The Schrödinger Equation in Quantum Chemistry: From Fundamental Theory to Drug Discovery Applications

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the Schrödinger equation's central role in modern quantum chemistry, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

The Schrödinger Equation in Quantum Chemistry: From Fundamental Theory to Drug Discovery Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the Schrödinger equation's central role in modern quantum chemistry, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers the equation's foundational principles, from time-dependent and time-independent forms to the physical meaning of the wave function. The review systematically details core approximation methodologies like Hartree-Fock, post-Hartree-Fock, and Density Functional Theory, alongside emerging machine learning strategies. It addresses critical computational challenges and optimization techniques for tackling the many-body problem and highlights validation protocols and comparative analyses of method accuracy. The synthesis offers a practical guide for selecting computational methods and discusses future implications for accurate molecular modeling in biomedical research.

The Quantum Cornerstone: Understanding the Schrödinger Equation's Core Principles

The Core Foundation: The Wave Function

The foundational postulate of quantum mechanics states that the state of a quantum-mechanical system is completely specified by a wave function, typically denoted as Ψ (psi) [1]. This wave function depends on the coordinates of all the particles in the system and time. Unlike classical mechanics, where position and momentum can be precisely determined, the quantum description is inherently probabilistic [2].

The physical interpretation of the wave function, as defined by the Born Rule, is that its squared magnitude, |Ψ(r, t)|², represents a probability density [3] [1]. For a single particle, the probability of finding it within an infinitesimal volume element dV located at position r and at time t is given by |Ψ(r, t)|²dV [1]. This probabilistic interpretation is a radical departure from classical physics and has profound implications for predicting the behavior of microscopic systems.

For the probability interpretation to be consistent, the wave function must be well-behaved; it must be single-valued, continuous, and its first derivative must also be continuous [2] [1]. Furthermore, the wave function must be normalized, meaning the total probability of finding the particle somewhere in all space must equal unity [3]. The normalization condition is expressed mathematically as: [ \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} |\Psi(\mathbf{r}, t)|^2 d\tau = 1 ]

Table 1: Key Properties of the Wave Function

| Property | Mathematical Expression | Physical Significance | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Probabilistic Interpretation | ( P = | \Psi(\mathbf{r}, t) | ^2 d\tau ) | Probability of finding a particle in a volume element ( d\tau ) [1]. |

| Normalization | ( \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} | \Psi(\mathbf{r}, t) | ^2 d\tau = 1 ) | Ensures the total probability of finding the particle somewhere is 100% [3]. |

| Single-Valuedness | One value of ( \Psi ) per point in space | Guarantees a unique probability density at every location [1]. | ||

| Continuity | ( \Psi ) and ( \frac{\partial \Psi}{\partial x} ) are continuous | Required for well-defined solutions to the Schrödinger equation [1]. |

The Complete Framework: Corollary Postulates

While the first postulate introduces the wave function, the full predictive power of quantum mechanics is realized through several other fundamental postulates that complete the theoretical framework [3] [1].

Postulate 2: Physical Observables and Operators Every physical observable in classical mechanics (e.g., position, momentum, energy) corresponds to a linear and Hermitian operator in quantum mechanics [1]. For example, the operator for energy is the Hamiltonian operator, ( \hat{H} ), which is central to the Schrödinger equation [4].

Postulate 3: Measurement and Eigenvalues The only possible result of a measurement of a physical observable is one of the eigenvalues of the corresponding operator [1]. If an operator ( \hat{A} ) acts on a wave function ( \phi ) and yields a scalar multiple of itself (( \hat{A}\phi = a\phi )), then ( \phi ) is an eigenfunction of ( \hat{A} ) and ( a ) is the corresponding eigenvalue, representing a definite value that can be observed experimentally.

Postulate 4: Expectation Values For a system in a state described by a normalized wave function ( \Psi ), the average or expectation value of an observable corresponding to operator ( \hat{A} ) is given by [1]: [ \langle a \rangle = \int \Psi^{*} \hat{A} \Psi d\tau ] This provides the statistical mean of the measurement outcomes if the experiment is repeated many times on identically prepared systems.

Postulate 5: Time Evolution The wave function of a system evolves in time according to the time-dependent Schrödinger equation [3] [1]: [ \hat{H} \Psi(\mathbf{r}, t) = i \hbar \frac{\partial}{\partial t} \Psi(\mathbf{r}, t) ] This postulate governs the deterministic evolution of the quantum state when it is not being measured.

Table 2: The Postulates of Quantum Mechanics

| Postulate | Core Principle | Key Mathematical Expression | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The State Postulate | A system's state is described by a wave function ( \Psi ) [1]. | ( P = | \Psi | ^2 d\tau ) |

| The Observable Postulate | Physical observables are represented by operators [1]. | ( \hat{x} = x ), ( \hat{p}_x = -i\hbar\frac{\partial}{\partial x} ), ( \hat{H} = \hat{K} + \hat{V} ) | ||

| The Measurement Postulate | Measurement yields eigenvalues of the operator [1]. | ( \hat{A}\phin = an\phi_n ) | ||

| The Expectation Value Postulate | The average outcome of many measurements is the expectation value [1]. | ( \langle a \rangle = \int \Psi^{*} \hat{A} \Psi d\tau ) | ||

| The Dynamics Postulate | Time evolution is governed by the Schrödinger equation [1]. | ( \hat{H} \Psi = i \hbar \frac{\partial \Psi}{\partial t} ) |

The Schrödinger Equation: The Dynamical Heart

The time-dependent Schrödinger equation (TDSE) is the non-relativistic equation of motion for quantum systems, directly implementing the fifth postulate [2] [1]. For many practical applications, particularly in quantum chemistry where the goal is often to find stable energy states of molecules, the time-independent Schrödinger equation (TISE) is used [2] [4]. The TISE is an eigenvalue equation derived from the TDSE for cases where the potential energy is independent of time: [ \hat{H} \psi(\mathbf{r}) = E \psi(\mathbf{r}) ] Here, ( \psi(\mathbf{r}) ) is the time-independent wave function, and ( E ) is the total energy of the system in a stationary state [4]. Solving this equation for molecules is the primary task of computational quantum chemistry.

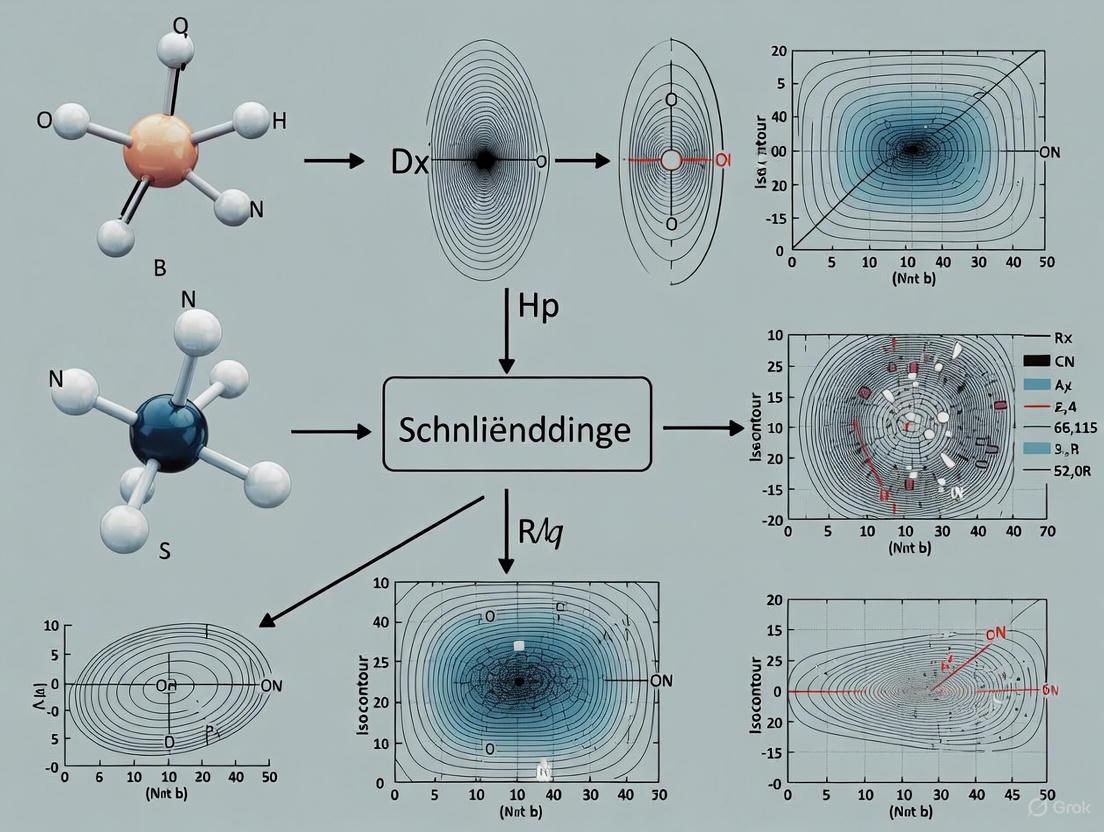

Diagram 1: Workflow for solving the time-independent Schrödinger equation.

Approximation Strategies for the Many-Body Problem

For any system with more than one electron, the many-body Schrödinger equation becomes exponentially complex and cannot be solved exactly [5] [6]. This fundamental intractability has driven the development of numerous approximation strategies, which form the cornerstone of modern quantum chemistry [5].

The Central Challenge: The Coulombic interactions between electrons create a complex correlated motion. Solving the Schrödinger equation for a molecule with N electrons means dealing with a wave function Ψ(râ‚, râ‚‚, ..., râ‚™) in 3N dimensions, a computational task that quickly becomes impossible for all but the smallest systems [5] [7].

Table 3: Major Approximation Methods in Quantum Chemistry

| Method | Fundamental Approach | Key Function/Quantity | Accuracy vs. Cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hartree-Fock (HF) | Mean-field approximation; each electron moves in an average field of others [5]. | Approximate Wave Function | Low cost, low to moderate accuracy [5]. |

| Post-Hartree-Fock Methods | Adds electron correlation on top of HF (e.g., Configuration Interaction, Coupled-Cluster) [5]. | Correlated Wave Function | High cost, high accuracy [5]. |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | Uses electron density instead of wave function to compute energy [5] [6]. | Electron Density | Moderate cost, good accuracy; widely used [5] [7]. |

| Quantum Monte Carlo (QMC) | Uses stochastic (random) sampling to solve the Schrödinger equation [5]. | Wave Function (sampled) | Very high cost, very high accuracy [5]. |

| Semi-Empirical Methods | Uses experimental data to simplify and parameterize the Hamiltonian [6]. | Parameterized Hamiltonian | Low cost, lower accuracy; speed is key [6]. |

Advanced Computational Protocols and The Scientist's Toolkit

The relentless push for more accurate and efficient solvers for the Schrödinger equation continues to define cutting-edge research in quantum chemistry. One of the most promising recent developments is the integration of deep learning to model the electronic wave function directly [7].

Protocol: Deep Neural Network Solution for the Schrödinger Equation

A groundbreaking approach developed by researchers at Freie Universität Berlin involves using a deep neural network, named PauliNet, to represent the wave function of electrons [7].

- Objective: To approximate the exact wave function of a molecular system with an unprecedented combination of accuracy and computational efficiency, overcoming the limitations of traditional methods [7].

- Network Architecture: A deep neural network is designed to learn the complex patterns of how electrons are distributed around nuclei. The inputs to the network are the coordinates of the electrons and nuclei [7].

- Physical Constraints: A critical innovation is building fundamental physical laws directly into the AI's architecture:

- Pauli Exclusion Principle: The network architecture is hard-coded to be antisymmetric. This means the wave function changes sign when the coordinates of any two electrons are exchanged, ensuring that no two electrons can be in the same quantum state [7].

- Other Physical Properties: Other known physical constraints, such as the functional form of the electron-nucleus and electron-electron interactions (Coulomb cusps), are also built in. This "physics-informed" approach is essential for making meaningful scientific predictions and reduces the amount of data needed for training [7].

- Training and Execution: The network is trained using a Quantum Monte Carlo framework, where the energy expectation value is computed based on the network's wave function. The network parameters are then optimized to minimize this energy, effectively solving the Schrödinger equation [7].

Diagram 2: Architecture of a deep-learning approach (PauliNet) for solving the Schrödinger equation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 4: Key Computational and Experimental Tools in Quantum Chemistry Research

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Role in Research |

|---|---|

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Clusters | Provides the massive computational power required for ab initio and DFT calculations on large molecular systems. |

| Quantum Chemistry Software (e.g., Gaussian, GAMESS, PySCF) | Implements complex algorithms for solving the Schrödinger equation and calculating molecular properties. |

| Ab Initio Methods | Provides solutions from first principles (quantum mechanics) without empirical parameters, serving as a benchmark for accuracy [6]. |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | A practical and efficient workhorse for calculating electronic structures in drug-sized molecules and materials [5] [7]. |

| Spectroscopic Data (NMR, IR, UV-Vis) | Experimental data from techniques like NMR and IR spectroscopy used to validate the accuracy of theoretical predictions [6]. |

| Manganese tungsten oxide (MnWO4) | Manganese tungsten oxide (MnWO4), CAS:13918-22-4, MF:MnO4W, MW:302.8 g/mol |

| p-Methyl-cinnamoyl Azide | p-Methyl-cinnamoyl Azide, CAS:24186-38-7, MF:C₁₀H₉N₃O, MW:187.2 g/mol |

The fundamental postulate of quantum mechanics—that a wave function completely describes a quantum system—is the bedrock upon which our modern understanding of the molecular world is built. This postulate, together with the Schrödinger equation which gives it dynamical life, provides the formal framework for all of quantum chemistry. While the exact solution of the many-body Schrödinger equation remains computationally intractable, the ingenious approximation methods developed—from Hartree-Fock and Density Functional Theory to the emerging deep neural network techniques—demonstrate the power of this foundational theory to drive scientific progress. By enabling the accurate prediction of molecular structure, reactivity, and properties, these quantum mechanical principles continue to be indispensable tools for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to solve complex problems at the atomic scale.

The Schrödinger equation stands as the cornerstone of quantum mechanics, providing the fundamental framework for understanding atomic and molecular behavior. Its two primary formulations—the time-dependent (TDSE) and time-independent (TISE) Schrödinger equations—serve complementary roles in computational chemistry and drug discovery. While the TDSE captures the full dynamical evolution of quantum systems, the TISE provides access to stationary states and energy levels that are essential for predicting molecular structure and reactivity. This whitepaper examines the mathematical foundations, computational methodologies, and practical applications of both equations, highlighting their critical role in modern pharmaceutical research. By deconstructing these equations and their implementations, we illuminate how quantum mechanical principles enable researchers to predict drug-target interactions, optimize therapeutic candidates, and accelerate the development of novel medicines.

Theoretical Foundations of the Schrödinger Equation

Historical Context and Fundamental Principles

The Schrödinger equation was postulated by Erwin Schrödinger in 1926, forming the basis for work that earned him the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1933 [8]. This equation represents the quantum counterpart to Newton's second law in classical mechanics, providing a mathematical prediction of how a physical system will evolve over time given known initial conditions [8]. Quantum mechanics describes the behavior of matter and energy at atomic and subatomic scales, where classical physics no longer applies and phenomena such as wave-particle duality and quantum uncertainty govern system behavior [9]. The Schrödinger equation provides a mathematical framework for understanding these non-intuitive quantum phenomena, enabling predictions about quantum system behavior and the probabilities of different measurement outcomes [9].

The fundamental object in quantum mechanics is the wave function, denoted as Ψ, which contains all information about a quantum system [10]. The wave function is a complex-valued function of position and time that must be continuous, single-valued, and square-integrable [10]. The physical interpretation of the wave function arises from its probability density, given by |Ψ|², which defines the likelihood of finding a particle in a specific region of space [10] [9]. This probabilistic interpretation represents a fundamental departure from classical deterministic physics and has profound implications for understanding molecular interactions at the atomic level [11].

The Hamiltonian Operator

Central to both forms of the Schrödinger equation is the Hamiltonian operator (Ĥ), which represents the total energy of the system [10] [9]. The Hamiltonian consists of kinetic energy (T̂) and potential energy (V̂) operators:

Ĥ = T̂ + V̂

For a single particle in one dimension, the Hamiltonian takes the form: Ĥ = -Ⅎ/2m · ∂²/∂x² + V(x)

where â„ is the reduced Planck constant, m is the particle mass, and V(x) is the potential energy function [10] [8]. The Hamiltonian operator acts on the wave function to extract information about the system's energy properties, forming the foundation for understanding molecular structure and reactivity in chemical systems.

Mathematical Deconstruction of the Two Forms

Time-Dependent Schrödinger Equation (TDSE)

The time-dependent Schrödinger equation describes the evolution of quantum states over time and accounts for systems with time-dependent potentials [10]. Its general form is:

i℠∂Ψ/∂t = ĤΨ

where i is the imaginary unit, ℠is the reduced Planck constant, Ψ is the wave function, and Ĥ is the Hamiltonian operator [10] [8] [12]. This partial differential equation governs how the wave function changes with time, providing a complete description of quantum system dynamics [13]. The presence of the imaginary unit i in the equation indicates that solutions generally involve complex-valued wave functions, with the time evolution representing a unitary process that preserves the normalization of the wave function [8].

The TDSE is particularly important for studying dynamic quantum processes, such as electron transitions in atoms, molecular vibrations, and chemical reactions [10] [12]. In pharmaceutical research, the TDSE enables the simulation of time-dependent phenomena like molecular collisions, energy transfer processes, and the response of molecular systems to external time-varying perturbations such as laser fields [12] [11].

Time-Independent Schrödinger Equation (TISE)

The time-independent Schrödinger equation applies to systems with time-independent Hamiltonians and is derived from the TDSE when the potential energy is constant in time [10] [14]. Its general form is:

Ĥψ = Eψ

where ψ represents the spatial part of the wave function, and E is the energy eigenvalue [10] [8]. This equation is an eigenvalue equation where the Hamiltonian operator acts on the wave function to yield the same wave function multiplied by its corresponding energy value [14].

Solutions to the TISE represent stationary states with definite energy values [10]. These stationary states are fundamental to understanding quantum systems, particularly bound states like electrons in atoms or molecules [10] [14]. For a system in a stationary state, the probability density |ψ|² remains constant in time, and the wave function evolves only by a phase factor:

Ψ(x,t) = ψ(x)e^(-iEt/â„)

This property makes stationary states particularly valuable for determining the allowed energy levels of quantum systems and their corresponding wave functions [14].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Time-Dependent and Time-Independent Schrödinger Equations

| Feature | Time-Dependent Schrödinger Equation | Time-Independent Schrödinger Equation |

|---|---|---|

| Mathematical Form | iâ„∂Ψ/∂t = ĤΨ [10] [8] | Ĥψ = Eψ [10] [8] |

| Time Dependence | Explicit time dependence [14] | No explicit time dependence [14] |

| Solutions Represent | Evolution of quantum states over time [10] | Stationary states with definite energy [10] |

| Probability Density | Can change with time [14] | Constant in time for stationary states [14] |

| Primary Applications | Dynamic processes, time-dependent perturbations [10] [12] | Energy levels, molecular structure [10] |

| Computational Complexity | Generally higher due to time evolution [15] [16] | Lower, eigenvalue problem [15] |

| Mathematical Nature | Partial differential equation [13] | Eigenvalue equation [14] |

Relationship Between TDSE and TISE

The relationship between the time-dependent and time-independent forms is established through the separation of variables technique [10] [13]. This method assumes that the wave function can be separated into spatial and temporal parts:

Ψ(x,t) = ψ(x)φ(t)

Substituting this into the TDSE allows separation into two ordinary differential equations: one for the spatial part ψ(x) that corresponds to the TISE, and one for the temporal part φ(t) that has the solution φ(t) = e^(-iEt/â„) [13] [14]. This separation demonstrates that the TISE emerges from the TDSE when the Hamiltonian is time-independent, with the stationary states of the TISE serving as building blocks for more general solutions to the TDSE [14].

The general solution to the TDSE can be expressed as a linear combination of these separated solutions:

Ψ(x,t) = Σₙ cₙψₙ(x)e^(-iEâ‚™t/â„)

where the coefficients câ‚™ are determined by initial conditions [10]. This superposition principle allows for the construction of complex quantum states from simpler stationary states and is fundamental to understanding phenomena such as quantum coherence and interference [10].

Computational Methodologies and Challenges

Solving the Time-Independent Schrödinger Equation

Computational approaches to solving the TISE in quantum chemistry typically begin with the Born-Oppenheimer approximation, which separates nuclear and electronic motion by treating nuclei as stationary relative to electrons [15]. This simplification reduces the problem to finding the lowest energy arrangement of electrons for a given nuclear configuration [15].

The Hartree-Fock method represents a foundational approach, which neglects specific electron-electron interactions and models each electron as interacting with the "mean field" exerted by other electrons [15]. This leads to an iterative self-consistent field (SCF) approach that typically converges in 10-30 cycles [15]. To represent molecular orbitals, computational chemists typically employ basis sets—collections of pre-optimized atom-centered Gaussian spherical harmonics used to construct molecular orbitals through linear combinations of atomic orbitals (LCAO) [15].

More advanced post-Hartree-Fock methods account for electron correlation through approaches like Møller-Plesset perturbation theory (MP2) and coupled-cluster theory, offering improved accuracy at significantly higher computational cost [15]. Density-functional theory (DFT) has emerged as one of the most widely used quantum chemical methods, incorporating electron correlation through an exchange-correlation potential while maintaining computational efficiency comparable to Hartree-Fock [15].

Solving the Time-Dependent Schrödinger Equation

Solving the TDSE presents distinct computational challenges, particularly for many-body systems [16]. Numerical approaches generally fall into two categories: direct real-space discretization methods and quantum-chemistry methods based on structured wavefunction ansätze [16].

Direct methods like the Crank-Nicolson scheme and split-operator techniques evolve the wavefunction on a spatial grid through stepwise integration [16]. While systematically improvable and avoiding physical-model approximations, these methods become intractable for many-fermion systems due to the curse of dimensionality [16].

Quantum-chemistry methods include:

- Time-Dependent Hartree-Fock (TDHF): Applies mean-field approximation to reduce the many-body problem to an effective single-particle framework [16]

- Real-Time Time-Dependent Density Functional Theory (RT-TDDFT): Extends DFT to time-dependent scenarios [16]

- Multiconfiguration TDHF (MCTDHF): Employs multiple configurations to capture electron correlation [16]

- Time-Dependent Configuration Interaction (TDCI): Utilizes excited configurations to model system evolution [16]

- Time-Dependent Coupled-Cluster (TDCC): Provides high accuracy with steep computational scaling [16]

These methods ultimately rely on step-by-step time propagation using numerical integrators, leading to accumulation of numerical errors in long-time simulations [16].

Table 2: Computational Methods for Solving Schrödinger Equations in Quantum Chemistry

| Method | Applicable Equation | Computational Scaling | Key Features | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hartree-Fock (HF) [15] | Time-Independent | O(Nâ´) [15] | Mean-field approximation, self-consistent field | Neglects electron correlation |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) [15] | Time-Independent | O(N³) [15] | Exchange-correlation functional, good accuracy/efficiency tradeoff | Functional dependence, challenges with strongly correlated systems |

| Coupled-Cluster (CC) [15] | Time-Independent | O(Nâ¶) and higher [15] | High accuracy for electron correlation | High computational cost |

| Time-Dependent DFT (TDDFT) [16] | Time-Dependent | O(N³) to O(Nâ´) | Extends DFT to excited states and dynamics | Challenges with charge-transfer states and strong correlations |

| Time-Dependent CI (TDCI) [16] | Time-Dependent | O(Nâ¶) per time step [16] | Configurational expansion for dynamics | Exponential scaling with system size |

| Neural Network Approaches [16] | Both | Variable | Global spacetime optimization, fermionic antisymmetry | Training data requirements, convergence challenges |

Emerging Computational Approaches

Recent advances in machine learning have introduced novel approaches for solving both time-independent and time-dependent Schrödinger equations [16]. Neural-network quantum Monte Carlo (NN-QMC) methods have demonstrated impressive performance for the TISE, particularly in modeling ground-state wavefunctions of fermionic systems with physical constraints like permutation antisymmetry [16].

For the TDSE, approaches like the Fermionic Antisymmetric Spatio-Temporal Network treat time as an explicit input alongside spatial coordinates, enabling unified spatiotemporal representation of complex, antisymmetric wavefunctions for fermionic systems [16]. This method formulates the TDSE as a global optimization problem, avoiding step-by-step propagation and supporting highly parallelizable training [16]. Such global optimization approaches mitigate the error accumulation inherent in sequential time evolution methods, though the causal structure of time-dependent equations remains a fundamental constraint [16].

Diagram 1: Computational Framework for Schrödinger Equations

Applications in Drug Discovery and Pharmaceutical Research

Molecular Structure and Property Prediction

The time-independent Schrödinger equation provides the foundation for predicting molecular structure and properties essential to pharmaceutical development [15] [11]. By solving the TISE for molecular systems, computational chemists can determine:

- Molecular geometries: Equilibrium structures and conformational landscapes [15]

- Electronic properties: Charge distributions, molecular orbitals, and dipole moments [11]

- Spectroscopic parameters: NMR chemical shifts, vibrational frequencies, and electronic excitation energies [15]

- Thermodynamic properties: Binding energies, reaction energies, and activation barriers [15] [11]

These predictions enable researchers to understand and optimize key pharmaceutical properties including solubility, permeability, and metabolic stability before synthesizing compounds, significantly accelerating the drug discovery process [15] [17].

Drug-Target Interactions and Binding Energy Calculations

Quantum chemical methods based on the Schrödinger equation provide detailed insights into drug-target interactions at the atomic level [11]. The TISE enables calculation of electron distributions, molecular orbitals, and energy states critical for understanding intermolecular interactions [11]. For example, hydrogen bonding—crucial in protein folding and drug-target interactions—depends critically on quantum mechanical electron density distribution that cannot be accurately predicted using classical approaches alone [11].

In the case of the antibiotic vancomycin, binding to bacterial cell wall components depends on five hydrogen bonds whose strength emerges from quantum effects in electron density distribution [11]. Similarly, π-stacking interactions that stabilize drug-aromatic amino acid interactions in histone deacetylase inhibitors depend on quantum mechanical electron delocalization [11]. These quantum-derived interactions directly impact binding affinity and specificity, essential parameters in drug optimization [11].

Quantum Effects in Biological Systems

Quantum mechanical effects such as tunneling, superposition, and entanglement fundamentally influence molecular behavior in biological systems [11]. While these effects originate at atomic and subatomic scales, they propagate upward to influence molecular behavior in pharmacologically relevant contexts [11].

Quantum tunneling enables reactions to occur despite classical energy barriers, with significant implications for drug action and metabolism [11]. For example, soybean lipoxygenase catalyzes hydrogen transfer with a kinetic isotope effect of approximately 80, far exceeding the maximum value of ~7 predicted by classical transition state theory, indicating hydrogen tunnels through the energy barrier [11]. Lipoxygenase inhibitors engineered to disrupt optimal tunneling geometries can achieve greater potency than those designed solely on classical considerations [11].

In DNA, proton tunneling affects tautomerization rates between canonical and rare tautomeric forms of nucleobases, causing spontaneous mutations that occur approximately once per 10,000 to 100,000 base pairs [11]. Some DNA repair enzyme inhibitors developed as anticancer agents target processes that correct these quantum-induced mutations [11].

Multi-Scale Modeling in Pharmaceutical Development

The integration of quantum mechanics with molecular mechanics (QM/MM) enables multi-scale modeling approaches that balance accuracy and computational efficiency in drug discovery [15] [11]. In these hybrid schemes, the chemically active region (e.g., enzyme active site with bound ligand) is treated quantum mechanically, while the remainder of the system is modeled using molecular mechanics force fields [15].

This approach is particularly valuable for studying enzyme-catalyzed reactions and drug-receptor interactions where electronic structure changes fundamentally influence the process [11]. For instance, in the structure-based design of HIV protease inhibitors, a multi-scale approach demonstrates the quantum-classical interface, with quantum methods describing the electronic rearrangement during binding and classical methods capturing the conformational flexibility of the protein [11].

Table 3: Quantum Chemical Applications in Drug Discovery Pipeline

| Drug Discovery Stage | Quantum Chemical Application | Schrödinger Equation Form | Impact on Development |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target Identification | Protein-ligand interaction prediction [11] | Time-Independent | Prioritize targets with favorable binding pockets |

| Hit Identification | Virtual screening of compound libraries [17] | Time-Independent | Identify promising scaffolds from millions of candidates |

| Lead Optimization | Binding affinity calculations [11] [17] | Both | Rational design of higher potency compounds |

| ADMET Prediction | Solubility, permeability, metabolism prediction [15] [17] | Time-Independent | Optimize pharmacokinetic and safety properties |

| Reaction Mechanism Elucidation | Enzymatic catalysis, drug metabolism [11] | Both | Understand activation and detoxification pathways |

Current Research and Future Perspectives

Integration with Machine Learning Methods

The integration of quantum chemistry with machine learning represents a transformative development in computational drug discovery [17] [16]. Companies like Schrödinger employ physics-based first principles to generate training data for machine learning models that can rapidly predict molecular properties [17]. As explained by Schrödinger CEO Ramy Farid, "The calculations are slow, relatively speaking. It takes about a day to compute one property on one processor, approximately 12-24 hours. And to do drug discovery, we need to explore hundreds of millions—billions, actually—of molecules. Even if you had one million computers, you couldn't do that—and we don't have access to one million computers! So, we need this hack, if you will, to generate training sets, with physics that's pretty fast to generate a large enough amount of data to train a machine-learned model." [17]

This combined approach enables the exploration of vast chemical spaces while maintaining the accuracy of physics-based methods, dramatically accelerating the drug discovery process [17]. Machine learning models trained on quantum chemical data can predict properties of billions of molecules in seconds, overcoming the computational bottleneck of pure quantum mechanical calculations [17].

Advanced Dynamics Simulations

Recent advances in solving the time-dependent Schrödinger equation open new possibilities for simulating ultrafast dynamical processes in pharmaceutical research [12] [16]. Applications include:

- Ultrafast electronic dynamics: Modeling high-order harmonic generation and multiphoton ionization [16]

- Nonequilibrium phenomena: Studying light-induced phase transitions and transient transport under strong laser fields [16]

- Real-time electron transfer: Simulating charge migration in biological molecules [11] [16]

- Laser-driven molecular control: Designing optical control strategies for selective bond breaking or formation [12] [16]

Neural network approaches that treat time as an explicit input variable enable global optimization across spacetime domains, potentially overcoming limitations of stepwise propagation methods [16]. These advances create opportunities for simulating complex quantum dynamics in pharmacologically relevant systems with unprecedented accuracy and efficiency [16].

Quantum-Informed Drug Design

The ongoing integration of quantum mechanical principles into drug discovery workflows is creating a new paradigm of quantum-informed drug design [11] [17]. This approach leverages the fundamental understanding provided by the Schrödinger equation to guide therapeutic development at multiple levels:

Electronic structure-informed design focuses on optimizing electronic complementarity between drugs and their targets, moving beyond traditional shape-based approaches [11]. For example, Schrödinger's drug discovery platform has contributed to development programs including:

- TAK-279: A TYK2 inhibitor for psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis developed with Nimbus Therapeutics, now in Phase II trials [17]

- SGR-1505: A MALT1 inhibitor for B-cell lymphomas, currently in Phase I trials [17]

- SGR-2921: A CDC7 inhibitor for acute myeloid leukemia, entering Phase I studies [17]

- GSBR-1290: An oral GLP-1R agonist for type 2 diabetes and obesity developed with Structure Therapeutics [17]

Quantum dynamics-informed design accounts for nuclear quantum effects and tunneling in enzyme inhibition, enabling the optimization of reaction kinetics and residence times [11]. As demonstrated in lipoxygenase inhibitors, disrupting optimal tunneling geometries can enhance drug potency beyond what is achievable through classical design approaches [11].

Diagram 2: Quantum-Informed Drug Discovery Pipeline

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Quantum Chemistry Applications

| Tool/Category | Function | Examples/Alternatives |

|---|---|---|

| Electronic Structure Software | Solving TISE for molecular systems [15] | Gaussian, GAMESS, NWChem, Q-Chem, ORCA |

| Dynamics Simulation Packages | Solving TDSE for time-dependent phenomena [16] | Octopus, CHEMSHELLA, Dirac, SALMON |

| Basis Sets | Representing molecular orbitals [15] | Pople basis sets, Dunning's cc-pVXZ, Karlsruhe def2 series |

| Pseudopotentials | Representing core electrons [15] | Effective core potentials, pseudopotential libraries |

| Force Fields | Molecular mechanics for QM/MM [15] | AMBER, CHARMM, OPLS-AA |

| Neural Network Frameworks | Machine learning approaches to Schrödinger equations [16] | FermiNet, PauliNet, DeepWave, SchNet |

| Visualization Software | Analyzing molecular orbitals and electron density [15] | GaussView, Avogadro, VMD, Chimera |

| High-Performance Computing | Computational resources for quantum chemistry [15] [17] | CPU clusters, GPU acceleration, cloud computing |

The Schrödinger equation in its time-dependent and time-independent forms provides the fundamental theoretical framework underlying modern computational chemistry and drug discovery. While the time-independent form enables prediction of molecular structure, properties, and stationary states, the time-dependent form captures the dynamical evolution of quantum systems essential for understanding reactivity and time-dependent phenomena. The integration of these complementary approaches, enhanced by emerging machine learning methods and computational advances, continues to transform pharmaceutical research by enabling increasingly accurate predictions of molecular behavior. As computational power and methodological sophistication advance, quantum chemical approaches rooted in the Schrödinger equation will play an increasingly central role in accelerating drug discovery and development, ultimately contributing to more efficient creation of novel therapeutics for human health.

The Schrödinger equation stands as the cornerstone of quantum chemistry, providing the fundamental mathematical framework for describing the behavior of electrons in atoms and molecules. The solutions to this equation are wavefunctions (ψ), which encode all information about a quantum system. The physical interpretation of these wavefunctions, and particularly their squared modulus (|ψ|²), is what bridges abstract quantum theory with concrete, predictive chemistry. This interpretation allows researchers to predict molecular structures, reaction pathways, and electronic properties with remarkable accuracy. For professionals in drug development and materials science, understanding these concepts is not merely academic; it is essential for rational design of novel compounds, interpretation of spectroscopic data, and prediction of biochemical activity. This guide examines the physical interpretation of the wavefunction and its probability density, detailing the theoretical foundations, computational methodologies for their determination, and their critical applications in modern chemical research.

The Wavefunction (ψ) and the Born Interpretation

The wavefunction, ψ, is a complex-valued function of the spatial coordinates of a system's particles and time [18] [19]. For a single particle, ψ(r, t) describes its quantum state completely. However, the wavefunction itself does not represent a direct physical observable [20].

The breakthrough in physical interpretation came from Max Born, who postulated that the square of the absolute value of the wavefunction, |ψ(r, t)|², is proportional to the probability density of finding the particle at a point in space r and time t [18] [21] [22]. For a single-particle system, the probability P of finding the particle in a small volume element dτ is given by: P(r, t) dτ = |ψ(r, t)|² dτ = ψ(r, t) ψ(r, t) *dτ [18].

This Born interpretation fundamentally shifted the description of particles from deterministic trajectories to probabilistic distributions, resolving paradoxes in early quantum theory and establishing the foundational principle of quantum mechanics [18] [22].

Probability Density (|ψ|²) and its Properties

The probability density, |ψ|², is always a real, non-negative number [21] [19]. This is crucial for its role as a probability measure. To find the probability that a particle is located within a specific region of space (e.g., between points a and b in one dimension), one integrates the probability density over that volume [18] [21]:

- One Dimension: ( P(x \in [a,b]) = \int_{a}^{b} |\psi (x)|^2 dx ) [18]

- Three Dimensions: ( P \in V = \iiint_{V} |\psi (\vec{r})|^2 d\tau ) [18]

The volume element dτ depends on the coordinate system (e.g., dx dy dz in Cartesian coordinates, r² sinφ dr dθ dφ in spherical coordinates) [18].

For this probabilistic interpretation to be physically meaningful, the wavefunction must adhere to several strict mathematical conditions, often called the requirements for a "well-behaved" wavefunction [18] [19]:

- Normalization: The total probability of finding the particle somewhere in the entire universe must be exactly 1. This requires that ( \iiint_{\text{all space}} |\psi (\vec{r})|^2 d\tau = 1 ) [21] [19]. A wavefunction can be multiplied by a constant phase factor e^(iθ) without changing the physical state, but its magnitude must be scaled to satisfy this condition.

- Single-Valued: At any point in space, ψ must have one and only one value. A multi-valued function would lead to ambiguous predictions for probabilities [18] [19].

- Continuous: The wavefunction itself, and its first spatial derivative, must be continuous everywhere. This is required for solving the Schrödinger equation and ensures physically reasonable, smooth probability distributions [18] [19].

- Finite: The wavefunction must not diverge to infinity in any region of space, as this would imply an infinite probability density, which is unphysical [18].

The Schrödinger Equation: Generator of Wavefunctions

The wavefunction for a given system is not arbitrary; it is determined by solving the Schrödinger equation, which incorporates the potential energy environment of the particles [19] [22]. The time-independent Schrödinger equation for a stationary state is an eigenvalue equation: ( \hat{H} \psi = E \psi ) [22] Here, (\hat{H}) is the Hamiltonian operator, which represents the total energy operator (sum of kinetic and potential energy), ψ is the wavefunction of the stationary state, and E is the exact energy eigenvalue corresponding to that state [22]. Solving this equation for molecules, subject to the boundary conditions of the system, yields the allowed wavefunctions and their associated energies [20] [22].

Table 1: Key Properties and Interpretations of the Wavefunction and Probability Density

| Concept | Mathematical Representation | Physical Interpretation | Key Constraints | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wavefunction (ψ) | Complex function: ψ(r, t) | Probability amplitude; contains all quantum information about the system [19]. | Must be single-valued, continuous, and finite [18] [19]. | ||

| Probability Density ( | ψ | ²) | Real function: |ψ(r, t)|² = ψ*(r, t)ψ(r, t) [18] | Probability per unit volume of finding a particle at r at time t [18] [21]. | Must be non-negative and normalizable [21] [19]. |

| Normalization | ( \iiint_{\text{all space}} |\psi|^2 d\tau = 1 ) [21] | Ensures the total probability of finding the particle is 100% [21]. | Applied by scaling the wavefunction with a constant [21]. |

Computational Methodologies for Determining Wavefunctions

Theoretical Framework of Wavefunction-Based Methods

In practice, the many-electron Schrödinger equation for molecules cannot be solved exactly. Quantum chemistry has developed a hierarchy of Wavefunction Theory (WFT) methods to approximate the true wavefunction and its energy [23]. These methods are broadly classified by the nature of their reference state:

- Single-Reference Methods: These start from a single Slater determinant (a single electronic configuration), often the Hartree-Fock (HF) solution. The Coupled-Cluster (CC) method, particularly CCSD(T)—which includes single, double, and a perturbative estimate of triple excitations—is considered the "gold standard" for single-reference systems due to its high accuracy [23].

- Multireference Methods: For systems with significant "static correlation" (e.g., bond breaking, open-shell transition metal complexes), a single determinant is insufficient. Methods like CASSCF (Complete Active Space Self-Consistent Field) start from a linear combination of strategically chosen Slater determinants to describe near-degenerate electronic states [23]. The active space must be carefully selected, often including metal d orbitals and key ligand orbitals in transition metal chemistry [23].

A critical challenge in all WFT methods is the slow convergence of correlation energy with basis set size. Techniques like explicitly correlated (F12) methods and complete basis set (CBS) extrapolation are used to mitigate this, dramatically improving accuracy for a given computational cost [23].

Advanced and Emerging Computational Protocols

The high computational cost of accurate WFT methods, which often scales exponentially with system size, has driven the development of efficient composite protocols and novel computational paradigms.

Table 2: Advanced Computational Protocols in Wavefunction-Based Quantum Chemistry

| Method/Protocol | Core Approach | Primary Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Composite CCSD(T) Protocol [23] | Splits energy into core-valence CCSD(F12), relativistic/core-correlation, and (T) contributions, computed with optimized composite basis sets. | High-accuracy (1-3 kcal/mol) spin-state energetics in heme models and transition metal complexes. | Achieves near-CBS limit accuracy at reduced cost; designed for systems up to ~37 atoms. |

| Density Matrix Renormalization Group (DMRG) [24] | A tensor network method that efficiently handles strong correlation in large active spaces by optimizing the matrix product state (MPS) wavefunction ansatz. | Strongly correlated systems with large active spaces (e.g., polyenes, metal clusters). | More efficient than exact diagonalization for 1D-like correlations; cost scales with bond dimension χ. |

| Neural Network Quantum States (QiankunNet) [25] | Parameterizes the wavefunction with a Transformer neural network, optimized via variational Monte Carlo (VMC) with autoregressive sampling. | Exact solution of molecular systems (up to 30 spin orbitals) and very large active spaces (e.g., CAS(46e,26o)). | Combines expressivity of neural networks with efficient sampling; achieves >99.9% of FCI energy. |

The recent QiankunNet framework demonstrates how modern machine learning architectures are being applied to this fundamental problem. It uses a Transformer-based wavefunction ansatz to capture complex quantum correlations and employs an efficient Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) for autoregressive sampling, avoiding the bottlenecks of traditional Markov Chain Monte Carlo methods [25]. This has enabled the handling of previously intractable active spaces, such as in the Fenton reaction mechanism [25].

Table 3: Key "Research Reagent Solutions" in Computational Wavefunction Analysis

| Item / Software Tool | Function / Purpose | Typical Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Provides the massive computational power required for high-level ab initio calculations (CCSD(T), DMRG, CASSCF). | Essential for all production-level quantum chemical calculations on drug-sized molecules. |

| Quantum Chemistry Packages (e.g., PySCF, Molpro, CFOUR) | Implements the algorithms for solving the Schrödinger equation and computing molecular properties from wavefunctions. | Running HF, CC, CI, and CASSCF calculations; integral transformation; property evaluation. |

| SparQ Tool [24] | Efficiently computes quantum information theory observables (e.g., mutual information, entropy) on sparse post-HF wavefunctions. | Analyzing electron correlation and entanglement patterns in molecules to guide active space selection. |

| Gaussian-type Orbital Basis Sets | A set of basis functions used to expand the molecular orbitals, defining the flexibility of the electron distribution. | Pople-style (e.g., 6-31G) or correlation-consistent (e.g., cc-pVTZ) basis sets are selected based on the target accuracy. |

Visualization of the Quantum Chemistry Workflow

The process of moving from a molecular structure to a physically interpreted wavefunction involves a well-defined sequence of steps, which integrates the components discussed in the previous sections. The following diagram outlines this core computational workflow in quantum chemistry research.

Diagram 1: Computational Workflow in Wavefunction-Based Quantum Chemistry.

This workflow highlights the critical path from a molecular structure to chemical insight. The Wavefunction Theory (WFT) Calculation node is the computational core where methods like CCSD(T) or CASSCF are applied. The resulting wavefunction (ψ) is then used to compute the physical probability density (|ψ|²), which directly feeds into the calculation of observable properties and their final chemical interpretation.

Applications in Chemical Research and Drug Development

The ability to compute and interpret wavefunctions and electron probability densities is indispensable in modern chemical research. Key applications include:

- Predicting Molecular Interaction Sites: Electrostatic potential maps, derived from the total electron probability density, are used to identify nucleophilic and electrophilic sites on drug molecules, predicting how they will interact with biological targets [19]. This guides the optimization of binding affinity and selectivity.

- Modeling Transition Metal Complexes: In catalytic and enzymatic sites, the electron density distribution around transition metals (like Fe in heme) determines spin states, reactivity, and oxidation potentials. Multireference wavefunction methods (e.g., CASPT2) are essential for accurately modeling the complex electronic structure of these systems, as demonstrated in studies of the Fenton reaction and heme proteins [23] [25].

- Rationalizing Reaction Mechanisms: By computing wavefunctions and energies at different points along a reaction coordinate, quantum chemistry can reveal transition state structures, activation energies, and intermediate stability. The QiankunNet framework's application to the Fenton reaction mechanism showcases how advanced wavefunction methods can describe the complex electronic structure evolution during processes like Fe(II) to Fe(III) oxidation [25].

- Interpreting Spectroscopic Data: Electronic spectra (UV-Vis) are directly related to transitions between wavefunctions of different energy levels. Magnetic resonance parameters (e.g., in NMR and EPR) are exquisitely sensitive to the local electron probability density distribution, allowing for the interpretation of spectroscopic signatures in structural terms.

The wavefunction (ψ) and its associated probability density (|ψ|²) provide the essential link between the abstract mathematics of the Schrödinger equation and the tangible physical and chemical properties of matter. The Born interpretation—that |ψ|² gives the probability density for particle location—is the fundamental concept that enables this connection. While the computational determination of accurate wavefunctions for molecular systems remains a grand challenge, ongoing advancements in wavefunction-based electronic structure methods, composite protocols, and emerging machine-learning approaches like QiankunNet are continuously expanding the frontiers of what is possible. For researchers in drug development and related fields, a firm grasp of these principles and methodologies is crucial for leveraging quantum chemistry as a predictive tool for the rational design and discovery of new molecules and materials.

The Schrödinger equation stands as the foundational pillar of quantum chemistry, providing the mathematical framework to predict the behavior of electrons and nuclei within molecules. The solution of this equation for molecular systems unlocks the ability to compute critical properties such as molecular structure, reactivity, and spectroscopic behavior, which are essential for rational drug design. At the heart of the Schrödinger equation lies the Hamiltonian operator, an entity that encodes the total energy of the quantum system and completely determines its dynamics and stationary states. This technical guide explores the Hamiltonian operator within the broader thesis that solving the Schrödinger equation—by defining the appropriate Hamiltonian and finding its eigenfunctions—is the primary task of computational quantum chemistry research. For drug development professionals, these solutions enable the in silico prediction of molecular properties, reaction pathways, and binding affinities, thereby accelerating the discovery process.

The Hamiltonian operator, denoted as Ĥ, is a Hermitian operator that represents the sum of all kinetic and potential energy contributions within a system. As defined by the postulates of quantum mechanics, the time-independent Schrödinger equation is an eigenvalue equation: Ĥ|Ψ⟩ = E|Ψ⟩, where E is the scalar eigenvalue representing the total energy of the system in the state described by the wave function |Ψ⟩. The solutions to this equation define the stable stationary states of the system, with the eigenvalues corresponding to experimentally observable energy levels. For molecular systems, the complexity of the Hamiltonian increases dramatically with the number of electrons and nuclei, making the search for accurate, computationally tractable approximation methods a central theme in modern quantum chemistry research.

Theoretical Foundation: Deconstructing the Molecular Hamiltonian

The Coulomb Hamiltonian: A First-Principles Description

The most fundamental form for molecular systems is the Coulomb Hamiltonian, which provides a complete description of the energy for a collection of charged point particles—electrons and nuclei—interacting via electrostatic forces. The full Coulomb Hamiltonian (Ĥ_Coulomb) incorporates five distinct physical contributions that can be precisely written as follows [26]:

- The kinetic energy operators for each nucleus in the system: ( \hat{T}n = -\sum{i} \frac{\hbar^{2}}{2M{i}} \nabla{\mathbf{R}_{i}}^{2} )

- The kinetic energy operators for each electron in the system: ( \hat{T}e = -\sum{i} \frac{\hbar^{2}}{2m{e}} \nabla{\mathbf{r}_{i}}^{2} )

- The potential energy between the electrons and nuclei (electron-nucleus attraction): ( \hat{U}{en} = -\sum{i} \sum{j} \frac{Z{i}e^{2}}{4\pi\varepsilon{0}|\mathbf{R}{i} - \mathbf{r}_{j}|} )

- The potential energy arising from Coulombic electron-electron repulsions: ( \hat{U}{ee} = \frac{1}{2}\sum{i} \sum{j \neq i} \frac{e^{2}}{4\pi\varepsilon{0}|\mathbf{r}{i} - \mathbf{r}{j}|} )

- The potential energy arising from Coulombic nuclei-nuclei repulsions: ( \hat{U}{nn} = \frac{1}{2}\sum{i} \sum{j \neq i} \frac{Z{i}Z{j}e^{2}}{4\pi\varepsilon{0}|\mathbf{R}{i} - \mathbf{R}{j}|} )

Thus, the complete expression is: ĤCoulomb = T̂n + T̂e + Ûen + Ûee + Ûnn.

Table 1: Components of the Coulomb Hamiltonian for a Molecular System

| Component | Mathematical Expression | Physical Description | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nuclear Kinetic Energy | ( \hat{T}n = -\sum{i} \frac{\hbar^{2}}{2M{i}} \nabla{\mathbf{R}_{i}}^{2} ) | Energy from motion of nuclei | ||

| Electronic Kinetic Energy | ( \hat{T}e = -\sum{i} \frac{\hbar^{2}}{2m{e}} \nabla{\mathbf{r}_{i}}^{2} ) | Energy from motion of electrons | ||

| Electron-Nucleus Attraction | ( \hat{U}{en} = -\sum{i} \sum{j} \frac{Z{i}e^{2}}{4\pi\varepsilon_{0} | \mathbf{R}{i} - \mathbf{r}{j} | } ) | Coulomb attraction between opposite charges |

| Electron-Electron Repulsion | ( \hat{U}{ee} = \frac{1}{2}\sum{i} \sum{j \neq i} \frac{e^{2}}{4\pi\varepsilon{0} | \mathbf{r}{i} - \mathbf{r}{j} | } ) | Coulomb repulsion between electrons |

| Nuclear-Nuclear Repulsion | ( \hat{U}{nn} = \frac{1}{2}\sum{i} \sum{j \neq i} \frac{Z{i}Z{j}e^{2}}{4\pi\varepsilon{0} | \mathbf{R}{i} - \mathbf{R}{j} | } ) | Coulomb repulsion between nuclei |

The Born-Oppenheimer Approximation: Enabling Practical Computation

Solving the Schrödinger equation with the full Coulomb Hamiltonian is intractable for any system beyond the smallest molecules like H₂ due to the coupled motion of all particles. The Born-Oppenheimer approximation is a critical simplification that exploits the significant mass difference between electrons and nuclei. Since nuclei are thousands of times heavier than electrons, they move much more slowly. From the perspective of the electrons, the nuclei appear nearly stationary [26].

This allows the molecular Hamiltonian to be separated. The nuclear kinetic energy term (T̂n) is omitted, and the nuclei are treated as fixed in space, generating a static electrostatic potential in which the electrons move. This creates the electronic Hamiltonian (Ĥelec) for a specific nuclear configuration: Ĥelec = T̂e + Ûen + Ûee + Ûnn. Note that Ûnn, the nuclear repulsion energy, becomes a constant for a fixed nuclear arrangement.

Solving the electronic Schrödinger equation, Ĥelec |Ψelec⟩ = Eelec |Ψelec⟩, for various nuclear configurations (R) yields a potential energy surface, E_elec(R). This surface then serves as the potential energy term in a second Schrödinger equation that describes the nuclear motion (vibrations and rotations). This separation is the cornerstone of all practical computational chemistry, enabling the conceptual framework of molecular geometry and electronic structure.

Approximation Strategies for the Many-Body Problem

The electronic Schrödinger equation remains exceedingly difficult to solve exactly for multi-electron systems because of the electron-electron repulsion term (Û_ee). This term couples the motions of all electrons, making the equation a many-body problem that cannot be separated into independent one-electron equations. The complexity of finding exact solutions grows exponentially with the number of electrons [27]. Consequently, a hierarchy of approximation strategies has been developed, forming the methodological basis of modern quantum chemistry.

Table 2: Quantum Chemical Methods for Solving the Electronic Schrödinger Equation

| Method | Fundamental Approximation | Key Outputs | Computational Cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hartree-Fock (HF) | Models electrons as moving in an average field of other electrons; approximates Û_ee. | Molecular orbitals, orbital energies, total energy. | Low (Nâ´) |

| Post-Hartree-Fock Methods | Adds electron correlation missing in HF. | More accurate total and relative energies. | High (Nâµ to N! ) |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | Replaces many-electron wave function with electron density; models exchange & correlation. | Electron density, total energy, molecular properties. | Moderate (N³ to Nâ´) |

| Quantum Monte Carlo | Uses stochastic (random) sampling to solve the Schrödinger equation. | Very accurate energies, explicitly correlated wave function. | Very High |

| Semi-empirical Methods | Neglects or approximates many integrals; parameters fitted to experimental data. | Geometry, energy, charge distribution. | Very Low |

The core challenge is electron correlation, which is the error introduced by the mean-field approximation in Hartree-Fock theory. Post-Hartree-Fock methods systematically recover this correlation energy. Configuration Interaction (CI) expands the wave function as a linear combination of Slater determinants representing electronic excitations. Møller-Plesset Perturbation Theory (e.g., MP2) treats electron correlation as a small perturbation to the HF Hamiltonian. Coupled-Cluster (CC) methods, such as CCSD(T), use an exponential ansatz for the wave function operator and are considered the "gold standard" for single-reference molecular energy calculations [27].

Computational Protocol: From Hamiltonian to Molecular Properties

The following workflow diagram outlines the standard protocol for applying the Schrödinger equation in quantum chemistry studies, from system definition to property prediction.

Detailed Methodological Steps

System Definition and Geometry Input: The process begins with a precise definition of the molecular system, including the atomic numbers (Z) of all constituent atoms and their initial Cartesian coordinates in space. This structure can come from crystallographic data, molecular mechanics pre-optimization, or chemical intuition.

Hamiltonian Construction and Method Selection: The Born-Oppenheimer approximation is applied, fixing the nuclear coordinates. The electronic Hamiltonian is constructed, and a specific quantum chemistry method (e.g., DFT with the B3LYP functional and 6-31G* basis set) is selected based on the desired accuracy and available computational resources [28].

Wave Function Solution and Energy Calculation: The core computational step involves solving the electronic Schrödinger equation for the chosen method. This is typically an iterative procedure (self-consistent field for HF and DFT) that converges to a stable wave function (or electron density in DFT) and the corresponding electronic energy.

Property Computation and Analysis: The resulting wave function is a rich source of information. It is used to compute a wide array of molecular properties, including:

- Population Analysis: Atomic charges (e.g., Mulliken, Natural Population Analysis).

- Bonding Analysis: Molecular orbitals, bond orders.

- Spectroscopic Predictions: Simulated UV-Vis, IR, and NMR spectra derived from excited-state, vibrational, and magnetic calculations.

- Energetics: Reaction energies, barrier heights, and non-covalent interaction energies.

Application in Drug Discovery: For pharmaceutical researchers, these computed properties are critical. They can predict the binding affinity of a small molecule to a protein target, model the energy profile of a metabolic reaction, or optimize the photostability of a drug candidate by studying its excited-state properties [28].

Table 3: Key "Research Reagent Solutions" in Computational Quantum Chemistry

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function and Role |

|---|---|---|

| Basis Sets | 6-31G*, cc-pVDZ, def2-TZVP | Sets of mathematical functions (atomic orbitals) used to expand the molecular orbitals or electron density. They define the flexibility and accuracy of the calculation. |

| Electronic Structure Methods | B3LYP (DFT), ωB97X-D (DFT), MP2, CCSD(T) | The specific approximation to the electronic Hamiltonian and electron correlation that determines the accuracy of the energy and properties. |

| Solvation Models | PCM (Polarizable Continuum Model), SMD | Implicitly model the effects of a solvent environment on the molecular system, crucial for simulating biological conditions. |

| Potential Energy Surface Scanners | Nudged Elastic Band (NEB), Frequency Calculations | Algorithms to find minimum energy structures and transition states, and to verify their nature (minima have no imaginary frequencies). |

| High-Volume Datasets | QCDGE, QM9 [28] | Curated databases of pre-computed molecular properties for benchmarking methods and training machine learning models. |

Case Study: Large-Scale Dataset Construction for Ground and Excited States

A modern application of these protocols is the creation of large-scale, high-quality quantum chemistry datasets for machine learning. The recently developed QCDGE (Quantum Chemistry Dataset with Ground- and Excited-State Properties) dataset exemplifies this [28]. It contains 443,106 small organic molecules (up to 10 heavy atoms: C, N, O, F).

The experimental protocol for its construction was meticulous:

Initial Geometry Collection: Molecules were sourced from diverse and reputable databases (QM9, PubChemQC, GDB-11) to ensure chemical diversity. For GDB-11, initial 3D structures were generated from SMILES strings using Open Babel and pre-optimized at the GFN2-xTB semi-empirical level.

Ground-State Calculations: All molecules underwent geometry optimization and frequency calculations at the B3LYP/6-31G* level with D3 dispersion correction. This ensures all structures are at a minimum on the potential energy surface and provides thermodynamic properties.

Excited-State Calculations: Single-point calculations for the first ten singlet and triplet excited states were performed on the optimized geometries at the ωB97X-D/6-31G* level. This provides critical information for photochemistry and spectroscopy.

Property Extraction: Twenty-seven distinct molecular properties were extracted, including energies, orbitals, vibrational frequencies, and transition dipole moments. This dataset, built upon a consistent Hamiltonian and approximation method, is invaluable for training ML models to predict molecular properties rapidly, a powerful tool for accelerating high-throughput screening in drug discovery.

The Hamiltonian operator is the linchpin connecting the abstract formalism of quantum mechanics to the predictive power of computational chemistry. It is the mathematical embodiment of the physical system, encoding all kinetic and potential energy information. The entire endeavor of solving the Schrödinger equation in a chemical context hinges on defining the correct molecular Hamiltonian and then developing intelligent, computationally feasible strategies to approximate its solutions. From the foundational Born-Oppenheimer approximation to the sophisticated coupled-cluster methods used today, each advance provides a more accurate or efficient path to extracting the information contained within the Hamiltonian.

For researchers in drug development, this progression translates directly to enhanced capability. The ability to compute molecular structures, interaction energies, and spectroscopic signatures from first principles allows for the rational design of novel therapeutics and the interpretation of complex experimental data. As new approximation methods emerge and computational power grows, the role of the Hamiltonian and the Schrödinger equation in de-risking and guiding the drug discovery pipeline will only become more profound.

The Schrödinger equation represents the cornerstone of quantum mechanics, providing the fundamental mathematical framework for describing the behavior of physical systems at atomic and subatomic scales. In quantum chemistry research, this equation enables scientists to predict the properties, reactivity, and dynamics of molecules with remarkable accuracy. Central to this framework are the concepts of eigenfunctions and eigenvalues, which emerge naturally when solving the Schrödinger equation for quantum systems. These mathematical entities provide the crucial link between abstract theory and physically observable quantities, allowing researchers to determine the allowable energy states of electrons in atoms and molecules—information that proves indispensable in drug design and materials science. The time-independent Schrödinger equation, expressed as Ĥψ = Eψ [29] [30], forms an eigenvalue equation where Ĥ is the Hamiltonian operator (representing the total energy of the system), ψ is the eigenfunction (wavefunction), and E is the eigenvalue (allowed energy value) [31]. This mathematical structure underpins our understanding of molecular structure and plays a pivotal role in computational chemistry approaches used throughout pharmaceutical research and development.

Theoretical Foundations: Eigenvalue Equations in Quantum Mechanics

Mathematical Framework of Eigenvalue Problems

In quantum mechanics, the eigenvalue equation represents a fundamental mathematical structure where an operator acting on a function yields a scalar multiple of that same function [32]. The general form of an eigenvalue equation is:

Âψ = aψ

Here, Â represents a linear operator corresponding to a physical observable, ψ denotes the eigenfunction (or eigenstate), and a signifies the eigenvalue—the measurable value of the observable when the system is in state ψ [29] [31]. This mathematical relationship ensures that the eigenfunction maintains its functional form under the operation of Â, merely being scaled by the eigenvalue. When the operator in question is the Hamiltonian (Ĥ), which represents the total energy operator, the resulting eigenvalue equation becomes the time-independent Schrödinger equation, with eigenvalues corresponding to the quantized energy levels allowable for the system [29] [30].

The Hamiltonian operator itself consists of two fundamental components: the kinetic energy operator and the potential energy operator [29] [33]. Mathematically, this is expressed as:

Ĥ = - (Ⅎ/2m)∇² + VÌ‚(r)

where the first term represents the kinetic energy operator (with ℠denoting the reduced Planck constant, m the particle mass, and ∇² the Laplacian operator accounting for second derivatives in space), and the second term V̂(r) represents the potential energy operator, which varies depending on the specific physical system under investigation [29].

Physical Interpretation of Eigenfunctions and Eigenvalues

In the quantum mechanical framework, eigenfunctions (ψ) describe the stationary states of a system, representing wavefunctions whose probability densities remain constant over time [34]. Each eigenfunction provides complete information about the spatial distribution of a particle in that particular quantum state, with |ψ(x)|² representing the probability density of finding the particle at position x [31]. The eigenvalues (E), being real numbers for physical observables, correspond to the precise values of measurable quantities when the system resides in the associated eigenstate [31] [32]. For energy eigenvalues specifically, these values represent the quantized energy levels that a quantum system can possess—a fundamental departure from classical mechanics where energy can vary continuously [34].

When a quantum system is in a stationary state (an eigenstate of the Hamiltonian), its properties exhibit remarkable stability: the probability density remains time-independent, expectation values of observables are constant, and no energy exchange occurs with the environment [34]. This stability makes these states particularly important for investigating molecular structure and properties. The orthonormality of eigenfunctions—where the inner product ⟨ψ_i|ψ_j⟩ equals zero for different states and unity for the same state—ensures they form a complete basis set [31]. This property allows any general wavefunction to be expressed as a linear combination of these eigenfunctions, enabling researchers to describe complex quantum states and their time evolution through the superposition principle [33] [34].

Table: Fundamental Properties of Quantum Mechanical Eigenfunctions and Eigenvalues

| Property | Mathematical Expression | Physical Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Eigenvalue Equation | Ĥψ_n = E_nψ_n |

Defines stationary states with precise energy values |

| Orthonormality | ⟨ψ_m⎥ψ_n⟩ = δ_mn |

Ensures eigenfunctions are perpendicular and normalized |

| Completeness | Ψ = Σ c_nψ_n |

Any state can be expanded as a sum of eigenfunctions |

| Probability Density | P(x) = ⎥ψ(x)⎥² |

Probability of finding particle at position x |

| Energy Quantization | E_n = discrete values |

Energy restricted to specific allowed values |

Fundamental Quantum Systems: Eigenfunctions and Eigenvalues

Analytical Solutions for Model Systems

Several quantum systems exist for which the Schrödinger equation admits exact analytical solutions, providing crucial insights into the relationship between physical potentials and their corresponding eigenfunctions and eigenvalues. These model systems serve as foundational concepts in quantum chemistry and offer valuable test cases for computational methods.

The particle in a one-dimensional box (infinite square well) represents one of the simplest quantum systems with exact solutions. Here, a particle is confined between impenetrable walls at x = 0 and x = L, creating a potential energy function that is zero inside the box and infinite outside. The resulting eigenfunctions and eigenvalues are:

ψ_n(x) = √(2/L) sin(nπx/L)

E_n = (n²π²â„²)/(2mL²) = (n²h²)/(8mL²) [31] [34]

where n = 1, 2, 3,... is the quantum number, m is the particle mass, and L is the box width. These solutions demonstrate fundamental quantum principles: energy quantization (discrete energy levels), zero-point energy (lowest energy ≠0), and the relationship between confinement length and energy level spacing.

The quantum harmonic oscillator models systems with parabolic potentials, such as molecular vibrations, with potential energy V(x) = (1/2)mω²x². Its solutions are:

ψ_n(x) = (1/√(2â¿n!)) (mω/Ï€â„)^(1/4) e^(-mωx²/2â„) H_n(√(mω/â„)x)

E_n = (n + 1/2)â„ω [31] [34] [30]

where n = 0, 1, 2,..., ω is the oscillator frequency, and H_n are Hermite polynomials. The harmonic oscillator exhibits equal energy spacing (â„ω) and significant probability in classically forbidden regions, with the ground state energy ((1/2)â„ω) representing the quantum zero-point energy.

The hydrogen atom provides the most important exactly solvable system in quantum chemistry, with a Coulomb potential V(r) = -e²/(4πε₀r). Its eigenfunctions and eigenvalues are:

E_n = - (13.6 eV)/n² [31] [34] [30]

where n = 1, 2, 3,... is the principal quantum number. The corresponding eigenfunctions are atomic orbitals characterized by quantum numbers n, l, and m_l, with radial components involving Laguerre polynomials and angular components given by spherical harmonics [31] [34]. The hydrogen atom solutions explain atomic spectra and provide the foundational orbital concept that underpins all of quantum chemistry.

Table: Comparison of Eigenfunctions and Eigenvalues in Fundamental Quantum Systems

| Quantum System | Potential Energy | Eigenvalues | Quantum Numbers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Particle in a Box | 0 inside, ∞ outside |

E_n = n²h²/(8mL²) |

n = 1, 2, 3, ... |

| Harmonic Oscillator | V(x) = ½mω²x² |

E_n = (n + ½)â„ω |

n = 0, 1, 2, ... |

| Hydrogen Atom | V(r) = -e²/(4πε₀r) |

E_n = -13.6 eV/n² |

n, l, m_l |

Computational Methodologies for Complex Systems

Numerical Approaches for Eigenvalue Determination

While analytical solutions exist for idealized quantum systems, most chemically relevant molecules require numerical methods to solve the Schrödinger equation and determine eigenvalues and eigenfunctions. These computational approaches form the backbone of modern quantum chemistry and enable the application of quantum principles to drug discovery and materials design.

The variational method provides a powerful approach for approximating the ground state energy and wavefunction of quantum systems [31] [34]. This method relies on the variational principle, which states that for any trial wavefunction ψ_trial, the expectation value of the energy satisfies ⟨E⟩ = ⟨ψ_trial|Ĥ|ψ_trial⟩/⟨ψ_trial|ψ_trial⟩ ≥ E_0, where E_0 is the true ground state energy. The methodology involves: (1) selecting a flexible trial wavefunction with adjustable parameters, (2) computing the energy expectation value as a function of these parameters, and (3) minimizing this energy with respect to the parameters. The resulting minimized energy provides an upper bound to the true ground state energy, while the corresponding wavefunction approximates the true ground state wavefunction. In practice, quantum chemists employ basis set expansions where the trial wavefunction is expressed as a linear combination of known basis functions, transforming the problem into a matrix eigenvalue equation [32].

Matrix diagonalization techniques represent another fundamental approach for solving quantum mechanical eigenvalue problems [31] [32]. This method involves representing the Hamiltonian operator as a matrix in a chosen basis set, then diagonalizing this matrix to obtain eigenvalues and eigenvectors. The computational protocol includes: (1) selecting an appropriate basis set {φ_i} that spans the Hilbert space of the system, (2) computing matrix elements H_ij = ⟨φ_i|Ĥ|φ_j⟩ of the Hamiltonian, (3) constructing the Hamiltonian matrix H, (4) solving the matrix eigenvalue equation HC = SCε (where S_ij = ⟨φ_i|φ_j⟩ is the overlap matrix for non-orthogonal basis functions), and (5) extracting the eigenvalues ε (energies) and eigenvectors C (wavefunction coefficients). This approach effectively reduces the differential eigenvalue problem to an algebraic one, making it amenable to computational solution even for complex molecular systems.

The shooting method offers a numerical approach for solving one-dimensional eigenvalue problems [31] [34]. This technique is particularly useful for problems with non-standard potentials where analytical solutions are unavailable. The algorithm proceeds as follows: (1) guess an eigenvalue E, (2) integrate the Schrödinger equation numerically from one boundary to the other, (3) check whether the solution satisfies the boundary conditions, (4) adjust E systematically until the boundary conditions are satisfied. The method leverages numerical integration techniques (such as Runge-Kutta methods) and root-finding algorithms (such as the bisection or Newton-Raphson methods) to converge to the correct eigenvalues. While primarily applicable to one-dimensional problems, the shooting method provides valuable insights into the relationship between potentials and their corresponding wavefunctions and energies.

Basis Sets and Approximation Methods

In computational quantum chemistry, the choice of basis set profoundly influences the accuracy and efficiency of eigenvalue calculations. Basis sets typically consist of atomic orbitals (such as Gaussian-type orbitals or Slater-type orbitals) centered on atomic nuclei, with the molecular wavefunction expanded as a linear combination of these atomic orbitals (LCAO method). The quality of a basis set depends on its size (number of basis functions per atom) and flexibility (ability to describe electron distribution accurately), with more extensive basis sets generally providing higher accuracy at increased computational cost.