few terms that are diagonal in a rotated basis. | Methods: Density Fitting, Cholesky, or Eigen decomposition of the two-electron integral tensor [2] [14]. |

| Jordan-Wigner Transformation | To map fermionic operators to qubit operators for execution on a qubit-based quantum processor. | Makes the measurement of (n_p) a single-qubit Z measurement. |

| Classical Post-Processor | To convert raw measurement outcomes into unbiased estimates of target observables. | Implements the estimator functions derived from the joint measurement theory [12]. |

| Error Mitigation via Post-selection | To filter out measurement outcomes that violate known physical constraints (e.g., particle number). | Enabled by measuring local operators (e.g., (n_p)) rather than non-local Pauli strings [2]. |

| AMG-076 free base | AMG-076 free base, CAS:693823-79-9, MF:C26H33F3N2O2, MW:462.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Amfonelic Acid | Amfonelic Acid, CAS:15180-02-6, MF:C18H16N2O3, MW:308.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Accurately measuring the energy of quantum chemical Hamiltonians is a cornerstone for applying quantum computing to fields like drug development and materials science. On near-term quantum devices, the inherent noise, finite sampling statistics, and resource limitations pose significant challenges to obtaining reliable, high-precision results. This document outlines the key performance metrics—precision, sample complexity, and resource requirements—that are critical for evaluating and developing resilient measurement protocols. It provides a comparative analysis of state-of-the-art techniques, detailed experimental protocols for their implementation, and visual guides to their workflows, serving as a practical resource for researchers aiming to optimize quantum computations for chemistry.

Performance Metrics Comparison

The performance of different measurement strategies can be quantified through their sample complexity, achievable precision, and quantum resource overhead. The following table summarizes these metrics for several prominent techniques.

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics of Quantum Measurement Strategies

| Method (Citation) | Reported Precision (Hartree) | Sample Complexity / Shot Count | Key Quantum Resource Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| State-Specific Measurement [15] | N/A | 30-80% reduction vs. state-of-the-art | Reduced circuit depth for measurement; uses Hard-Core Bosonic (HCB) grouping. |

| Locally Biased Shadows & QDT [16] | 0.0016 (Chemical Precision) | Not specified | Mitigates readout errors via Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT); requires execution of calibration circuits. |

| Joint Measurement Strategy [5] | N/A | $\mathcal{O}(N^2 \log(N)/\epsilon^{2})$ for quartic terms | Circuit depth: $\mathcal{O}(N^{1/2})$; $\mathcal{O}(N^{3/2})$ two-qubit gates on a 2D lattice. |

| Empirical Bernstein Stopping (EBS) [17] | N/A | Up to 10x improvement over worst-case guarantees | Adaptive shot allocation based on empirical variance; requires classical processing during data collection. |

| Qubitization QPE (First-Quantized) [18] | Chemical Accuracy | ~$10^8$-$10^{12}$ Toffoli gates for a 72-electron molecule | High logical qubit count and T-gate complexity; suited for fault-tolerant era. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

This section provides step-by-step methodologies for implementing two key measurement strategies: one designed for near-term devices and another for the fault-tolerant future.

Protocol for State-Specific Measurement in VQE

This protocol, adapted from Bincoletto and Kottmann, reduces measurement overhead in the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) by leveraging the structure of the prepared quantum state and the Hamiltonian [15].

1. Hamiltonian Preparation:

- Begin with the electronic Hamiltonian in second quantization.

- Transform it into a qubit Hamiltonian using a fermion-to-qubit mapping (e.g., Jordan-Wigner), expressing it as a sum of Pauli strings: ( H = \sumi wi P_i ) [15] [19].

2. Initial Cheap Measurement:

- Identify a set of "cheap" Pauli operators, for instance, those belonging to three self-commuting groups defined by the Hard-Core Bosonic (HCB) approximation. These groups can be measured simultaneously with minimal circuit depth [15].

- Perform an initial measurement of these cheap operators on the prepared variational state ( |\Psi(\theta)\rangle ) to compute a preliminary approximation of the energy expectation value.

3. Iterative Residual Estimation:

- The residual energy is the difference between the true energy and the initial approximation. To estimate it, new grouped operators (beyond the initial cheap set) are iteratively measured in different bases.

- In each iteration, select the most significant remaining Pauli terms, group them into commuting cliques, and measure them. Update the energy estimate with the new results.

- Truncate the process after a predefined number of iterations or when the residual energy contribution falls below a desired threshold. This step provides a tunable trade-off between measurement effort and accuracy [15].

Protocol for Fault-Tolerant Energy Estimation via Qubitization

This protocol outlines the process for performing high-accuracy ground state energy estimation using Quantum Phase Estimation (QPE) and the qubitization technique, which is suitable for fault-tolerant quantum computers [20] [18].

1. System Encoding and Hamiltonian Block Encoding:

- Select a Basis Set: Choose a basis set (e.g., plane-wave or molecular orbitals) to represent the electronic structure problem. Plane-wave bases in first quantization can offer favorable scaling for large systems [18].

- Construct the Qubitization Operator: The Hamiltonian ( H ) is first expressed as a linear combination of unitaries: ( H = \sumk \alphak Vk ). Then, a unitary qubitization operator ( Q ) is constructed, which block-encodes the Hamiltonian in a larger subspace. The eigenvalues of ( Q ) are directly related to the eigenvalues of ( H ) via ( e^{\pm i \arccos(Ej / \lambda)} ), where ( \lambda = \sumk \alphak ) [20].

2. Initial State Preparation:

- Prepare an initial state ( |\Phi\rangle ) that has a non-negligible overlap with the true ground state. Methods like Hartree-Fock are commonly used to generate such states efficiently [20].

3. Quantum Phase Estimation (QPE):

- Use the QPE algorithm with the qubitization operator ( Q ) as the unitary input.

- QPE will, with high probability, collapse the system register to the ground state and yield a binary representation of the phase ( \arccos(E_0 / \lambda) ) on an output register of phase-estimation qubits.

- Perform the inverse cosine function classically to retrieve the ground-state energy ( E_0 ) from the measured phase [20].

4. Resource Estimation:

- The total cost is dominated by the number of calls to the qubitization operator ( Q ), which scales as ( O(\lambda / \varepsilon) ) for a target precision ( \varepsilon ) [20].

- For a system with ( N ) electrons and ( M ) orbitals, the gate cost of first-quantized qubitization can scale as ( \tilde{O}((N^{4/3}M^{2/3} + N^{8/3}M^{1/3})/\varepsilon) ) [18].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagrams illustrate the logical flow of the two protocols described above, highlighting their adaptive and iterative nature.

Diagram 1: State-specific adaptive VQE measurement protocol, showing the iterative process of measuring cheap operators first and then refining the estimate by targeting significant residual terms [15].

Diagram 2: Fault-tolerant energy estimation via qubitization and QPE, showing the sequence from system encoding to classical extraction of the energy value [20] [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit

This section details the essential "research reagents"—the core algorithmic components and techniques—required to implement resilient measurement protocols for quantum chemical Hamiltonians.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Quantum Measurement

| Research Reagent | Function & Purpose | Key Variants / Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Fermion-to-Qubit Mapping | Transforms the fermionic Hamiltonian of a molecule into a qubit Hamiltonian composed of Pauli operators. | Jordan-Wigner, Bravyi-Kitaev [15] [19] |

| Measurement Grouping | Reduces the number of distinct quantum circuit executions (shot overhead) by grouping commuting Pauli terms that can be measured simultaneously. | Qubit-wise Commuting (QWC), Fully Commuting (FC), Fermionic-algebra-based (e.g., F3, LR) [15] [19] |

| Readout Error Mitigation | Corrects for inaccuracies introduced during the final measurement of qubits, a dominant noise source on near-term devices. | Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT), Randomized Error Mitigation [16] [5] |

| Adaptive Shot Allocation | Dynamically distributes a limited shot budget across Hamiltonian terms to minimize the overall statistical error, leveraging variance information. | Empirical Bernstein Stopping (EBS), Locally Biased Random Measurements [16] [17] |

| Block Encoding / Qubitization | A fault-tolerant primitive that embeds a Hamiltonian into a subspace of a larger unitary operator, enabling efficient energy estimation via QPE. | Qubitization, Linear Combination of Unitaries (LCU) [20] [18] |

| Anilofos | Anilofos, CAS:64249-01-0, MF:C13H19ClNO3PS2, MW:367.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Anpirtoline | Anpirtoline, CAS:98330-05-3, MF:C10H13ClN2S, MW:228.74 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Advanced Protocols for Noise-Resilient Hamiltonian Estimation

Joint Measurement Strategies for Fermionic Observables

Estimating the properties of fermionic quantum systems is a fundamental task in quantum chemistry, with direct applications in drug discovery and materials science. A significant challenge in this domain is the efficient measurement of non-commuting observables that constitute molecular Hamiltonians, a process often hampered by the inherent limitations of near-term quantum devices. This article details joint measurement strategies, which provide a resource-efficient framework for estimating fermionic observables by enabling the simultaneous measurement of multiple non-commuting operators. These strategies are a cornerstone for developing resilient measurement protocols essential for accurate quantum simulations of chemical systems on noisy hardware. By reducing the circuit depth and the number of distinct measurement rounds required, these methods pave the way for the practical application of variational quantum algorithms to complex molecules relevant to pharmaceutical research.

Background and Core Concepts

Fermionic Systems and Majorana Observables

In quantum chemistry, the electronic structure problem is typically encoded in an N-mode fermionic system. The system's Fock space is spanned by occupation number vectors |nâ‚, nâ‚‚, ..., nₙ⟩, where náµ¢ ∈ {0,1} [5]. For simulation and measurement, it is often convenient to use the Majorana representation, which introduces 2N* Hermitian operators, γâ‚, γ₂, ..., γ₂ₙ, defined in terms of the standard creation (aᵢ†) and annihilation (aáµ¢) operators [5]:

- γ₂ᵢ₋₠= aáµ¢ + aáµ¢â€

- γ₂ᵢ = i(aᵢ†- aᵢ)

These Majorana operators satisfy the anticommutation relation {γᵢ, γⱼ} = 2δᵢⱼð•€. Products of these operators, known as Majorana monomials, are central to the formulation of fermionic Hamiltonians. For an even-sized subset A ⊂ [2N], the corresponding monomial is defined as γA = i^|A|/² âˆ{i∈A} γ_i. Molecular Hamiltonians encountered in quantum chemistry are primarily composed of quadratic (pairs) and quartic (quadruples) Majorana monomials, which correspond to one- and two-electron interactions, respectively [5] [21].

The Challenge of Non-Commuting Observables

A primary bottleneck in estimating the energy of a molecular Hamiltonian on a quantum computer is the non-commutativity of its constituent terms. Conventional approaches require measuring each group of commuting observables in a separate experiment, leading to a large number of state preparation and measurement rounds. This measurement overhead can become prohibitive for large molecules, limiting the practical utility of near-term quantum algorithms. Joint measurability addresses this challenge by providing a framework for designing a single quantum measurement whose outcomes can be classically post-processed to simultaneously estimate the expectation values of multiple non-commuting observables [5] [22]. This is achieved by constructing a parent measurement that effectively performs a noisy version of each target observable, thereby circumventing the fundamental restrictions imposed by non-commutativity [22].

Core Protocol for Fermionic Joint Measurement

The joint measurement strategy provides a streamlined process for estimating expectation values of all quadratic and quartic Majorana observables with provable performance guarantees. The core protocol involves a two-stage randomization process followed by occupation number measurement and classical post-processing [5] [21].

Step-by-Step Protocol Workflow

The following workflow outlines the sequential and parallel stages of the joint measurement protocol, from initialization to final estimation:

Step 1: State Preparation Prepare the fermionic state Ï of interest on the quantum processor. This could be, for example, an ansatz state generated by a Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) algorithm for a target molecule.

Step 2: First Randomization - Majorana Operator Products Sample and apply a unitary Uâ‚ from a predefined set that realizes products of Majorana fermion operators. This initial randomization is crucial for constructing the joint measurement [5] [21].

Step 3: Second Randomization - Fermionic Gaussian Unitaries Sample and apply a unitary Uâ‚‚ from a small, constant-sized set of suitably chosen fermionic Gaussian unitaries. For the estimation of all quartic Majorana observables, only nine such unitaries are sufficient. When specifically targeting electronic structure Hamiltonians, this requirement can be reduced to just four unitaries [5].

Step 4: Occupation Number Measurement Perform a projective measurement in the fermionic occupation number basis, yielding a bitstring (nâ‚, nâ‚‚, ..., nâ‚™) where each náµ¢ ∈ {0,1} [5].

Step 5: Classical Post-processing Process the measurement outcomes to compute unbiased estimators γ̂A for each Majorana monomial γA of interest. The information from a single experiment can be recycled to estimate multiple observables simultaneously [5].

Key Theoretical Performance Guarantees

This joint measurement strategy offers rigorous performance bounds that match state-of-the-art fermionic classical shadows while providing practical advantages in circuit implementation [5] [21].

Table 1: Performance Bounds for Fermionic Joint Measurement

| Observable Type | Sample Complexity | Circuit Depth (2D Lattice) | Two-Qubit Gates |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quadratic Majorana Monomials | ð“ž(N log(N)/ε²) | ð“ž(N¹/²) | ð“ž(N³/²) |

| Quartic Majorana Monomials | ð“ž(N² log(N)/ε²) | ð“ž(N¹/²) | ð“ž(N³/²) |

The sample complexity for estimating expectation values to precision ε matches the performance offered by fermionic classical shadows [5]. Under the Jordan-Wigner transformation on a rectangular qubit lattice, the measurement circuit achieves shallower depth compared to fermionic and matchgate classical shadows, which require depth ð“ž(N) and ð“ž(N²) with ð“ž(N²) two-qubit gates, respectively [5] [21]. Each estimate of Majorana pairs and quadruples is affected by errors on at most one and two qubits, respectively, making the strategy amenable to randomized error mitigation techniques [5].

Experimental Implementation and Optimization

Quantum Resource Requirements

The practical implementation of the joint measurement strategy requires careful consideration of quantum resources, which vary significantly with the system architecture and fermion-to-qubit mapping.

Table 2: Resource Requirements Across Different Qubit Layouts

| Implementation Factor | 2D Rectangular Lattice | All-to-All Connectivity | Heavy-Hex Lattice (IBM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Circuit Depth | ð“ž(N¹/²) | Constant depth possible [5] | Constant overhead to simulate rectangular lattice [5] |

| Two-Qubit Gate Count | ð“ž(N³/²) | Varies | Constant overhead |

| Key Advantage | Matches current superconducting processor architectures | Maximum theoretical efficiency | Direct implementation on IBM quantum systems |

For quantum chemistry applications, the strategy can be tailored specifically for electronic structure Hamiltonians, reducing the number of required fermionic Gaussian unitaries in the second randomization step from nine to four [5]. This optimization directly decreases the measurement overhead for pharmaceutical applications where molecular energy estimation is crucial.

Error Mitigation and Precision Enhancement

Achieving chemical precision (1.6×10â»Â³ Hartree) in molecular energy estimation requires integrating the joint measurement strategy with advanced error mitigation techniques:

- Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT): Implementing repeated measurement settings with parallel QDT significantly reduces readout errors. Experimental demonstrations on IBM quantum processors have shown error reduction from 1-5% to 0.16% using this approach [16].

- Locally Biased Random Measurements: This technique reduces shot overhead by prioritizing measurement settings that have a greater impact on the energy estimation, while maintaining the informationally complete nature of the measurement strategy [16].

- Blended Scheduling: Temporal variations in detector noise can be mitigated by interleaving circuits for different Hamiltonians and QDT, ensuring homogeneous noise distribution across all measurements [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Components for Fermionic Joint Measurement Experiments

| Component | Function | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Majorana Operators (γ_i) | Hermitian fermionic operators forming the basis for observables | Defined as γ₂ᵢ₋₠= aᵢ + aᵢ†, γ₂ᵢ = i(aᵢ†- aᵢ) [5] |

| Fermionic Gaussian Unitaries | Rotate disjoint blocks of Majorana operators into balanced superpositions | Constant-sized set sufficient (e.g., 9 for general quartics, 4 for molecular Hamiltonians) [5] |

| Occupation Number Measurement | Projective measurement in the fermionic mode basis | Yields bitstring (nâ‚, nâ‚‚, ..., nâ‚™) where náµ¢ ∈ {0,1} [5] |

| Jordan-Wigner Transformation | Maps fermionic operators to qubit operators | Enables implementation on quantum processors; preserves locality [5] |

| Classical Shadow Estimation | Post-processing technique for unbiased observable estimation | Recycles single experiment data for multiple observables [5] [16] |

| Antalarmin | Antalarmin, CAS:157284-96-3, MF:C24H34N4, MW:378.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Althiomycin | Althiomycin|Antibiotic|CAS 12656-40-5 |

Logical Relationships in the Measurement Framework

The conceptual foundation of the joint measurement strategy rests on the mathematical relationship between fundamental fermionic operations and their practical implementation on quantum hardware, as shown in the following logical framework:

Applications in Pharmaceutical Research

The joint measurement strategy for fermionic observables has significant implications for drug development, particularly in the accurate simulation of molecular systems that are classically intractable. Applications include:

- High-Throughput Virtual Screening: By reducing the quantum resource requirements for molecular energy estimation, the protocol enables more efficient screening of candidate drug molecules for binding affinity and stability.

- Reaction Mechanism Elucidation: Precise estimation of ground and excited state energies is essential for modeling reaction pathways in catalytic processes, including those involving transition metal complexes like iron-sulfur clusters found in biological systems [23].

- Photosensitizer Optimization: The protocol has been experimentally validated on molecules like BODIPY (Boron-dipyrromethene), an important class of organic fluorescent dyes used in photodynamic therapy, medical imaging, and biolabelling [16]. Accurate estimation of their excited state energies (Sâ‚€, Sâ‚, Tâ‚) is crucial for optimizing their therapeutic and diagnostic applications.

Joint measurement strategies for fermionic observables represent a significant advancement in the toolkit for quantum computational chemistry. By enabling efficient estimation of non-commuting observables with provable performance guarantees and reduced quantum resource requirements, these protocols address a critical bottleneck in the quantum simulation of molecular Hamiltonians. The integration of these strategies with robust error mitigation techniques paves the way for achieving chemical precision in molecular energy estimation on near-term quantum hardware. For researchers in pharmaceutical development, these advances offer a practical pathway toward leveraging quantum computing for drug discovery challenges, from virtual screening to the optimization of phototherapeutic agents.

The accurate estimation of quantum chemical Hamiltonians represents a central challenge in computational chemistry and drug development, with direct implications for predicting molecular properties, reaction mechanisms, and drug-target interactions. Traditional quantum simulation methods often face significant limitations, including prohibitive computational resource requirements and sensitivity to experimental noise. This has spurred the development of resilient measurement protocols that leverage hybrid quantum-classical frameworks to extract maximum information from minimal quantum resources. Two particularly powerful approaches have emerged at the forefront of this research: Dynamic Mode Decomposition (DMD), a time-series analysis technique adapted for quantum systems, and Classical Shadows, a randomized measurement strategy for efficient observable estimation. These measurement-driven approaches enable researchers to overcome the limitations of near-term quantum devices by combining targeted quantum measurements with advanced classical post-processing algorithms, creating a robust pipeline for molecular energy estimation even under noisy experimental conditions.

Theoretical Foundations

Dynamic Mode Decomposition for Quantum Systems

Dynamic Mode Decomposition is a dimensionality reduction algorithm originally developed in fluid dynamics that identifies coherent spatial structures and their temporal evolution from time-series data [24]. When applied to quantum systems, DMD functions as a Koopman operator approximation, analyzing the time evolution of observables to extract eigenenergies. The fundamental principle involves collecting a sequence of quantum state snapshots and then identifying the best-fit linear operator that advances the system's state forward in time. The eigenvalues of this operator then correspond directly to the system's eigenenergies.

The mathematical procedure for the SVD-based DMD algorithm is as follows [24]:

- Snapshot Collection: A time series of data is split into two overlapping sequences: ( V1^{N-1} = {v1, v2, \dots, v{N-1}} ) and ( V2^{N} = {v2, v3, \dots, vN} ), where each ( v_i ) represents a quantum measurement snapshot.

- Singular Value Decomposition (SVD): The matrix ( V1^{N-1} ) is decomposed as ( V1^{N-1} = U \Sigma W^T ), providing a low-rank approximation of the system dynamics.

- Operator Identification: A low-dimensional representation of the Koopman operator is constructed as ( \tilde{S} = U^T V_2^{N} W \Sigma^{-1} ).

- Eigenvalue Decomposition: The eigenvalues ( \lambdai ) and eigenvectors ( yi ) of ( \tilde{S} ) are computed, where the DMD modes are given by ( Uyi ) and the eigenenergies are derived from ( \lambdai ).

A significant advancement is Observable Dynamic Mode Decomposition (ODMD), which formalizes DMD as a stable variational method on the function space of observables available from a quantum many-body system [11]. This approach provides strong theoretical guarantees of rapid convergence even in the presence of substantial perturbative noise, making it particularly suitable for near-term quantum hardware.

Classical Shadows and Fermionic Observables

Classical Shadows constitute a randomized measurement protocol that constructs a classical approximation of a quantum state from which numerous observables can be simultaneously estimated [5]. The technique involves repeatedly preparing the quantum state, applying a random unitary from a carefully selected ensemble, performing computational basis measurements, and then using classical post-processing to reconstruct the state's properties.

For fermionic systems relevant to quantum chemistry, a specialized approach has been developed for efficiently estimating Majorana operators, which form the building blocks of molecular Hamiltonians [5]. The protocol involves:

- Randomization: Applying a set of unitaries that realize products of Majorana fermion operators.

- Fermionic Gaussian Unitaries: Sampling from a constant-size set of suitably chosen fermionic Gaussian unitaries.

- Occupation Number Measurement: Measuring fermionic occupation numbers.

- Post-Processing: Classically processing the results to estimate expectation values.

This scheme can estimate expectation values of all quadratic and quartic Majorana monomials to precision ( \epsilon ) using ( \mathcal{O}(N\log(N)/\epsilon^{2}) ) and ( \mathcal{O}(N^{2}\log(N)/\epsilon^{2}) ) measurement rounds respectively, matching the performance guarantees of fermionic classical shadows while offering potential advantages in circuit depth and gate count [5].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Measurement-Driven Approaches

| Feature | Dynamic Mode Decomposition (ODMD) | Classical Shadows (Fermionic) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | Eigenenergy estimation from time dynamics | Efficient estimation of multiple observables |

| Quantum Data Required | Time-series measurements of observables | Randomized single-qubit measurements |

| Key Innovation | Koopman operator approximation | Classical representation of quantum states |

| Theoretical Guarantees | Rapid convergence with noise resilience | Proven bounds on sample complexity |

| Measurement Rounds | Depends on system dynamics and desired precision | ( \mathcal{O}(N^2 \log N / \epsilon^2) ) for quartic Majoranas [5] |

| Circuit Depth (2D Lattice) | Not explicitly specified | ( \mathcal{O}(N^{1/2}) ) with JW transformation [5] |

| Noise Resilience | Proven robust to perturbative noise [11] | Affected by errors on at most two qubits per estimate [5] |

Application Notes: Protocols for Quantum Chemical Hamiltonians

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item | Function/Description | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Fermionic Gaussian Unitaries | Constant-depth circuits for rotating fermionic modes | Enables joint measurement of Majorana operators in Classical Shadows approach [5] |

| Jordan-Wigner Transformation | Encodes fermionic systems onto qubit processors | Essential for implementing quantum chemistry problems on quantum hardware [5] |

| Classical Post-Processing Pipeline | Algorithms for reconstructing observables from raw data | Critical component for both DMD and Classical Shadows approaches |

| Random Unitary Ensemble | Pre-defined set of unitaries for state randomization | Forms core of Classical Shadows measurement protocol |

| Time-Evolution Circuitry | Quantum circuits for implementing real-time dynamics | Required for ODMD to generate time-series data [11] |

ODMD Protocol for Ground State Energy Estimation

Objective: Estimate the ground state energy of a quantum chemical Hamiltonian with provable noise resilience.

Materials:

- Quantum processor capable of preparing initial states and performing time evolution

- Measurement apparatus for quantum observables

- Classical computing resources for post-processing

Procedure:

- Initial State Preparation: Prepare a reference state ( |\psi_0\rangle ) with non-zero overlap with the true ground state.

- Time Evolution and Sampling: Evolve the state under the system Hamiltonian ( H ) for a sequence of time points ( t1, t2, \dots, t_N ).

- Observable Measurement: At each time point ( ti ), measure a set of observables ( {O1, O2, \dots, Ok} ) to form snapshot vectors ( v_i ).

- Data Matrix Construction: Construct data matrices ( V1^{N-1} = [v1, v2, \dots, v{N-1}] ) and ( V2^{N} = [v2, v3, \dots, vN] ).

- ODMD Execution: a. Compute the SVD: ( V1^{N-1} = U \Sigma W^T ), truncating small singular values for noise reduction. b. Form the matrix ( \tilde{S} = U^T V2^{N} W \Sigma^{-1} ). c. Compute the eigenvalues ( \lambdai ) of ( \tilde{S} ). d. Extract eigenenergies via ( Ei = \frac{\text{Im}(\log \lambda_i)}{\Delta t} ), where ( \Delta t ) is the time step.

- Ground State Identification: Identify the ground state energy as the smallest real-valued ( E_i ) that persists across different temporal sampling rates.

Validation: The protocol's convergence should be verified using benchmark systems with known solutions. The noise resilience can be tested by intentionally introducing depolarizing noise or readout error and confirming stable energy estimation [11].

Joint Measurement Protocol for Fermionic Hamiltonians

Objective: Efficiently estimate all quadratic and quartic terms in a molecular Hamiltonian with reduced circuit depth.

Materials:

- Quantum processor with fermion-to-qubit mapping capability

- Randomized unitary compilation tools

- Classical computation resources for correlation function estimation

Procedure:

- Hamiltonian Decomposition: Express the molecular Hamiltonian in terms of Majorana operators ( \gamma_A ) of degree 2 and 4.

- Measurement Strategy Selection: a. For a given measurement round, sample a unitary from the set realizing products of Majorana operators. b. Apply a randomly selected fermionic Gaussian unitary from a pre-computed set (2 for quadratic terms, 9 for quartic terms).

- Quantum Execution: a. Prepare the quantum state of interest ( \rho ). b. Apply the selected random unitaries. c. Measure fermionic occupation numbers (equivalent to Pauli Z measurements under Jordan-Wigner).

- Classical Post-Processing: a. For each measurement outcome, reconstruct the expectation values of noisy versions of the Majorana monomials. b. Combine results across rounds to estimate the true expectation values ( \langle \gamma_A \rangle ).

- Energy Computation: Reconstruct the total energy by combining the estimated Majorana expectation values with their respective Hamiltonian coefficients.

Implementation Notes: On a rectangular lattice of qubits with Jordan-Wigner transformation, this protocol can be implemented with circuit depth ( \mathcal{O}(N^{1/2}) ) and ( \mathcal{O}(N^{3/2}) ) two-qubit gates, offering improvement over standard fermionic classical shadows that require depth ( \mathcal{O}(N) ) [5].

Figure 1: Fermionic Joint Measurement Protocol Workflow

Comparative Analysis and Implementation Guidelines

Performance Benchmarks and Resource Estimation

Recent numerical benchmarks on exemplary molecular Hamiltonians demonstrate that the joint measurement strategy for fermionic observables achieves sample complexities comparable to fermionic classical shadows while offering advantages in experimental feasibility [5]. Similarly, ODMD has shown accelerated convergence and favorable resource reduction over state-of-the-art algorithms like variational quantum eigensolvers in tests on spin and molecular systems [11].

Table 3: Implementation Considerations for Different Research Scenarios

| Research Scenario | Recommended Approach | Rationale | Key Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) Devices | Observable Dynamic Mode Decomposition | Proven resilience to perturbative noise; avoids barren plateaus [11] | Time steps: 10-100; Snapshot frequency: adapted to coherence times |

| Large-Scale Fermionic Systems | Fermionic Joint Measurement Protocol | Favorable scaling ( \mathcal{O}(N^2 \log N) ) for quartic terms; reduced circuit depth [5] | Measurement rounds: ~(N^2/\epsilon^2); Unitary set size: 2 (quadratic), 9 (quartic) |

| Early Fault-Tolerant Quantum Computation | Hybrid DMD/Shadows Approach | Combines dynamical information with efficient observable estimation | Customized based on specific hardware capabilities and error rates |

| Quantum Drug Discovery Pipelines | Protocol Selection Based on Molecular Size | Small molecules: ODMD; Large complexes: Fermionic Shadows | Balance between accuracy requirements and computational resources |

Integrated Workflow for Quantum Chemical Applications

For industrial applications in drug development, we propose an integrated workflow that leverages the complementary strengths of both approaches:

Figure 2: Integrated Quantum Chemistry Workflow

This integrated approach enables drug development researchers to select the optimal measurement strategy based on their specific molecular system and available quantum resources. The cross-validation step ensures reliability of results, which is critical for making informed decisions in the drug discovery pipeline.

Measurement-driven approaches represent a paradigm shift in how we extract information from quantum systems for chemical applications. Both Dynamic Mode Decomposition and Classical Shadows offer complementary advantages for tackling the challenging problem of quantum chemical Hamiltonian estimation. ODMD provides a noise-resilient path to eigenenergy estimation with proven convergence guarantees, while fermionic joint measurement strategies enable efficient estimation of numerous observables with favorable scaling properties. For researchers in drug development, these protocols offer a practical pathway to leverage current and near-term quantum hardware for molecular simulation problems, potentially accelerating the discovery of novel therapeutic compounds. As quantum hardware continues to mature, the integration of these measurement-driven approaches into standardized quantum chemistry toolkits will be essential for realizing the full potential of quantum computing in pharmaceutical research.

Implementing Efficient Protocols on Near-Term Quantum Hardware

Accurately measuring the properties of complex quantum systems, such as molecular Hamiltonians in quantum chemistry, is a fundamental challenge on near-term quantum hardware. These devices are characterized by significant noise, limited qubit connectivity, and constrained gate depths, which demand the development of resilient and resource-efficient measurement protocols. This application note details practical strategies for estimating the energy of quantum chemical Hamiltonians, focusing on techniques that mitigate hardware limitations while maintaining high precision. Framed within the broader thesis of advancing resilient measurement protocols, this document provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with structured experimental methodologies, performance data, and actionable implementation workflows.

Foundational Measurement Strategies

The high sample counts ("shot overhead") and susceptibility to readout errors on near-term devices make simplistic measurement approaches prohibitive. Advanced strategies that group measurements or extract more information per state preparation are essential.

Informationally Complete (IC) Measurements: IC measurements allow for the estimation of multiple observables from the same set of measurement data. This is particularly beneficial for measurement-intensive algorithms like ADAPT-VQE and error mitigation methods. A key advantage is the seamless interface they provide for performing Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT), which can characterize and correct readout errors, thereby reducing estimation bias [16].

Classical Shadows and Joint Measurements: The classical shadows technique uses randomized measurements to build a classical approximation of a quantum state, enabling the estimation of many non-commuting observables without repeated state re-preparation [5]. For fermionic systems, a related approach is a joint measurement scheme for Majorana operators. This method can estimate all quadratic and quartic terms in a Hamiltonian using a number of measurement rounds that scales as ( \mathcal{O}(N^2 \log(N)/\epsilon^2) ) for a given precision ( \epsilon ) in an N-mode system, matching the performance of fermionic classical shadows but with potential advantages in circuit depth [5].

Locally Biased Random Measurements: This technique reduces shot overhead by prioritizing measurement settings that have a larger impact on the final energy estimation. By intelligently biasing the selection of measurements, this strategy maintains the informationally complete nature of the protocol while requiring fewer total shots to achieve a desired precision [16].

Table 1: Comparison of Key Measurement Strategies

| Strategy | Key Principle | Advantages | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Informationally Complete (IC) Measurements | Measure a complete set of observables to reconstruct state properties. | Enables estimation of multiple observables from one data set; facilitates error mitigation via QDT [16]. | Requires careful calibration of measurement apparatus. |

| Classical Shadows / Joint Measurements | Use randomized measurements to create a classical snapshot of the quantum state [5]. | Efficient for many observables; performance guarantees for fermionic systems [5]. | Randomization over a large set of unitaries may be complex. |

| Locally Biased Random Measurements | Prioritize measurement settings that maximize information gain for a specific task (e.g., energy estimation) [16]. | Reduces shot overhead while preserving unbiased estimation [16]. | Requires prior knowledge about the Hamiltonian. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Joint Measurement of Fermionic Observables

This protocol is designed for the efficient estimation of expectation values for quadratic and quartic Majorana monomials, which constitute typical quantum chemistry Hamiltonians [5].

1. Objective: To estimate the expectation values of all Majorana pairs and quadruples in an N-mode fermionic system to a precision ( \epsilon ).

2. Materials and Setup:

- A quantum processor capable of preparing the target fermionic state (e.g., via the Jordan-Wigner transformation).

- Control hardware to execute fermionic Gaussian unitaries and measure occupation numbers.

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Unitary Randomization. For each measurement round, sample a unitary ( U ) from a predefined set. This set consists of:

- A subset of unitaries that realize products of Majorana operators.

- A second subset of specially chosen fermionic Gaussian unitaries. For quartic monomials, a set of nine such unitaries is sufficient [5].

- Step 2: Occupation Number Measurement. Apply the selected unitary ( U ) to the prepared quantum state.

- Step 3: Classical Post-processing. Process the measured occupation numbers (bitstrings) to compute the estimates for the noisy versions of the targeted Majorana observables. The final estimate is obtained by averaging over many measurement rounds [5].

4. Performance and Resource Estimation:

- Sample Complexity: ( \mathcal{O}(N \log(N)/\epsilon^2) ) rounds for quadratic terms and ( \mathcal{O}(N^2 \log(N)/\epsilon^2) ) for quartic terms [5].

- Circuit Depth: On a 2D rectangular qubit lattice, the circuit depth is ( \mathcal{O}(N^{1/2}) ) with ( \mathcal{O}(N^{3/2}) ) two-qubit gates, offering an improvement over some classical shadow methods [5].

Protocol 2: High-Precision Measurement with QDT and Blending

This protocol integrates several practical techniques to combat readout errors and temporal noise drift on real hardware, as demonstrated for molecular energy estimation [16].

1. Objective: To achieve high-precision (e.g., chemical precision at ( 1.6 \times 10^{-3} ) Hartree) estimation of a molecular energy, mitigating readout errors and time-dependent noise.

2. Materials and Setup:

- A parameterized ansatz state (e.g., Hartree-Fock state) prepared on a quantum device.

- Access to the device's control system to implement blended scheduling of circuits.

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Circuit Execution with Blending. Instead of running all circuits for a single Hamiltonian consecutively, interleave (blend) the execution of circuits for different Hamiltonians (e.g., for ground and excited states) and QDT circuits. This ensures temporal noise fluctuations affect all computations evenly [16].

- Step 2: Parallel Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT). In parallel with the main computation, execute a set of circuits that characterize the readout error matrix of the device.

- Step 3: Biased Measurement Selection. Use a locally biased measurement strategy to select settings that minimize the shot overhead for the target Hamiltonian [16].

- Step 4: Error-Mitigated Estimation. Use the measurement data from the main circuits, along with the characterized error matrix from QDT, to construct an unbiased estimator of the energy via post-processing [16].

4. Performance: This combined approach has been shown to reduce measurement errors from the 1-5% range to about 0.16% for an 8-qubit molecular Hamiltonian (BODIPY) on an IBM quantum processor [16].

Performance Analysis and Benchmarking

Quantitative Performance Metrics

The presented protocols have been benchmarked on representative problems, showing their competitiveness for near-term applications.

Table 2: Benchmarking Results for Measurement Protocols

| Protocol / Strategy | System Benchmarked | Key Performance Result | Hardware Platform |

|---|---|---|---|

| Joint Fermionic Measurement [5] | Exemplary molecular Hamiltonians | Sample complexity matches fermionic classical shadows; Reduced circuit depth on 2D lattices. | N/A (Theoretical analysis) |

| IC Measurements with QDT & Blending [16] | BODIPY-4 molecule (8-qubit H) | Error reduction from 1-5% to 0.16% on a noisy device. | IBM Eagle r3 |

| Dynamic Circuits for Shadows [25] | 28- and 40-qubit hydrogen chain models | Enabled classical shadow with 10 million random circuits; 14,000x speedup in execution time. | IBM superconducting device |

| FAST-VQE Algorithm [26] | Butyronitrile dissociation (up to 20 qubits) | Computed full potential energy surface using realistic basis sets on 16- and 20-qubit processors. | IQM Sirius & Garnet |

Resource Overhead Comparison

A critical consideration for near-term hardware is the resource footprint of a protocol.

- Shot Overhead: Locally biased measurements and informationally complete approaches can significantly reduce the number of shots required to achieve chemical precision compared to naive measurement grouping [16].

- Circuit Overhead: Using dynamic circuits to generate probability distributions on the quantum hardware itself can drastically reduce the execution time of randomized algorithms. One demonstration showed a 14,000-fold acceleration for implementing classical shadows [25].

- Calibration Overhead: Protocols requiring specialized gate sets or frequent recalibration may not be practical. The use of hardware-native gates and robust techniques like blended scheduling helps manage this overhead [16] [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit

This section details the essential components for implementing the described resilient measurement protocols.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Quantum Measurement

| Item / Technique | Function / Role in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| Fermionic Gaussian Unitaries | A core component in the joint measurement protocol [5]. They rotate the fermionic mode basis, allowing a single measurement setting (occupation numbers) to provide information about many non-commuting Majorana observables. |

| Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT) | A calibration technique used to characterize the readout errors of a quantum device [16]. The resulting error model is used in post-processing to mitigate noise and reduce bias in the final estimate. |

| Dynamic Circuits | Quantum circuits that incorporate intermediate measurements and real-time feedback [25]. They enable massive efficiency gains for randomized algorithms by generating probability distributions on the quantum hardware, avoiding the latency of classical communication. |

| Blended Scheduling | An execution strategy that interleaves circuits from different computational tasks (e.g., for different molecular states) [16]. This mitigates the impact of slow, time-dependent noise drifts in the hardware by ensuring all computations experience an average of the noise over time. |

| Locally Biased Estimator | A classical post-processing algorithm that assigns a non-uniform probability distribution to the selection of measurement settings [16]. This biases the sampling towards settings that provide more information for a specific Hamiltonian, thus reducing the number of shots (sample complexity) required. |

| Alvimopan | Alvimopan, CAS:156053-89-3, MF:C25H32N2O4, MW:424.5 g/mol |

| Asperlicin D | Asperlicin D, CAS:93413-07-1, MF:C25H18N4O2, MW:406.4 g/mol |

Implementation Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the logical flow and key components of the primary experimental protocols.

Workflow for Joint Fermionic Measurement

Workflow for High-Precision Measurement with QDT

The efficient implementation of measurement protocols on near-term quantum hardware is a critical enabler for practical quantum chemistry and drug discovery applications. The strategies outlined in this document—including joint measurements of fermionic observables, dynamic circuit compilation, and a suite of error mitigation techniques like QDT and blended scheduling—provide a roadmap for achieving the high-precision energy estimation required for impactful molecular simulations. By adopting these resilient protocols, researchers can significantly mitigate the limitations of current noisy hardware and accelerate the path toward quantum-accelerated scientific discovery.

The accurate simulation of molecular systems is a cornerstone of advancements in drug discovery and materials science. For near-term quantum hardware, significant challenges persist due to limitations in qubit counts, circuit fidelity, and resilience against noise. This document details application notes and experimental protocols for applying resilient measurement strategies to the simulation of small molecules—H₂, LiH, and H₄—framed within a broader research thesis on noise-resilient techniques for quantum chemical Hamiltonians. The following sections provide quantitative performance comparisons and step-by-step methodologies for researchers aiming to reproduce these results.

Simulations of small molecules demonstrate the efficacy of advanced quantum algorithms. The tables below summarize key performance metrics for the K-ADAPT-VQE algorithm and the Joint Measurement strategy, providing a benchmark for expected performance on molecular systems of interest [28] [5].

Table 1: Performance Metrics of K-ADAPT-VQE Algorithm on Small Molecules [28]

| Molecule | Key Performance Metric | Reported Value | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hâ‚‚ | Achieves chemical accuracy | Within ~1 kcal/mol | Substantial reduction in iterations & function evaluations. |

| LiH | Achieves chemical accuracy | Within ~1 kcal/mol | Substantial reduction in iterations & function evaluations. |

| Hâ‚„O | Achieves chemical accuracy | Within ~1 kcal/mol | Demonstrates performance on larger systems. |

| C₂H₆ | Achieves chemical accuracy | Within ~1 kcal/mol | Demonstrates performance on larger systems. |

Table 2: Resource Scaling of Fermionic Observable Estimation (Joint Measurement) [5]

| Observable Type | Majorana Monomial Degree | Measurement Rounds for Precision ϵ | Key Hardware Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quadratic | 2 | ( \mathcal{O}(N \log(N) / \epsilon^{2}) ) | Circuit depth ( \mathcal{O}(N^{1/2}) ) on 2D lattice |

| Quaternary | 4 | ( \mathcal{O}(N^{2} \log(N) / \epsilon^{2}) ) | Circuit depth ( \mathcal{O}(N^{1/2}) ) on 2D lattice |

Experimental Protocols