The Born-Oppenheimer Approximation: A Foundational Pillar for Quantum Chemistry and Modern Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the Born-Oppenheimer (BO) approximation, the cornerstone of quantum chemistry that enables the computational treatment of molecular systems by separating electronic and nuclear motions.

The Born-Oppenheimer Approximation: A Foundational Pillar for Quantum Chemistry and Modern Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the Born-Oppenheimer (BO) approximation, the cornerstone of quantum chemistry that enables the computational treatment of molecular systems by separating electronic and nuclear motions. We begin by establishing its foundational physical principles and historical context. The discussion then progresses to its critical methodological role in computational chemistry, illustrating how it facilitates the calculation of molecular structure, properties, and reaction pathways. A dedicated section addresses the approximation's known limitations—such as breakdowns in photochemistry and near conical intersections—and surveys advanced troubleshooting methods and computational frameworks like non-adiabatic molecular dynamics that move beyond the BO paradigm. Finally, we validate the approximation's enduring utility through comparative analysis with emerging 'chemistry without BO' approaches, highlighting its irreplaceable role and future potential in accelerating biomedical research and drug development.

The Bedrock of Quantum Chemistry: Unpacking the Born-Oppenheimer Approximation

In the burgeoning field of quantum mechanics in 1927, a seminal collaboration between Max Born and his 23-year-old graduate student, J. Robert Oppenheimer, yielded an approximation that would become one of the most indispensable tools in quantum chemistry and molecular physics [1] [2]. The Born-Oppenheimer (BO) approximation, as it became known, addressed a central problem in the quantum description of molecules: the formidable complexity of solving the Schrödinger equation for a system comprising both fast-moving electrons and much heavier, slow-moving atomic nuclei [3]. Their work, published in the paper "On the Quantum Theory of Molecules," provided a practical method to separate this complex problem into more manageable parts [2]. While the approximation bears both names, historical accounts recognize that the theory is predominantly Oppenheimer's work [2]. This article explores the historical context, fundamental principles, and enduring legacy of this approximation, which continues to underpin modern computational studies in molecular systems research, including drug development.

Historical and Scientific Context

The Intellectual Climate of 1927

The year 1927 was a pivotal moment for quantum physics. It was the year of the Fifth Solvay International Conference in Brussels, a gathering of 29 of the world's most brilliant physicists, including 17 who were or would become Nobel laureates [4] [5]. The conference theme, "Electrons and Photons," centered on the intense debates surrounding the newly formulated quantum theory. Attendees included Albert Einstein, Niels Bohr, Werner Heisenberg, Erwin Schrödinger, and Paul Dirac [4]. It was within this ferment of new ideas—wave-particle duality, matrix mechanics, and the uncertainty principle—that Born and Oppenheimer developed their approximation.

Max Born, a German-British physicist and one of the founders of quantum mechanics, is best known for his probabilistic interpretation of the wave function [4]. J. Robert Oppenheimer, who would later become known as the "father of the atomic bomb," was at the time a young and promising doctoral student [6] [2]. The collaboration between an established figure and a precocious graduate student produced a theory that would fundamentally shape how scientists visualize and compute molecular properties.

The Core Problem in Molecular Quantum Mechanics

The fundamental challenge that Born and Oppenheimer sought to address was the intractable nature of the molecular Schrödinger equation. A molecule's total energy and wave function are described by solving this equation, which must account for the coordinates of every single particle—electrons and nuclei [1].

To illustrate the scale of this problem, consider the benzene molecule (C₆H₆), which consists of 12 nuclei and 42 electrons [3] [1]. The complete molecular Schrödinger equation for benzene is a partial differential eigenvalue equation in:

- 3 × 12 = 36 nuclear coordinates, and

- 3 × 42 = 126 electronic coordinates,

- resulting in a total of 162 variables [3] [1].

The computational complexity of solving an eigenvalue equation increases faster than the square of the number of coordinates. A naive approach would require solving an equation with a complexity on the order of (162^2 = 26,244) [1]. This was, and remains, a prohibitively difficult task for exact solution. The Born-Oppenheimer approximation provided the key to breaking this deadlock.

Table 1: The Computational Complexity of the Molecular Schrödinger Equation

| Molecule | Particles | Number of Variables | Complexity (order of n²) |

|---|---|---|---|

| H₂⺠(Simplest molecule) | 2 nuclei, 1 electron [2] | 9 | 81 |

| Benzene (C₆H₆) | 12 nuclei, 42 electrons [3] [1] | 162 | 26,244 |

| Benzene (with BO approximation) | Electronic Equation (per geometry) | 126 | 15,876 |

| Nuclear Equation | 36 | 1,296 |

The Physical Basis and Mathematical Formulation

The Physical Insight: Mass Disparity and Time Scales

The physical foundation of the BO approximation rests on the significant mass disparity between atomic nuclei and electrons [7] [8]. The lightest nucleus, the proton in hydrogen, is approximately 1836 times heavier than an electron [3]. This mass difference has a direct consequence on the dynamics of these particles.

Due to their opposite charges, electrons and nuclei exert mutual attractive Coulomb forces on each other. The acceleration a particle experiences is inversely proportional to its mass ((a = F/m)) [7] [8]. Consequently, electrons accelerate and move much more rapidly than nuclei. As a result, the electrons effectively instantaneously adjust their positions and momenta whenever the nuclei move [2]. This allows one to envision that from the perspective of the electrons, the massive nuclei appear almost stationary [8]. This insight is the cornerstone of the approximation.

The Two-Step Mathematical Procedure

The BO approximation simplifies the molecular Hamiltonian, which describes the total energy of the system. The full Hamiltonian includes the kinetic energy of the nuclei, the kinetic energy of the electrons, and all the potential energy terms from Coulomb interactions (electron-electron repulsion, nucleus-nucleus repulsion, and electron-nucleus attraction) [3] [1].

The approximation proceeds in two consecutive steps:

Step 1: The Clamped Nuclei Electronic Calculation In this first step, the nuclear kinetic energy is omitted from the total Hamiltonian [3] [1]. The nuclei are treated as stationary, fixed at a particular configuration in space, R. The remaining electronic Hamiltonian, (H\text{elec}(\mathbf{r}; \mathbf{R})), still includes the electron-nucleus attractions, with the nuclear positions R entering as fixed parameters (not variables). One then solves the electronic Schrödinger equation for this fixed nuclear geometry: [ H\text{elec}(\mathbf{r}; \mathbf{R}) \chik(\mathbf{r}; \mathbf{R}) = E{k}(\mathbf{R}) \chik(\mathbf{r}; \mathbf{R}) ] Here, (\chik(\mathbf{r}; \mathbf{R})) is the electronic wavefunction for the (k)-th electronic state (e.g., the ground state), and (E_{k}(\mathbf{R})) is the corresponding electronic energy, which depends parametrically on the nuclear coordinates R [3] [1]. This electronic energy includes contributions from electron kinetic energies, interelectronic repulsions, and electron-nuclear attractions [3].

This calculation is repeated for many different nuclear configurations. The set of electronic energies (E_{k}(\mathbf{R})) obtained defines the Potential Energy Surface (PES) for the nuclei [3].

Step 2: The Nuclear Schrödinger Equation In the second step, the nuclear kinetic energy is reintroduced. The electronic energy (E{k}(\mathbf{R})), which includes nuclear repulsion, now serves as the effective potential energy for the nuclear motion. The Schrödinger equation for the nuclei is solved: [ [T\text{nuc} + E{k}(\mathbf{R})] \phi(\mathbf{R}) = E \phi(\mathbf{R}) ] where (T\text{nuc}) is the nuclear kinetic energy operator, and (E) is the total molecular energy [3] [1]. The solution to this equation provides the vibrational, rotational, and translational energy levels of the molecule.

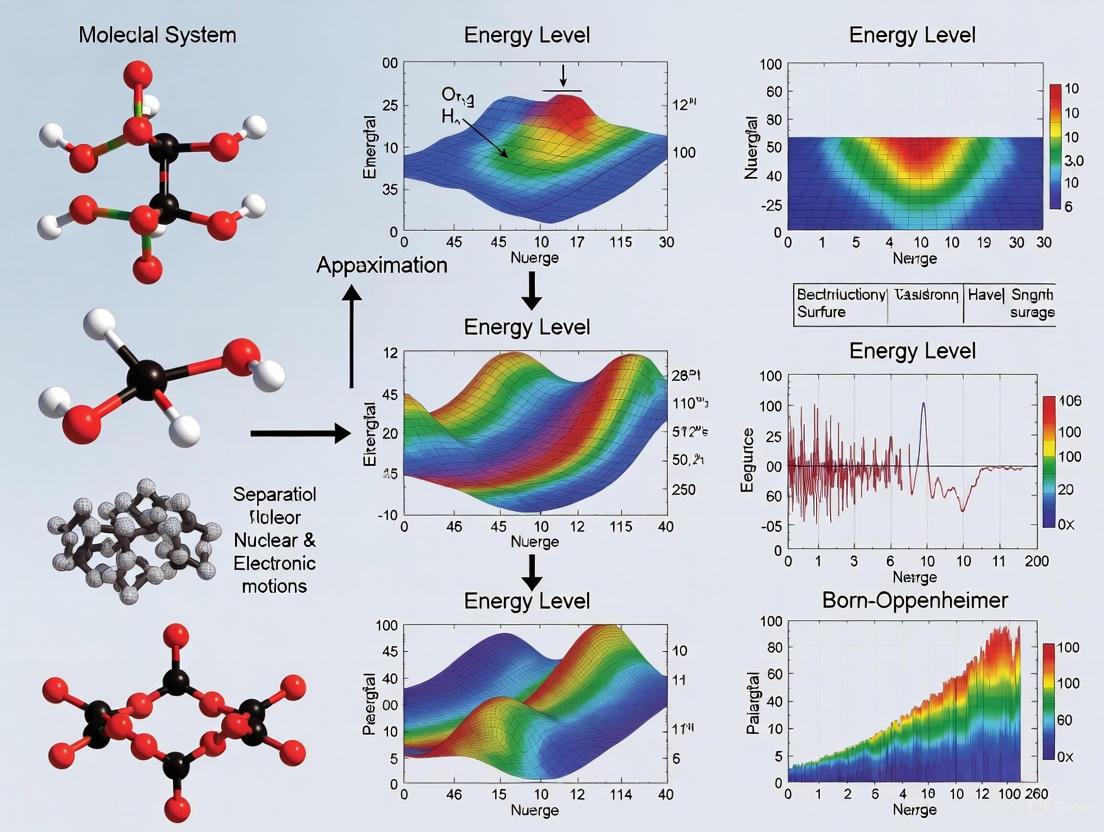

Figure 1: The logical workflow of the Born-Oppenheimer Approximation, showing the separation of the full quantum mechanical problem into consecutive electronic and nuclear steps.

Validity, Limitations, and Breakdown

The BO approximation is an excellent approximation for the vast majority of molecular systems in their electronic ground state under normal conditions. Its validity hinges on the condition that the potential energy surfaces for different electronic states are well separated [3] [1]: [ E0(\mathbf{R}) \ll E1(\mathbf{R}) \ll E_2(\mathbf{R}) \ll \cdots \quad \text{for all nuclear configurations } \mathbf{R}. ] When this condition holds, the coupling between electronic states (vibronic coupling) due to nuclear motion is negligible [3] [1].

However, the approximation breaks down in several important scenarios, which are active areas of research in quantum chemistry:

- Conical Intersections: Points where two potential energy surfaces become degenerate or nearly degenerate. These are critical in photochemistry and ultrafast relaxation processes [2].

- Light-Element Systems: Systems containing very light nuclei, such as hydrogen or helium atoms, where quantum nuclear effects (e.g., tunneling) are significant because the nuclei are not slow enough [3].

- Non-Adiabatic Processes: Processes like electron transfer or light-driven reactions (e.g., vision) where the motion of the nuclei is fast enough to cause a transition between electronic states [2].

In such cases, the off-diagonal elements of the nuclear kinetic energy operator, which are neglected in the simple BO approximation, become large and cannot be ignored [3]. Even when the BO approximation breaks down, it almost always serves as the fundamental starting point for more sophisticated computational methods.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Concepts and Computational Reagents

Table 2: Essential "Research Reagents" in Born-Oppenheimer-Based Computational Chemistry

| Concept/Tool | Function in Computational Molecular Modeling |

|---|---|

| Potential Energy Surface (PES) | A hyper-surface representing the electronic energy of a molecule as a function of its nuclear coordinates; it is the central "map" for understanding molecular structure, reactivity, and dynamics [3]. |

| Molecular Hamiltonian | The quantum mechanical operator corresponding to the total energy (kinetic + potential) of the molecular system; the BO approximation simplifies its structure [3] [7]. |

| Electronic Wavefunction, (\chi(\mathbf{r};\mathbf{R})) | Describes the quantum state of all electrons for a fixed nuclear geometry; its square gives the probability distribution of the electrons [3] [1]. |

| Nuclear Wavefunction, (\phi(\mathbf{R})) | Describes the quantum state of the nuclei moving on a single Potential Energy Surface; it encodes information about molecular vibrations and rotations [3] [1]. |

| Geometry Optimization | The computational process of iteratively adjusting nuclear coordinates to find the minimum on the Potential Energy Surface, yielding the molecule's most stable structure [6]. |

| 2,4-Dimethyl-3-hexanol | 2,4-Dimethyl-3-hexanol | High-Purity Reagent |

| n,n-Dimethyl-4-(prop-2-en-1-yl)aniline | n,n-Dimethyl-4-(prop-2-en-1-yl)aniline, CAS:51601-26-4, MF:C11H15N, MW:161.24 g/mol |

Legacy and Modern Applications

The Born-Oppenheimer approximation is far more than a mathematical convenience; it fundamentally shapes how chemists conceptualize molecules. It provides the quantum mechanical justification for the ball-and-stick model of molecules, where rigid nuclei (balls) are connected by a bonding framework (sticks), and for the very concept of a molecule having a defined shape [6] [2]. It establishes that chemistry is, at its core, governed by the behavior of electrons, which create the potential energy surfaces that guide the motion of nuclei during chemical reactions [2].

Today, the approximation forms the unquestioned foundation of computational quantum chemistry [2]. This field has grown exponentially, enabling researchers to:

- Design novel pharmaceuticals by predicting how drug candidates interact with biological targets [2].

- Develop new materials, such as more efficient photovoltaics, by modeling their electronic properties [2].

- Simulate reaction mechanisms and catalyst behavior without the need for costly and time-consuming laboratory experiments.

While new methods, including extensions like the recently proposed "Moving Born-Oppenheimer Approximation" and future calculations on quantum computers, are pushing the boundaries of the field [2] [9], the BO approximation remains the essential first step in virtually all quantum chemical computations. Over nine decades after its publication, the collaboration between a seasoned professor and his brilliant student continues to be a pillar of modern molecular science.

The Born-Oppenheimer (BO) approximation constitutes a foundational pillar in quantum chemistry and molecular physics, enabling the practical application of quantum mechanics to chemical systems. This approximation provides the theoretical justification for separating complex molecular motion into more manageable electronic and nuclear components, a concept that underpins most modern electronic structure calculations. Within the context of molecular systems research, particularly in drug development where accurate prediction of molecular structure and reactivity is paramount, the BO approximation allows researchers to compute molecular properties with feasible computational cost while maintaining physical accuracy. The core physical insight driving this approximation originates from the significant mass disparity between atomic nuclei and electrons, a fundamental property that dictates their relative dynamics and energy scales within molecular systems.

This whitepaper examines the physical principles underlying the Born-Oppenheimer approximation, focusing specifically on how the mass difference between nuclei and electrons enables the separation of their motions. We present quantitative analyses of mass and acceleration ratios, detailed mathematical formulations, and practical implications for computational chemistry in pharmaceutical research. By understanding both the capabilities and limitations of this approximation, researchers can make more informed decisions when selecting computational methods for investigating molecular structure, spectra, and reactivity in drug development applications.

The Physical Basis: Mass and Kinetics Disparity

Fundamental Mass Ratio Between Nuclei and Electrons

The primary physical insight underlying the Born-Oppenheimer approximation stems from the extraordinary mass difference between atomic nuclei and electrons. A proton's mass is roughly 2000 times greater than an electron's mass, and this ratio increases proportionally with nuclear mass [10] [11]. This mass disparity has profound implications for molecular dynamics, as particles of different masses respond to forces on dramatically different timescales.

The following table summarizes key mass and charge properties of fundamental particles relevant to molecular systems:

Table 1: Fundamental Particle Properties in Molecular Systems

| Particle Type | Mass (kg) | Relative Mass (proton=1) | Charge (C) | Charge-to-Mass Ratio (C/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electron | 9.11×10â»Â³Â¹ | ~1/1836 | -1.60×10â»Â¹â¹ | -1.76×10¹¹ |

| Proton | 1.67×10â»Â²â· | 1 | +1.60×10â»Â¹â¹ | 9.58×10â· |

| Neutron | 1.67×10â»Â²â· | 1 | 0 | 0 |

This mass disparity means that electrons, being significantly lighter, accelerate much more rapidly than nuclei when subjected to the same forces. According to Newton's second law (F=ma), for the same mutual attractive force between opposite charges, the acceleration of electrons is more than 1000 times greater than that of atomic nuclei [12]. This difference in acceleration leads to electrons completing many orbital cycles while nuclei undergo minimal displacement, effectively enabling the electronic motion to be considered separately from nuclear motion for a given molecular configuration.

Kinetics and Dynamics Consequences

The kinetic implications of this mass disparity are profound in molecular systems:

- Differential Response Timescales: Electrons respond almost instantaneously to changes in nuclear positions, while nuclei experience electrons as a averaged potential field

- Separable Energy Scales: Electronic transitions typically occur in the UV-visible range (1-10 eV), while nuclear vibrations and rotations occur at much lower energies (0.01-0.5 eV and 0.001-0.01 eV, respectively)

- Adiabatic Following: Electronic wavefunctions can adjust quasi-statically to slow nuclear motion, forming the basis for potential energy surfaces

The relationship between mass disparity and molecular dynamics can be visualized through the following conceptual diagram:

Figure 1: Logical flow from mass disparity to separable energy components in molecular systems

Mathematical Formulation

Molecular Hamiltonian and BO Separation

The complete molecular Hamiltonian for a system with M nuclei and N electrons can be written in atomic units as [10]:

[ \hat{H} = -\sum{A=1}^{M} \frac{1}{2MA} \nabla{\vec{RA}}^2 - \sum{i=1}^{N} \frac{1}{2} \nabla{\vec{ri}}^2 - \sum{A=1}^{M} \sum{i=1}^{N} \frac{ZA}{|\vec{RA} - \vec{ri}|} + \sum{i=1}^{N-1} \sum{j>i}^{N} \frac{1}{|\vec{ri} - \vec{rj}|} + \sum{A=1}^{M-1} \sum{B>A}^{M} \frac{ZA ZB}{|\vec{RA} - \vec{RB}|} ]

In this expression, the first term represents the nuclear kinetic energy, the second term the electronic kinetic energy, the third term the nuclear-electronic attraction, the fourth term the electron-electron repulsion, and the fifth term the nuclear-nuclear repulsion.

The Born-Oppenheimer approximation simplifies this complex Hamiltonian by recognizing that the nuclear kinetic energy terms (first term) can be neglected when solving for electronic wavefunctions, as nuclei are effectively stationary compared to electrons. This leads to a separation where:

[ \hat{H} = \hat{T}{\text{nuc}} + \hat{H}{\text{elec}} ]

The electronic Hamiltonian becomes:

[ \hat{H}{\text{elec}} = -\sum{i=1}^{N} \frac{1}{2} \nabla{\vec{ri}}^2 - \sum{A=1}^{M} \sum{i=1}^{N} \frac{ZA}{|\vec{RA} - \vec{ri}|} + \sum{i=1}^{N-1} \sum{j>i}^{N} \frac{1}{|\vec{ri} - \vec{rj}|} + \sum{A=1}^{M-1} \sum{B>A}^{M} \frac{ZA ZB}{|\vec{RA} - \vec{R_B}|} ]

The nuclear-nuclear repulsion term (\sum{A=1}^{M-1} \sum{B>A}^{M} \frac{ZA ZB}{|\vec{RA} - \vec{RB}|}) is treated as a constant within the electronic Schrödinger equation for fixed nuclear positions [10].

Wavefunction Separation and Energy Additivity

The BO approximation allows the total molecular wavefunction to be expressed as a product of electronic and nuclear components:

[ \Psi{\text{total}} = \psi{\text{electronic}} \cdot \psi{\text{vibration}} \cdot \psi{\text{rotation}} ]

This separation leads to corresponding additivity in the energy components:

[ E{\text{total}} = E{\text{electronic}} + E{\text{vibrational}} + E{\text{rotational}} ]

This additive approach enables the hierarchical calculation of molecular properties, where the electronic energy is computed for fixed nuclear positions, followed by the treatment of nuclear motion as perturbations on the resulting potential energy surface.

Computational Methodologies and Research Applications

Standard Implementation Protocol

The practical implementation of the Born-Oppenheimer approximation in computational chemistry follows a well-established workflow:

Table 2: Computational Workflow Leveraging the Born-Oppenheimer Approximation

| Step | Procedure | Key Equations/Concepts | Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Nuclear Coordinate Fixation | Treat nuclear positions ( \vec{R_A} ) as parameters rather than dynamic variables | ( \vec{R_A} = \text{constant} ) | Molecular geometry |

| 2. Electronic Structure Calculation | Solve electronic Schrödinger equation for fixed nuclei | ( \hat{H}{\text{elec}} \psi{\text{elec}} = E{\text{elec}} \psi{\text{elec}} ) | Electronic wavefunction and energy |

| 3. Potential Energy Surface (PES) Construction | Repeat electronic calculation at multiple nuclear configurations | ( E{\text{elec}}({\vec{RA}}) ) | Multidimensional PES |

| 4. Nuclear Motion Treatment | Solve nuclear Schrödinger equation on PES | ( [\hat{T}{\text{nuc}} + E{\text{elec}}({\vec{RA}})] \psi{\text{nuc}} = E{\text{total}} \psi{\text{nuc}} ) | Vibrational/rotational states |

| 5. Property Calculation | Compute expectation values using total wavefunction | ( \langle \Psi{\text{total}} | \hat{O} | \Psi{\text{total}} \rangle ) | Molecular properties |

This computational workflow enables the efficient calculation of molecular structures, energies, and spectroscopic properties that would be intractable without the separation of electronic and nuclear motions.

Advanced Extensions: Cavity Born-Oppenheimer Approximation

Recent advances have extended the BO approximation to new domains, particularly in quantum electrodynamics. The Cavity Born-Oppenheimer (CBO) approximation has been developed to describe molecules interacting with quantized electromagnetic fields in optical cavities [13]. This approach self-consistently includes the effect of cavity modes on the electronic ground state, going beyond simple models that couple molecules to cavities via ground-state dipole moments.

The CBO approximation demonstrates how the fundamental principles of separability derived from mass disparity can be extended to more complex systems, though it requires specialized electronic structure methods beyond standard quantum chemistry packages. Recent work has shown that CBO energies and spectra can be recovered to high accuracy using out-of-cavity quantities from standard electronic structure calculations, providing a practical alternative to full CBO implementations [13].

Limitations and Breakdown Scenarios

Conditions for BO Approximation Failure

Despite its widespread utility, the Born-Oppenheimer approximation fails under specific conditions where the assumption of separable electronic and nuclear motions breaks down. Key failure scenarios include:

- Conical Intersections: Points where electronic potential energy surfaces become degenerate or nearly degenerate

- Nonadiabatic Transitions: Processes involving rapid nuclear motion that prevents electrons from adiabatically following

- Vibronic Coupling: Systems where specific vibrational modes strongly couple to electronic states

- Low-Mass Nuclear Systems: Molecules containing hydrogen or muonic atoms where nuclear quantum effects become significant

Under these conditions, the approximation that electrons instantaneously adjust to nuclear motion becomes invalid, requiring more sophisticated treatments that explicitly account for nonadiabatic effects [10].

Detection and Remediation Strategies

Table 3: Identifying and Addressing BO Approximation Breakdown

| Breakdown Indicator | Physical Manifestation | Computational Signature | Remediation Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conical Intersections | Photochemical reaction pathways, ultrafast decay | Degenerate or nearly degenerate electronic states | Nonadiabatic molecular dynamics, diabatization |

| Nonadiabatic Couplings | Electron transfer reactions, intersystem crossing | Large nonadiabatic coupling matrix elements | Surface hopping, exact factorization |

| Vibronic Coupling | Jahn-Teller effects, spectral band shapes | Significant geometry dependence of electronic states | Vibronic coupling models, dressed states |

| Significant Nuclear Quantum Effects | Hydrogen bonding, proton tunneling | Anharmonic vibrational spectra, isotope effects | Multicomponent quantum chemistry methods [10] |

The breakdown conditions and relationships can be visualized as:

Figure 2: Conditions leading to Born-Oppenheimer approximation breakdown and resolution approaches

When nonadiabatic effects cannot be neglected, researchers must employ methods that go beyond the BO approximation. These include:

- Nonadiabatic Dynamics: Surface hopping, multiple spawning techniques

- Exact Factorization: Treating the nuclear wavefunction as exactly factoring the total wavefunction

- Multicomponent Quantum Chemistry: Treating specified nuclei (typically hydrogens) quantum mechanically on equal footing with electrons [10]

- Diabatic Representations: Using electronic basis states that vary slowly with nuclear coordinates

These advanced methods come with significantly increased computational cost but are essential for accurately describing processes involving multiple electronic states or significant nuclear quantum effects.

Research Tools and Computational Implementations

The practical application of the Born-Oppenheimer approximation in molecular systems research requires specialized computational tools and theoretical frameworks:

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Born-Oppenheimer Based Calculations

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function/Role | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electronic Structure Methods | Hartree-Fock, DFT, CCSD(T), MCSCF | Solve electronic Schrödinger equation for fixed nuclei | Varying accuracy/computational cost tradeoffs |

| Nonadiabatic Coupling Calculators | Numerical gradient methods, analytic NAC | Compute coupling between electronic states | Essential for detecting BO breakdown |

| Potential Energy Surface Constructors | Grid-based, interpolation methods | Build multidimensional PES from electronic calculations | Foundation for nuclear dynamics |

| Vibration-Rotation Solvers | Variational methods, perturbation theory | Compute nuclear motion on PES | Predict spectroscopic properties |

| Non-BO Dynamics Packages | Surface hopping, MCTDH | Simulate dynamics beyond BO approximation | Treat nonadiabatic processes |

Emerging Directions and Research Frontiers

Current research continues to expand the applications and extensions of the Born-Oppenheimer framework:

- Non-BO Calculation Methods: Development of appropriate basis functions for non-BO calculations that treat both nuclei and electrons on equal footing [10]

- Cavity Quantum Electrodynamics: Extension of BO principles to molecular systems strongly coupled to optical cavities [13]

- Machine Learning Potentials: Using machine learning to represent potential energy surfaces with BO-level accuracy but greatly reduced computational cost

- Nuclear Quantum Effects: Incorporation of nuclear quantum fluctuations in molecular dynamics while maintaining computational efficiency

These emerging directions demonstrate how the core physical insight of mass disparity continues to inform new methodological developments in computational chemistry and molecular physics.

The Born-Oppenheimer approximation remains one of the most important concepts in theoretical chemistry, enabling practical quantum mechanical calculations of molecular systems by leveraging the fundamental mass disparity between nuclei and electrons. This physical insight - that electrons move much faster than nuclei due to their significantly smaller mass - permits the separation of electronic and nuclear motions, leading to tremendous simplifications in molecular quantum mechanics.

For researchers in molecular systems and drug development, understanding both the power and limitations of this approximation is crucial for selecting appropriate computational methods and interpreting results. While the BO approximation provides the foundation for most electronic structure calculations, awareness of its breakdown conditions ensures proper application to photochemical processes, systems with conical intersections, and molecules containing light atoms where nuclear quantum effects become significant.

As computational methods continue to evolve, the core physical insight of mass disparity will remain essential for developing new approaches that push beyond current limitations while maintaining computational feasibility for complex molecular systems relevant to pharmaceutical research and materials design.

The separation of the total molecular wavefunction is a cornerstone in quantum chemistry, enabling the practical computation of molecular properties by decoupling the intricate motions of electrons and nuclei. This approach is formally grounded in the Born-Oppenheimer approximation, a fundamental concept that simplifies the molecular Schrödinger equation. The physical basis for this separation lies in the significant mass disparity between nuclei and electrons; nuclei are thousands of times heavier than electrons, causing them to move much more slowly. Consequently, electrons can be considered to instantaneously adjust their distribution to any new configuration of the nuclei. This allows for the treatment of electronic motion as if the nuclei were fixed in space, providing a powerful framework for understanding molecular structure and spectroscopy [14] [15] [16].

Within this framework, the total energy of a molecule forms a potential energy surface upon which nuclear motion (vibrations and rotations) occurs. The mathematical separation of the wavefunction is critical for molecular spectroscopy, as it leads to a diagram of energy levels where electronic, vibrational, and rotational energies are, to a good approximation, additive. Electronic excitations typically occupy the ultraviolet and visible spectral regions, vibrational excitations the infrared, and rotational excitations the microwave region, thus organizing molecular spectroscopy in a hierarchical manner [14].

Mathematical Derivation of the Wavefunction Separation

The Molecular Hamiltonian and the Born-Oppenheimer Ansatz

The starting point is the total, non-relativistic molecular Hamiltonian, (\hat{H}{\text{total}}). For a molecule, this operator accounts for the kinetic energy of all nuclei ((\hat{T}n)) and all electrons ((\hat{T}e)), as well as the potential energy due to all Coulomb interactions between these particles: nucleus-nucleus ((V{nn})), electron-electron ((V{ee})), and electron-nucleus ((V{en})) [15].

[ \hat{H}{\text{total}} = \hat{T}n + \hat{T}e + V{nn} + V{ee} + V{en} ]

The time-independent Schrödinger equation is then (\hat{H}{\text{total}} \Psi{\text{total}}(\mathbf{r}, \mathbf{R}) = E{\text{total}} \Psi{\text{total}}(\mathbf{r}, \mathbf{R})), where (\mathbf{r}) and (\mathbf{R}) collectively represent the coordinates of all electrons and all nuclei, respectively. This equation is intractable to solve directly for any system with more than one electron. The Born-Oppenheimer approximation proposes a product form, or ansatz, for the total wavefunction [15]:

[ \Psi{\text{total}}(\mathbf{r}, \mathbf{R}) \approx \Psi{\text{el}}(\mathbf{r}; \mathbf{R}) \Psi_{\text{n}}(\mathbf{R}) ]

In this crucial step, (\Psi{\text{el}}(\mathbf{r}; \mathbf{R})) is the electronic wavefunction, which depends parametrically on the nuclear coordinates (\mathbf{R}). This means that for every fixed arrangement of the nuclei, (\Psi{\text{el}}) is a function only of the electron coordinates (\mathbf{r}). The function (\Psi_{\text{n}}(\mathbf{R})) is the nuclear wavefunction, describing the motion of the nuclei in the average field created by the electrons.

The Electronic and Nuclear Equations

Substituting the product ansatz into the full Schrödinger equation and making use of the heavy-mass approximation for the nuclei leads to a separation into two coupled equations. The first is the electronic Schrödinger equation, which is solved for a fixed nuclear configuration (\mathbf{R}) [15]:

[ \left( \hat{T}e + V{en} + V{ee} \right) \Psi{\text{el}}(\mathbf{r}; \mathbf{R}) = E{\text{el}}(\mathbf{R}) \Psi{\text{el}}(\mathbf{r}; \mathbf{R}) ]

Here, (E{\text{el}}(\mathbf{R})) is the electronic energy, which includes the kinetic energy of the electrons and all potential energies *except* the nucleus-nucleus repulsion, (V{nn}). The sum (U(\mathbf{R}) = E{\text{el}}(\mathbf{R}) + V{nn}(\mathbf{R})) defines the Born-Oppenheimer potential energy surface. This surface is a function of the nuclear coordinates and governs the motion of the nuclei.

The second equation is the nuclear Schrödinger equation [15]:

[ \left( \hat{T}n + U(\mathbf{R}) \right) \Psi{\text{n}}(\mathbf{R}) = E{\text{total}} \Psi{\text{n}}(\mathbf{R}) ]

In this equation, the nuclei move on the potential energy surface (U(\mathbf{R})) generated by the electrons. The solutions (\Psi{\text{n}}(\mathbf{R})) describe the vibrational and rotational states of the molecule, with (E{\text{total}}) being the total internal energy.

Table 1: Key Components of the Separated Wavefunction Formalism

| Component | Symbol | Role and Description | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Wavefunction | (\Psi_{\text{total}}(\mathbf{r}, \mathbf{R})) | Complete description of the molecular quantum state. | |

| Electronic Wavefunction | (\Psi_{\text{el}}(\mathbf{r}; \mathbf{R})) | Describes electron distribution for fixed nuclei; parametric in (\mathbf{R}). | |

| Nuclear Wavefunction | (\Psi_{\text{n}}(\mathbf{R})) | Describes vibration and rotation of nuclei on a potential energy surface. | |

| Potential Energy Surface | (U(\mathbf{R})) | Effective potential for nuclear motion, (U = E{\text{el}} + V{nn}). | |

| Vibronic Coupling | (\langle \Psi_{\text{el}} | \nabla{\mathbf{R}} \Psi{\text{el}} \rangle) | Non-adiabatic coupling term, neglected in the simple BO approximation [14]. |

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and the key relationships established by the Born-Oppenheimer approximation:

Computational Methodologies and Protocols

The Linear Combination of Atomic Orbitals (LCAO) Approach

For practical computations, the electronic wavefunction (\Psi{\text{el}}) must be approximated. A standard approach is the Linear Combination of Atomic Orbitals (LCAO), which constructs molecular orbitals ((\psi{\text{mo}})) from a basis set of atomic orbitals ((\phi_p)) centered on the constituent atoms [17]:

[ \psi{\text{mo}}(\vec{r}) = \sum{p=1}^{N} cp \phip(\vec{r} - \vec{r}_a) ]

Here, (c_p) are coefficients determined by solving the Schrödinger equation, and the sum runs over all selected atomic orbitals (N). A typical choice for the basis set includes the occupied atomic orbitals of the isolated atoms. For a water molecule, for instance, one might use the 1s, 2s, and 2p orbitals of oxygen and the 1s orbitals of the two hydrogen atoms, resulting in a basis set size of (N=7) [17].

The Roothaan Equations and Matrix Formulation

Applying the LCAO method within the electronic Schrödinger equation leads to the Roothaan equations. These are derived by multiplying the Schrödinger equation from the left by each atomic orbital and integrating over all space, resulting in a generalized eigenvalue problem [17]:

[ \mathbf{H} \vec{c} = E \mathbf{S} \vec{c} ]

In this matrix equation:

- (\mathbf{H}) is the Hamiltonian matrix, with elements (H{pq} = \langle \phip | \hat{H}{\text{el}} | \phiq \rangle).

- (\mathbf{S}) is the overlap matrix, with elements (S{pq} = \langle \phip | \phi_q \rangle), which accounts for the non-orthogonality of atomic orbitals on different centers.

- (\vec{c}) is the vector of molecular orbital coefficients.

- (E) is the orbital energy.

Solving this equation numerically yields (N) molecular orbital energies and their corresponding wavefunctions. The Hamiltonian and overlap matrices often exhibit a block diagonal structure due to symmetry, which can be exploited to simplify the computational problem [17].

Table 2: Summary of a Sample LCAO Calculation for Carbon Monoxide

| Computational Aspect | Description | Value / Example from CO calculation [17] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basis Set | Atomic orbitals used in the expansion. | 2s, 2p orbitals for C and O (8 orbitals total). | ||

| Hamiltonian Matrix Element | Example coupling energy between orbitals. | (H{12} = \langle \phi{C_{2s}} | \hat{H} | \phi{O{2s}} \rangle = -52.64) eV |

| Overlap Matrix Element | Non-orthogonality between orbitals. | (S{12} = \langle \phi{C_{2s}} | \phi{O{2s}} \rangle = 0.47) | |

| Matrix Structure | How symmetry simplifies the problem. | 4x4 block (2s, 2px), 2x2 block (2py), 2x2 block (2p_z). | ||

| Effective Nuclear Charge | (Z_{\text{eff}}) parameter in model potential. | (Z^C{\text{eff}}=3.25), (Z^O{\text{eff}}=4.55) |

Advanced Considerations: Beyond the Simple Separation

The simple product ansatz is an approximation. The full derivation shows that additional terms, known as vibronic coupling terms, are neglected. These terms describe the coupling between nuclear and electronic motion and are proportional to (\langle \Psi{\text{el}} | \nabla{\mathbf{R}} \Psi{\text{el}} \rangle) and (\langle \Psi{\text{el}} | \nabla{\mathbf{R}}^2 \Psi{\text{el}} \rangle) [14] [15]. They are typically small, on the order of (1/M_{\alpha} \approx 10^{-3}), compared to the electronic and nuclear energies, which justifies their neglect in the standard Born-Oppenheimer approximation. However, they become critical in several important phenomena.

A more rigorous, exact formulation of the total wavefunction that can handle these couplings is a sum over products of electronic and nuclear functions [14]:

[ \Psi{\text{total}}(\mathbf{r}, \mathbf{R}) = \sum{k}^{\infty} \psik(\mathbf{r}; \mathbf{R}) fk(\mathbf{R}) ]

Here, the sum runs over all electronic states (k). This expansion is the starting point for treating non-adiabatic processes, where the coupling between different electronic states (e.g., (k) and (l)) via the nuclear motion, (\langle \psil | \nabla{\mathbf{R}} \psik \rangle \nabla{\mathbf{R}}), is significant [14]. These processes are central to photochemical reactions, where a molecule in an excited electronic state can transition to a different electronic state through a nuclear configuration known as a conical intersection, which acts as a efficient funnel back to the ground state [14].

The following diagram illustrates the advanced concepts that arise when the simple separation breaks down:

Table 3: Key Computational Tools and Concepts for Wavefunction Calculations

| Tool / Concept | Category | Function and Role in Research | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Born-Oppenheimer Approximation | Theoretical Foundation | Enables separation of electronic and nuclear motions, simplifying the problem from a many-body to a single-body electronic problem. | |

| Basis Sets | Computational Resource | Sets of atomic orbitals (e.g., 6-31G*, cc-pVDZ) used to expand molecular orbitals in LCAO calculations. Choice affects accuracy and cost. | |

| Potential Energy Surface (PES) | Conceptual/Computational Model | A map of electronic energy as a function of nuclear coordinates. Essential for predicting molecular geometry, reaction paths, and vibrational frequencies. | |

| Non-Adiabatic Coupling Terms | Mathematical Operator | Quantities like (\langle \psi_l | \nabla{\mathbf{R}} \psik \rangle) that couple electronic states. Their calculation is essential for simulating processes beyond the BO approximation. |

| Diabatic Transformation | Computational Algorithm | A mathematical technique to transform the Hamiltonian into a basis where non-adiabatic couplings are minimized, simplifying dynamics simulations [16]. | |

| Conical Intersection | Critical Point on PES | A point where two electronic potential energy surfaces become degenerate, serving as a funnel for ultrafast radiationless transitions between states [14]. |

The Born-Oppenheimer (BO) approximation represents a cornerstone of quantum chemistry, without which the computation of molecular wavefunctions for all but the smallest molecules would be intractable [3]. This approximation, proposed in the early days of quantum mechanics by Max Born and his 23-year-old graduate student J. Robert Oppenheimer, enables the separation of electronic and nuclear motions based on the significant mass difference between these particles [1]. The approximation is particularly indispensable for researchers in molecular systems research and drug development, where understanding molecular structure, reactivity, and interactions at the quantum level is essential for rational drug design. Within this framework, the clamped-nuclei approximation constitutes the crucial first step, providing the foundation for generating potential energy surfaces that guide our understanding of molecular structure, stability, and reactivity.

Foundational Principles

The Physical Basis for Separation

The theoretical justification for the Born-Oppenheimer approximation stems from the substantial mass disparity between atomic nuclei and electrons. The lightest nucleus (the hydrogen nucleus) is approximately 1836 times heavier than an electron, and this mass ratio increases for heavier elements [3]. This mass difference translates to a significant divergence in the timescales of their motions: electrons typically undergo periodic motions on the timescale of 10â»Â¹â· seconds, while nuclear vibrations occur much more slowly, around 10â»Â¹â´ seconds [18]. This temporal separation allows electrons to adjust almost instantaneously to changes in nuclear configuration—as the slow-moving nuclei traverse their potential energy landscape, the electrons remain in a stationary state corresponding to the instantaneous nuclear geometry.

Some research suggests that the form of the Coulomb interaction between particles, rather than solely the mass ratio, may be responsible for the successful separation [19]. Nevertheless, the practical consequence is that the nuclear kinetic energy can initially be neglected in the electronic structure calculation, leading to what is universally known as the clamped-nuclei approximation.

The Mathematical Framework

The complete molecular Hamiltonian encompasses kinetic energy operators for all electrons and nuclei, along with the complete set of Coulomb interactions:

[ H = \sumi \left[- \frac{\hbar^2}{2me} \frac{\partial^2}{\partial qi^2} \right] + \frac{1}{2} \sum{j\ne i} \frac{e^2}{r{i,j}} - \sum{a,i} \frac{Zae^2}{r{i,a}} + \suma \left[- \frac{\hbar^2}{2ma} \frac{\partial^2}{\partial qa^2}\right] + \frac{1}{2} \sum{b\ne a} \frac{ZaZb e^2}{r_{a,b}} ]

In this expression, (qi) represent electronic coordinates, (qa) represent nuclear coordinates, (Za) are atomic numbers, (ma) are nuclear masses, (me) is the electron mass, and (r{i,j}), (r{i,a}), and (r{a,b}) represent electron-electron, electron-nucleus, and nucleus-nucleus distances, respectively [18].

Table: Components of the Molecular Hamiltonian

| Component | Mathematical Expression | Physical Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Electronic Kinetic Energy | (-\sumi \frac{\hbar^2}{2me} \nabla_i^2) | Kinetic energy of all electrons |

| Electron-Electron Repulsion | (\frac{1}{2} \sum{i \neq j} \frac{e^2}{r{ij}}) | Coulomb repulsion between electrons |

| Electron-Nucleus Attraction | (-\sum{a,i} \frac{Zae^2}{r_{i,a}}) | Coulomb attraction between electrons and nuclei |

| Nuclear Kinetic Energy | (-\suma \frac{\hbar^2}{2ma} \nabla_a^2) | Kinetic energy of all nuclei |

| Nuclear-Nuclear Repulsion | (\frac{1}{2} \sum{a \neq b} \frac{ZaZb e^2}{r{a,b}}) | Coulomb repulsion between nuclei |

The Clamped-Nuclei Approximation

Theoretical Formulation

The clamped-nuclei approximation constitutes the first step in the Born-Oppenheimer procedure. In this step, the nuclear kinetic energy operator is omitted from the total molecular Hamiltonian [1] [3]. The remaining electronic Hamiltonian takes the form:

[ H{\text{electronic}} = \sumi \left[- \frac{\hbar^2}{2me} \frac{\partial^2}{\partial qi^2} \right] + \frac{1}{2} \sum{j\ne i} \frac{e^2}{r{i,j}} - \sum{a,i} \frac{Zae^2}{r{i,a}} + \frac{1}{2} \sum{b\ne a} \frac{ZaZb e^2}{r_{a,b}} ]

It is crucial to note that while the nuclear kinetic energy is neglected, the nuclear coordinates still appear parametrically in the electron-nucleus attraction terms ((r{i,a})) and the nuclear-nuclear repulsion terms ((r{a,b})) [3]. The nuclei are effectively "clamped" at fixed positions in space, generating an electrostatic potential field in which the electrons move. This fixed nuclear configuration is often, though not exclusively, chosen to be the equilibrium geometry of the molecule.

The Electronic Schrödinger Equation

With the nuclei fixed in a specific configuration, we solve the electronic Schrödinger equation:

[ H{\text{e}} \chik(\mathbf{r}; \mathbf{R}) = Ek(\mathbf{R}) \chik(\mathbf{r}; \mathbf{R}) ]

where (\chik(\mathbf{r}; \mathbf{R})) represents the electronic wavefunction for the k-th electronic state, which depends explicitly on the electronic coordinates (\mathbf{r}) and parametrically on the nuclear coordinates (\mathbf{R}) [1] [3]. The energy eigenvalue (Ek(\mathbf{R})) constitutes the electronic energy for the k-th state at nuclear configuration (\mathbf{R}).

The parametric dependence of the electronic wavefunction on nuclear coordinates is a subtle but crucial aspect of the approximation. For instance, in the molecular orbital approach, the LCAO coefficients change value as the nuclear geometry changes, thereby altering the functional form of the molecular orbitals [1]. This dependence gives rise to non-adiabatic coupling terms that become important when the Born-Oppenheimer approximation breaks down.

Diagram: Born-Oppenheimer Approximation Workflow. The process begins with selecting a molecular system and proceeds through the two key stages of the approximation: solving the electronic problem with clamped nuclei, then solving the nuclear motion problem on the resulting potential energy surface.

Potential Energy Surfaces

Conceptual Foundation and Generation

The potential energy surface (PES) represents a central concept in quantum chemistry that emerges directly from the clamped-nuclei approximation. Mathematically, a PES is defined as the electronic energy (E_k(\mathbf{R})) plotted as a function of the nuclear coordinates (\mathbf{R}) for a specific electronic state k [3]. To generate a PES, researchers systematically repeat the electronic structure calculation at numerous different nuclear configurations, effectively "mapping" the electronic energy across the nuclear coordinate space [1] [18].

The process of recomputing electronic wavefunctions for infinitesimally changing nuclear geometries resembles the conditions for the adiabatic theorem in quantum mechanics, which is why this procedure is often referred to as the adiabatic approximation and the resulting PES is termed an adiabatic surface [3] [20]. This surface contains contributions from electron kinetic energies, interelectronic repulsions, and electron-nuclear attractions, with the nuclear-nuclear repulsion included as a classical additive term.

Critical Points and Chemical Significance

Potential energy surfaces exhibit characteristic topological features that correspond to chemically significant structures. Minima on the PES represent stable molecular configurations, with the global minimum corresponding to the most stable structure [18]. First-order saddle points connect these minima and represent transition states for chemical reactions [18]. The ability to locate and characterize these critical points forms the basis for computational studies of molecular structure, reactivity, and spectroscopy.

Table: Computational Complexity Reduction via Born-Oppenheimer Approximation

| Aspect | Full Quantum Treatment | With BO Approximation | Reduction Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Benzene Molecule Coordinates | 162 (126 electronic + 36 nuclear) | Solved sequentially | N/A |

| Electronic Problem | N/A | 126 variables solved N times | N/A |

| Nuclear Problem | N/A | 36 variables solved once | N/A |

| Computational Complexity Estimate | ~162² = 26,244 | ~126²·N + 36² | Significant reduction |

For a molecule like benzene with 12 nuclei and 42 electrons, the full Schrödinger equation requires solving a partial differential eigenvalue equation in 162 variables (126 electronic + 36 nuclear coordinates) [1] [3]. The BO approximation reduces this to solving an electronic problem in 126 variables multiple times (for different nuclear configurations), followed by a nuclear problem in 36 variables just once [1]. Since computational complexity typically increases faster than the square of the number of coordinates, this represents a substantial simplification [1].

Methodological Protocols and Research Tools

Computational Implementation Protocol

The practical implementation of the clamped-nuclei approximation follows a well-established protocol:

Selection of Nuclear Configuration: Choose an initial nuclear configuration R, often starting from an experimental geometry or chemical intuition.

Electronic Structure Calculation: At this fixed nuclear geometry, solve the electronic Schrödinger equation approximately using computational methods such as:

- Hartree-Fock (HF) theory

- Density Functional Theory (DFT)

- Coupled Cluster (CC) methods

- Configuration Interaction (CI) approaches

Energy Evaluation: Compute the electronic energy (E_k(\mathbf{R})) for the desired electronic state (typically the ground state, k=0).

Geometry Perturbation: Systematically vary the nuclear coordinates (\mathbf{R}) in small increments to explore different molecular configurations.

Surface Mapping: Repeat steps 2-4 to generate a sufficient number of points to construct the complete potential energy surface.

Surface Fitting: Interpolate between calculated points using analytic functions to create a continuous potential energy surface [21].

This protocol is implemented in virtually all quantum chemistry software packages, including Gaussian, GAMESS, ORCA, and NWChem, making it accessible to researchers across chemistry, materials science, and drug discovery.

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table: Essential Computational Tools for Born-Oppenheimer Implementation

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in Clamped-Nuclei Research |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Chemistry Software | Gaussian, GAMESS, ORCA, NWChem | Implements electronic structure methods with fixed nuclei |

| Basis Sets | Pople-style (e.g., 6-31G*), Dunning's cc-pVXZ | Provides mathematical basis for expanding electronic wavefunctions |

| Electronic Structure Methods | HF, DFT, MP2, CCSD(T) | Solves electronic Schrödinger equation for clamped nuclei |

| Geometry Optimization Algorithms | Berny, EF, GDIIS | Locates stationary points on PES |

| Frequency Calculation Codes | Analytical derivatives, numerical differentiation | Characterizes stationary points |

| Visualization Software | Molden, GaussView, Jmol | Visualizes molecular structures and PES |

Limitations and Breakdown of the Approximation

Theoretical Limitations

Despite its remarkable utility, the Born-Oppenheimer approximation possesses significant limitations. The approach introduces a classical assumption (precisely fixed nuclear positions) into a fundamentally quantum framework, which contradicts the Heisenberg uncertainty principle for quantum particles [22]. More practically, the approximation fails when two or more potential energy surfaces approach each other or become degenerate [1] [3]. Under these conditions, the off-diagonal coupling terms involving nuclear momenta:

[ \langle \chik | \frac{\partial}{\partial RA} | \chi_m \rangle \quad (k \neq m) ]

which are normally neglected, become significant and can no longer be ignored [1] [3]. This breakdown occurs because the electronic wavefunction can no longer adjust adiabatically to nuclear motion when electronic states are close in energy.

Practical Consequences and Solutions

In practical terms, the BO approximation breaks down in numerous chemically important situations, including:

- Conical intersections between potential energy surfaces

- Avoided crossings where surfaces come close together

- Systems with Jahn-Teller distortions

- Rydberg states where electron motion is slower and more diffuse [18]

- Charge transfer processes

When faced with these scenarios, researchers must turn to more sophisticated treatments that explicitly account for non-adiabatic effects. These include:

- Diabatic representations where nuclear momentum couplings are minimized

- Direct solution of the coupled nuclear motion equations

- Surface hopping methods for molecular dynamics

- Exact factorization approaches for electron-nuclear dynamics

Applications in Molecular Systems Research and Drug Development

The clamped-nuclei approximation and the resulting potential energy surfaces find extensive application in pharmaceutical research and molecular systems design. Key applications include:

Molecular Structure Determination: Locating minima on the PES enables prediction of molecular geometry, conformational preferences, and stereoelectronic effects that influence drug-receptor interactions.

Reaction Pathway Analysis: Tracing minimum energy paths between reactants, transition states, and products facilitates mechanistic studies of enzymatic reactions and metabolic transformations.

Vibrational Spectroscopy Prediction: The second derivatives of the PES at minima provide force constants for predicting vibrational frequencies and interpreting IR and Raman spectra of drug molecules.

Binding Affinity Estimation: PES mapping for host-guest systems and drug-receptor complexes enables quantitative assessment of intermolecular interactions and binding energies.

Solvation Effects Modeling: Incorporating implicit or explicit solvent models into the clamped-nuclei framework allows researchers to study environmental effects on molecular structure and reactivity.

The computational efficiency afforded by the Born-Oppenheimer approximation makes these applications feasible for biologically relevant systems, bridging the gap between accurate quantum mechanical description and practical computational feasibility in drug discovery pipelines.

The clamped-nuclei approximation provides an essential foundation for modern computational chemistry and molecular physics. By separating the complex coupled motion of electrons and nuclei, this approach enables the calculation of potential energy surfaces that illuminate molecular structure, dynamics, and reactivity. While the approximation has limitations, particularly when electronic states are nearly degenerate, it remains the starting point for virtually all quantum chemical calculations on molecular systems. For researchers in drug development and molecular systems research, mastery of these concepts enables rational design of molecular agents with tailored properties and functions, demonstrating the enduring legacy of Born and Oppenheimer's seminal insight nearly a century after its introduction.

The adiabatic principle, most famously embodied by the Born-Oppenheimer (BO) approximation, forms the cornerstone of our modern understanding of molecules. It provides the crucial simplification that enables the conceptualization and computation of molecular structure, dynamics, and reactivity. This principle hinges on the significant mass disparity between electrons and nuclei, which dictates a corresponding disparity in their timescales of motion. Due to their light mass, electrons move much faster than nuclei. The adiabatic principle posits that electrons instantaneously adjust to any change in nuclear configuration, effectively "following" the nuclei as they move [1] [23]. This separation of motion allows for the powerful concept of potential energy surfaces (PESs)— landscapes of electronic energy upon which nuclear dynamics unfold—which underpin nearly all interpretations in quantum chemistry and molecular physics [23]. This whitepaper details the theoretical foundation, computational implementation, and limitations of this fundamental principle, framing it within ongoing research efforts to understand and model molecular systems with high accuracy.

Theoretical Foundation of the Born-Oppenheimer Approximation

The Born-Oppenheimer approximation is a specific application of the broader adiabatic principle to molecular systems [1]. The derivation begins with the total molecular Hamiltonian, (\hat{H}_{\text{total}}), which includes the kinetic energy operators for all electrons and nuclei, as well as all Coulombic potential energy terms for electron-electron, nucleus-nucleus, and electron-nucleus interactions [1].

The approximation proceeds in two key steps:

Clamped-Nuclei Electronic Schrödinger Equation: The nuclear kinetic energy is initially neglected. For a fixed nuclear configuration (\mathbf{R}), one solves the electronic Schrödinger equation: [ \hat{H}{\text{el}}(\mathbf{r}; \mathbf{R}) \chik(\mathbf{r}; \mathbf{R}) = Ek(\mathbf{R}) \chik(\mathbf{r}; \mathbf{R}) ] Here, (\mathbf{r}) represents the electronic coordinates, (\chik(\mathbf{r}; \mathbf{R})) is the electronic wavefunction for the (k)-th state, and (Ek(\mathbf{R})) is the corresponding electronic energy, which depends parametrically on (\mathbf{R}) [1]. The function (E_k(\mathbf{R})) defines the adiabatic potential energy surface.

Nuclear Schrödinger Equation: The total molecular wavefunction is written as a product ansatz, (\Psi(\mathbf{r}, \mathbf{R}) = \chik(\mathbf{r}; \mathbf{R}) \phi(\mathbf{R})), and substituted into the full molecular Schrödinger equation. This leads to an equation for the nuclear wavefunction (\phi(\mathbf{R})) moving on the PES (Ek(\mathbf{R})) provided by the electrons: [ [\hat{T}{\text{n}} + Ek(\mathbf{R})] \phi(\mathbf{R}) = E \phi(\mathbf{R}) ] where (\hat{T}_{\text{n}}) is the nuclear kinetic energy operator [1].

The validity of this separation requires that the PESs are well-separated, meaning (E0(\mathbf{R}) \ll E1(\mathbf{R}) \ll E_2(\mathbf{R}) \ll \cdots) for all (\mathbf{R}) [1]. When this condition holds, non-adiabatic couplings—terms that arise from the nuclear momentum operator acting on the electronic wavefunction—are negligible.

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and the key outcome of applying the Born-Oppenheimer approximation.

Mathematical Formalism and Key Operators

The adiabatic approximation is quantified through a specific set of mathematical operators and terms. The following table summarizes the core components of the molecular Hamiltonian and the key quantities that emerge from the BO approximation.

Table 1: Key mathematical operators and quantities in the Born-Oppenheimer framework.

| Symbol | Name | Mathematical Expression / Description | Physical Significance | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ( \hat{H}_{\text{total}} ) | Total Molecular Hamiltonian | ( \hat{T}n + \hat{H}{\text{el}} ) | Governs the complete quantum dynamics of the molecule [1]. | ||

| ( \hat{H}_{\text{el}} ) | Electronic Hamiltonian | ( -\sumi \frac{1}{2}\nablai^2 - \sum{i,A}\frac{ZA}{r{iA}} + \sum{i>j}\frac{1}{r{ij}} + \sum{B>A}\frac{ZA ZB}{R_{AB}} ) | Determines the electronic energy for a fixed nuclear configuration (\mathbf{R}) [1]. | ||

| ( E_k(\mathbf{R}) ) | Adiabatic Potential Energy | Eigenvalue of ( \hat{H}{\text{el}} ): ( \hat{H}{\text{el}} \chik = Ek(\mathbf{R}) \chi_k ) | Forms the Potential Energy Surface (PES) on which nuclei move [1] [23]. | ||

| Non-Adiabatic Couplings | Derivative Couplings | ( \langle \chi_i | \nablaR \chij \rangle ), ( \langle \chi_i | \nablaR^2 \chij \rangle ) | Couple adiabatic states; responsible for BO breakdown. Divergent at conical intersections [24]. |

| ( \mathcal{F}_{ij} ) | Electronic Quantum Geometric Tensor | Abelian (1 state) or non-Abelian (>1 states) tensor | Encodes quantum geometry (Berry curvature & quantum metric) of the electronic states [24]. |

A critical development beyond the standard BO view is the understanding that the electronic wavefunction's variation with nuclear coordinates is not just a correction, but a fundamental quantum geometric property. The Electronic Quantum Geometric Tensor captures this, with its imaginary part (Berry curvature) governing geometric phase effects and its real part (quantum metric) influencing nuclear motion as a scalar potential [24]. This tensor becomes singular at points of electronic degeneracy, which is the root cause of the BO approximation's breakdown in these regions.

Methodologies: From Ab Initio Calculations to Quantum Dynamics

Standard Electronic Structure Protocol

The practical application of the BO approximation involves a well-established computational workflow, often referred to as ab initio quantum chemistry.

Table 2: Key research reagents and computational components in electronic structure theory.

| Research Reagent / Component | Function / Description | |

|---|---|---|

| Atomic Orbital Basis Set | A set of one-electron functions centered on atomic nuclei, used to construct molecular orbitals (e.g., Gaussian-type orbitals, plane waves). | |

| Molecular Orbital Coefficients | Coefficients determined via the Hartree-Fock or Density Functional Theory (DFT) procedure that define the electronic wavefunction. | |

| Electronic Structure Code | Software (e.g., Gaussian, PSI4, Q-Chem, VASP) that implements the numerical solution of the electronic Schrödinger equation. | |

| Non-Adiabatic Coupling Vectors | Vectors calculated as ( \langle \chi_i | \nablaR \chij \rangle ), which are critical for simulating non-adiabatic dynamics but are difficult to obtain [24]. |

| Global Electronic Overlap Matrix | A matrix of overlaps between electronic wavefunctions at different nuclear geometries, ( \langle \chii(\mathbf{R}a) | \chij(\mathbf{R}b) \rangle ), which encodes quantum geometric information without singularities [24]. |

Experimental Protocol: Constructing a Potential Energy Surface

- Geometry Selection: Choose a set of relevant nuclear configurations ({\mathbf{R}1, \mathbf{R}2, ..., \mathbf{R}_N}).

- Single-Point Energy Calculations: At each configuration (\mathbf{R}i), perform an electronic structure calculation to solve ( \hat{H}{\text{el}}(\mathbf{r}; \mathbf{R}i) \chi(\mathbf{r}; \mathbf{R}i) = E(\mathbf{R}i) \chi(\mathbf{r}; \mathbf{R}i) ). This typically involves a self-consistent field procedure to account for electron-electron repulsion.

- Surface Interpolation/Fitting: Connect the computed energies (E(\mathbf{R}_i)) to generate a continuous PES, which can be used for subsequent nuclear dynamics simulations.

Advanced Framework: Topological Quantum Molecular Dynamics

A modern approach that overcomes the limitations of the standard BO framework is Topological Quantum Molecular Dynamics. This method avoids the singularities of derivative couplings by leveraging the global electronic overlap matrix [24].

Methodology:

- Discrete Local Trivialization: The molecular fiber bundle (with the nuclear configuration space as the base and electronic Hilbert space as the fiber) is discretized using a finite set of electron-nuclear product states [24].

- Overlap Matrix Construction: The global electronic overlap matrix ( \mathbf{S} ), with elements ( S{ij} = \langle \chii(\mathbf{R}a) | \chij(\mathbf{R}_b) \rangle ), is computed. This matrix remains bounded and non-singular, unlike derivative couplings [24].

- Dynamics Propagation: Nuclear quantum dynamics is propagated using this overlap matrix, which fully encapsulates the quantum geometric tensor (Berry curvature and quantum metric). This provides a numerically exact, divergence-free framework for both adiabatic and non-adiabatic dynamics [24].

Breakdown of the Approximation and Non-Adiabatic Phenomena

The adiabatic principle fails when its core assumption—the clean separation of electronic and nuclear motion—is violated. This typically occurs when two adiabatic PESs come close in energy or intersect.

Table 3: Scenarios and consequences of Born-Oppenheimer approximation breakdown.

| Scenario | Description | Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Conical Intersections (CIs) | Points where two PESs become degenerate, forming a "seam" in the nuclear configuration space. Ubiquitous in polyatomic molecules [24] [25]. | Ultrafast non-adiabatic transitions, a key mechanism in photochemistry (e.g., photodissociation, isomerization) [25]. |

| Avoided Crossings | Regions where two PESs approach very closely but do not cross, due to coupling between them. | Enhanced probability of non-adiabatic transitions, governed by the Landau-Zener formula [23] [26]. |

| Light-Induced Coupling | Coupling of a molecule to a cavity mode in quantum electrodynamics (QED) can create Light-Induced Conical Intersections (LICIs) [25]. | Induces non-adiabaticity even in molecules and dimensions where it would not naturally occur, altering absorption spectra and dynamics [25]. |

Experimental Evidence: Non-Adiabatic Lifetime Measurements in Dâ‚‚ A compelling example of BO breakdown is seen in the lifetimes of rovibrational levels of molecular deuterium (Dâ‚‚). The experimental protocol and findings are as follows [27]:

- Objective: Measure the lifetimes of excited rovibronic levels of Dâ‚‚ near its dissociation limit and compare them with theoretical predictions.

- Methodology:

- Two-Photon Excitation: Dâ‚‚ molecules are excited from the ground state to high-lying EF ( ^1\Sigmag^+ ) levels via an intermediate level in the B ( ^1\Sigmau^+ ) state.

- Fluorescence Detection: The lifetime is measured by observing the time-resolved fluorescence decay in the near-UV–visible range (330–520 nm).

- Results & Analysis:

- The measured lifetimes disagreed strongly with calculations performed within the adiabatic approximation.

- The discrepancy was attributed to strong non-adiabatic mixing between the EF state and other singlet gerade states (e.g., GK, H, I, J states).

- When non-adiabatic couplings were included in the theoretical model, the calculated lifetimes showed significantly improved agreement with experiment, confirming the breakdown of the BO approximation for these states [27].

The following diagram visualizes the process of non-adiabatic transition at a conical intersection, the primary scenario for BO breakdown.

The adiabatic principle, as formalized by the Born-Oppenheimer approximation, remains an indispensable tool for conceptualizing and computing the properties of molecules. It provides the foundational justification for molecular structure, vibrational spectroscopy, and the very idea of a chemical reaction pathway. However, modern research increasingly focuses on phenomena beyond this approximation.

The frontier of molecular quantum dynamics involves developing methods that can accurately and efficiently describe non-adiabatic processes. The Topological Quantum Molecular Dynamics framework [24] represents a significant advance by replacing singular derivative couplings with a well-behaved electronic overlap matrix. Furthermore, new environments like optical cavities introduce novel forms of non-adiabatic coupling (LICIs), challenging the approximation even in simple systems [25]. For researchers in drug development and molecular sciences, appreciating the scope and limitations of the adiabatic principle is critical. While it reliably describes ground-state chemistry, understanding photochemical processes, energy transfer, and the behavior of molecules in confined electromagnetic fields requires a view that transcends the BO approximation, embracing the rich, coupled quantum dynamics of electrons and nuclei.

From Theory to Practice: Computational Applications in Molecular Science and Drug Design

Ab initio quantum chemistry methods, which compute molecular properties from first principles using only physical constants and fundamental quantum mechanics, represent the gold standard for predictive computational chemistry. The practical application of these methods is fundamentally dependent on the Born-Oppenheimer (BO) approximation, which separates nuclear and electronic motions. This technical guide examines the foundational role of the BO approximation in enabling computationally feasible ab initio calculations, details the methodological hierarchy of contemporary quantum chemistry approaches, and provides practical protocols for researchers investigating molecular systems. Within the broader context of molecular systems research, we demonstrate how this theoretical framework underpins everything from drug discovery to materials science by allowing accurate prediction of molecular structure, reactivity, and properties.

The Born-Oppenheimer approximation, first proposed by J. Robert Oppenheimer and his adviser Max Born in 1927, addresses a fundamental challenge in molecular quantum mechanics: the coupled motion of electrons and atomic nuclei [1] [2]. In any molecular system, all particles—electrons and nuclei—interact through Coulomb forces, creating an intractable many-body problem. The BO approximation recognizes the significant mass disparity between these components; even a single proton is approximately 1800 times more massive than an electron [2] [12]. This mass difference translates to vastly different timescales of motion—electrons effectively instantaneously adjust to nuclear positions, while nuclei experience an averaged electronic potential [1] [28].

This separation enables the decoupling of the molecular Schrödinger equation into simpler electronic and nuclear components. For a molecule with N electrons and M nuclei, the exact non-relativistic Hamiltonian H is:

Where T_n and T_e are nuclear and electronic kinetic energy operators, and V_ne, V_ee, and V_nn represent nucleus-electron attraction, electron-electron repulsion, and nucleus-nucleus repulsion, respectively [1] [12]. The BO approximation allows solving the electronic Schrödinger equation at fixed nuclear configurations:

Where H_e = T_e + V_ne + V_ee + V_nn, χ(r;R) is the electronic wavefunction depending on electron coordinates r with parametric dependence on nuclear coordinates R, and E_e(R) is the potential energy surface for nuclear motion [1]. This separation reduces a coupled (3N+3M)-dimensional problem to a tractable 3N-dimensional electronic problem at each nuclear configuration, followed by a 3M-dimensional nuclear problem [1].

The Computational Framework of Ab Initio Methods

Methodological Hierarchy in Electronic Structure Theory

Ab initio (Latin for "from the beginning") methods compute molecular properties using only quantum mechanical principles without empirical parameters [29] [30]. These methods form a hierarchical framework where computational cost increases with accuracy, allowing researchers to select appropriate methods based on their specific precision requirements and available computational resources.

Table 1: Hierarchy of Ab Initio Quantum Chemistry Methods

| Method Class | Key Theory | Computational Scaling | Key Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hartree-Fock (HF) | Mean-field approximation | Nâ´ | Molecular orbitals, initial guess | Neglects electron correlation |

| Post-Hartree-Fock | ||||

| ┣ Møller-Plesset (MP2) | Perturbation theory | Nⵠ| Dispersion forces, non-covalent interactions | Fails for degenerate systems |

| ┣ Coupled Cluster (CCSD(T)) | Exponential ansatz | Nⷠ| "Gold standard" for small molecules | Prohibitive for large systems |

| â”— Configuration Interaction (CI) | Multideterminant expansion | N! | Excited states, bond breaking | Size consistency issues |

| Multi-Reference Methods | Complete Active Space (CASSCF) | Exponential | Bond breaking, diradicals | Active space selection challenging |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | Electron density functional | N³-Nⴠ| Large systems, transition metals | Functional selection empirical |

The Role of Basis Sets in Electronic Structure Calculations

In practical implementations, the molecular orbitals are expanded as linear combinations of atomic orbitals (LCAO) [29]. This requires selection of a basis set—a set of mathematical functions centered on atomic nuclei that describe the spatial distribution of electrons. Basis sets range from minimal (e.g., STO-3G) to extended with multiple polarization and diffuse functions (e.g., cc-pVQZ) [31]. The choice significantly impacts accuracy; for example, furan's bond lengths calculated with STO-3G show errors up to 1.4 pm compared to experimental values, while DZP MP2 calculations reduce errors to 0.3 pm [31].

Computational Protocols for Ab Initio Calculations

Standard Workflow for Molecular Property Prediction

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for ab initio calculations within the Born-Oppenheimer framework:

Protocol 1: Molecular Geometry Optimization and Frequency Analysis

Objective: Determine the equilibrium structure and verify it represents a true minimum on the potential energy surface.

- Initial Structure Setup: Build molecular structure using chemical intuition or molecular mechanics. For drug-like molecules, start with likely conformers.

- Method Selection: For initial screening, use DFT with functionals like B3LYP and basis sets like 6-31G(d). For higher accuracy, employ MP2 or CCSD(T) with correlation-consistent basis sets.

- Optimization Procedure:

- Set convergence criteria for energy (10â»â¶ Hartree), gradient (10â»â´ Hartree/Bohr), and displacement (10â»Â³ Bohr).

- Enable the Berny algorithm or similar optimizer.

- For flexible molecules, use relaxed potential energy surface scans to identify low-energy conformers.

- Frequency Calculation:

- Compute harmonic vibrational frequencies at the optimized geometry.

- Verify all frequencies are real (no imaginary frequencies) for a minimum.

- Apply appropriate scaling factors to account for anharmonicity and method limitations.

- Property Extraction: Calculate molecular properties (dipole moments, orbital energies, electrostatic potential) at the optimized geometry.

Protocol 2: Potential Energy Surface Scanning for Reaction Pathways

Objective: Map the energy landscape along a proposed reaction coordinate to locate transition states and intermediates.

- Reaction Coordinate Identification: Select a meaningful internal coordinate (bond length, angle, or dihedral) that describes the chemical transformation.

- Grid Definition: Define points along the coordinate with appropriate spacing (e.g., 0.1 Å for bond stretching, 10° for torsions).

- Constrained Optimization: At each point, optimize all other degrees of freedom while fixing the reaction coordinate.

- Transition State Location: Use the relaxed scan as initial guess for transition state optimization with algorithms like EF, QST2, or QST3.

- Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate (IRC): Follow the IRC path from the transition state to confirm it connects reactant and product basins.

- Energy Refinement: Perform high-level single-point energy calculations on stationary points to improve energetic predictions.

Quantitative Assessment of Computational Scaling

The computational cost of ab initio methods exhibits different scaling behavior with system size, critically influencing method selection for different applications.

Table 2: Computational Scaling and Resource Requirements for Ab Initio Methods

| Method | Formal Scaling | Practical System Size | Memory Requirements | Key Applications in Drug Discovery |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HF/DFT | N³-Nⴠ| Hundreds of atoms | Moderate | Conformational analysis, property prediction |

| MP2 | Nâµ | Tens of atoms | High | Non-covalent interactions, dispersion forces |

| CCSD(T) | Nâ· | Small molecules (<20 atoms) | Very high | Benchmarking, reaction energies |

| Local CCSD(T) | ~N | Medium-sized molecules | High | Accurate energies for drug-sized molecules |

| CASSCF | Exponential | Very small active spaces | Very high | Photochemical reactions, diradicals |

Advanced Applications and Specialized Protocols

Protocol 3: NMR Chemical Shift Prediction for Structure Validation

Objective: Calculate NMR chemical shifts to validate molecular structure against experimental data.

- Geometry Optimization: Optimize molecular structure at DFT level (B3LYP/6-31G(d) or similar).

- Magnetic Property Calculation: Compute NMR shielding tensors using gauge-including atomic orbitals (GIAO) method at the same or higher theory level.

- Reference Compound: Calculate shielding for reference compound (e.g., TMS for ¹H/¹³C) at identical theory level.

- Chemical Shift Derivation: δcalc = σref - σ_calc

- Statistical Validation: Compare calculated and experimental shifts using linear regression (R² > 0.95 typically indicates good agreement).

This approach has proven particularly valuable for characterizing enzyme-ligand interactions, where chemical shift changes upon binding reveal specific active site contacts [32]. For example, in studies of purine nucleoside phosphorylase (PNP), a target for anticancer agents, ab initio chemical shift calculations revealed specific hydrogen-bonding interactions between hypoxanthine and enzyme residues Glu201 and Asn243 [32].

Protocol 4: Beyond Born-Oppenheimer: Non-Adiabatic Dynamics

Objective: Simulate processes where electron-nuclear coupling cannot be neglected, such as photochemical reactions or conical intersections.