Solving the Electronic Structure Problem: Quantum Chemistry Fundamentals for Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the electronic structure problem in quantum chemistry, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Solving the Electronic Structure Problem: Quantum Chemistry Fundamentals for Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the electronic structure problem in quantum chemistry, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational theory behind calculating molecular electronic properties, a detailed analysis of prevalent computational methods from Density Functional Theory to emerging geminal-based approaches, and critical strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing calculations, including geometry minimization and dispersion correction. Furthermore, it establishes a rigorous framework for the validation and benchmarking of computational results against both high-level theoretical models and experimental data, highlighting the direct implications for accurate biomolecular simulation and rational drug design.

The Quantum Chemical Foundation: From Schrödinger's Equation to Chemical Bonds

The electronic structure problem represents one of the most central challenges in physical sciences, forming the critical connection between quantum mechanics and the predictive computational modeling of molecular systems. At its heart lies the many-body Schrödinger equation, a fundamental framework for describing the behavior of electrons in molecular systems based on quantum mechanics [1]. This equation largely forms the basis for quantum-chemistry-based energy calculations and has become the core concept of modern electronic structure theory [1]. The electronic structure of all materials, in principle, can be determined by solving the Schrödinger equation to obtain the wave function, which contains all information about the quantum-mechanical system [2] [3]. However, the complexity of this equation increases exponentially with the growing number of interacting particles, rendering its exact solution intractable for most practical cases and creating the essential challenge that defines the electronic structure problem in quantum chemistry [1].

In the context of quantum chemistry fundamentals research, this problem amounts to solving the static Schrödinger equation for molecular systems, which can be formulated on a discrete molecular basis set [4]. The Born-Oppenheimer Hamiltonian provides the standard mathematical formulation:

$$ \hat{H}|\Psi\rangle = E|\Psi\rangle $$

where $|\Psi\rangle$ represents the wave function of the system, $E$ is the energy eigenvalue, and $\hat{H}$ is the Hamiltonian operator that encapsulates the total energy of the electronic system [4]. For molecular systems in second quantization, this Hamiltonian takes the form:

$$ \hat{H} = \sum{\substack{pr\ \sigma}}h{pr}\hat{a}^{\dagger}{p\sigma}\hat{a}^{\phantom{\dagger}}{r\sigma} + \sum{\substack{prqs\ \sigma\tau}}\frac{(pr|qs)}{2}\hat{a}^{\dagger}{p\sigma}\hat{a}^{\dagger}{q\tau}\hat{a}^{\phantom{\dagger}}{s\tau}\hat{a}^{\phantom{\dagger}}_{r\sigma} $$

Here, we have defined the fermionic creation/annihilation operators $\hat{a}^{\dagger}{p\sigma}$/$\hat{a}^{\phantom{\dagger}}{p\sigma}$ associated with the $p$-th basis set element and spin-$\sigma$ polarization, while $h_{pr}$ and $(pr|qs)$ are the one- and two-body electronic integrals [4]. The exponential complexity arises from the anti-symmetry requirements of the wave function for fermionic systems and the entangled nature of electron correlations, making the electronic structure problem both theoretically nuanced and computationally demanding.

The Mathematical Core: Understanding the Many-Body Challenge

The Exponential Scaling Problem

The central challenge of the many-body Schrödinger equation lies in its exponential scaling with system size. For an N-electron system, the many-body wave function Ψ is a complex, simultaneous function of 3N spatial coordinates [5]. This complexity derives from the entanglement of electronic motion through quantum statistical correlations (due to the Pauli exclusion principle), and spatial correlations mediated by Ψ [5]. In practical terms, for a molecular system with an active space of 50 electrons in 36 orbitals, the dimension of the corresponding Hilbert space becomes $\binom{36}{25}*\binom{36}{25} = 3.61 \cdot 10^{17}$ [4]. This scale is several orders of magnitude beyond the current capability of exact diagonalization, which is limited to approximately $1.0 \cdot 10^{12}$ [4].

The mathematical formulation of quantum mechanics defines the state of a quantum mechanical system to be a vector $|\psi\rangle$ in a Hilbert space $\mathcal{H}$, where physical quantities of interest—position, momentum, energy, spin—are represented by observables acting on this space as self-adjoint operators [3]. When an observable is measured, the result will be one of its eigenvalues with probability given by the Born rule, further complicating the computational task of predicting molecular properties [3].

Manifestations in Complex Molecular Systems

The practical implications of this exponential scaling become particularly evident in challenging chemical systems such as iron-sulfur clusters, which represent a universal biological motif found in various metalloproteins [4]. These clusters, including ferredoxins, hydrogenases, and nitrogenase, participate in remarkable chemical reactions at ambient temperature and pressure [4]. Their electronic structure—featuring multiple low-energy wavefunctions with diverse magnetic and electronic character—poses a formidable challenge for classical numerical methods.

Practical simulations based on mean-field approximations that treat only classical-like quantum states without entanglement are fundamentally inadequate for such systems because the iron 3d shells are partially filled and near-degenerate on the Coulomb interaction scale, leading to strong electronic correlation in low-energy wavefunctions [4]. This reality invalidates any independent-particle picture and the related concept of a mean-field electronic configuration, necessitating more sophisticated approaches that can handle the strongly correlated nature of these systems.

Computational Methodologies: Approximation Strategies and Their Foundations

Traditional Approximation Methods

To bridge the gap between theoretical exactness and computational feasibility, various approximation strategies have been developed, which largely form the basis of modern quantum chemistry [1]. These methods can be systematically categorized based on their theoretical foundations and approximation strategies:

Table 1: Traditional Electronic Structure Approximation Methods

| Method Category | Key Methods | Theoretical Foundation | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean-Field Theories | Hartree-Fock (HF) | Self-consistent field approximation | Computationally efficient; foundational for other methods | Neglects electron correlation |

| Post-Hartree-Fock Methods | Configuration Interaction (CI), Perturbation Theory (MPn), Coupled Cluster (CC) | Systematic inclusion of electron excitations | Systematic improvability; high accuracy for weak correlation | High computational cost; steep scaling |

| Density-Based Methods | Density Functional Theory (DFT) | Hohenberg-Kohn theorems mapping to electron density | Favorable scaling; good accuracy/cost balance | Unknown exact functional; challenges for strong correlation |

| Stochastic Methods | Quantum Monte Carlo (QMC) | Statistical sampling of wave function | Potentially exact; favorable scaling for large systems | Fermionic sign problem; computational expense |

| Tensor Network Methods | Density Matrix Renormalization Group (DMRG) | Matrix product states for 1D systems | High accuracy for strong correlation | Efficiency depends on entanglement structure |

The breakdown of the mean-field approximation in strongly correlated systems like iron-sulfur clusters implies that conventional methods for classical computers—restricted Hartree-Fock (RHF), configuration interaction singles and doubles (CISD), and coupled cluster singles and doubles (CCSD)—often provide inaccurate results [4]. For the [4Fe-4S] cluster, for instance, RHF yields $E{\mathrm{RHF}} = -326.547~E{\mathrm{h}}$ while CISD gives $E{\mathrm{CISD}} = -326.742~E{\mathrm{h}}$ [4]. The state of the art for classical electronic structure computations in such challenging systems is the density matrix renormalization group (DMRG), which has yielded ground-state energy estimates of $E{\mathrm{DMRG,[2Fe-2S]}} = -5049.217~E{\mathrm{h}}$ and $E{\mathrm{DMRG,[4Fe-4S]}} = -327.239~E{\mathrm{h}}$ [4].

Emerging Computational Strategies

Recent years have witnessed the development of several innovative approaches that push beyond traditional methodologies:

Neural Network Quantum States (NNQS): The seminal work by Carleo and Troyer in 2017 introduced a groundbreaking approach for tackling many-spin systems within the exponentially large Hilbert space by parameterizing the quantum wave function with a neural network and optimizing its parameters stochastically using the variational Monte Carlo (VMC) algorithm [2]. This framework has evolved along two distinct paths: first quantization, which works directly in continuous space, and second quantization, which operates in a discrete basis [2].

Transformer-Based Quantum States: Recent work has combined Transformer architectures with efficient autoregressive sampling to solve the many-electron Schrödinger equation [2]. The QiankunNet framework features a Transformer-based wave function ansatz that captures complex quantum correlations through attention mechanisms, effectively learning the structure of many-body states [2]. The quantum state sampling employs layer-wise Monte Carlo tree search (MCTS) that naturally enforces electron number conservation while exploring orbital configurations [2].

Quantum-Classical Hybrid Approaches: Building on sample-based quantum diagonalization methods, recent efforts have demonstrated reliable electronic structure simulations with quantum data for up to 85 qubits [4]. These approaches use quantum processors to prepare wavefunction ansatzes that approximate the support of the exact ground state, with subsequent classical processing to project and diagonalize the Hamiltonian on the sampled configurations [4].

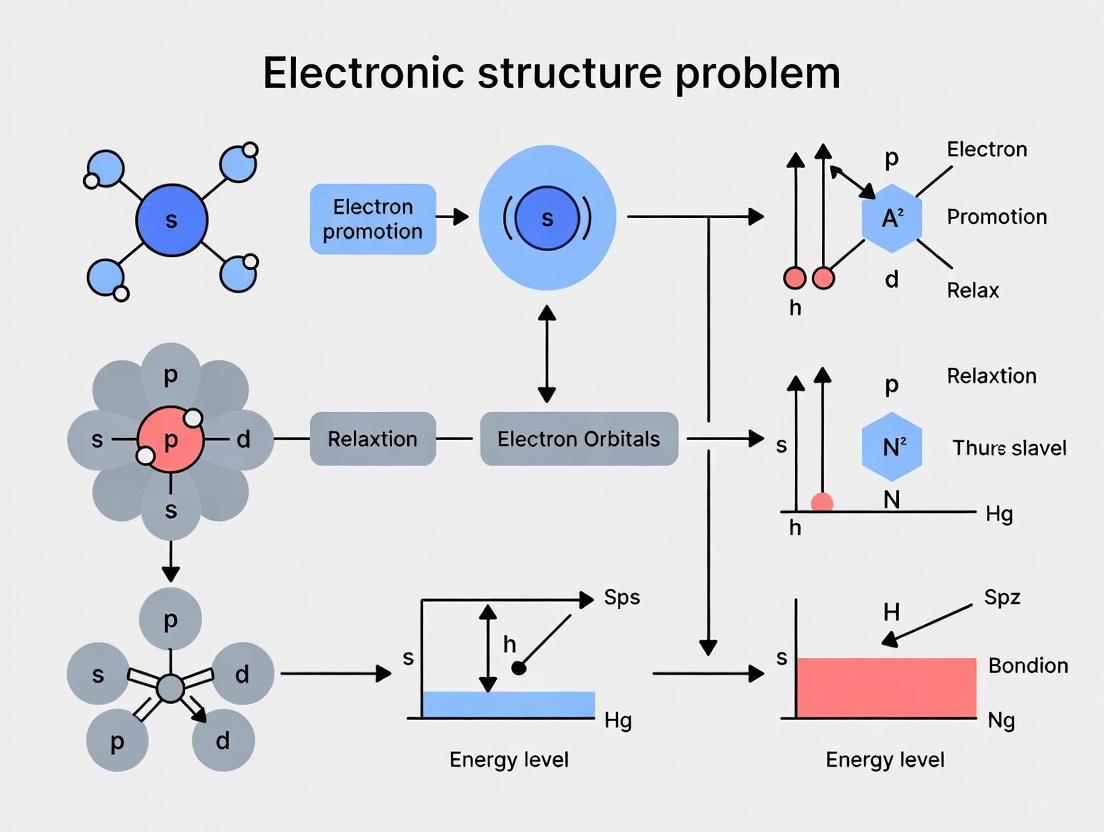

Diagram 1: Computational methodology relationships in electronic structure theory, showing the evolution from traditional to emerging approaches.

Quantitative Benchmarking: Performance Comparison of Modern Methods

Accuracy Metrics and Performance Indicators

The development of approximation methods necessitates rigorous benchmarking against established standards and exact solutions where available. Full configuration interaction (FCI) provides a comprehensive approach to obtain the exact wavefunction within a given basis set, but the exponential growth of the Hilbert space limits the size of feasible FCI simulations [2]. Chemical accuracy, typically defined as an error of 1 kcal/mol (approximately 0.0016 Hartree) in energy differences, serves as the gold standard for methodological validation.

Systematic benchmarks across diverse molecular systems provide critical insights into the relative performance of various approaches. For molecular systems up to 30 spin orbitals, transformer-based neural network approaches like QiankunNet have achieved correlation energies reaching 99.9% of the FCI benchmark, setting a new standard for neural network quantum states [2]. Notably, these methods capture the correct qualitative behavior in regions where standard CCSD and CCSD(T) methods show limitations, particularly at dissociation distances where multi-reference character becomes significant [2].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Selected Electronic Structure Methods for Challenging Molecular Systems

| Method | Theoretical Scaling | [4Fe-4S] Energy (E_h) | N2 Dissociation | CAS(46e,26o) Feasibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RHF | N^3–N^4 | -326.547 | Qualitative Incorrect | Yes |

| CISD | N^6 | -326.742 | Limited Accuracy | Marginal |

| CCSD(T) | N^7 | - | Limited Accuracy | No |

| DMRG | Variable | -327.239 | Accurate | Yes (with approximations) |

| QiankunNet | Polynomial | - | Accurate | Yes (demonstrated) |

| Quantum-Classical (SQD) | - | -326.635 | - | Yes (72 qubits) |

When comparing different NNQS approaches, the Transformer-based neural network adopted in QiankunNet demonstrates heightened accuracy compared to other second-quantized NNQS approaches [2]. For example, while second quantized approaches such as the MADE method cannot achieve chemical accuracy for the Nâ‚‚ system, QiankunNet achieves an accuracy two orders of magnitude higher [2].

Scalability and Resource Requirements

The computational resource requirements for electronic structure calculations vary dramatically across methods, creating practical constraints on their application to realistic chemical systems:

Memory and Storage: Traditional wave function methods exhibit exponential memory requirements with system size, while density-based methods and selected neural network approaches offer more favorable polynomial scaling [2].

Processing Power: Quantum-chemical calculations typically require high-performance computing resources, with computational costs scaling as the fourth power of the number of spin orbitals for energy evaluation steps [2].

Quantum Resources: For quantum computing approaches, active spaces of electrons in 36 spatial orbitals require 72 qubits using the standard Jordan-Wigner map for fermion-to-qubit degrees of freedom [4]. Current quantum-centric supercomputing architectures have been deployed to perform large-scale computations of electronic structure involving quantum and classical high-performance computing, with demonstrations utilizing up to 152,064 classical nodes coordinated with quantum processors [4].

Advanced Technical Implementations: Methodological Deep Dive

Transformer-Based Wavefunction Ansatz

The QiankunNet framework represents a significant advancement in neural network quantum states by combining the expressivity of Transformer architectures with efficient autoregressive sampling [2]. At the heart of this approach lies a Transformer-based wave function ansatz that captures complex quantum correlations through its attention mechanism, effectively learning the structure of many-body states while maintaining parameter efficiency independent of system size [2].

The framework incorporates several key innovations:

Autoregressive Sampling with MCTS: The quantum state sampling employs a Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS)-based autoregressive approach that introduces a hybrid breadth-first/depth-first search (BFS/DFS) strategy [2]. This provides sophisticated control over the sampling process through a tunable parameter that allows adjustment of the balance between exploration breadth and depth. The strategy significantly reduces memory usage while enabling computation of larger and deeper quantum systems by managing the exponential growth of the sampling tree more efficiently [2].

Physics-Informed Initialization: The framework incorporates physics-informed initialization using truncated configuration interaction solutions, providing principled starting points for variational optimization and significantly accelerating convergence [2].

Parallel Implementation: The method implements explicit multi-process parallelization for distributed sampling, enabling partitioning of unique sample generation across multiple processes and significantly improving scalability for large quantum systems [2]. Key-value (KV) caching specifically designed for Transformer-based architectures achieves substantial speedups by avoiding redundant computations of attention keys and values during the autoregressive generation process [2].

Quantum-Classical Hybrid Workflows

The integration of quantum and classical computing resources represents another frontier in electronic structure computation. Closed-loop workflows between quantum processors and classical supercomputers have been designed to approximate the electronic structure of chemistry models beyond the reach of exact diagonalization, with accuracy comparable to some all-classical approximation methods [4].

In these workflows, a set of quantum measurements from a quantum circuit first undergoes a configuration recovery step, and then is processed by a classical computer to project and diagonalize the Hamiltonian on the sampled set of configurations [4]. The size and constituents of this configuration set determine the accuracy of the approximate target eigenstate [4]. This approach has been successfully applied to investigate multireference ground-state wavefunctions in iron-sulfur clusters with active spaces of 50 electrons in 36 orbitals and 54 electrons in 36 orbitals [4].

Diagram 2: Quantum-classical hybrid workflow for electronic structure calculation, showing the integration between quantum and classical resources.

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

The implementation of advanced electronic structure methods requires both theoretical sophistication and specialized computational tools. The following table summarizes key "research reagents" – essential software, algorithms, and mathematical tools – that enable cutting-edge research in this field.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Advanced Electronic Structure Research

| Category | Tool/Algorithm | Specific Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mathematical Frameworks | Grassmannians from differential geometry | Acceleration of quantum chemistry calculations | Small to large molecule computations [6] |

| Fragmentations from set theory | System decomposition for computational efficiency | Large, condensed phase systems [6] | |

| Neural Network Architectures | Transformer-based wave function ansatz | Capturing complex quantum correlations via attention | Molecular systems to 30 spin orbitals [2] |

| Autoregressive sampling | Direct generation of uncorrelated electron configurations | Avoiding MCMC sampling limitations [2] | |

| Quantum Computing Tools | Local Unitary Cluster Jastrow (LUCJ) circuit | Wavefunction ansatz preparation on quantum hardware | Iron-sulfur cluster simulations [4] |

| Jordan-Wigner transformation | Fermion-to-qubit mapping for quantum computation | 72-qubit simulations [4] | |

| Classical Computational Tools | Q-Chem quantum chemistry software | Platform for method development and application | Noncovalent interaction studies [6] |

| Density matrix renormalization group (DMRG) | Handling strongly correlated electron systems | Iron-sulfur cluster benchmark calculations [4] |

Applications to Challenging Chemical Systems: Case Studies

The Fenton Reaction Mechanism

The capabilities of modern electronic structure methods are particularly evident in their application to chemically significant problems such as the Fenton reaction mechanism, a fundamental process in biological oxidative stress [2]. QiankunNet has successfully handled a large CAS(46e,26o) active space for this system, enabling accurate description of the complex electronic structure evolution during Fe(II) to Fe(III) oxidation [2]. This achievement demonstrates the potential of neural network quantum states to address chemically relevant systems with substantial complexity and strong correlation effects.

Iron-Sulfur Clusters

As noted previously, iron-sulfur clusters present exceptional challenges for electronic structure methods due to their complex electronic configurations with diverse magnetic and electronic character [4]. The accurate computation of these systems must involve entangled superpositions of multiple electronic configurations [4]. While the number of such configurations scales combinatorially with the number of iron and sulfur atoms in the cluster, methods that impose structure on these entangled superpositions – such as DMRG and quantum-classical hybrid approaches – have enabled elevation of quantum simulations from the mean-field level to the level of correlated many-body quantum mechanics required to describe the cluster's low-energy properties [4].

Noncovalent Interactions in Drug Development

Another significant application area lies in the investigation of noncovalent interactions in large and/or complex systems, which is a challenging problem for electronic structure theory [6]. Tuning noncovalent interactions in drug binding and organic molecular materials is a key step in controlling the efficacy of drug molecules and function of molecular materials [6]. The development of fast and accurate approaches for gaining a fundamental understanding of the factors governing drug binding and molecular materials packing provides a basis for the development of new drug molecules and functionalized molecular materials [6].

Future Directions and Research Frontiers

The field of electronic structure theory continues to evolve rapidly, with several promising research frontiers emerging:

Machine Learning Acceleration: Research is actively exploring the acceleration of quantum chemistry calculations using machine learning techniques [6]. Adaptation of methodology to the rapid evolution of machine-learning techniques offers a unique opportunity to generate new noncovalent molecular electronics and drug molecules through large-scale computational screening and design [6].

Quantum Computing Integration: As quantum computing hardware continues to advance, research is focused on developing noise-resilient algorithms for NISQ (noisy intermediate-scale quantum) architectures [5]. Investigations are underway to determine whether the DFT formulation of the electronic structure problem can be more resilient to noise on current-generation NISQ computers compared to traditional wavefunction-based electronic structure methods [5].

Methodological Hybridization: Future progress is likely to involve increased hybridization of methodologies, combining the strengths of different approaches to overcome their individual limitations. For instance, the combination of different strategies to functionalize molecules offers seemingly infinite possibilities for methodological innovation [6].

The electronic structure problem, centered on the challenge of solving the many-body Schrödinger equation, remains a vibrant and critically important area of research in quantum chemistry. While significant challenges persist, the continued development of sophisticated approximation strategies – from traditional quantum chemical methods to emerging neural network and quantum computing approaches – provides a robust foundation for increasingly reliable predictions of molecular structure, energetics, and dynamics with reduced computational costs [1]. These advances promise to expand the frontiers of computational chemistry, enabling accurate treatment of previously intractable systems and contributing to advancements in drug discovery, materials design, and fundamental chemical understanding.

The Born-Oppenheimer (BO) approximation represents a foundational concept in quantum chemistry that enables the practical solution of the molecular Schrödinger equation by separating the motions of electrons and atomic nuclei. This approximation, predicated on the significant mass disparity between electrons and nuclei, allows for the parameterization of electronic wavefunctions based on nuclear coordinates and forms the bedrock upon which modern computational chemistry is built. This technical guide examines the rigorous mathematical formulation of the approximation, its physical justification rooted in mass ratio considerations, practical implementation methodologies for electronic structure calculations, and identified limitations where the approximation fails, particularly in non-adiabatic processes involving conical intersections. Within the broader context of the electronic structure problem in quantum chemistry fundamentals research, the BO approximation provides the theoretical justification for concepts essential to chemical reasoning, including molecular structure and potential energy surfaces.

The Molecular Schrödinger Equation

In the absence of external fields, the non-relativistic, time-independent molecular Hamiltonian for a system comprising M nuclei and N electrons is given in atomic units by [7]:

$$ \hat{H} = -\sum{A=1}^{M}\frac{1}{2MA}\nabla{\vec{RA}}^2 - \sum{i=1}^{N}\frac{1}{2}\nabla{\vec{ri}}^2 - \sum{A=1}^{M}\sum{i=1}^{N}\frac{ZA}{|\vec{RA}-\vec{ri}|} + \sum{i=1}^{N-1}\sum{j>i}^{N}\frac{1}{|\vec{ri}-\vec{rj}|} + \sum{A=1}^{M-1}\sum{B>A}^{M}\frac{ZA ZB}{|\vec{RA}-\vec{RB}|} $$

The terms represent, in order: nuclear kinetic energy, electronic kinetic energy, electron-nuclear attraction, electron-electron repulsion, and nuclear-nuclear repulsion. This Hamiltonian operates on the total molecular wavefunction, Ψtotal(R, r), which depends on the coordinates of all nuclei (R) and all electrons (r), through the eigenvalue equation ŤΨ = EΨ [7]. The complexity of solving this equation scales dramatically with system size; for example, the benzene molecule (C6H6) requires dealing with a wavefunction depending on 162 coordinates (36 nuclear + 126 electronic) [8].

The Central Challenge of the Electronic Structure Problem

The electronic structure problem in quantum chemistry fundamentally concerns determining the stationary states and corresponding energy eigenvalues of this molecular Hamiltonian. The principal challenges are:

- Dimensionality: The wavefunction depends on 3(M+N) coordinates, creating an exponentially scaling computational problem.

- Coupling: The motions of all particles are intrinsically coupled through potential energy terms, particularly the electron-nuclear attraction.

- Non-separability: The interparticle interactions prevent exact separation of variables.

Without simplification, direct solution of the molecular Schrödinger equation remains computationally intractable for all but the smallest molecular systems. The Born-Oppenheimer approximation provides the most critical simplification enabling practical quantum chemical calculations.

Theoretical Foundation of the Born-Oppenheimer Approximation

Physical Basis: Mass Disparity and Timescale Separation

The BO approximation leverages the significant mass difference between atomic nuclei and electrons. A proton's mass is approximately 1836 times greater than an electron's mass [9]. For equal momentum imparted to both particles, this mass disparity translates directly to velocity differences:

$$ \begin{aligned} \text{Momentum} &= M v{\text{proton}} = m v{\text{electron}} \ &= 1836 \times v{\text{proton}} = 1 \times v{\text{electron}} \ v{\text{electron}}/v{\text{proton}} &= 1836/1 \end{aligned} $$

This quantitative relationship demonstrates that electrons move thousands of times faster than nuclei [9]. Consequently, electrons effectively instantaneously adjust to any changes in nuclear configuration, while nuclei experience electrons as a averaged potential field.

Mathematical Formulation

The BO approximation consists of two consecutive steps:

Step 1: Clamped-nuclei Electronic Schrödinger Equation Nuclear kinetic energy is neglected (Tₙ ≈ 0), and nuclear positions are treated as fixed parameters R rather than dynamic variables. This yields the electronic Schrödinger equation [8]:

$$ \hat{H}{\text{el}}(\mathbf{r}; \mathbf{R})\chik(\mathbf{r}; \mathbf{R}) = E{\text{el},k}(\mathbf{R})\chik(\mathbf{r}; \mathbf{R}) $$

where $$ \hat{H}{\text{el}} = -\sum{i}\frac{1}{2}\nablai^2 - \sum{i,A}\frac{ZA}{r{iA}} + \sum{i>j}\frac{1}{r{ij}} + \sum{B>A}\frac{ZA ZB}{R{AB}} $$

The electronic energy Eâ‚‘â‚—,k(R) depends parametrically on nuclear coordinates and defines the potential energy surface (PES) for the k-th electronic state.

Step 2: Nuclear Schrödinger Equation With the PES established, nuclear motion is described by [8]:

$$ [\hat{T}n + E{\text{el},k}(\mathbf{R})]\phik(\mathbf{R}) = E\phik(\mathbf{R}) $$

This equation treats nuclei as moving on the potential energy surface Eâ‚‘â‚—,k(R) generated by the electrons in a specific quantum state.

Table 1: Components of the Molecular Hamiltonian Under the BO Approximation

| Component | Full Hamiltonian | BO Electronic Hamiltonian | BO Nuclear Hamiltonian |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nuclear Kinetic Energy | Included | Neglected | Included |

| Electronic Kinetic Energy | Included | Included | Not present |

| Electron-Nuclear Potential | Included | Included (nuclei as parameters) | Not present |

| Electron-Electron Potential | Included | Included | Not present |

| Nuclear-Nuclear Potential | Included | Included (constant for fixed R) | Included in Eâ‚‘â‚—(R) |

Wavefunction Factorization and Energy Separation

The BO approximation enables factorization of the total wavefunction:

$$ \Psi{\text{total}} \approx \psi{\text{electronic}} \cdot \psi_{\text{nuclear}} $$

This product ansatz leads to the separation of molecular energy into distinct contributions [8] [7]:

$$ E{\text{total}} = E{\text{electronic}} + E{\text{vibrational}} + E{\text{rotational}} + E_{\text{translational}} $$

This separation is foundational to molecular spectroscopy, where transitions between different types of energy levels correspond to distinct regions of the electromagnetic spectrum.

Computational Implementation and Workflow

The BO approximation enables practical computational chemistry through a well-defined workflow that separates electronic structure calculations from nuclear motion treatment.

Diagram 1: BO Approximation Computational Workflow

Electronic Structure Calculation Methodology

For each nuclear configuration, the electronic Schrödinger equation is solved using quantum chemical methods:

Protocol 3.1.1: Electronic Energy Calculation at Fixed Nuclear Geometry

- Input Nuclear Coordinates: Specify atomic identities and positions R in Cartesian or internal coordinates

- Select Basis Set: Choose appropriate atomic orbital basis functions {Ï•â‚} for expanding molecular orbitals

- Construct Electronic Hamiltonian: Compute one-electron (kinetic energy and electron-nuclear attraction) and two-electron (electron-electron repulsion) integrals

- Solve Electronic Eigenvalue Problem: Using self-consistent field (SCF) methods for mean-field solutions or more advanced configuration interaction/coupled cluster approaches for electron correlation

- Compute Properties: From converged electronic wavefunction, determine electron density, molecular orbitals, and other electronic properties

- Output Electronic Energy: Eâ‚‘â‚—(R) for inclusion in potential energy surface

This procedure is repeated for multiple nuclear configurations to map out the potential energy surface, which serves as the foundation for subsequent nuclear motion calculations.

Nuclear Motion Treatment

With the PES established, nuclear dynamics can be treated through several approaches:

Protocol 3.2.1: Nuclear Wavefunction Calculation

- Input Potential Energy Surface: Eâ‚‘â‚—(R) obtained from electronic structure calculations over a grid of nuclear coordinates

- Construct Nuclear Hamiltonian: Ĥₙ = Tₙ + Eₑₗ(R)

- Solve Nuclear Schrödinger Equation:

- For vibrational states: expand nuclear wavefunction in harmonic oscillator basis or use discrete variable representation

- For rotational states: employ rigid rotor or symmetric top basis functions depending on molecular symmetry

- Apply Eckart Conditions: Separate translational, rotational, and vibrational motions where possible [8]

- Compute Rovibrational Spectrum: From energy level differences and transition dipole moments

Table 2: Mass Ratios and BO Approximation Accuracy for Selected Systems

| System | Lightest Nucleus | Mass Ratio (mâ‚™/mâ‚‘) | Typical BO Error | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H₂⺠| Proton | ~1836 | ~1% [9] | Fundamental studies |

| Câ‚‚ | Carbon-12 | ~21864 | ~0.05% (est.) | Combustion chemistry |

| OHâ» | Oxygen-16 | ~29152 | ~0.03% (est.) | Atmospheric chemistry |

| LiH | Lithium-7 | ~12782 | ~0.07% (est.) | Dipole moment studies [10] |

| Generic organic molecule | Hydrogen | ~1836 | <1% | Drug design, materials |

Breakdown and Limitations of the Approximation

Conditions for BO Approximation Failure

The BO approximation is remarkably successful but fails under specific conditions where electronic and nuclear motions become strongly coupled:

- Conical Intersections: Points where two potential energy surfaces become degenerate, creating funnels for non-adiabatic transitions [11]

- Avoided Crossings: Regions where potential energy surfaces approach closely but do not touch

- Systems with Light Nuclei: Particularly hydrogen-containing systems where nuclear quantum effects are significant

- Electronically Excited States: Where energy gaps between electronic states diminish

The approximation is most reliable when potential energy surfaces are well separated [8]:

$$ E0(\mathbf{R}) \ll E1(\mathbf{R}) \ll E_2(\mathbf{R}) \ll \cdots \text{ for all } \mathbf{R} $$

Non-Adiabatic Processes and Conical Intersections

When the BO approximation breaks down, nuclear motion couples multiple electronic states. The key coupling elements are non-adiabatic coupling terms (NACs) between electronic states Θ and Λ [7]:

$$ \mathbf{g} = \left\langle \Theta \middle| \frac{\partial}{\partial \mathbf{R}} \middle| \Lambda \right\rangle $$

These couplings drive transitions between electronic states, particularly important in:

- Photochemical reactions

- Charge transfer processes

- Collisional quenching of excited states [11]

Protocol 4.2.1: Identifying BO Breakdown in Molecular Dynamics

- Compute Multiple Electronic States: Solve for ground and excited state potential energy surfaces

- Locate Degeneracies: Identify points where Eₑₗ,i(R) ≈ Eₑₗ,j(R)

- Calculate Non-Adiabatic Couplings: Evaluate derivative couplings between states

- Assess Coupling Magnitude: If couplings are large compared to energy separations, BO approximation fails

- Implement Beyond-BO Methods: Use full multiple spawning, surface hopping, or quantum dynamics methods

Advanced Topics and Current Research Frontiers

Beyond Born-Oppenheimer Methodologies

When the BO approximation fails, several advanced methods address non-adiabatic effects:

Born-Huang Expansion: The total wavefunction is expanded as [8]: $$ \Psi(\mathbf{R}, \mathbf{r}) = \sum{k=1}^{K} \chik(\mathbf{r}; \mathbf{R}) \phi_k(\mathbf{R}) $$ This representation includes couplings between electronic states through derivative operators.

Multicomponent Quantum Chemistry: Treats specified quantum mechanically important nuclei (typically protons) on equal footing with electrons, solving the full Schrödinger equation without BO separation [7].

Diabatic Representations: Transform to a basis where nuclear derivative couplings are minimized, often providing more intuitive understanding of reaction pathways.

Research Reagent Solutions for Non-BO Calculations

Table 3: Computational Tools for Beyond-BO Simulations

| Method/Tool | Theoretical Basis | Application Scope | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-Reference CI | Configuration interaction with multiple reference states | Conical intersections, photochemistry | Handles strong electron correlation |

| Non-Adiabatic Molecular Dynamics | Surface hopping, multiple spawning | Excited state dynamics, energy transfer | Explicit treatment of electronic transitions |

| Vibronic Coupling Models | Model Hamiltonians with parameters from ab initio calculations | Jahn-Teller effects, spectroscopic analysis | Computationally efficient for large systems |

| Quantum Monte Carlo | Stochastic solution of Schrödinger equation | Small molecules without BO approximation [10] | Exact treatment of electron-nuclear correlation |

| Full-Dimensional Quantum Dynamics | Grid-based wavepacket propagation | Gas-phase reaction dynamics [11] | Complete quantum treatment of nuclear motion |

Current Research Developments

Recent advances have addressed longstanding challenges:

Molecular Structure Without BO: A Norwegian group successfully recovered the structure of D₃⺠using Monte Carlo approaches without applying the BO approximation [10].

Non-BO Property Calculations: Exact calculations of molecular properties like the dipole moment of LiH have been achieved beyond the BO framework [10].

Stereodynamic Control: Research on non-adiabatic quenching of OH(A²Σâº) by Hâ‚‚ revealed stereodynamic control of reaction pathways, resolved long-standing experiment-theory discrepancies, and demonstrated cases where "theory trumps experiment" [11].

The Born-Oppenheimer approximation remains the cornerstone of modern quantum chemistry, providing both conceptual framework and practical methodology for solving the molecular Schrödinger equation. Its physical basis in the mass disparity between electrons and nuclei justifies the separation of electronic and nuclear motions, enabling the definition of potential energy surfaces and molecular structure. While the approximation fails in specific scenarios involving non-adiabatic processes, continued development of beyond-BO methodologies addresses these limitations. For the vast majority of chemical applications, particularly in ground-state chemistry and drug development, the BO approximation provides sufficiently accurate results with computationally tractable methods. Its central role in connecting fundamental quantum mechanics with chemical phenomena secures its ongoing importance in electronic structure research.

Potential Energy Surfaces, Wavefunctions, and Electron Density

The precise calculation of electronic structure is a cornerstone of quantum chemistry, essential for predicting chemical properties, reactivity, and dynamics. This challenge is fundamentally described by the Schrödinger equation, ( \hat{H}\Psi = E\Psi ), where the Hamiltonian operator (( \hat{H} )) acts on the wavefunction (( \Psi )) to yield the system's energy (( E )) [12]. Solving this equation for many-body systems is computationally intractable, necessitating a suite of approximations and models. The core components for navigating this problem are potential energy surfaces (PESs), which map energy as a function of nuclear coordinates; wavefunctions, which contain all information about the quantum state; and electron density, which, according to the Hohenberg-Kohn theorem, uniquely determines all ground-state properties [13] [14]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to these concepts, framing them within modern research contexts, including machine learning (ML) and high-accuracy ab initio methods, to inform researchers and drug development professionals.

Potential Energy Surfaces (PES)

A Potential Energy Surface (PES) represents the energy of a molecular system as a function of the positions of its atomic nuclei. It provides the foundational landscape upon which chemical dynamics and reactivity are studied.

Theoretical Foundation and Connection to Electronic Structure

The concept of a PES relies on the Born-Oppenheimer approximation, which allows for the separation of electronic and nuclear motion due to the significant mass difference. This approximation states that the total wavefunction can be factorized as ( \Psi{\text{total}} = \Psi{\text{electronic}} \times \Psi{\text{nuclear}} ) [12]. The electronic Schrödinger equation is solved for fixed nuclear positions, generating the electronic energy that contributes to the PES. A critical development in linking electronic motion to nuclear motion on the PES is the integration of Reactive-Orbital Energy Theory (ROET) with electrostatic force theory [15]. This framework identifies "reactive orbitals"—the occupied and unoccupied molecular orbitals with the largest energy changes during a reaction. The electrostatic (Hellmann-Feynman) forces exerted by electrons in these reactive orbitals on the nuclei are calculated as: [ \bf{F}_{A} \simeq Z_{A}\sum\limits{i}^{n_{\rm{elec}}}\bf{f}_{iA} - Z_{A}\sum\limits_{B(\ne A)}^{n_{\rm{nuc}}}}Z_{B}\frac{\bf{R}_{AB}}{R_{AB}^{3}} ] where ( \bf{f}_{iA} ) is the force contribution from the ( i )-th orbital on nucleus A [15]. When these reactive-orbital-based forces align with the reaction direction, they effectively "carve grooves" along the intrinsic reaction coordinate on the PES, directly linking specific electron motions to the pathway of nuclear motion [15].

Advanced Construction Methods: Machine Learning and Δ-ML

Constructing accurate, full-dimensional PESs for polyatomic systems with high-level ab initio methods is computationally prohibitive. Machine learning (ML) offers a powerful solution, with Δ-Machine Learning (Δ-ML) emerging as a particularly cost-effective strategy [16].

The Δ-ML approach constructs a high-level (HL) PES by combining a large set of inexpensive low-level (LL) calculations with a correction term learned from a small number of high-level data points: [ V^{\rm{HL}} = V^{\rm{LL}} + \Delta V^{\rm{HL–LL}} ] The correction term, ( \Delta V^{\rm{HL–LL}} ), is a slowly varying function of atomic coordinates and can be machine-learned from a judiciously chosen, small set of HL configurations [16].

Table 1: Performance of Δ-ML for the H + CH(_4) Reaction

| PES Description | Theoretical Level | Barrier Height (kcal mol(^{-1})) | Reaction Energy (kcal mol(^{-1})) |

|---|---|---|---|

| LL PES (PES-2008) [16] | Analytical VB-MM Functional Form | 15.0 | 2.9 |

| HL Reference (PIP-NN) [16] | UCCSD(T)-F12a/AVTZ | 14.7 | 2.8 |

| Δ-ML PES [16] | PES-2008 + PIP-NN Correction | 14.7 | 2.8 |

| Best Theoretical Estimate [16] | CCSD(T)-F12a with Core/Relativistic | 14.7 | 2.8 |

Experimental Protocol: Δ-ML PES Construction

Objective: To develop a chemically accurate ( ~1 kcal mol(^{-1})) PES for a polyatomic system using the Δ-ML method. System Exemplar: H + CH(4) → H(2) + CH(_3) hydrogen abstraction reaction [16].

- Low-Level Data Generation: Utilize an existing analytical PES (e.g., the PES-2008 surface for H + CH(_4)) or generate a large number (e.g., ~10(^5)) of molecular configurations and compute their energies using a fast, low-level quantum chemical method (e.g., DFTB, HF, or a semi-empirical method).

- High-Level Data Sampling: Select a strategically chosen, smaller subset of configurations (e.g., ~10(^3)) from the LL set. This selection should cover critical regions like reactants, products, transition states, and minimum energy paths.

- HL Single-Point Calculations: Perform single-point energy calculations on the selected configurations using a high-level ab initio method (e.g., UCCSD(T)-F12a with a large basis set).

- Correction Term Learning: For each configuration in the HL subset, compute the energy difference ( \Delta V^{\rm{HL–LL}} = V^{\rm{HL}} - V^{\rm{LL}} ). Train a machine learning model (e.g., a Permutation Invariant Polynomial-Neural Network, PIP-NN) to learn this ( \Delta V^{\rm{HL–LL}} ) correction as a function of molecular geometry.

- HL PES Prediction: For any new nuclear configuration, the predicted HL energy is the sum of its trivially computed LL energy and the ML-predicted correction.

This protocol has been successfully validated for the H + CH(_4) system, with the resulting Δ-ML PES accurately reproducing kinetics and dynamics observables from the reference HL surface [16].

Diagram 1: The Δ-ML workflow for PES construction.

Wavefunctions

The wavefunction, ( \Psi ), is a mathematical function that encapsulates all information about a quantum system. For a molecule, it depends on the coordinates of all electrons and nuclei.

The Born-Oppenheimer Approximation and Molecular Wavefunctions

The full molecular Hamiltonian is given by: [ \hat{H}=\sum\limits{i}^{{n_{\rm{elec}}}}\left(-\frac{1}{2}{\nabla }{i}^{2}-\sum\limits{A}^{{n_{\rm{nuc}}}}}\frac{{Z}{A}}{{r}{iA}}\right)+\sum\limits{i < j}^{{n_{\rm{elec}}}}}\frac{1}{{r}{ij}}+\sum\limits{A < B}^{{n_{\rm{nuc}}}}}\frac{{Z}{A}{Z}{B}}{{R}{AB}} ] The Born-Oppenheimer approximation simplifies this by fixing nuclear coordinates, allowing chemists to solve for the electronic wavefunction, ( \Psi{\text{electronic}} ), at each point on the PES [15] [12]. The square of the wavefunction, ( |\Psi|^2 ), provides the probability density of finding particles in a specific configuration [12].

Orbitals and Reactive Orbital Theory

In independent-electron approximations like Hartree-Fock or Kohn-Sham Density Functional Theory (DFT), the complex many-electron wavefunction is replaced with a set of one-electron functions called orbitals. The total electron density is then constructed from these orbitals: [ \rho({{{{\bf{r}}}}})=\sum\limits{i}^{{n_{\rm{elec}}}}{\phi}{i}^{* }({{{{\bf{r}}}}}){\phi}_{i}({{{{\bf{r}}}}}) ] canonical molecular orbitals have direct physical significance, as their energies correspond to ionization potentials and electron affinities (generalized Koopmans' theorem) [15]. The Reactive Orbital Energy Theory (ROET) leverages this by identifying the specific orbitals—"reactive orbitals"—that undergo the largest energy changes during a reaction. These orbitals are often neither the HOMO nor the LUMO, and the electron transfer between them frequently corresponds to the "curly arrow" representations used by chemists to depict reaction mechanisms [15].

Electron Density

The electron density, ( \rho(\mathbf{r}) ), is a function that describes the probability of finding an electron at a specific point in space. It is a physical observable and a central concept in Density Functional Theory (DFT).

Fundamental Role in Density Functional Theory

The Hohenberg-Kohn theorems establish that the ground-state electron density uniquely determines all properties of a quantum system, including the energy and wavefunction [13] [14]. This makes the electron density a more tractable target for computation than the many-body wavefunction. In Kohn-Sham DFT, the system of interacting electrons is mapped onto a fictitious system of non-interacting electrons that share the same density. The energy can then be expressed as a functional of the density.

Machine Learning for Electron Density Prediction

Recent advances have applied machine learning to predict electron densities directly, dramatically reducing computational cost. A 2025 breakthrough treats the electron density as a 3D grayscale image and uses a convolutional residual network (ResNet) to perform a super-resolution-like transformation from a crude initial guess to an accurate quantum-mechanical density [13] [14].

Input and Model: The model takes as input a crude electron density, typically a simple superposition of atomic densities (SAD guess), represented on a coarse 3D grid. A ResNet architecture then learns to output the accurate molecular electron density on a high-resolution grid.

Performance: This approach has demonstrated state-of-the-art accuracy on the QM9 dataset (134k small organic molecules). The model reduces the density error of the SAD guess by two orders of magnitude, outperforming prior models like ChargE3Net and DeepDFT [13] [14].

Table 2: Accuracy of ML-Predicted Electron Densities and Derived Properties (QM9 Test Set)

| Model / Method | Density Error (Err(_Ï) %) | One-Step DFT Energy MAE (meV) | HOMO Energy MAE (meV) | LUMO Energy MAE (meV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Superposition of Atomic Densities (SAD) [14] | 13.9 | - | - | - |

| ChargE3Net [14] | 0.196 | - | - | - |

| DeepDFT [14] | 0.27 | - | - | - |

| ResNet (This Work) [14] | 0.14 | < 43 | 95 | 93 |

| Direct Gaussian Density Fitting [14] | 0.26 | - | - | - |

Experimental Protocol: Electron Density Prediction via Image Super-Resolution

Objective: To predict an accurate ground-state electron density for a molecule using a machine learning model inspired by image super-resolution.

- Input Generation (Low-Res Image): For a given molecular geometry, generate a crude initial electron density. The most straightforward method is the Superposition of Atomic Densities (SAD), which sums pre-tabulated, spherical neutral atomic densities. This coarse density is featurized on a 3D grid, serving as the low-resolution input "image."

- Model Inference: Pass the gridded, low-resolution density through a pre-trained convolutional ResNet. The model architecture does not explicitly enforce physical symmetries but learns to enhance the resolution and accuracy of the density through its training.

- Output (High-Res Image): The model outputs the predicted electron density on a high-resolution 3D grid (e.g., with a 2x or 4x upscaling factor along each axis).

- Property Calculation (One-Step DFT): Use the predicted density to construct the Kohn-Sham Hamiltonian. A single diagonalization of this Hamiltonian yields the Kohn-Sham orbitals and their energies (HOMO, LUMO), from which the total electronic energy and other properties can be computed. This "one-step DFT" process typically converges in significantly fewer iterations than a full SCF calculation starting from the SAD guess [14].

Diagram 2: ML density prediction and property calculation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools and Concepts

| Item | Function / Description | Exemplary Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Long-Range Corrected DFT (LC-DFT) [15] | A class of density functionals that accurately describe long-range electronic interactions, providing quantitatively accurate canonical orbital energies and shapes. | Calculating accurate reactive orbitals for ROET analysis and establishing the connection between electron motion and electrostatic forces on nuclei [15]. |

| Permutation Invariant Polynomial-Neural Network (PIP-NN) [16] | A machine learning method for constructing PESs that inherently respects the permutation symmetry of identical atoms in a molecule. | Serving as the high-level reference surface or learning the ΔV correction term in Δ-ML for polyatomic systems like H + CH(_4) [16]. |

| Convolutional Residual Network (ResNet) [13] [14] | A deep learning architecture that uses convolutional layers and skip connections, ideal for processing data with grid-like topology (e.g., 3D density grids). | Performing image super-resolution on crude electron densities to predict accurate ground-state quantum mechanical densities [13] [14]. |

| Coupled Cluster Theory (e.g., UCCSD(T)-F12a) [16] [17] | A high-level ab initio electronic structure method that includes electron correlation effects with high accuracy, often considered a "gold standard" for single-reference systems. | Generating benchmark-quality energies for constructing or validating high-fidelity PESs, such as the PIP-NN surface for H + CH(_4) [16]. |

| Superposition of Atomic Densities (SAD) [14] | A crude initial guess for a molecular electron density, generated by summing spherically averaged densities of the constituent atoms. | Providing the low-quality input for the ResNet density prediction model; standard starting point for conventional SCF calculations [14]. |

| Vanillin acetate | 4-Formyl-2-methoxyphenyl acetate | High Purity | 4-Formyl-2-methoxyphenyl acetate is a key synthetic intermediate for pharmaceutical & materials research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| 2,2,2',4'-Tetrachloroacetophenone | 2,2,2',4'-Tetrachloroacetophenone | High Purity | High-purity 2,2,2',4'-Tetrachloroacetophenone for research. A key synthon & photoinitiator. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

The interplay between potential energy surfaces, wavefunctions, and electron density forms the bedrock of the electronic structure problem in quantum chemistry. While these concepts have long been established, current research is revolutionizing their application. The integration of orbital-specific forces bridges the historical gap between electronic and nuclear motion theories, providing a more unified picture of chemical reactivity [15]. Simultaneously, machine learning is reshaping computational workflows. Δ-ML enables the construction of chemically accurate PESs at a fraction of the traditional computational cost [16], while super-resolution-inspired models demonstrate that accurate electron densities—and by extension, all ground-state properties—can be predicted directly from crude initial guesses [13] [14]. These advancements not only enhance predictive capabilities but also deepen our fundamental understanding of the quantum mechanical drivers of chemical phenomena, with profound implications for fields ranging from catalyst design to drug discovery.

The fundamental challenge in quantum chemistry, known as the electronic structure problem, is solving the Schrödinger equation for molecular systems to determine their physical and chemical properties [18]. For any molecule beyond the hydrogen atom, exact analytical solutions are impossible, forcing researchers to develop increasingly sophisticated approximations [18]. This whitepaper traces the evolution of these methodologies from the first quantum mechanical treatment of the chemical bond to modern computational frameworks that enable high-accuracy predictions for complex systems. The journey from Walter Heitler and Fritz London's seminal 1927 work on the hydrogen molecule to today's fragment-based and quantum computing approaches represents a century of innovation in tackling this core problem, with profound implications for materials science, drug discovery, and chemical physics [19] [20].

The Heitler-London Foundation: Birth of Quantum Chemistry

Theoretical Framework and Mathematical Formulation

The 1927 Heitler-London (HL) paper marked the first successful application of quantum mechanics to explain covalent bond formation [20]. Their approach focused on the hydrogen molecule (Hâ‚‚), the simplest neutral molecule, comprising two protons (A and B) and two electrons (1 and 2) [19]. Within the Born-Oppenheimer approximation, which decouples nuclear and electronic motion due to their mass difference, the electronic Hamiltonian in atomic units is [21] [19]:

[ \hat{H} = -\frac{1}{2}\nabla^21 -\frac{1}{2}\nabla^22 - \frac{1}{r{1A}} - \frac{1}{r{1B}} - \frac{1}{r{2A}} - \frac{1}{r{2B}} + \frac{1}{r_{12}} + \frac{1}{R} ]

Heitler and London's key insight was constructing a molecular wavefunction from atomic orbitals to satisfy the Pauli exclusion principle. For the hydrogen molecule's dissociation limit (R→∞), the wavefunction must describe two isolated hydrogen atoms [19]. Their proposed wavefunction was a linear combination of products of 1s atomic orbitals:

[ \psi{\pm}(\vec{r}1, \vec{r}2) = N{\pm}[\phi(r{1A})\phi(r{2B}) \pm \phi(r{1B})\phi(r{2A})] ]

where (\phi(r{ij}) = \sqrt{\frac{1}{\pi}}e^{-r{ij}}) is the hydrogen 1s orbital, and (N_{\pm}) are normalization constants [19]. When combined with appropriate spin functions, this approach produces singlet (bonding) and triplet (antibonding) states [19] [22].

Table: Key Components of the Heitler-London Wavefunction

| Component | Mathematical Form | Physical Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Covalent Terms | (\phi(r{1A})\phi(r{2B})), (\phi(r{1B})\phi(r{2A})) | Each electron localized on different protons |

| Spin Function (Singlet) | (\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}(|\uparrow\downarrow\rangle - |\downarrow\uparrow\rangle)) | Antisymmetric spin state for bonded pair |

| Normalization | (N{\pm} = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2 \pm 2S^2}}) where (S = \int \phi(r{1A})\phi(r_{1B}) d\tau) | Accounts for orbital overlap |

Experimental Protocol and Computational Methodology

The original HL calculation followed a variational approach to estimate the binding energy and bond length of Hâ‚‚ [21] [19]:

- Wavefunction Construction: Prepare the spatial wavefunction ψ₊ for the bonding state

- Energy Calculation: Compute the variational energy (E(R) = \frac{\int \psi \hat{H} \psi d\tau}{\int \psi^2 d\tau}) as a function of internuclear distance R

- Optimization: Find the energy minimum to determine the equilibrium bond length (Râ‚‘) and binding energy (Dâ‚‘)

This protocol yielded qualitative success with Rₑ ≈ 1.7 bohr and Dₑ ≈ 0.25 eV, significantly less than the experimental values of Rₑ = 1.4 bohr and Dₑ = 4.746 eV, but correctly predicted bond formation [21] [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Components for HL Calculations

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for Heitler-London Methodology

| Tool/Concept | Function | Theoretical Basis |

|---|---|---|

| Atomic Orbitals | Basis functions for molecular wavefunction | Hydrogen-like 1s orbitals: (\phi(r) = \sqrt{\frac{1}{\pi}}e^{-r}) |

| Variational Principle | Energy optimization framework | (E{trial} \geq E{exact}) ensures energy improvement |

| Overlap Integral (S) | Quantifies orbital overlap | (S = \int \phi{1A} \phi{1B} d\tau) |

| Coulomb Integral (J) | Electron-proton and electron-electron classical attraction | (J = \int \phi{1A} \phi{2B} \frac{1}{r{12}} \phi{1A} \phi{2B} d\tau1 d\tau_2) |

| Exchange Integral (K) | Quantum mechanical exchange energy | (K = \int \phi{1A} \phi{2B} \frac{1}{r{12}} \phi{1B} \phi{2A} d\tau1 d\tau_2) |

| 2-hexan-3-yloxycarbonylbenzoic acid | 2-hexan-3-yloxycarbonylbenzoic Acid | High-Purity Reagent | 2-hexan-3-yloxycarbonylbenzoic acid is a key reagent for organic synthesis and pharmaceutical research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Tetrabutylammonium diphenylphosphinate | Tetrabutylammonium diphenylphosphinate, CAS:208337-00-2, MF:C28H46NO2P, MW:459.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Methodological Evolution: From HL to Modern Valence Bond Theory

Early Refinements and Theoretical Extensions

The original HL model declined in popularity despite its intuitive appeal, largely due to the computational convenience of molecular orbital (MO) methods [22]. Key limitations included:

- Ionic Terms Omission: The pure covalent wavefunction lacked ionic terms (HâºHâ»)

- Inadequate Electron Correlation: Failed to fully capture how electrons avoid each other

- Computational Complexity: Valence bond calculations were more demanding than early MO approaches

The relationship between VB and MO theory became clearer through mathematical analysis. The simplest MO description of H₂ uses a Slater determinant with doubly-occupied σ orbital [22]:

[ \Phi_{MOT} = |\sigma\overline{\sigma}| \quad \text{where} \quad \sigma = a + b ]

This can be transformed to VB representation [22]:

[ \Phi_{MOT} = (|a\overline{b}| - |\overline{a}b|) + (|a\overline{a}| + |b\overline{b}|) ]

Comparison with the VB wavefunction:

[ \Phi_{VBT} = \lambda(|a\overline{b}| - |\overline{a}b|) + \mu(|a\overline{a}| + |b\overline{b}|) ]

reveals that simple MO theory weights covalent and ionic terms equally (λ = μ), while VB theory optimizes these coefficients, with H₂ having λ ≈ 0.75 and μ ≈ 0.25 [22]. This explains MO theory's poor dissociation behavior, predicting H + H versus the correct H + H dissociation [22].

Diagram: Evolution of Valence Bond Theory from Heitler-London to Modern Approaches

Modern Valence Bond Theory Renaissance

Beginning in the 1980s, valence bond theory experienced a resurgence due to [22] [20]:

- Improved computational algorithms competitive with post-Hartree-Fock methods

- Better programming approaches by Gerratt, Cooper, Karadakov, and Raimondi

- Sophisticated wavefunctions using delocalized atomic orbitals or fragment molecular orbitals

Modern VB theory now produces accuracy comparable to high-level MO methods while retaining the intuitive appeal of localized bonds [22]. Recent work by Shaik, Hiberty, and others has demonstrated VB's particular value in understanding chemical reactivity and bond formation [20].

Parallel Development: Molecular Orbital Theory and Computational Frameworks

Hartree-Fock Method and Basis Sets

As VB theory developed, molecular orbital theory emerged as a competing framework with distinct advantages for computation [18]. The central approximation is the Slater determinant wavefunction:

[ \Psi = \frac{1}{\sqrt{N!}} \begin{vmatrix} \chi1(x1) & \chi2(x1) & \cdots & \chiN(x1) \ \chi1(x2) & \chi2(x2) & \cdots & \chiN(x2) \ \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \ \chi1(xN) & \chi2(xN) & \cdots & \chiN(xN) \end{vmatrix} ]

where χᵢ are spin orbitals, typically constructed as linear combinations of atomic orbitals (LCAO):

[ \phii(\vec{r}) = \sum{\mu} c{\mu i} \chi{\mu}(\vec{r}) ]

The choice of basis functions {χₚ} constitutes the basis set, with modern calculations typically using Gaussian-type orbitals for computational efficiency [18]. The 6-31G* basis set, for example, uses six Gaussians for core orbitals and split-valence (3+1 Gaussians) for valence orbitals, plus polarization functions [18].

Table: Comparison of Quantum Chemical Methods for Hâ‚‚ Calculation

| Method | Wavefunction Approach | Binding Energy (eV) | Bond Length (bohr) | Electron Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heitler-London (1927) | Covalent VB | 0.25 | 1.7 | Partial |

| Hartree-Fock (LCAO-MO) | Single Slater determinant | 3.49 | 1.38 | None |

| Modern VB with screening | Variational VB with optimized charge | ~4.5 | ~1.41 | Improved |

| Experimental Hâ‚‚ | - | 4.746 | 1.40 | Full |

Density Functional Theory and Electron Correlation

Density Functional Theory (DFT) represents a different approach, using electron density rather than wavefunctions as the fundamental variable [18]. The Hohenberg-Kohn theorems establish that [18]:

- The ground state electron density uniquely determines all system properties

- An energy functional exists that is minimized by the exact ground state density

In practice, Kohn-Sham DFT reintroduces orbitals to compute the kinetic energy accurately but faces challenges with the unknown exchange-correlation functional [18].

Modern Computational Frameworks and Methodologies

Fragment-Based Quantum Chemistry

To address the exponential scaling of quantum chemical calculations, fragment-based methods partition large systems into smaller subsystems [23]. The FRAGMENT software framework provides open-source implementation of these approaches with these capabilities [23]:

- Automatic fragmentation of large biomolecules and materials

- Distance- and energy-based screening to reduce computational cost

- Database management for storing and querying calculation results

- Interfaces to multiple quantum chemistry engines (Q-Chem, PySCF, ORCA, etc.)

This methodology enables calculations on systems with thousands of atoms by solving numerous smaller problems and combining their solutions [23].

Quantum Computing and Quantum Algorithms

Quantum computing represents a potential paradigm shift for quantum chemistry, with chemical problems likely to be among the first practical applications [24]. Current developments include [24]:

- Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE): A hybrid quantum-classical algorithm for estimating molecular ground states

- Chemical dynamics simulations: Modeling how molecular structure evolves over time

- Protein folding studies: 12-amino-acid chain folding demonstrated on quantum hardware

While current quantum computers lack sufficient qubits (∼100) for practical chemical applications—estimates suggest 100,000+ qubits needed for cytochrome P450 enzymes—algorithm development continues advancing [24].

Diagram: Computational Frameworks in Quantum Chemistry

Advanced Protocols: Screening-Modified Heitler-London Model

Contemporary Enhancement of Classical Approach

Recent work (2025) has revisited the HL model with a screening modification that substantially improves accuracy [19]. The protocol involves:

Wavefunction Modification: Introduce an effective nuclear charge parameter α to the atomic orbitals: ϕ(rᵢⱼ) = √(1/π) e^(-αrᵢⱼ)

Variational Optimization: For each internuclear distance R, optimize α using variational quantum Monte Carlo (VQMC) methods

Function Development: Construct α(R) as a function of R to create an analytically simple variational wavefunction

This screening-modified HL approach yields significantly improved agreement with experimental bond length (Rₑ ≈ 1.41 bohr) and dissociation energy, demonstrating how classical methods can be enhanced with modern computational techniques [19].

VQMC Methodology for HL Screening

The variational quantum Monte Carlo protocol for optimizing the screening parameter [19]:

Trial Wavefunction Preparation: ψ₊(r⃗â‚, r⃗₂) = Nâ‚Š[Ï•â‚(râ‚â‚)Ï•â‚(râ‚‚â‚) + Ï•â‚(râ‚â‚)Ï•â‚(râ‚‚â‚)] with Ï•â‚(rᵢⱼ) = √(α³/Ï€) e^(-αrᵢⱼ)

Energy Evaluation: E(α, R) = ∫ ψ₊(r⃗â‚, r⃗₂) Ĥ ψ₊(r⃗â‚, r⃗₂) dr⃗â‚dr⃗₂ / ∫ ψ₊²(r⃗â‚, r⃗₂) dr⃗â‚dr⃗₂

Stochastic Optimization: Use Metropolis-Hastings sampling to compute integrals and optimize α to minimize E(α, R)

This approach maintains the conceptual simplicity of the HL model while achieving accuracy competitive with more sophisticated methods [19].

The journey from Heitler-London's pioneering work to modern computational frameworks demonstrates both the remarkable progress in quantum chemistry and the enduring value of foundational physical insights. As we enter the International Year of Quantum Science and Technology (2025), marking a century since the development of quantum mechanics, the electronic structure problem continues to drive methodological innovation [25]. Future directions include [19] [24] [23]:

- Hybrid quantum-classical algorithms for practical quantum computing applications

- Machine learning potentials trained on quantum chemical data

- Multiscale modeling connecting electronic structure to mesoscale phenomena

- Improved density functionals with better accuracy for correlated systems

For drug development professionals and researchers, understanding this methodological evolution is crucial for selecting appropriate computational tools and interpreting their results. The complementary strengths of valence bond, molecular orbital, and density functional approaches provide a rich toolkit for tackling the electronic structure problem across diverse chemical systems.

The central challenge in quantum chemistry fundamentals research lies in accurately and efficiently predicting molecular structure, stability, and reactivity from first principles. These three pillars are interconnected manifestations of the electronic structure problem—solving the Schrödinger equation for many-body systems. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to contemporary computational methods addressing this challenge. We detail theoretical frameworks spanning from ab initio quantum chemistry and density functional theory to emerging machine learning and quantum computing approaches. The document synthesizes advanced protocols for conformational sampling, stability analysis, and reactivity mapping, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a rigorous toolkit for molecular design and discovery.

The foundational goal of quantum chemistry is to solve the electronic Schrödinger equation for molecular systems. This electronic structure problem is paramount because the spatial distribution and energies of electrons determine a molecule's equilibrium geometry (structure), its resilience to perturbation (stability), and its propensity to undergo chemical transformation (reactivity). The intrinsic coupling of these properties means that accurate predictions require a quantum mechanical treatment of electron correlation, a computationally daunting task for all but the smallest molecules. The core challenge is to develop methods that offer a balanced trade-off between computational cost and predictive accuracy, enabling the study of chemically relevant systems such as drug candidates and catalytic materials. This guide details the computational frameworks and experimental protocols that are closing the gap between theoretical prediction and experimental observation in molecular science.

Computational Frameworks for Molecular Prediction

The computational chemist's arsenal has expanded beyond traditional quantum chemical methods to include hybrid classical-quantum and machine learning approaches. The selection of a method involves a critical balance between computational cost and the level of accuracy required for the specific chemical question.

Table 1: Computational Methods for Molecular Property Prediction

| Method Category | Key Methods | Theoretical Basis | Applicability to Structure, Stability, Reactivity | Computational Scaling |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ab Initio Wavefunction | Hartree-Fock (HF), Møller-Plesset Perturbation Theory (MP2), Coupled Cluster (e.g., CCSD(T)) | Approximates solution to electronic Schrödinger equation [26] [27]. | High Accuracy for stability (energies) and reactivity (barriers); reference for other methods. | HF: O(Nâ´), MP2: O(Nâµ), CCSD(T): O(Nâ·) |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | B3LYP, ωB97X-D, with dispersion corrections (DFT-D3, DFT-D4) | Uses electron density as fundamental variable; functionals define exchange-correlation energy [26]. | Good Balance for geometry optimization, global reactivity descriptors (HOMO-LUMO gap), and reaction paths [28]. | O(N³) |

| Multiconfigurational Methods | Complete Active Space SCF (CASSCF) | Accounts for non-dynamical electron correlation crucial for bonds and excited states [26] [29]. | Essential for photochemistry, diradicals, and transition metals where single-reference DFT/CC fail. | O(exp(N)) |

| Machine Learning (ML) | Stereoelectronics-Infused Molecular Graphs (SIMGs), Neural Network Potentials | Learns structure-property relationships from quantum chemical data [26] [30]. | Rapid Prediction of properties and generation of plausible 3D conformations (e.g., StoL framework) [31]. | O(1) after training |

| Quantum Computing Algorithms | Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE), Quantum Phase Estimation (QPE) | Uses qubits to represent molecular wavefunction; aims for exact solution [26]. | Proof-of-concept for small molecules (Hâ‚‚, LiH); potential for exponential speedup on complex systems [32]. | Polynomial on quantum hardware (theoretically) |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

This section provides detailed, actionable protocols for key computational experiments aimed at predicting molecular structure, stability, and reactivity.

Protocol 1: Generating Molecular Conformations with the StoL Framework

The StoL (Small-to-Large) framework is a generative diffusion model that rapidly produces diverse and chemically valid 3D conformations for large molecules using knowledge learned from smaller fragments [31]. This is critical for applications like virtual screening in drug discovery.

Detailed Workflow:

Input and Fragmentation:

- Provide the molecule's SMILES string as input.

- Systematically decompose the large molecule into smaller, chemically valid fragments using predefined rules (e.g., breaking at rotatable bonds or specific functional groups) [31].

Fragment Conformation Generation:

- Process each fragment through a chemistry-enhanced diffusion model. This model, trained exclusively on databases of small molecules, generates multiple plausible 3D Cartesian coordinates for each fragment [31].

- Apply rapid geometric filtering based on chemical principles (e.g., disallowing impossibly short interatomic distances or strained bond angles) to eliminate unphysical structures immediately [31].

Assembly and Validation:

- Reassemble the validated fragment conformations into a complete large-molecule structure.

- Perform a final chemistry-constrained validation to ensure the overall geometry is structurally sound and thermodynamically meaningful. This step may involve low-level quantum mechanical calculations or rule-based checks [31].

The following diagram visualizes this "small-to-large" assembly process:

Protocol 2: Analyzing Stability and Reactivity via Density Functional Theory

This protocol uses DFT to compute electronic properties that govern molecular stability and chemical reactivity, using the study of cirsilineol as an exemplar [28].

Detailed Workflow:

Geometry Optimization and Conformational Analysis:

- Method: Use a hybrid functional like B3LYP and a polarized, diffuse basis set such as 6-311++G(d,p) [28].

- Procedure: Perform a potential energy surface (PES) scan to identify all low-energy conformers. Select the global minimum energy structure for all subsequent analyses. For cirsilineol, this resulted in a final energy of -767,080.1261 kcal/mol [28].

Electronic Structure and Stability Analysis:

- Natural Bond Orbital (NBO) Analysis: Calculate second-order perturbation theory stabilization energies to identify key hyperconjugative interactions (e.g., LP(O) → π*(C-C)). A high stabilization energy (e.g., 73.08 kcal/mol) indicates a significant contribution to molecular stability [28].

- Quantum Theory of Atoms in Molecules (QTAIM): Analyze the electron density at bond critical points (BCPs) to characterize intra- and intermolecular interactions, such as hydrogen bonding. The H31…O5 interaction in cirsilineol was identified as the strongest [28].

- Non-Covalent Interaction (NCI) Analysis: Visualize and quantify weak repulsive and attractive interactions (van der Waals, steric clashes) via the reduced density gradient (RDG) isosurfaces [28].

Global and Local Reactivity Descriptor Calculation:

- HOMO-LUMO Analysis: Perform a single-point energy calculation on the optimized geometry to obtain the energies of the Highest Occupied and Lowest Unoccupied Molecular Orbitals. The HOMO-LUMO gap (ΔE_L-H) is a key indicator of kinetic stability and chemical hardness [28].

- Fukui Functions: Use finite difference approximations on electron densities from calculations of the neutral, cationic, and anionic species to map local electrophilic and nucleophilic sites, identifying chemical reactive hotspots [28].

The logical flow of this DFT-based analysis is shown below:

Protocol 3: Quantum Machine Learning with Molecular Structure Encoding (QMSE)

The QMSE scheme is a advanced protocol for embedding molecular information into quantum circuits for enhanced machine learning tasks like property prediction [33].

Detailed Workflow:

Construct the Hybrid Coulomb-Adjacency Matrix:

- Create a matrix that integrates both topological connectivity (the adjacency matrix from the molecular graph, weighted by bond orders) and through-space electrostatic interactions (approximated by a Coulomb matrix) [33].

Encode the Matrix into a Quantum Circuit:

- Map the elements of the hybrid matrix directly into parameterized one- and two-qubit rotation gates (e.g., Rz, Rxx) to create the data-encoding quantum circuit. This creates a graph state that physically represents the molecule's structure in Hilbert space [33].

Execute the QML Model:

- This encoded state is then fed into a parameterized quantum neural network (QNN) ansatz.

- Train the entire model (encoding and ansatz parameters) on a molecular dataset (e.g., for boiling point regression or state phase classification) using a hybrid quantum-classical optimizer [33].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

This section details the key computational "reagents" and software tools required for research in this field.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions in Computational Chemistry

| Tool Category | Item/Software | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Electronic Structure Codes | Psi4, PySCF, ORCA, Gaussian | Software packages that implement ab initio, DFT, and semi-empirical methods for energy and property calculations [27] [28]. |

| Force Fields & Molecular Mechanics | AMBER, CHARMM, OPLS | Parameterized classical potentials for simulating large systems (proteins, solvents) over long timescales via molecular dynamics [26]. |

| Machine Learning Libraries | PyTorch, TensorFlow, JAX | Frameworks for developing and training neural network potentials (e.g., for SIMGs [30]) and generative models (e.g., StoL [31]). |

| Quantum Computing SDKs | Qiskit, Cirq, PennyLane | Toolkits for building, simulating, and running quantum algorithms like VQE for molecular electronic structure problems [32] [26]. |

| Chemical Databases | ChEMBL, Cambridge Structural Database (CSD) | Curated repositories of experimental bioactivity data and 3D structures for training and validating ML and QM models [31] [26]. |

| Analysis & Visualization | Multiwfn, VMD, Jmol | Specialized software for analyzing results from QTAIM, NCI, NBO, and visualizing molecular orbitals, densities, and dynamics [28]. |

| Diisopropyl chloromalonate | Diisopropyl Chloromalonate | High Purity | RUO Supplier | Diisopropyl chloromalonate: A versatile chloromalonate ester for organic synthesis & peptide mimicry. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

| 2-Chloro-3-hydroxy-1,4-naphthoquinone | 2-Chloro-3-hydroxy-1,4-naphthoquinone | High Purity | High-purity 2-Chloro-3-hydroxy-1,4-naphthoquinone for research applications. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |