Strategies for Molecular System Measurement Overhead Reduction: From Quantum Algorithms to Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of innovative strategies for reducing measurement overhead in the computational study of molecular systems, a critical bottleneck for researchers and drug development professionals.

Strategies for Molecular System Measurement Overhead Reduction: From Quantum Algorithms to Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of innovative strategies for reducing measurement overhead in the computational study of molecular systems, a critical bottleneck for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational concepts of measurement overhead, presents cutting-edge methodological advances from quantum computation and artificial intelligence, offers practical troubleshooting and optimization techniques, and delivers rigorous validation frameworks. By synthesizing the latest research, this guide aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to accelerate molecular simulations, enhance the precision of energy estimations, and ultimately streamline the path from computational discovery to clinical application.

Understanding Measurement Overhead: The Fundamental Bottleneck in Molecular Simulation

Defining Measurement Overhead in Computational Molecular Science

In computational molecular science, measurement overhead encompasses the quantum and classical resources required to estimate physical observables, such as molecular energies, to a desired precision. This overhead is a critical bottleneck in fields like drug development and materials design, where high-accuracy energy calculations are essential. For near-term quantum hardware, this includes the number of measurement shots, circuit repetitions, and qubit resources needed to overcome inherent hardware noise and algorithmic constraints [1]. Effectively reducing this overhead is a central challenge for making quantum computational chemistry practical on current devices.

This guide objectively compares three dominant strategies for reducing measurement overhead: informationally complete quantum measurements, hybrid quantum-neural wavefunction methods, and error suppression and mitigation techniques. We present supporting experimental data, detailed protocols, and key research tools to inform researchers and scientists in selecting the most appropriate strategy for their specific molecular system.

Core Concepts of Measurement Overhead

Measurement overhead in quantum computational chemistry arises from several interconnected factors:

- Shot Overhead: The number of times (

N_shots) a quantum circuit must be executed and measured to estimate an observable's expectation value to a specified statistical precision (e.g., chemical precision of 1.6x10â»Â³ Hartree) [1]. This is often the most dominant cost. - Circuit Overhead: The number of distinct quantum circuits (

N_circuits) that must be compiled and executed, for instance, to measure different Pauli terms of a molecular Hamiltonian [1] [2]. - Readout Error: Inaccurate qubit measurements at the end of a circuit execution (e.g., on the order of 10â»Â² on current hardware), which can introduce significant bias into estimates if not mitigated [1].

- Classical Post-processing: The computational cost of mitigating errors and computing expectation values from the raw quantum measurement data [3] [4].

Comparative Analysis of Measurement Overhead Reduction Strategies

The following table summarizes the quantitative performance and characteristics of three leading strategies for managing measurement overhead.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Measurement Overhead Reduction Strategies

| Strategy | Reported Performance & Overhead Reduction | Key Mechanism | Compatible Workloads | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Informationally Complete (IC) Measurements [1] [2] | Error reduction from 1-5% to 0.16% (near chemical precision) on a 28-qubit system; Enables commutator estimation without additional quantum measurements [1] [2] | Uses generalized (POVM) measurements to enable unbiased estimation via Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT) and reuse of data for multiple observables [1]. | Estimation tasks (e.g., energy estimation in VQE, ADAPT-VQE); Systems with complex observables [2]. | Requires accurate characterization of detector noise; Overhead in implementing generalized measurements. |

| Hybrid Quantum-Neural Wavefunctions (pUNN) [3] | Achieves near-chemical accuracy for systems like Nâ‚‚ and CHâ‚„; Retains low qubit count (N) and shallow circuit depth of pUCCD [3]. | Combines a shallow quantum circuit (pUCCD) with a classical neural network to represent the molecular wavefunction, avoiding costly quantum state tomography [3]. | Ground and excited state energy calculations; Strongly correlated systems where high expressivity is needed [3]. | Classical training overhead of the neural network; Scaling of neural network parameter count with system size. |

| Error Suppression & Mitigation [4] | Deterministic error suppression without runtime penalty; Error mitigation (e.g., PEC) provides accuracy guarantees but with exponential runtime overhead [4]. | Error suppression proactively avoids noise via circuit compilation. Error mitigation (e.g., ZNE, PEC) uses post-processing and repeated circuit executions to average out noise [4]. | Error suppression: Any application. Error mitigation: Primarily estimation tasks (not sampling of full distributions) [4]. | Error mitigation is incompatible with algorithms requiring full output distributions; Exponential overhead can be prohibitive for large workloads [4]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and provide a clear framework for benchmarking, this section outlines the core experimental methodologies for the featured strategies.

Protocol for IC Measurements with Quantum Detector Tomography

This protocol, as implemented for the BODIPY molecule on IBM quantum hardware, demonstrates how to achieve high-precision energy estimation [1].

- State Preparation: Prepare the target quantum state (e.g., the Hartree-Fock state) on the quantum processor. Using a simple state like Hartree-Fock isolates measurement errors from gate errors [1].

- Locally Biased Random Measurements:

- Define a set of informationally complete measurement settings biased towards the Pauli strings of the target molecular Hamiltonian.

- For each setting, apply the corresponding unitary rotation to the state.

- Perform

Tshots (T = 8192in the reference experiment) for each setting [1].

- Parallel Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT):

- Interleave circuits for performing QDT with the measurement circuits in a blended scheduling pattern.

- This characterizes the noisy measurement effects (POVMs) of the device concurrently with the main experiment, mitigating the impact of time-dependent noise [1].

- Classical Post-Processing:

- Use the characterized noisy POVMs from QDT to construct an unbiased, linear estimator for the expectation value of the Hamiltonian.

- The informationally complete nature of the data allows for the estimation of all Hamiltonian terms simultaneously [1].

Protocol for Hybrid Quantum-Neural Wavefunction (pUNN)

The pUNN method provides a framework for accurate energy calculations with low quantum resource requirements [3].

- Quantum Circuit Execution:

- Prepare the seniority-zero wavefunction using the paired UCCD (pUCCD) ansatz on

Nqubits. - Apply an entanglement circuit

Ê(e.g.,Nparallel CNOT gates) between theNoriginal qubits andNancilla qubits. - Apply a low-depth perturbation circuit (e.g., single-qubit

R_yrotations with small angles) to the ancilla qubits to introduce contributions from outside the seniority-zero subspace [3].

- Prepare the seniority-zero wavefunction using the paired UCCD (pUCCD) ansatz on

- Neural Network Processing:

- For each measurement shot, the resulting bitstring

|k> ⊗ |j>(from original and ancilla registers) is fed into a fully-connected neural network. - The neural network outputs a coefficient

b_kjthat modulates the amplitude of the quantum state, enhancing its expressivity. - A particle-number-conserving mask is applied to the output to ensure physicality [3].

- For each measurement shot, the resulting bitstring

- Expectation Value Calculation:

- The expectation values of the Hamiltonian,

<Ψ|Ĥ|Ψ>and the norm<Ψ|Ψ>, are computed efficiently using a combination of the quantum measurement outcomes and the neural network outputs, without the need for quantum state tomography [3].

- The expectation values of the Hamiltonian,

Visualizing Measurement Overhead Reduction Workflows

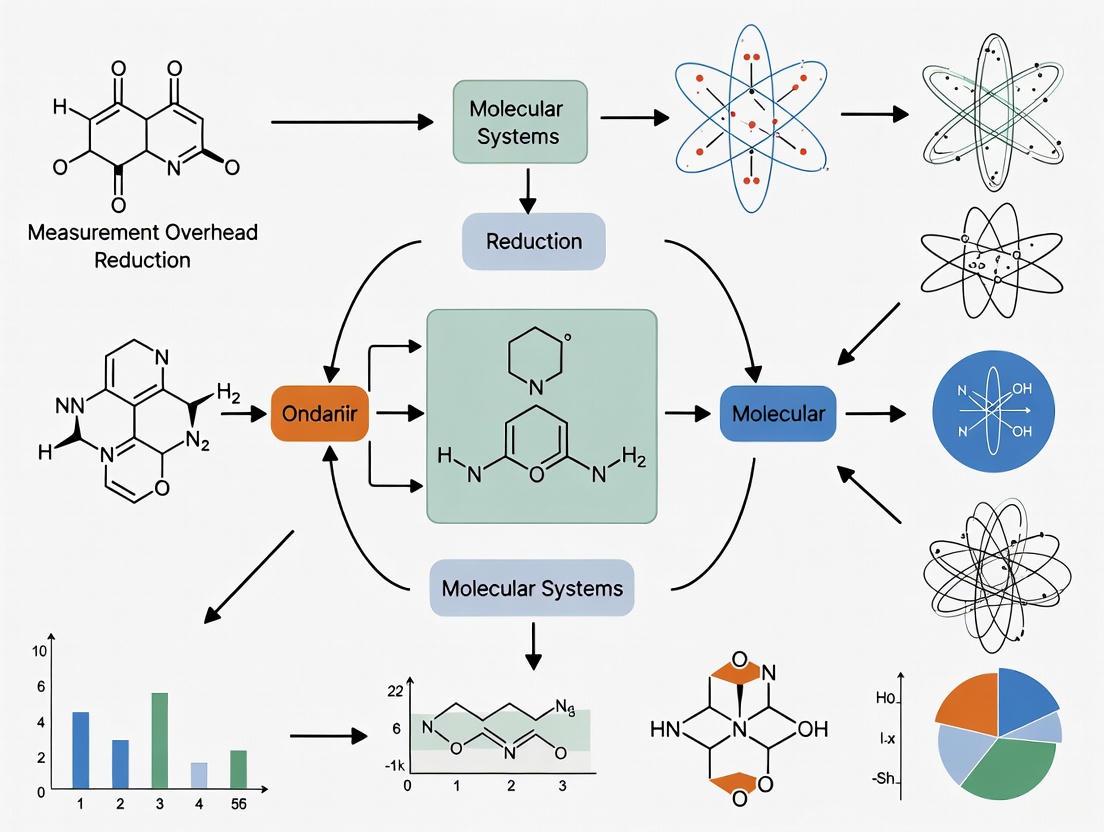

The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence and key components of the two primary quantum-focused strategies discussed in this guide.

Diagram 1: Workflows for IC and Hybrid Quantum-Neural Strategies.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

This section details the key computational tools and frameworks that function as the essential "reagents" for experiments in quantum computational chemistry and measurement overhead reduction.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Molecular Quantum Simulations

| Research Reagent (Tool/Framework) | Primary Function | Relevance to Overhead Reduction |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT) | Characterizes the actual noisy measurement process (POVMs) of a quantum device [1]. | Enables the construction of unbiased estimators, directly mitigating readout error and reducing the shot overhead required for accurate results [1]. |

| Locally Biased Classical Shadows | A technique for selecting random measurement settings informed by the target Hamiltonian [1]. | Reduces shot overhead by prioritizing measurements that have a larger impact on the final energy estimation [1]. |

| Blended Scheduling | An execution strategy that interleaves different types of circuits (e.g., main experiment and QDT) over time [1]. | Mitigates the impact of time-dependent noise (drift), ensuring consistent measurement error across an entire experiment and improving the reliability of error mitigation [1]. |

| Hybrid Quantum-Neural Wavefunction (pUNN) | A computational framework combining a parameterized quantum circuit with a classical neural network to represent a molecular state [3]. | Reduces quantum circuit depth and qubit count requirements while maintaining high accuracy, thus lowering both quantum hardware requirements and associated measurement overhead [3]. |

| Error Suppression Software (e.g., Q-CTRL) | Software tools that proactively minimize noise in quantum circuits at compile-time via pulse-level control and optimized compilation [4]. | Reduces the overall error rate before measurement, which in turn lowers the burden on subsequent error mitigation techniques and reduces the shot overhead needed to achieve a target precision [4]. |

| Fumonisin B3 | Fumonisin B3, CAS:1422359-85-0, MF:C34H59NO14, MW:705.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Daphnicyclidin I | Daphnicyclidin I|CAS 1467083-10-8|Alkaloid | Daphnicyclidin I, a natural Daphniphyllum alkaloid for cancer research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

The choice of an optimal strategy for reducing measurement overhead is not one-size-fits-all but depends critically on the specific molecular problem, available quantum hardware, and classical computational resources.

- For researchers focusing on accurate molecular energy estimation using near-term quantum devices, informationally complete measurements combined with QDT provide a robust path to achieving near-chemical precision, as demonstrated on complex systems like BODIPY [1].

- For problems where classical computational resources are plentiful but quantum resources are scarce or noisy, hybrid quantum-neural wavefunctions offer a promising route to high accuracy with low quantum overhead [3].

- Error suppression should be considered a universal first step for any quantum application, while error mitigation is a powerful but costly tool best reserved for estimation tasks with low circuit counts [4].

As quantum hardware continues to evolve, the development of increasingly sophisticated techniques for mitigating measurement overhead will remain a cornerstone for realizing the potential of quantum computing in drug development and molecular science.

For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working in molecular systems research, quantum computing presents a transformative potential—and a significant overhead management challenge. On near-term noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices, three categories of overhead dominate practical implementations: shot overhead (the number of repeated circuit executions for statistical precision), circuit overhead (the number of distinct circuit configurations required), and computational cost (classical processing requirements). These overheads collectively determine the feasibility and scalability of quantum computational chemistry applications, from molecular energy estimation to drug discovery pipelines. This guide objectively compares current strategies for mitigating these overheads, providing experimental data and methodologies to inform research planning and implementation.

Comparative Analysis of Overhead Reduction Techniques

The table below synthesizes experimental data from recent studies on overhead reduction techniques, highlighting their effectiveness against different overhead types and implementation requirements.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Quantum Overhead Reduction Techniques

| Technique | Primary Overhead Targeted | Reported Effectiveness | Implementation Requirements | Key Applications Demonstrated |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Informationally Complete (IC) Measurements with QDT [1] | Shot, Circuit | Error reduction from 1-5% to 0.16%; Enables reuse of measurement data | Quantum detector tomography; Parallel execution | Molecular energy estimation (BODIPY); Ground, first excited singlet (S1), and triplet (T1) state calculations |

| Locally Biased Random Measurements [1] | Shot | Significant reduction in shots required while maintaining precision | Hamiltonian-structure analysis; Classical post-processing | Measurement of complex Hamiltonians with many Pauli strings (e.g., 8-28 qubit systems) |

| AIM-ADAPT-VQE [2] [5] | Measurement (Shot & Circuit) | Enables ADAPT-VQE with no additional measurement overhead; High convergence probability | Informationally complete POVMs; Classical post-processing | H4 molecular chains; 1,3,5,7-octatetraene Hamiltonians |

| Blended Scheduling [1] | Time-dependent noise | Mitigates temporal noise variations across experiments | Temporal interleaving of circuit types | Molecular energy estimation on IBM Eagle r3 processors |

| ShotQC Framework [6] | Sampling (Shot) | Up to 19x reduction in sampling overhead (avg. 2.6x economical) | Circuit cutting; Adaptive Monte Carlo; Cut parameterization | Benchmark circuit simulations across multiple subcircuits |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

High-Precision Molecular Energy Estimation with IC Measurements

Objective: Achieve chemical precision (1.6×10â»Â³ Hartree) in molecular energy estimation despite high readout errors (~10â»Â²) on near-term hardware [1].

Methodology:

- System Preparation: Prepare Hartree-Fock states of BODIPY-4 molecule across active spaces of 4e4o (8 qubits) to 14e4o (28 qubits). Hartree-Fock states are selected as they are separable and avoid two-qubit gate errors, isolating measurement errors.

- Informationally Complete Measurements: Implement IC positive operator-valued measures (POVMs) allowing estimation of multiple observables from the same measurement data.

- Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT): Perform parallel QDT to characterize and mitigate readout errors. This involves:

- Sampling S = 7×10ⴠdifferent measurement settings

- Repeating each setting T = 100 times

- Using noisy measurement effects to build an unbiased estimator

- Locally Biased Measurements: Employ Hamiltonian-inspired biased sampling to prioritize measurement settings with greater impact on energy estimation.

- Blended Scheduling: Temporally interleave circuits for different molecular states (S0, S1, T1) and QDT to average out time-dependent noise.

Key Parameters: The Hamiltonians contained 47,420 Pauli strings across all active spaces, presenting substantial measurement challenges [1].

AIM-ADAPT-VQE for Measurement-Efficient Ansatz Construction

Objective: Implement ADAPT-VQE without the prohibitive measurement overhead typically associated with gradient evaluations [2] [5].

Methodology:

- Energy Evaluation: Perform adaptive informationally complete generalized measurements (AIM) to obtain the energy expectation value.

- Data Reuse: Utilize the same IC measurement data to classically estimate all commutators required for the ADAPT-VQE operator pool selection.

- Iterative Ansatz Construction:

- For each iteration, use the already collected data to compute gradients

- Select the operator with the largest gradient magnitude

- Grow the ansatz circuit with corresponding unitary

- Convergence Check: Continue until energy convergence criteria are met, typically to chemical precision.

Validation: Applied to H4 hydrogen chains and 1,3,5,7-octatetraene molecules, demonstrating convergence to ground states with no additional quantum measurements beyond initial energy estimation [5].

ShotQC for Sampling Overhead Reduction in Circuit Cutting

Objective: Reduce exponential sampling overhead in quantum circuit cutting, which enables large circuit simulation across distributed smaller quantum devices [6].

Methodology:

- Circuit Partitioning: Divide large quantum circuits into smaller subcircuits using tensor network representation.

- Shot Distribution Optimization: Implement adaptive Monte Carlo method to dynamically allocate shot counts to subcircuits based on their contribution to final variance.

- Cut Parameterization: Leverage additional degrees of freedom in mathematical identities used during postprocessing to minimize variance.

- Reconstruction: Classically recombine subcircuit results using the optimized parameters and shot distributions.

Performance Metrics: Benchmarking demonstrated 19x maximum reduction in sampling overhead, with economical settings providing 2.6x average reduction without increasing classical postprocessing complexity [6].

Interrelationships Between Overhead Reduction Strategies

The diagram below illustrates the logical relationships between different overhead sources and the techniques that address them, showing how an integrated approach can collectively reduce quantum computational costs.

Diagram 1: Logical relationships between quantum overhead types, reduction techniques, and their primary applications.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Methods and Computational Tools for Quantum Overhead Reduction

| Tool/Method | Function | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Informationally Complete POVMs | Enables estimation of multiple observables from single measurement dataset; Allows quantum detector tomography | Requires careful calibration but enables significant data reuse; Compatible with various hardware platforms |

| Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT) | Characterizes and mitigates readout errors; Builds unbiased estimators from noisy measurement effects | Requires parallel execution alongside main circuits; Needs 7×10ⴠsettings × 100 repeats for high precision [1] |

| Hamiltonian-Inspired Biased Sampling | Reduces shot requirements by prioritizing impactful measurements | Maintains informational completeness while reducing shots by ~30-50% [1] |

| Blended Scheduling | Mitigates time-dependent noise by interleaving circuit types | Ensures homogeneous noise distribution across comparative experiments [1] |

| Adaptive Monte Carlo Shot Allocation | Dynamically distributes shots to subcircuits based on variance contribution | Reduces sampling overhead by up to 19x in circuit cutting applications [6] |

| Tensor Network Circuit Representation | Enables circuit cutting and classical optimization | Foundation for ShotQC and related circuit partitioning approaches [6] |

| Scutebata A | Scutebata A (RUO) | Scutebata A, a neo-clerodane diterpenoid from Scutellaria barbata. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

| Lycoclavanol | Lycoclavanol, MF:C30H50O3, MW:458.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The comparative data presented in this guide demonstrates that while distinct overhead reduction strategies target different aspects of quantum computational cost, their integration provides the most promising path toward practical quantum computational chemistry. Techniques like IC measurements with QDT and AIM-ADAPT-VQE show particular promise for molecular energy estimation and ansatz construction, achieving error reductions from 1-5% to near-chemical precision (0.16%) [1]. For drug development professionals and molecular systems researchers, these overhead management strategies significantly enhance the feasibility of deploying quantum computations for practical problems including molecular screening, reaction pathway analysis, and excited state calculations. As hardware continues to evolve, the systematic addressing of shot, circuit, and computational overheads will remain critical to realizing quantum advantage in molecular systems research.

The Impact of Overhead on Scalability and Precision in Drug Discovery

In modern drug discovery, measurement overhead—encompassing computational time, experimental resources, and data acquisition costs—directly impacts both the scalability of research pipelines and the precision of outcomes. Effectively managing this overhead is critical for advancing from target identification to clinical candidate selection. This guide objectively compares leading computational strategies, focusing on their methodologies, performance metrics, and suitability for different stages of the discovery pipeline. The analysis is framed within the broader thesis of measurement overhead reduction across molecular systems research, providing scientists with a data-driven framework for selecting optimal tools.

Comparative Analysis of Computational Platforms

The table below summarizes the core performance metrics and overhead characteristics of five leading computational approaches, based on recent experimental data.

Table 1: Performance and Overhead Comparison of Drug Discovery Platforms

| Platform / Method | Reported Accuracy | Computational/Measurement Overhead | Key Scalability Advantage | Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hybrid Quantum-Neural (pUNN) [3] | Near-chemical accuracy | Shallow quantum circuit depth (N qubits); Resilient to hardware noise | Efficient measurement protocol avoids quantum tomography | Cyclobutadiene isomerization on superconducting quantum processor |

| Optimized Stacked Autoencoder (optSAE + HSAPSO) [7] | 95.52% classification accuracy | 0.010 seconds per sample; ± 0.003 stability | Handles large feature sets and diverse pharmaceutical data | DrugBank and Swiss-Prot datasets |

| AI-Driven Clinical Platforms (Exscientia) [8] | Multiple clinical candidates | ~70% faster design cycles; 10x fewer synthesized compounds | Closed-loop design-make-test-learn cycle with robotic automation | Phase I trials for OCD, oncology, and inflammation |

| Precision Medicine Molecular Diagnostics [9] [10] | Enables targeted therapies | High upfront testing cost but reduces overall treatment cost | Converts drugs from "experience goods" to "search goods" | EGFR mutation testing for gefitinib response |

| Quantum Hardware Techniques (IBM Eagle) [1] | Error reduction from 1-5% to 0.16% | 70,000 settings x 1,024 shots per setting | Blended scheduling mitigates time-dependent noise | BODIPY molecule energy estimation |

Detailed Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Hybrid Quantum-Neural Wavefunction (pUNN) Methodology

The pUNN framework combines quantum circuits with classical neural networks to compute molecular energies with reduced quantum hardware requirements [3].

Experimental Protocol:

- Wavefunction Initialization: Prepare the seniority-zero subspace using a paired Unitary Coupled-Cluster with double excitations (pUCCD) ansatz on N qubits.

- Hilbert Space Expansion: Add N ancilla qubits and apply an entanglement circuit (Ê) composed of N parallel CNOT gates to correlate original and ancilla qubits.

- Neural Network Processing: Apply a non-unitary operator represented by a classical neural network to modulate the quantum state.

- Perturbation Introduction: Apply single-qubit rotation gates (Ry) with small angles (0.2) to ancilla qubits to drive the state outside the seniority-zero subspace.

- Measurement and Energy Calculation: Use an efficient algorithm to compute expectation values without quantum state tomography.

Key Parameters:

- Neural network structure: L dense layers (L = N-3) with ReLU activation

- Hidden layer neurons: 2KN where K=2

- Particle number conservation enforced via mask function

Figure 1: pUNN Hybrid Quantum-Neural Workflow. This workflow demonstrates the integration of quantum circuits with classical neural networks for molecular energy calculation, optimizing for reduced quantum resource requirements [3].

Optimized Stacked Autoencoder with Hierarchical Optimization

The optSAE + HSAPSO framework addresses computational overhead in drug classification and target identification through deep learning and adaptive optimization [7].

Experimental Protocol:

- Data Preprocessing: Curate drug-target interaction data from DrugBank and Swiss-Prot repositories, normalizing molecular descriptors and protein features.

- Feature Extraction: Process input data through a stacked autoencoder (SAE) with multiple encoding layers to learn hierarchical representations.

- Hierarchical Optimization: Apply Hierarchically Self-Adaptive Particle Swarm Optimization (HSAPSO) to simultaneously tune SAE hyperparameters and architectural components.

- Classification: Feed the optimized features into a softmax classifier for druggable target prediction.

- Validation: Perform k-fold cross-validation and compare against SVM, XGBoost, and standard deep learning models.

Key Parameters:

- HSAPSO population size: 50 particles

- Inertia weight: adaptively decreased from 0.9 to 0.4

- Acceleration coefficients: c1 = c2 = 2.0

- Network architecture: 5 encoding layers with symmetrical decoding

Quantum Measurement Techniques for Molecular Energy Estimation

Precise measurement on quantum hardware requires specialized techniques to mitigate readout errors and reduce shot overhead [1].

Experimental Protocol:

- Locally Biased Random Measurements: Select measurement settings with greater impact on energy estimation to reduce shot requirements while maintaining informational completeness.

- Repeated Settings with Parallel QDT: Execute identical measurement configurations multiple times with parallel quantum detector tomography to characterize and mitigate readout errors.

- Blended Scheduling: Interleave circuits for different molecular states (S0, S1, T1) and quantum detector tomography to average out time-dependent noise.

- Error Mitigation: Use tomographically complete measurement data to construct unbiased estimators via classical post-processing.

Key Parameters:

- Number of measurement settings: 70,000

- Shots per setting: 1,024

- Execution: 10 repeated experiments on IBM Eagle r3 processor

- Target system: BODIPY molecule in active spaces from 8 to 28 qubits

Figure 2: Quantum Measurement Overhead Reduction. This workflow illustrates the integrated techniques for reducing measurement overhead in quantum computational chemistry, enabling high-precision energy estimation [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Overhead-Optimized Drug Discovery

| Tool/Platform | Function | Overhead Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| IBM Quantum Eagle Processors [1] | Quantum hardware for molecular energy estimation | Readout error ~10â»Â²; Mitigated via parallel quantum detector tomography |

| AI-Driven Design Platforms (Exscientia) [8] | Generative chemistry and automated precision design | Reduces synthesized compounds by 10x; ~70% faster design cycles |

| Stacked Autoencoder Architectures [7] | Feature extraction for drug-target classification | Computational complexity of 0.010s per sample; stable performance (±0.003) |

| Molecular Diagnostic Tests [9] [10] | Patient stratification for targeted therapies | Upfront testing cost offset by reduced overall treatment expenses |

| Hybrid Quantum-Classical Algorithms [3] | Molecular wavefunction representation | Shallow circuit depth (N qubits); noise-resilient through neural network component |

| Automated Digital Lab Systems [11] | Integrated data management and workflow orchestration | Reduces manual tasks and enables real-time data analysis for faster iterations |

| Bacoside A | Bacoside A | High-purity Bacoside A for research on neurodegeneration and type 2 diabetes. For Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. |

| Erythrinin C | Erythrinin C, MF:C20H18O6, MW:354.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Discussion: Overhead-Precision Trade-offs in Platform Selection

The comparative data reveals distinct overhead-precision profiles across platforms, necessitating careful selection based on research phase and resource constraints.

For Early-Stage Discovery: The optSAE + HSAPSO framework offers an optimal balance, delivering 95.52% accuracy with minimal computational overhead (0.010s per sample) for large-scale virtual screening [7]. Its stability (±0.003) makes it suitable for prioritizing candidates before resource-intensive experimental validation.

For Quantum-Accurate Simulations: Hybrid quantum-neural methods (pUNN) achieve near-chemical accuracy while maintaining feasible quantum resource requirements through their efficient measurement protocol [3]. This approach is particularly valuable for modeling complex molecular systems where classical methods become computationally prohibitive.

For Pipeline Integration: AI-driven platforms like Exscientia demonstrate that strategic overhead investment in automation and closed-loop systems can accelerate overall timelines despite high initial computational costs [8]. The 10x reduction in synthesized compounds represents significant savings in material and time resources.

For Clinical Translation: Precision medicine diagnostics introduce upfront testing overhead but ultimately reduce treatment costs by converting therapeutics from "experience goods" to "search goods" [10]. This paradigm shift improves success probability through patient stratification, potentially rescuing previously failed candidates [9].

The overarching trend across all platforms is the strategic allocation of overhead to bottlenecks with the highest impact on downstream success rates, whether through computational optimization, automation, or patient stratification.

This comparison demonstrates that effective overhead management is not merely about reduction but about strategic allocation to enhance both precision and scalability. Quantum techniques achieve remarkable precision gains through advanced error mitigation [1]; AI platforms dramatically compress design cycles through automation [8]; and classical machine learning balances both concerns for broad applicability [7]. The optimal platform selection depends critically on the specific research context—whether prioritizing speed, accuracy, or clinical translation—but the consistent theme across all approaches is that intelligent overhead optimization enables more efficient exploration of chemical space and biological complexity. As these technologies mature, their integration promises to further reduce barriers between hypothesis and therapeutic candidate, ultimately accelerating drug discovery through precision-guided efficiency.

Across the technologically advanced fields of semiconductors and pharmaceuticals, researchers face a common and critical challenge: the need to perform high-precision measurements on increasingly complex molecular systems. In the pharmaceutical industry, this translates to accurately estimating molecular energies to accelerate drug discovery, a task hampered by high research and development costs and regulatory hurdles [12]. In the semiconductor sector, similar precision is required for developing new materials and processes, all while navigating a global talent shortage and supply chain disruptions [13] [14]. Underpinning both fields is the pervasive issue of measurement overhead—the significant resource cost in terms of time, computational power, and specialized equipment required to obtain reliable data. This guide objectively compares the experimental performance of emerging strategies, particularly from the quantum computing domain, which offer promising pathways to reduce this overhead and redefine the limits of molecular research.

Comparative Analysis of Measurement Overhead Reduction Strategies

The following table summarizes the core performance characteristics of different computational approaches relevant to molecular simulation, based on recent experimental findings.

Table 1: Comparison of Molecular Simulation and Measurement Approaches

| Method / Strategy | Reported Precision/Error | Key Metric Improved | Experimental System/Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Practical Quantum Techniques (Locally biased, QDT, blended scheduling) | 0.16% (from a baseline of 1-5%) | Measurement error reduction [15] | BODIPY molecule energy estimation on IBM Eagle r3 quantum processor [15] |

| Hybrid Quantum-Neural Wavefunction (pUNN) | Near chemical accuracy | Accuracy & Noise resilience [3] | Isomerization of cyclobutadiene on a superconducting quantum computer [3] |

| Classical AI in Pharma R&D | Projected ~$1B savings in development costs over 5 years (Company-specific analysis) [16] | R&D Efficiency & Cost [16] | Clinical trial enrollment & drug development (Amgen, BMS, Sanofi) [16] |

| AI-Driven Job Shop Scheduling | Projected $12–25B in value by 2030; 10% reduction in operational costs [17] | Manufacturing Operational Cost [17] | Pharmaceutical production scheduling [17] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols for High-Precision Measurement

This section details the methodologies from key experiments cited in the comparison, providing a roadmap for researchers seeking to implement these advanced techniques.

Protocol 1: High-Precision Molecular Energy Estimation on Quantum Hardware

This protocol, derived from a 2025 study, outlines a suite of techniques to achieve chemical precision on near-term quantum devices for molecular energy estimation, specifically targeting the reduction of shot, circuit, and noise-related overheads [15].

1. System Preparation:

- Molecular System: The experiment focused on estimating the energy of the Boron-dipyrromethene (BODIPY) molecule. The methodology was tested on the Hartree-Fock state of this system across active spaces ranging from 8 to 28 qubits [15].

- Qubit State: The Hartree-Fock state was prepared on the quantum processor. This state is separable and requires no two-qubit gates, thereby isolating measurement errors from gate errors [15].

2. Measurement Strategy Execution:

- Informationally Complete (IC) Measurements: The team implemented IC measurements, which allow for the estimation of multiple observables from the same set of measurement data [15].

- Locally Biased Random Measurements: This technique was employed to reduce shot overhead. It intelligently selects measurement settings that have a larger impact on the final energy estimation, thus requiring fewer total measurements (shots) [15].

- Repeated Settings with Parallel Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT): To mitigate readout errors and reduce circuit overhead, the same measurement settings were repeated. Parallel QDT was used to characterize the noisy measurement detector and build an unbiased estimator for the molecular energy [15].

3. Noise Mitigation:

- Blended Scheduling: To combat time-dependent noise, a blended scheduling technique was used. This involved interleaving circuits for energy estimation with circuits for QDT, distributing them over time to average out temporal fluctuations in the quantum hardware [15].

4. Data Integration & Analysis:

- The data from the IC measurements and QDT were combined using classical post-processing. The tomographic model of the detector was used to correct the raw measurement outcomes, yielding a final, error-mitigated estimate of the molecular energy with drastically reduced error [15].

Experimental Workflow for Quantum Molecular Energy Estimation

Protocol 2: Hybrid Quantum-Neural Wavefunction (pUNN) for Molecular Energy

This protocol describes a hybrid quantum-machine learning framework designed for accurate and noise-resilient computation of molecular energies on quantum hardware [3].

1. Wavefunction Ansatz Construction:

- Quantum Circuit (pUCCD): A paired Unitary Coupled-Cluster with double excitations (pUCCD) circuit is used to learn the molecular wavefunction within the seniority-zero subspace. This component is responsible for capturing the quantum phase structure and is executed on the quantum computer [3].

- Neural Network Augmentation: A classical neural network is applied as a non-unitary post-processing operator. This network modulates the quantum state to correctly account for contributions from configurations outside the seniority-zero subspace, which the pUCCD circuit alone cannot capture. The network structure includes dense layers with ReLU activation functions and a final mask to enforce particle number conservation [3].

2. Efficient Expectation Value Measurement:

- The hybrid pUNN ansatz is specifically designed to allow for an efficient algorithm to compute the expectation value of the molecular Hamiltonian (energy) without resorting to full quantum state tomography, which is computationally prohibitive [3].

- The measurement protocol involves evaluating both the numerator 〈Ψ|Ĥ|Ψ〉 and the norm 〈Ψ|Ψ〉 by combining measurement outcomes from the quantum circuit with the output from the neural network [3].

3. Noise Resilience Validation:

- The method was experimentally validated on a superconducting quantum computer for the isomerization reaction of cyclobutadiene, a challenging multi-reference system. The results demonstrated that the pUNN approach maintained high accuracy despite the inherent noise of the quantum device, showcasing its practical utility for near-term quantum applications [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The following table catalogues key solutions and their functions as employed in the featured experiments and broader field of molecular systems research.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Advanced Molecular Measurement

| Item / Solution | Function in Research | Field of Application |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT) Kit | Characterizes the noisy measurement process of a quantum device, enabling the creation of an unbiased estimator to mitigate readout errors [15]. | Quantum Computational Chemistry |

| Informationally Complete (IC) Measurement Set | A pre-defined set of measurements that allows for the reconstruction of the quantum state and the estimation of multiple observables from the same data, reducing total measurement load [15]. | Quantum Computational Chemistry |

| Hybrid Quantum-Neural Wavefunction (pUNN) Model | A software framework combining a parameterized quantum circuit (pUCCD) with a classical neural network to represent complex molecular wavefunctions with high accuracy and noise resilience [3]. | Quantum Machine Learning / Chemistry |

| AI-Powered Scheduling & Simulation Suite | Optimizes complex production schedules and identifies "golden batch" parameters through digital twin technology, reducing operational costs and deviations [17]. | Pharmaceutical Manufacturing |

| Predictive Maintenance AI Algorithms | Analyzes sensor data (vibration, heat, current) to predict equipment failures before they occur, minimizing unplanned downtime in manufacturing and research [17]. | Semiconductor Fab, Pharma Manufacturing |

| Methylophiopogonanone B | Methylophiopogonanone B, CAS:74805-91-7, MF:C19H20O5, MW:328.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Demethyl calyciphylline A | Demethyl Calyciphylline A | Demethyl Calyciphylline A is a Daphniphyllum alkaloid for research use only (RUO). Explore its application in natural product and synthetic chemistry studies. |

The relentless pursuit of precision in molecular research is forging a convergent path between the semiconductor and pharmaceutical industries. Both sectors are increasingly reliant on a new class of tools—from error-mitigated quantum computations to AI-driven hybrid models—that share a common goal: to slash the overwhelming measurement and operational overhead that has traditionally constrained innovation. The experimental data demonstrates that these are not merely theoretical gains. Achieving a reduction in measurement errors by an order of magnitude, from 1-5% to 0.16%, on today's noisy quantum hardware is a tangible milestone [15]. Likewise, the projection of $1 billion in drug development savings through AI-powered clinical trials underscores the massive efficiency potential [16]. For researchers and drug development professionals, the imperative is clear: the strategic adoption and further development of these overhead-reduction protocols will be a critical determinant of success in accelerating the journey from scientific insight to real-world application.

In the field of quantum computational chemistry, achieving chemical precision—a measurement accuracy threshold of 1.6 × 10â»Â³ Hartree—is critical for obtaining chemically relevant results from molecular simulations [15] [1]. This level of precision is necessary because reaction rates are highly sensitive to changes in energy, and inaccuracies beyond this threshold render computational predictions unreliable for practical applications such as drug development and materials design. Reaching this goal on current noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices presents significant challenges due to inherent hardware limitations, particularly readout errors (the inaccurate determination of qubit states after measurement) and the formidable resource allocation requirements for precise measurements [15]. This guide examines and compares contemporary strategies for overcoming these obstacles, focusing on their experimental performance, methodological approaches, and practical implementation requirements.

The core challenge stems from the fundamental trade-offs between precision, resource requirements, and algorithmic efficiency. As molecular system size increases, the number of Pauli terms in the Hamiltonian grows as ð’ª(Nâ´), dramatically increasing the measurement burden [15]. Simultaneously, readout errors on the order of 10â»Â² further degrade measurement accuracy, making the 0.0016 Hartree target particularly elusive [1]. The following sections provide a detailed comparison of recently developed techniques that address these interconnected challenges through innovative measurement strategies, error mitigation protocols, and resource allocation optimizations.

Quantitative Comparison of Performance and Resource Metrics

The table below summarizes key performance indicators and resource requirements for several prominent techniques, enabling direct comparison of their effectiveness in addressing the challenges of chemical precision, readout errors, and resource allocation.

Table 1: Performance and Resource Comparison of Precision Enhancement Techniques

| Technique | Reported Error Reduction | Key Resources Optimized | System Scale Demonstrated (Qubits) | Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Practical Techniques for High-Precision Measurements [15] [1] | From 1-5% to 0.16% (order of magnitude) | Shot overhead, circuit overhead, temporal noise | 8-28 (BODIPY molecule) | IBM Eagle r3 quantum processor |

| Multireference Error Mitigation (MREM) [18] | Significant improvement over single-reference REM | Sampling overhead, circuit expressivity | Hâ‚‚O, Nâ‚‚, Fâ‚‚ molecules | Comprehensive simulations |

| AIM-ADAPT-VQE [2] | Enables measurement-free gradient estimation | Measurement overhead for gradient evaluations | Hâ‚‚, 1,3,5,7-octatetraene | Numerical simulations |

| Hybrid Quantum-Neural Wavefunction (pUNN) [3] | Achieves near-chemical accuracy | Qubit count (N qubits), circuit depth | Nâ‚‚, CHâ‚„, cyclobutadiene | Superconducting quantum computer |

| Separate State Prep & Measurement Error Mitigation [19] | Fidelity improvement by an order of magnitude | Quantification resources, mitigation complexity | Cloud experiments on IBM superconducting processors | IBM quantum computers |

The data reveals distinct strategic approaches to the precision challenge. The "Practical Techniques" achieve remarkable error reduction through a multi-pronged approach targeting different noise sources and overheads [15] [1], while MREM focuses specifically on extending error mitigation to strongly correlated systems where single-reference methods fail [18]. AIM-ADAPT-VQE addresses the specific measurement overhead of adaptive algorithms [2], and the pUNN approach leverages hybrid quantum-classical representations to maintain accuracy with reduced quantum resources [3].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Practical High-Precision Measurement Techniques

This methodology employs an integrated approach to address multiple sources of error and overhead simultaneously [15] [1]:

Locally Biased Random Measurements: This technique reduces shot overhead (the number of quantum measurements required) by prioritizing measurement settings that have greater impact on energy estimation, while maintaining the informationally complete nature of the measurement strategy.

Repeated Settings with Parallel Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT): This approach reduces circuit overhead (the number of distinct circuit configurations needed) and mitigates readout errors by characterizing quantum measurement imperfections through detector tomography.

Blended Scheduling: This method addresses time-dependent noise by interleaving different circuit types during execution, ensuring temporal noise fluctuations affect all measurements uniformly.

Experimental Workflow for High-Precision Molecular Energy Estimation

This methodology was validated through molecular energy estimation of the BODIPY molecule across active spaces ranging from 8 to 28 qubits, demonstrating consistent error reduction to 0.16% despite readout errors on the order of 10â»Â² [15] [1].

Multireference Error Mitigation (MREM)

MREM addresses a key limitation of single-reference error mitigation (REM) in strongly correlated systems [18]:

Reference State Construction: Instead of using a single Hartree-Fock determinant, MREM employs compact multireference states composed of dominant Slater determinants identified through inexpensive classical methods.

Givens Rotation Circuits: These circuits efficiently prepare multireference states on quantum hardware while preserving physical symmetries (particle number, spin projection) and maintaining controlled expressivity.

Error Mitigation Protocol: The exact energy of the multireference state is computed classically, then compared to its noisy quantum measurement to characterize and remove systematic errors.

The experimental implementation demonstrated significant improvement over single-reference REM for challenging systems like stretched Fâ‚‚ molecules, where strong electron correlation makes single-determinant references inadequate [18].

Hybrid Quantum-Neural Wavefunctions (pUNN)

The pUNN approach creates a hybrid representation that leverages the complementary strengths of quantum circuits and neural networks [3]:

Quantum Component: A linear-depth paired Unitary Coupled-Cluster with double excitations (pUCCD) circuit captures quantum phase structure in the seniority-zero subspace.

Neural Network Component: A classical neural network accounts for contributions from unpaired configurations outside the seniority-zero subspace.

Efficient Measurement Protocol: A specialized algorithm computes physical observables without quantum state tomography or exponential measurement overhead by leveraging the specific structure of the hybrid representation.

This approach maintains the low qubit count (N qubits) and shallow circuit depth of pUCCD while achieving accuracy comparable to more resource-intensive methods like UCCSD and CCSD(T) [3].

Table 2: Key Experimental Resources for Precision Quantum Chemistry

| Resource Category | Specific Solution/Technique | Primary Function | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Measurement Strategies | Informationally Complete (IC) Measurements [15] [2] | Enable estimation of multiple observables from same data | Reduces total measurement burden |

| Locally Biased Random Measurements [15] [1] | Prioritizes informative measurement bases | Reduces shot overhead | |

| Error Mitigation | Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT) [15] [1] | Characterizes and corrects readout errors | Requires additional calibration circuits |

| Multireference Error Mitigation (MREM) [18] | Extends error mitigation to strongly correlated systems | Needs classical multireference calculation | |

| Separate State Prep & Measurement Mitigation [19] | Independently addresses different error sources | Linear complexity with qubit count | |

| Algorithmic Frameworks | ADAPT-VQE with IC Measurements [2] | Reduces measurement overhead in adaptive algorithms | Enables commutator estimation without extra measurements |

| Hybrid Quantum-Neural Wavefunctions [3] | Combines quantum circuits with neural networks | Maintains accuracy with reduced quantum resources | |

| Hardware Strategies | Blended Scheduling [15] | Mitigates time-dependent noise | Interleaves circuit types during execution |

Cross-Technique Analysis and Implementation Pathways

The relationship between different precision enhancement techniques reveals complementary approaches that can be strategically combined based on specific research requirements and available resources.

Strategic Pathways for Measurement Overhead Reduction

Strategic Implementation Guidelines

For Strongly Correlated Systems: The MREM framework provides a crucial extension to standard error mitigation by incorporating multireference states, which is essential for studying bond dissociation, transition metals, and other systems where single-reference methods fail [18].

For Measurement-Intensive Algorithms: AIM-ADAPT-VQE with informationally complete measurements significantly reduces the measurement overhead associated with gradient estimation, a major bottleneck in adaptive algorithms [2].

For Readout Error Dominated Regimes: The integrated practical techniques approach (locally biased measurements, QDT, blended scheduling) provides comprehensive protection against the multiple error sources that collectively impede precision [15] [1].

For Resource-Constrained Environments: Hybrid quantum-neural approaches like pUNN maintain accuracy while reducing quantum resource requirements, making them suitable for current NISQ devices with limited qubit counts and coherence times [3].

The convergence of these techniques points toward a future where robust quantum computational chemistry requires co-design of algorithmic strategies, error mitigation protocols, and hardware-specific implementations. Each method provides distinct advantages for specific molecular systems and experimental conditions, enabling researchers to select and combine approaches based on their particular precision challenges and resource constraints.

Advanced Techniques for Overhead Reduction: Quantum and Classical Approaches

Adaptive Informationally Complete (IC) Measurements for Efficient Data Reuse

In the field of quantum computational chemistry, accurately estimating molecular properties like ground state energy is fundamental to advancing drug discovery and materials science. However, near-term quantum devices face significant constraints, with measurement overhead representing a critical bottleneck. Quantum computers suffer from high readout errors, limited sampling statistics, and circuit execution constraints that make high-precision measurements particularly challenging [1].

Adaptive Informationally Complete (IC) measurements have emerged as a powerful framework for addressing these limitations. IC measurements allow researchers to reconstruct the full quantum state of a system, enabling the estimation of multiple observables from the same set of measurement data [1]. This data reuse capability is especially valuable for measurement-intensive algorithms that would otherwise require prohibitive numbers of separate measurements. The adaptive component further enhances efficiency by dynamically optimizing measurement strategies based on intermediate results, focusing resources where they provide the most information gain.

This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of adaptive IC measurement implementations, focusing on their performance in reducing measurement overhead while maintaining the chemical precision (1.6 × 10−3 Hartree) required for predictive molecular simulations [1].

Core Methodologies and Comparative Analysis

Fundamental Principles of Adaptive IC Measurements

Informationally Complete (IC) measurements are defined by their ability to fully characterize a quantum state through a set of measurement operators that form a basis for the space of quantum observables. The adaptive component introduces a feedback loop where measurement strategies are dynamically optimized based on accumulated data.

The key advantage of this approach lies in its data reuse capability. Once an IC measurement is performed, the collected data can be processed to estimate any observable of interest without returning to the quantum device [1]. This is particularly beneficial for complex algorithms like ADAPT-VQE, qEOM, and SC-NEVPT2 that require numerous expectation value estimations [1].

Adaptive IC implementations typically incorporate quantum detector tomography (QDT) to characterize and mitigate readout errors [1]. By modeling the noisy measurement process, researchers can construct unbiased estimators that significantly improve measurement accuracy, as demonstrated by error reductions from 1-5% to 0.16% in molecular energy estimation [1].

Technical Implementation Comparison

Three prominent implementations of adaptive IC measurements demonstrate different approaches to overhead reduction:

Table 1: Comparison of Adaptive IC Measurement Methodologies

| Method | Core Approach | Key Innovation | Computation Balance |

|---|---|---|---|

| AIM-ADAPT-VQE [2] | Adaptive Informationally Complete Generalized Measurements | Reuses IC measurement data to estimate all commutators in ADAPT-VQE via classical post-processing | Quantum: Single IC measurement per stepClassical: Post-processing for all gradient estimations |

| Locally Biased IC Measurements [1] | Hamiltonian-Informed Sampling Biases | Prioritizes measurement settings with greater impact on specific observables (e.g., energy) | Quantum: Reduced shots for same precisionClassical: Bias calculation and data reweighting |

| BAI with Successive Elimination [20] | Best-Arm Identification for Generator Selection | Adaptively allocates measurements, discarding unpromising candidates early | Quantum: Progressive focus on best candidatesClassical: Elimination decision logic |

AIM-ADAPT-VQE specifically addresses the gradient estimation bottleneck in adaptive variational algorithms. By exploiting informationally complete positive operator-valued measures (POVMs), it enables the estimation of all commutator operators in the ADAPT-VQE pool using only classically efficient postprocessing once the energy measurement data is collected [2]. This approach can potentially eliminate the measurement overhead for gradient evaluations entirely for some systems [2].

Locally Biased Random Measurements reduce shot overhead by incorporating prior knowledge about the Hamiltonian structure. Instead of uniform sampling of measurement settings, this method biases the selection toward settings that have a bigger impact on the energy estimation while maintaining the informationally complete nature of the measurement strategy [1]. This preserves the ability to estimate multiple observables while improving statistical efficiency for the target observable.

The Best-Arm Identification with Successive Elimination approach reformulates generator selection in adaptive algorithms as a multi-armed bandit problem. The Successive Elimination algorithm allocates measurements across rounds and progressively discards candidates with small gradients, concentrating sampling effort on promising generators [20]. This avoids the uniform precision requirement of conventional methods that waste resources on characterizing unpromising candidates.

Performance Analysis and Experimental Data

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Experimental implementations of adaptive IC measurements demonstrate significant improvements in both precision and efficiency across various molecular systems:

Table 2: Experimental Performance of Adaptive IC Measurement Techniques

| Method | Test System | Performance Gains | Precision Achieved | Resource Reduction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AIM-ADAPT-VQE [2] | Hâ‚‚, Hâ‚„, 1,3,5,7-octatetraene Hamiltonians | Eliminated gradient measurement overhead | High accuracy convergence | CNOT count close to ideal with chemical precision measurements |

| QDT with IC Measurements [1] | BODIPY molecule (4e4o to 14e14o active spaces) | Reduced estimation bias, mitigated readout errors | ~0.16% absolute error (near chemical precision) | Order of magnitude error reduction from 1-5% baseline |

| Successive Elimination [20] | Molecular systems with large operator pools | Substantial reduction in measurements while preserving accuracy | Maintained ground-state energy accuracy | Focused measurements on promising candidates only |

The BODIPY molecule case study provides particularly compelling evidence for the effectiveness of adaptive IC measurements. Researchers achieved a reduction in measurement errors by an order of magnitude, from initial errors of 1-5% down to 0.16%, approaching the target of chemical precision at 1.6 × 10−3 Hartree [1]. This precision was maintained across increasingly large active spaces from 4e4o (8 qubits) to 14e14o (28 qubits), demonstrating scalability [1].

For AIM-ADAPT-VQE, numerical simulations indicated that the measurement data obtained to evaluate the energy could be reused to implement ADAPT-VQE with no additional measurement overhead for the systems considered [2]. When the energy was measured within chemical precision, the CNOT count in the resulting circuits was close to the ideal one, indicating minimal compromise in circuit architecture despite significantly reduced measurements [2].

Workflow and System Architecture

The following diagram illustrates the generalized workflow for adaptive IC measurement protocols, synthesizing common elements across the different implementations:

Diagram 1: Adaptive IC Measurement Workflow. This flowchart illustrates the iterative process of adaptive IC measurements, showing the closed-loop feedback between classical processing and quantum execution that enables efficient data reuse.

Research Toolkit: Essential Methods and Materials

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Protocol 1: Quantum Detector Tomography with IC Measurements

- Device Calibration: Perform informationally complete measurements on prepared basis states to characterize the noisy measurement process [1].

- Model Construction: Build a linear model of the measurement apparatus using the collected calibration data [1].

- Mitigation Matrix: Compute the pseudoinverse of the measurement matrix to enable unbiased estimation of quantum observables [1].

- Experimental Execution: Perform IC measurements on the target quantum state using the characterized apparatus.

- Data Processing: Apply the mitigation matrix to raw measurement outcomes to obtain error-mitigated estimates of expectation values [1].

Protocol 2: AIM-ADAPT-VQE Implementation

- Initialization: Prepare the reference state (typically Hartree-Fock) on the quantum processor [2].

- Energy Evaluation: Perform adaptive informationally complete generalized measurements to evaluate the current energy [2].

- Gradient Estimation: Reuse the IC measurement data to estimate all commutators of operators in the ADAPT-VQE pool through classical post-processing [2].

- Generator Selection: Identify the operator with the largest gradient magnitude to append to the ansatz [2] [20].

- Parameter Optimization: Variationally optimize the parameters of the expanded ansatz.

- Iteration: Repeat steps 2-5 until convergence criteria are met [2].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Adaptive IC Experiments

| Resource Category | Specific Solution | Function/Purpose | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Measurement Protocols | Informationally Complete POVMs | Enable full state characterization and multi-observable estimation from single dataset | Dilation POVMs [2], Locally biased IC measurements [1] |

| Error Mitigation | Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT) | Characterizes and corrects readout errors using calibration data | Parallel QDT execution alongside main experiment [1] |

| Sampling Strategies | Locally Biased Random Measurements | Reduces shot overhead by prioritizing informative measurement settings | Hamiltonian-inspired biasing for molecular energy estimation [1] |

| Adaptive Algorithms | Successive Elimination | Minimizes measurements by progressively focusing on promising candidates | Best-Arm Identification for generator selection [20] |

| Classical Processing | Blended Scheduling | Mitigates time-dependent noise by interleaving different circuit types | Temporal mixing of Hamiltonian-circuit pairs and QDT circuits [1] |

| 16-Oxoprometaphanine | 16-Oxoprometaphanine, MF:C20H23NO6, MW:373.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Erythrinin D | Erythrinin D, MF:C21H18O6, MW:366.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Adaptive Informationally Complete measurements represent a significant advancement in measurement efficiency for quantum computational chemistry. The methodologies compared in this guide demonstrate that strategic data reuse through adaptive IC frameworks can reduce measurement overhead by orders of magnitude while maintaining the precision required for predictive molecular simulations.

The most effective implementations combine multiple strategies: IC measurements for maximal information extraction, adaptive techniques for resource allocation, and error mitigation for result fidelity. As quantum hardware continues to evolve, these measurement strategies will play an increasingly crucial role in enabling the simulation of pharmacologically relevant molecules and accelerating drug discovery pipelines.

Future research directions include developing more sophisticated adaptive heuristics, optimizing IC measurements for specific observable classes, and creating hardware-tailored implementations that account for device-specific noise characteristics. The integration of these advanced measurement strategies with evolving quantum algorithms promises to further extend the boundaries of what is computationally feasible on near-term quantum devices.

Best-Arm Identification (BAI) and Successive Elimination for Optimal Generator Selection

In the pursuit of simulating molecular systems on near-term quantum devices, variational quantum algorithms (VQAs) have emerged as a leading strategy. Among these, adaptive variational algorithms dynamically construct ansätze by iteratively selecting and appending parametrized unitaries from an operator pool. A critical bottleneck in this process is the prohibitively high measurement cost required for generator selection, where energy gradients must be estimated for a large operator pool. This scaling bottleneck can reach up to ð’ª(Nâ¸) with the number of spin-orbitals, severely limiting applications to chemically relevant molecular systems [20].

This comparative analysis examines how Best-Arm Identification (BAI) frameworks, particularly the Successive Elimination algorithm, address this challenge by reformulating generator selection as a pure-exploration bandit problem. By adaptively allocating measurements and discarding unpromising candidates early, this approach substantially reduces measurement overhead while preserving ground-state energy accuracy, making adaptive variational algorithms more practical for near-term quantum simulations [20].

Theoretical Foundations: From Bandit Problems to Quantum Measurement

Best-Arm Identification in Stochastic Multi-Armed Bandits

The Best-Arm Identification problem originates from stochastic multi-armed bandit frameworks, where a learner sequentially queries different "arms" to identify the one with the largest expected reward using as few samples as possible. In the fixed-confidence setting, algorithms aim to guarantee correct identification with probability ≥ 1-δ while minimizing sample complexity [21].

Formally, for K arms with unknown reward distributions νâ‚, ..., νK with means μâ‚, ..., μK, the goal is to identify the arm with the largest mean, a* = argmaxáµ¢ μᵢ, with high confidence. This pure-exploration formulation differs from cumulative regret minimization and presents unique challenges in optimal resource allocation [21].

Multi-Fidelity Extensions

Recent extensions to BAI include multi-fidelity approaches, where querying the original arm is expensive, but multiple biased approximations are available at lower costs. This setting mirrors quantum computational environments where precise measurements are costly, but various approximations can inform selection strategies [22].

Methodological Approaches: Algorithmic Solutions for Generator Selection

Successive Elimination for Adaptive VQEs

The Successive Elimination algorithm adapts the BAI framework to generator selection in adaptive variational algorithms by mapping each generator to an arm whose "reward" is the energy gradient magnitude |gᵢ| = |⟨ψₖ|[Ĥ,Ĝᵢ]|ψₖ⟩|. The algorithm proceeds through multiple rounds, progressively eliminating candidates with small gradients while concentrating sampling effort on promising generators [20].

The SE algorithm implements the following workflow:

- Initialization: Begin with the quantum state |ψₖ⟩ obtained from the last VQE optimization

- Adaptive Measurements: For each generator in the active set, estimate energy gradients with precision εᵣ = cᵣ·ε

- Gradient Estimation: Compute |gáµ¢| by summing estimated expectation values of measurable fragments

- Candidate Elimination: Eliminate generators satisfying |gáµ¢| + Ráµ£ < M - Ráµ£, where M is the current maximum gradient

- Termination: Continue until one candidate remains or maximum rounds reached [20]

Alternative Measurement Reduction Strategies

Other approaches to reducing measurement overhead include:

- Pool Reduction: Using qubit-based operator pools of size 2N-2 or exploiting molecular symmetries to construct compact pools [20]

- RDM Reformulation: Expressing gradients via reduced density matrices without requiring more than three-body RDMs [20]

- Operator Bundling: Grouping qubit-based operators to reduce gradient evaluation scaling from ð’ª(Nâ¸) to ð’ª(Nâµ) [20]

- Information Recycling: Reusing measurement data from VQE subroutines in subsequent gradient evaluations [20]

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Measurement Reduction Strategies

| Strategy | Key Mechanism | Scaling Improvement | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Successive Elimination (BAI) | Adaptive allocation via early candidate elimination | Focuses resources on promising candidates | Requires multiple measurement rounds |

| Pool Reduction | Smaller operator pools (2N-2) | Reduces number of gradients to evaluate | Increased risk of local minima trapping |

| RDM Reformulation | Express gradients via reduced density matrices | ð’ª(Nâ¸) to ð’ª(Nâ´) | Approximation of higher-body RDMs |

| Operator Bundling | Group commuting operators | ð’ª(Nâ¸) to ð’ª(Nâµ) | Increased circuit complexity for diagonalization |

| Information Recycling | Reuse previous measurement data | Reduces redundant measurements | Limited by correlation between iterations |

Experimental Protocols and Performance Comparison

Experimental Design for BAI Assessment

To evaluate the performance of Successive Elimination for generator selection, researchers employ numerical experiments on molecular systems with the following protocol:

- System Preparation: Initialize with Hartree-Fock reference state |ψ₀⟩

- Ansatz Construction: Build wavefunction as |ψₖ⟩ = âˆáµ¢â‚Œâ‚áµ e^θâ±á´³â± |ψ₀⟩

- Gradient Estimation: Decompose commutators [Ĥ,Ĝᵢ] into measurable fragments using qubit-wise commuting (QWC) fragmentation with sorted insertion (SI) grouping [20]

- Adaptive Sampling: Implement SE algorithm with multiple rounds of precision refinement

- Performance Metrics: Track both measurement cost reduction and ground-state energy accuracy

Comparative Performance Data

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison of Measurement Reduction Techniques

| Method | Measurement Reduction | Accuracy Preservation | Implementation Complexity | System Size Scalability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Successive Elimination | Substantial reduction demonstrated | Preserves ground-state accuracy | Moderate (adaptive allocation) | Excellent for large systems |

| QWC/SI Grouping | 1.5 to 7-fold reduction for vibrational systems [23] | Maintains chemical accuracy | Low (classical preprocessing) | Good for medium systems |

| Informationally Complete Measurements | Enables multiple observable estimation [1] | Achieves 0.16% error vs 1-5% baseline [1] | High (requires detector tomography) | Limited by circuit overhead |

| Coordinate Transformations | 3-fold average reduction (up to 7-fold) [23] | Preserves anharmonic state accuracy | Medium (coordinate optimization) | System-dependent |

Case Study: High-Precision Measurement for Molecular Systems

Recent work on the BODIPY molecule demonstrates practical techniques for high-precision measurements on near-term quantum hardware. By implementing locally biased random measurements, repeated settings with parallel quantum detector tomography, and blended scheduling for time-dependent noise mitigation, researchers reduced measurement errors by an order of magnitude from 1-5% to 0.16% [1].

This approach employed informationally complete (IC) measurements, allowing estimation of multiple observables from the same measurement data—particularly valuable for measurement-intensive algorithms like ADAPT-VQE. The BODIPY case study examined active spaces ranging from 4e4o (8 qubits) to 14e14o (28 qubits), demonstrating scalability of precision enhancement techniques [1].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Resource | Function | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Qubit-Wise Commuting Fragmentation | Decomposes commutators into measurable fragments | Sorted Insertion grouping reduces measurements [20] |

| Quantum Detector Tomography | Mitigates readout errors via calibration | Enables unbiased estimation; reduces errors to 0.16% [1] |

| Locally Biased Random Measurements | Reduces shot overhead via targeted sampling | Prioritizes measurement settings with bigger impact on energy estimation [1] |

| Blended Scheduling | Mitigates time-dependent noise | Interleaves circuits to equalize temporal fluctuations [1] |

| Vibrational Coordinate Optimization | Reduces Hamiltonian measurement variance | HOLCs provide 3-7 fold reduction in measurements [23] |

| Multi-Fidelity Bandit Algorithms | Leverages approximations for cost reduction | IISE algorithm reduces total cost using biased approximations [22] |

Workflow and System Architecture

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow for Successive Elimination in adaptive variational algorithms:

Best-Arm Identification for Generator Selection Workflow

The algorithm proceeds through multiple rounds of adaptive measurement and candidate elimination. In each round r:

- The active generator set Aáµ£ ⊆ 𒜠begins with all candidates (Aâ‚€ = ð’œ)

- Each generator's gradient is estimated with precision εᵣ = cᵣ·ε (cᵣ ≥ 1)

- The maximum gradient M in Aáµ£ is identified

- Generators satisfying |gᵢ| + Rᵣ < M - Rᵣ are eliminated (Rᵣ = dᵣ·εᵣ)

- The process continues until one candidate remains or maximum rounds reached

- In the final round (r = L), c_L = 1 for target accuracy ε [20]

The reformulation of generator selection in adaptive variational algorithms as a Best-Arm Identification problem represents a significant advancement in measurement overhead reduction for quantum computational chemistry. The Successive Elimination algorithm addresses the fundamental limitation of existing methods that require estimating all pool gradients to fixed precision, instead adaptively allocating measurements and discarding unpromising candidates early.

When integrated with complementary strategies like qubit-wise commuting fragmentation, coordinate transformations, and informationally complete measurements, BAI frameworks enable substantial measurement cost reductions while preserving the accuracy essential for molecular energy estimation. This multi-faceted approach to measurement optimization makes practical quantum simulation of chemically relevant molecular systems increasingly feasible on near-term quantum devices.

As quantum hardware continues to advance, these algorithmic innovations in resource allocation will play a crucial role in bridging the gap between theoretical promise and practical utility in quantum computational chemistry, potentially accelerating discoveries in drug development and materials science.

Locally Biased Random Measurements and Shot Reduction Strategies

Accurately measuring quantum observables, particularly molecular Hamiltonians, is a fundamental yet resource-intensive task in quantum computational chemistry. On near-term quantum devices, high readout errors and finite sampling constraints make achieving chemical precision a significant challenge [24]. The high "shot overhead" – the vast number of repeated circuit executions needed for precise expectation value estimation – is a critical bottleneck for practical applications like drug development [25]. This guide compares leading strategies designed to reduce this measurement overhead, focusing on the performance of Locally Biased Classical Shadows (LBCS), Classical Shadows with Derandomization, Decision Diagrams, and Adaptive Informationally Complete (AIC) Measurements. We objectively evaluate their experimental performance, resource requirements, and practical implementation to inform researchers' selection of appropriate measurement strategies.

Comparative Performance Analysis of Measurement Strategies

The table below summarizes the key performance characteristics of the four primary measurement overhead reduction strategies, based on recent research findings.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Shot Reduction Strategies

| Strategy | Key Mechanism | Reported Performance Gains | Circuit Depth Overhead | Classical Computational Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Locally Biased Classical Shadows (LBCS) [24] [25] | Biases random Pauli measurements using a classical reference state. | >57% reduction in measurements vs. unbiased shadows [26]; Order of magnitude error reduction (to 0.16%) in molecular energy estimation [24]. | None [25] | Moderate (optimization of local biases) |

| Classical Shadows with Derandomization [26] | Derandomizes measurement basis selection to cover all Pauli terms in fewer rounds. | -- | None | High [26] |

| Decision Diagrams [26] | Efficient data structure for grouping and derandomizing measurements. | >80% reduction in measurements vs. classical shadows [26]. | None | Lower than derandomization [26] |

| Adaptive IC Measurements (AIM) [2] | Uses informationally complete POVMs; data can be reused for multiple operators. | Eliminates measurement overhead for gradient evaluations in ADAPT-VQE for some systems [2]. | Increased (for POVM implementation) | Low (for classical post-processing) |

Detailed Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for Locally Biased Classical Shadows (LBCS)

The LBCS protocol enhances the standard classical shadows approach by incorporating prior knowledge to minimize variance [25].

Input Preparation:

- Target Hamiltonian: ( H = \sumQ \alphaQ Q ), where ( Q ) are Pauli operators.

- Reference State: A classically efficient approximation of the quantum state ( \rho ), such as a Hartree-Fock state or a multi-reference perturbation theory state [25].

- Quantum State Preparation: Prepare the target state ( \rho ) on the quantum processor.

Bias Optimization: