Variational Quantum Eigensolver: Calculating Molecular Ground States for Quantum-Accelerated Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) for determining molecular ground states, a critical task in computational chemistry with profound implications for drug development.

Variational Quantum Eigensolver: Calculating Molecular Ground States for Quantum-Accelerated Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) for determining molecular ground states, a critical task in computational chemistry with profound implications for drug development. We explore the foundational principles of VQE and its hybrid quantum-classical architecture, tailored for Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) devices. The content details methodological components—from ansatz selection to Hamiltonian measurement—and addresses key optimization challenges, including performance benchmarking of classical optimizers under quantum noise. Finally, we examine validation strategies and comparative analyses with classical methods, synthesizing the current capabilities and future trajectory of VQE for enabling breakthroughs in biomedical research.

Quantum Principles and the VQE Framework: A Hybrid Approach for Molecular Simulation

Simulating the behavior of molecules is a fundamental challenge in chemistry, material science, and drug development. The core of this problem lies in solving the Schrödinger equation to determine the electronic structure of a molecule, which in turn dictates its properties, reactivity, and interactions. However, the mathematical complexity of this task grows exponentially with the number of electrons and orbitals in the system. For classical computers, this exponential scaling presents a fundamental barrier; simulating even moderately-sized molecules with high accuracy becomes computationally intractable [1] [2].

Quantum computers, which operate using quantum mechanical principles themselves, offer a promising path to overcome this limitation. This application note, framed within ongoing research on the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE), explores the reasons behind the failures of classical computational chemistry methods and outlines how hybrid quantum-classical algorithms are poised to provide a decisive quantum advantage for molecular simulation.

The Classical Bottleneck: Wave Function Methods and Exponential Scaling

Classical computational chemistry relies on a hierarchy of methods to approximate the solutions of the time-independent Schrödinger equation, represented as Ĥ |Ψ⟩ = E |Ψ⟩, where Ĥ is the electronic Hamiltonian and E is the energy [1]. The following table summarizes the key classical methods and their limitations.

Table 1: Classical Computational Chemistry Methods for the Electronic Structure Problem

| Method | Key Approximation | Scaling Complexity | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hartree-Fock (HF) | Single determinant (electron correlation neglected) | Polynomial (O(Nâ´)) [1] | Fails for strongly correlated systems; inaccurate dissociation energies [1] [3] |

| Coupled Cluster Singles & Doubles (CCSD) | Exponential ansatz with single & double excitations [3] | O(Nâ¶) | High computational cost; still struggles with strong correlation [4] |

| Full Configuration Interaction (FCI) | Exact solution within the given basis set [1] | Exponential (O(eâ¿)) [1] | Computationally impossible for all but the smallest molecules [1] [3] |

The central challenge is the exponential growth of the Hilbert space. For a system with M spin-orbitals, the number of possible electronic configurations is 2^M. The FCI method, which considers all possible configurations, is exact but is only feasible for very small molecules like hydrogen in a minimal basis [1]. While methods like CCSD provide an excellent cost-accuracy trade-off for many systems near equilibrium, they are not variational and can fail dramatically for systems involving bond breaking or other strongly correlated phenomena [3] [4]. This is a critical bottleneck for drug development, where understanding reaction pathways and excited states often involves precisely these scenarios.

The Quantum Approach: The Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE)

The VQE is a hybrid quantum-classical algorithm designed to leverage the strengths of both types of processors for the NISQ era [5] [4]. It uses the quantum computer to efficiently prepare and measure complex trial wavefunctions that would be intractable for a classical computer to represent, while a classical optimizer adjusts the parameters of the quantum circuit to minimize the energy expectation value [6].

Core VQE Protocol

The following workflow details the standard VQE procedure for estimating a molecular ground state energy.

Experimental Protocol 1: Standard VQE Workflow

Problem Formulation (Classical Computer):

- Input: Define the molecular geometry, atomic basis set (e.g., STO-3G), and charge/spin multiplicity [1].

- Hamiltonian Generation: Perform a classical Hartree-Fock calculation. Transform the resulting electronic Hamiltonian into a qubit-representation using a mapping such as the Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev transformation [2]. The Hamiltonian takes the form

H_Q = Σ_j g_j ⨂_μ σ_{j,μ}, a sum of Pauli words (I,X,Y,Z) with coefficientsg_j[2].

Ansatz Selection (Classical Computer):

Quantum Subroutine (Quantum Computer):

- Prepare the trial state

|Ψ(θ)⟩on the quantum processor. - Measure the expectation value

⟨Ψ(θ)| H_Q |Ψ(θ)⟩by decomposing it into a sum of expectation values of the individual Pauli terms⟨Ψ(θ)| ℙ_j |Ψ(θ)⟩[3] [6]. This requires many repeated state preparations and measurements to achieve sufficient statistical accuracy.

- Prepare the trial state

Classical Optimization (Classical Computer):

- The classical optimizer (e.g., COBYLA, SPSA) uses the energy reported by the quantum computer as the cost function.

- The optimizer proposes new parameters

θ_newto minimize the energy. - Steps 3 and 4 are repeated iteratively until convergence to a minimum energy is achieved [6].

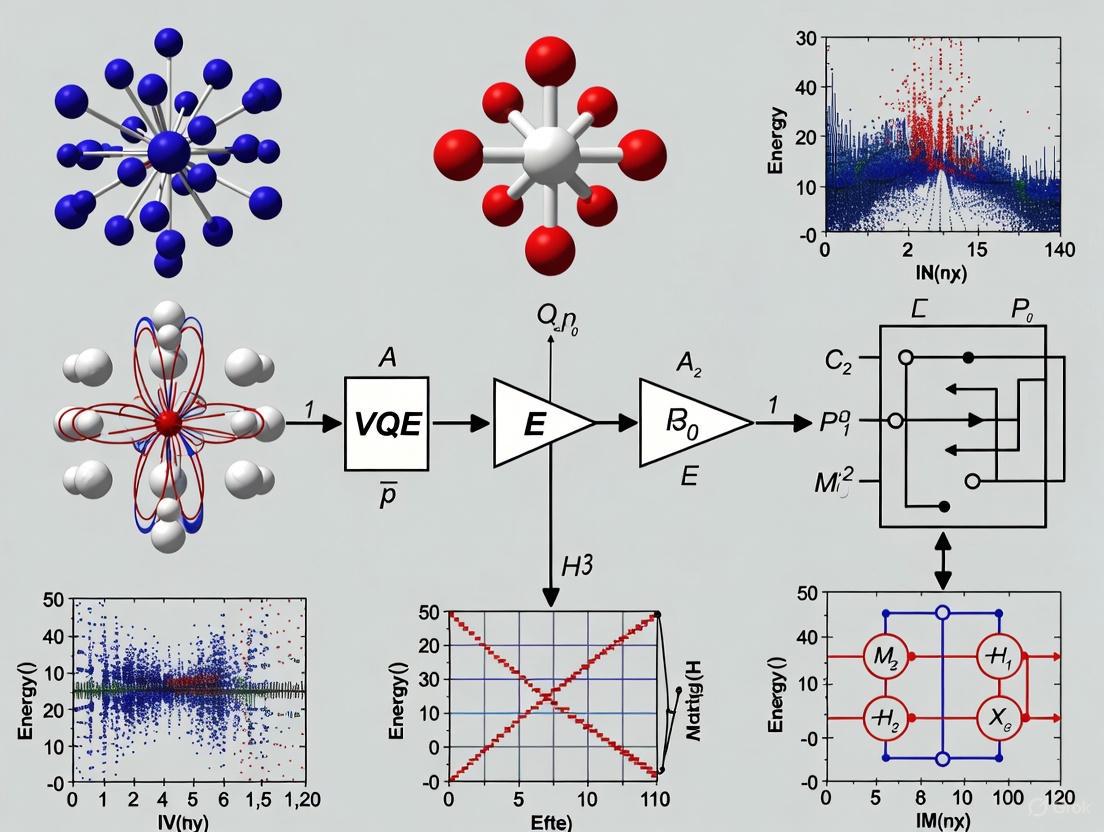

Figure 1: VQE Hybrid Quantum-Classical Workflow.

Advanced VQE Protocols: Overcoming Ansatz Limitations with ADAPT-VQE

A significant limitation of standard VQE is its reliance on a pre-selected, fixed ansatz (like UCCSD), which may be inefficient or inaccurate for strongly correlated systems [3]. The ADAPT-VQE algorithm addresses this by dynamically growing a compact, problem-specific ansatz.

ADAPT-VQE Protocol

Experimental Protocol 2: ADAPT-VQE Algorithm

Initialization:

Iterative Ansatz Construction:

- For each step

k: a. Gradient Evaluation: For every operatorτ_nin the poolA, compute the energy gradient∂E/∂θ_n ≈ ⟨Ψ_k| [H, τ_n] |Ψ_k⟩. This requires measuring the expectation values of these commutators on the quantum computer [3] [4]. b. Operator Selection: Identify the operatorτ_{max}with the largest magnitude gradient. c. Ansatz Expansion: Append the corresponding unitaryexp(θ_{k+1} τ_{max})to the circuit, initializing the new parameterθ_{k+1} = 0[3]. d. Circuit Optimization: Re-optimize all parameters{θ_1, ..., θ_{k+1}}in the new, longer circuit to minimize the energy [3].

- For each step

Termination:

- The algorithm iterates until the norm of the gradient vector falls below a predefined threshold, indicating that a (local) minimum has been reached and the ansatz is sufficiently expressive [3].

Recent advancements have dramatically improved ADAPT-VQE's efficiency. The introduction of the Coupled Exchange Operator (CEO) pool, for instance, has been shown to reduce CNOT gate counts and circuit depths by up to 88% and 96%, respectively, compared to the original algorithm [7]. Furthermore, the "batched ADAPT-VQE" approach, which adds multiple high-gradient operators in a single iteration, can significantly reduce the measurement overhead associated with the gradient evaluation step [4].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of VQE Algorithms for Representative Molecules

| Algorithm | Molecule (Qubits) | CNOT Count at Chemical Accuracy | Key Advantage | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VQE-UCCSD | Hâ‚‚ (4 qubits) | Low (in this small case) [6] | Well-established chemistry-inspired ansatz [4] | Inefficient and inaccurate for strong correlation [3] [4] |

| Original ADAPT-VQE [3] | LiH (12 qubits) | Baseline | Compact, problem-tailored ansatz [3] | High measurement cost from gradient evaluations [4] |

| CEO-ADAPT-VQE* [7] | LiH (12 qubits) | ~88% reduction vs. original ADAPT [7] | Dramatically reduced circuit depth & measurement cost [7] | Increased classical complexity in pool construction |

The following table catalogs key "research reagents" — the computational tools and methodologies — required for implementing VQE experiments in molecular simulation.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for VQE Molecular Simulation

| Reagent / Resource | Function / Description | Example Implementations |

|---|---|---|

| Classical Electronic Structure Package | Precomputes molecular integrals, Hartree-Fock orbitals, and generates the fermionic Hamiltonian. | PySCF [1] |

| Fermion-to-Qubit Mapping | Encodes the fermionic Hamiltonian and wavefunctions into the qubit representation. | Jordan-Wigner Transformation [2], Bravyi-Kitaev Transformation |

| Operator Pool (for ADAPT-VQE) | A predefined set of operators from which the adaptive ansatz is constructed. | Fermionic (UCCSD) Pool [4], Qubit Pool [4], CEO Pool [7] |

| Quantum Simulator / Hardware | Executes the parameterized quantum circuits and returns measurement statistics. | Statevector Simulator (e.g., MindQuantum [1], PennyLane [6]), NISQ Hardware (e.g., IBM Quantum [5]) |

| Classical Optimizer | Variationally updates the quantum circuit parameters to minimize the energy. | COBYLA [5], Gradient Descent [6], SPSA |

Current Limitations and Future Directions

Despite its promise, VQE faces significant challenges on current hardware. Quantum noise is the most formidable obstacle; the limited coherence times and gate infidelities of NISQ devices prevent the execution of deep quantum circuits and corrupt measurement results. A recent study concluded that the noise levels in today's devices "prevent meaningful evaluations of molecular Hamiltonians with sufficient accuracy" [5]. Furthermore, the measurement cost of estimating the energy from a large number of Pauli terms is substantial, and classical optimization can be hindered by barren plateaus [7] [4].

Future research is focused on co-designing algorithms and hardware to overcome these barriers. This includes:

- Improved Error Mitigation: Developing techniques to subtract or correct for noise effects in computations.

- More Efficient Ansätze: Continuing to refine adaptive (ADAPT-VQE) and hardware-efficient ansätze to minimize circuit depth [7] [8].

- Algorithmic Acceleration: Leveraging classical pre-processing and high-performance computing resources, such as the Sparse Wave function Circuit Solver (SWCS), to reduce the quantum computational load [8].

- Novel Hardware Architectures: Exploring alternative platforms, such as bosonic qumodes in circuit quantum electrodynamics, which may offer more efficient state preparation for certain problems [2].

The path to a definitive quantum advantage in molecular simulation is steep, but the rapid progress in VQE algorithms and the iterative improvement of quantum hardware provide a clear and promising roadmap for researchers in chemistry and drug development.

The variational principle is a cornerstone of quantum mechanics, providing a powerful method for approximating the properties of quantum systems, most notably the ground state energy. This principle states that for any trial wavefunction ( |\psi(\vec{\theta})\rangle ), the expectation value of the Hamiltonian ( \hat{H} ) is always greater than or equal to the true ground state energy ( E0 ): [ E[\psi(\vec{\theta})] = \frac{\langle\psi(\vec{\theta})|\hat{H}|\psi(\vec{\theta})\rangle}{\langle\psi(\vec{\theta})|\psi(\vec{\theta})\rangle} \geq E0. ] This fundamental inequality forms the theoretical foundation of the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE), a hybrid quantum-classical algorithm designed to solve for ground states of molecular and many-body quantum Hamiltonians on noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices [9]. By constructing a parameterized trial wavefunction (ansatz) on a quantum processor and measuring its energy expectation value, VQE leverages the variational principle to approach the true ground state energy from above through classical optimization of the quantum circuit parameters [9]. This approach provides a practical alternative to quantum phase estimation, avoiding prohibitively deep circuits and extensive ancillary qubits, thus making it particularly suitable for current quantum hardware limitations [9].

Theoretical Framework: From Quantum Principle to Hybrid Algorithm

The VQE Algorithmic Framework

The standard VQE protocol implements the variational principle through a tightly coupled hybrid workflow between quantum and classical computing resources. The quantum computer's role is to prepare a parameterized quantum state ( |\psi(\vec{\theta})\rangle = U(\vec{\theta})|0\rangle ) and measure the expectation value of the Hamiltonian ( \hat{H} ), which is typically decomposed into a sum of Pauli strings [9]. This process begins with the preparation of an initial state, often the Hartree-Fock reference state in quantum chemistry applications, followed by application of a parameterized quantum circuit (ansatz) that introduces correlations [10].

The heart of the VQE algorithm lies in the iterative optimization loop where the classical computer adjusts the parameters ( \vec{\theta} ) to minimize the energy expectation value ( E(\vec{\theta}) = \langle\psi(\vec{\theta})|\hat{H}|\psi(\vec{\theta})\rangle ) based on measurement results from the quantum processor [9]. This hybrid approach makes VQE particularly well-suited for NISQ devices because it trades circuit depth for repeated measurements and classical optimization, effectively leveraging the strengths of both quantum and classical computing paradigms while mitigating the limitations of current quantum hardware [9].

Mathematical Foundation and Hamiltonian Transformation

The implementation of VQE requires mapping the electronic structure Hamiltonian from a fermionic representation to a qubit representation using mathematical transformations such as the Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev transformations [9]. The molecular Hamiltonian in the second quantization form is expressed as: [ \hat{H} = \sum{pq} h{pq} ap^\dagger aq + \frac{1}{2} \sum{pqrs} h{pqrs} ap^\dagger aq^\dagger ar as, ] where ( h{pq} ) and ( h{pqrs} ) are one- and two-electron integrals, and ( ap^\dagger ) and ( ap ) are fermionic creation and annihilation operators [9]. After transformation to qubit representation, the Hamiltonian becomes a linear combination of Pauli strings: [ \hat{H} = \sum{i} ci Pi, ] where ( Pi ) are Pauli operators (tensor products of I, X, Y, Z) and ( c_i ) are real coefficients [9]. This transformation enables the measurement of the energy expectation value through quantum measurements of individual Pauli operators.

Table: Key Mathematical Components of VQE Implementation

| Component | Mathematical Representation | Role in VQE Algorithm | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Hamiltonian | (\hat{H} = \sum{pq} h{pq} ap^\dagger aq + \frac{1}{2} \sum{pqrs} h{pqrs} ap^\dagger aq^\dagger ar as) | Defines the quantum system under study | ||

| Qubit Hamiltonian | (\hat{H} = \sum{i} ci P_i) | Enables quantum measurement through Pauli decomposition | ||

| Energy Expectation | (E(\vec{\theta}) = \langle\psi(\vec{\theta}) | \hat{H} | \psi(\vec{\theta})\rangle) | Objective function for variational minimization |

| Variational Principle | (E[\psi(\vec{\theta})] \geq E_0) | Theoretical foundation guaranteeing upper bound property |

VQE Protocol and Implementation

Core VQE Workflow

The execution of VQE follows a structured workflow that integrates both quantum and classical computing resources in an iterative loop. The algorithm begins with the initialization of parameters and preparation of an initial reference state on the quantum processor, typically the Hartree-Fock state for molecular systems [10]. The quantum computer then executes the parameterized quantum circuit (ansatz) that generates the trial wavefunction, after which measurements are performed to estimate the expectation values of the Hamiltonian terms [9].

The measurement phase is often the most resource-intensive part of the algorithm, as it requires repeated circuit executions to achieve sufficient statistical precision for each Pauli term in the Hamiltonian decomposition [10]. These measurement results are then combined classically to compute the total energy expectation value, which serves as the objective function for the classical optimizer [9]. The optimizer subsequently adjusts the circuit parameters to lower the energy, and this process repeats until convergence criteria are met, yielding an approximation to the ground state energy and wavefunction [9].

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Components for VQE Implementation

Table: Essential Components for VQE Experimental Implementation

| Component | Function/Role | Examples/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Processing Unit (QPU) | Executes parameterized quantum circuits and performs measurements | 25-qubit error-mitigated QPU for Ising model simulation [10] |

| Hamiltonian Representation | Encodes the physical system into qubit operations | Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev transformations to Pauli sums [9] |

| Variational Ansatz | Parameterized circuit generating trial wavefunctions | UCCSD, hardware-efficient, or adaptive ansätze [9] |

| Classical Optimizer | Adjusts circuit parameters to minimize energy | Gradient-based, gradient-free, or noise-resilient optimizers [10] |

| Operator Pool | Collection of unitary operators for adaptive ansatz construction | Typically contains fermionic or qubit excitation operators [10] |

| Error Mitigation Techniques | Reduces impact of noise on measurement results | Readout error mitigation, zero-noise extrapolation [10] |

Advanced VQE Methodologies

Adaptive Ansatz Construction: ADAPT-VQE

The ADAPT-VQE protocol represents a significant advancement over fixed-ansatz approaches by dynamically constructing problem-tailored quantum circuits [10]. This method addresses a fundamental challenge in VQE implementation: the selection of an appropriate ansatz that balances expressibility with circuit depth constraints of NISQ devices [10]. The adaptive procedure builds the ansatz iteratively by selecting the most relevant operators from a predefined pool at each step, effectively growing the circuit architecture based on chemical or physical relevance rather than using a predetermined structure [10].

The mathematical core of the ADAPT-VQE selection criterion identifies the unitary operator ( \mathscr{U}^* ) from pool ( \mathbb{U} ) that maximizes the energy gradient magnitude at the current iteration [10]: [ \mathscr{U}^* = \underset{\mathscr{U} \in \mathbb{U}}{\text{argmax}} \left| \frac{d}{d\theta} \Big \langle \Psi^{(m-1)} \left| \mathscr{U}(\theta)^\dagger \widehat{A} \mathscr{U}(\theta) \right| \Psi^{(m-1)} \Big \rangle \Big \vert {\theta=0} \right|. ] This greedy selection strategy ensures that each added operator provides the greatest potential energy reduction, leading to more compact and chemically meaningful circuits compared to fixed ansätze [10]. The resulting ansatz wavefunction takes the form ( |{\Psi}^{(m)}(\theta{m}, \theta{m-1}, \ldots, \theta{1})\rangle = \mathscr{U}^*(\theta{m})|\Psi^{(m-1)}(\theta{m-1}, \ldots, \theta_{1})\rangle ), with all parameters optimized globally after each operator addition [10].

Quantum Gaussian Filter VQE

The Quantum Gaussian Filter (QGF) VQE introduces an alternative approach that discretizes the QGF operator into a series of small-step evolutions, each simulated using VQE to update parameters so the quantum state approximates the evolved state after each step [11]. This method leverages the QGF operator's capability to converge an initial quantum state toward the ground state of a target Hamiltonian through an iterative parameter updating process [11]. Starting from an initial state represented by initial parameters, this approach enables approximation of the QGF-evolved state, ultimately converging to the ground state of the target Hamiltonian with shallower circuits compared to conventional methods [11].

The QGF-VQE methodology represents a fusion of filtering techniques with variational principles, specifically designed to address ground-state problems in quantum many-body systems while maintaining compatibility with NISQ device constraints [11]. Numerical demonstrations on models such as the Transverse Field Ising Model Hamiltonian ( \hat{H} = -J\sum{n=1}^{N}\hat{\sigma}{n}^{z}\hat{\sigma}{n+1}^{z} + g\sum{n=1}^{N}\hat{\sigma}_{n}^{x} ) have shown the method's effectiveness in preparing accurate ground states with resource-efficient quantum circuits [11].

Algorithmic Enhancements and Constraint Incorporation

Recent advancements in VQE methodologies have introduced sophisticated enhancements to address fundamental challenges in quantum simulation. Constraint incorporation has emerged as a crucial technique for maintaining physical meaningfulness throughout the optimization process [9]. By modifying the cost function to include penalty terms that enforce physical constraints such as fixed electron number or spin symmetries, this approach ensures the variational optimization cannot collapse into unphysical sectors [9]: [ E{\text{constrained}}(\Omega, \tau, \mu) = \langle\Psi(\Omega, \tau)|H|\Psi(\Omega, \tau)\rangle + \sumi \mui \left( \langle\Psi(\Omega, \tau)|\hat{C}i|\Psi(\Omega, \tau)\rangle - C_i \right)^2. ] This constrained VQE framework enables isolation of specific molecular sectors including cations, anions, radicals, and excited spin/charge states, significantly expanding the algorithm's utility for complex chemical systems [9].

Other notable enhancements include evolutionary circuit construction approaches that dynamically evolve circuit topology and parameters using genetic operators, achieving shallower circuits with superior noise resilience compared to fixed ansätze [9]. The variance minimization VQE (VVQE) reformulates the optimization target from energy expectation to energy variance, allowing direct targeting and verification of both ground and excited states [9]. Classical-quantum hybrid strategies such as contextual subspace VQE partition the Hamiltonian into classically simulable noncontextual parts and quantum-corrected contextual subspaces, dramatically reducing quantum resource demands [9].

Table: Advanced VQE Methodologies and Applications

| Methodology | Key Innovation | Demonstrated Application |

|---|---|---|

| ADAPT-VQE | Iterative, gradient-based operator selection | Hâ‚‚O and LiH molecules with reduced circuit depth [10] |

| GGA-VQE | Greedy gradient-free optimization | 25-qubit Ising model on error-mitigated hardware [10] |

| QGF-VQE | Quantum Gaussian filtering with variational steps | Transverse Field Ising Model ground states [11] |

| Constrained VQE | Penalty terms in cost function for physical constraints | Smooth potential energy surfaces, correct electron count [9] |

| Evolutionary VQE | Genetic algorithm-based circuit design | Hardware-adaptive shallow circuits for optimization problems [9] |

| ClusterVQE | Problem decomposition into coupled clusters | Reduced circuit width/depth, noise resilience [9] |

Experimental Protocols and Validation

Molecular Simulation Protocol

The standard experimental protocol for molecular ground state calculation using VQE begins with classical pre-processing steps including geometry optimization of the molecular structure, computation of one- and two-electron integrals using classical electronic structure methods, and selection of an appropriate active space if necessary [9]. The molecular Hamiltonian is then transformed into a qubit representation using Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev transformations, resulting in a linear combination of Pauli operators [9].

The quantum computational phase involves initializing the qubit register to the Hartree-Fock state, which serves as the reference wavefunction [10]. The parameterized ansatz circuit is then applied, with the specific form depending on the selected methodology (UCCSD, hardware-efficient, or adaptive) [9]. For each set of parameters, the energy expectation value is measured through repeated preparation and measurement of the quantum state for all Pauli terms in the Hamiltonian decomposition [9]. The measurement strategy often employs grouping techniques to minimize the number of distinct circuit executions required [10].

The classical optimization loop processes these measurement results to compute the total energy and potentially its gradients, then updates the circuit parameters using algorithms such as gradient descent, Bayesian optimization, or the simultaneous perturbation stochastic approximation (SPSA) [10]. Convergence is typically assessed based on energy changes between iterations, parameter stability, or gradient magnitudes, with final results validated against classical reference calculations when available [9].

GGA-VQE Implementation for Noisy Hardware

The Greedy Gradient-free Adaptive VQE (GGA-VQE) protocol represents a specialized implementation designed specifically to address the challenges of NISQ devices, particularly their susceptibility to statistical sampling noise [10]. This method simplifies the global optimization step in adaptive VQE while maintaining effectiveness in the presence of measurement uncertainty [10]. The algorithm has been demonstrated on a 25-qubit error-mitigated quantum processing unit for computing the ground state of a 25-body Ising model, showcasing its practical applicability to problems at scales beyond classical simulation [10].

A critical aspect of the GGA-VQE implementation is the validation methodology employed to assess performance despite hardware inaccuracies [10]. Although hardware noise on the QPU produces inaccurate energy measurements, researchers validated the approach by retrieving the parameterized operators calculated on the QPU and evaluating the resulting ansatz wavefunction via noiseless emulation through hybrid observable measurement [10]. This validation strategy confirms that despite noise limitations during optimization, the quantum processor can generate high-quality parameterized circuits that approximate ground states when evaluated in more controlled conditions [10].

Challenges and Future Directions

Despite significant advances, VQE methodologies face persistent challenges that represent active research frontiers. The barren plateau phenomenon, where gradients vanish exponentially with system size for random or unstructured ansätze, remains a fundamental obstacle to scalability [9]. This issue is particularly pronounced for hardware-efficient ansätze and is influenced by mapping choices, with recent research focusing on adaptive ansätze and problem-informed initializations to mitigate gradient disappearance [9].

The quantum resource requirements for measurement and optimization present substantial bottlenecks, especially for larger systems where measurement budgets and noisy hardware dominate performance [10] [9]. Current research addresses these challenges through advanced measurement strategies that reduce the number of circuit executions required, including operator grouping techniques and classical-shadow approaches [10]. Additionally, error mitigation techniques such as readout error correction, zero-noise extrapolation, and probabilistic error cancellation continue to evolve to enhance the accuracy of noisy quantum computations [10].

Future directions for VQE development include the integration of machine learning methods for parameter initialization and optimization, transfer learning approaches that leverage solutions from similar molecular systems, and continued refinement of adaptive ansatz construction to balance expressibility and hardware feasibility [9]. As quantum hardware continues to advance with improved coherence times and gate fidelities, the practical application space for VQE in drug development and molecular design is expected to expand significantly, potentially enabling quantum advantage for specific classes of chemical problems in the coming years [10] [9].

The field of computational chemistry continuously seeks powerful methods to solve the electronic structure problem, a fundamental challenge in quantum chemistry and materials science. This problem is characterized by the exponential growth of the Hilbert space with the number of molecular orbitals, making exact solutions infeasible for classical algorithms as system size increases [2]. Quantum computers offer a promising alternative as they naturally operate within exponentially large Hilbert spaces and can, in principle, represent many-body quantum states more efficiently [2]. However, current quantum hardware, termed Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) devices, faces significant limitations including qubit constraints, quantum noise, and high error rates [12] [13].

To address these challenges, researchers have developed hybrid quantum-classical algorithms that leverage the complementary strengths of both computational paradigms. The Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) has emerged as a leading hybrid algorithm specifically designed to find the ground state energy of molecular Hamiltonians [14] [15]. This algorithm combines quantum resources for preparing and measuring quantum states with classical optimization techniques to minimize the energy expectation value [15]. The hybrid approach mitigates the limitations of NISQ devices by distributing the computational workload according to the strengths of each platform: quantum processors handle the exponentially hard task of representing quantum states, while classical computers perform the optimization procedure [13].

The VQE algorithm represents just one manifestation of the broader hybrid architecture paradigm. As quantum computing technology continues to evolve, these hybrid approaches enable researchers to tackle increasingly complex chemical systems that are beyond the reach of purely classical methods, while remaining compatible with current hardware constraints [12] [16]. This application note details the specific implementations, protocols, and applications of hybrid architectures in molecular simulations for drug development and materials science.

Theoretical Framework of VQE for Molecular Systems

Electronic Structure Hamiltonian

The foundation of quantum chemistry simulations lies in solving the electronic structure Hamiltonian, which represents the total energy of a molecular system based on its atomic coordinates and electronic configurations [12]. In a non-relativistic setting under the Born-Oppenheimer approximation, the electronic Hamiltonian can be expressed as:

[ \hat{H}{\text{elec}} = \sum{pq} hq^p \hat{f}p^\dagger \hat{f}q + \frac{1}{2} \sum{pqrs} v{rs}^{pq} \hat{f}p^\dagger \hat{f}q^\dagger \hat{f}s \hat{f}_r ]

where the indices (p, q, r, s) label spin-orbitals, and ({\hat{f}p^\dagger, \hat{f}q}) are fermionic creation and annihilation operators [2]. The scalars ({hq^p}) and ({v{rs}^{pq}}) represent the one-electron and two-electron integrals, respectively, which can be precomputed using classical Hartree-Fock methods [2].

For implementation on quantum hardware, this fermionic Hamiltonian must be transformed into a qubit representation using fermion-to-qubit mappings such as the Jordan-Wigner transformation [2]:

[ \hat{f}p^\dagger \mapsto \frac{1}{2} (Xp - iYp) \bigotimes{q

]

}>[ \hat{f}p \mapsto \frac{1}{2} (Xp + iYp) \bigotimes{q

]

}>where (X, Y, Z) are Pauli matrices, and the qubit indices correspond to spin-orbital indices [2]. This transformation yields a qubit Hamiltonian comprising a sum of Pauli strings:

[ \hat{H}Q = \sum{j=1}^{NH} gj \bigotimes{\mu=1}^{NQ} \sigma{j,\mu} = \sum{j=1}^{NH} gj \mathbb{P}j^{(NQ)} ]

where (gj) are scalar coefficients, (NQ) is the number of qubits, and (\mathbb{P}j^{(NQ)}) represents Pauli words [2].

Variational Principle and Algorithmic Structure

The VQE algorithm operates on the variational principle, which states that the expectation value of the Hamiltonian with respect to any trial wavefunction is an upper bound to the true ground state energy [15]:

[ E_0 \leq \frac{\langle \psi(\theta) | \hat{H} | \psi(\theta) \rangle}{\langle \psi(\theta) | \psi(\theta) \rangle} ]

The algorithm minimizes this expectation value through an iterative process [15]:

Ansatz Preparation: A parameterized quantum circuit (U(\theta)) prepares the trial wavefunction (|\psi(\theta)\rangle = U(\theta)|\psi0\rangle) from an initial state (|\psi0\rangle) (typically Hartree-Fock)

Quantum Circuit Execution: The quantum computer measures the expectation values of the Hamiltonian terms

Classical Optimization: A classical optimizer adjusts the parameters (\theta) to minimize the energy expectation value

Iteration and Convergence: Steps 2-3 repeat until energy convergence is achieved [15]

Table 1: Key Mathematical Components in VQE Formulation

| Component | Mathematical Representation | Role in VQE | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hamiltonian | (\hat{H} = \sumj gj \mathbb{P}_j) | Defines the physical system and its energy levels | ||

| Ansatz | ( | \psi(\theta)\rangle = U(\theta) | \psi_0\rangle) | Parameterized trial wavefunction for energy optimization |

| Cost Function | (E(\theta) = \langle \psi(\theta) | \hat{H} | \psi(\theta)\rangle) | Objective function minimized by classical optimizer |

| Parameter Update | (\theta^{(k+1)} = \theta^{(k)} - \eta \nabla E(\theta^{(k)})) | Classical optimization step (gradient-based) |

Advanced Hybrid Methods and Extensions

Fragment Molecular Orbital-Based VQE (FMO/VQE)

For large molecular systems, the Fragment Molecular Orbital (FMO) method enhances VQE scalability by dividing the system into smaller fragments [12]. The FMO/VQE approach combines this fragmentation strategy with quantum computations, significantly reducing qubit requirements while maintaining accuracy. In this method:

- The total system is divided into individual fragments

- Monomer and dimer calculations are performed with electrostatic embedding from other fragments

- The FMO-based restricted Hartree-Fock (FMO-RHF) calculation involves:

- Fragmentation of the whole system

- Monomer SCF calculations in external electrostatic potential

- Dimer SCF calculations

- Total property evaluation [12]

This approach has demonstrated exceptional accuracy, achieving an absolute error of just 0.053 mHa with 8 qubits for a (\text{H}{24}) system using the STO-3G basis set, and an error of 1.376 mHa with 16 qubits for a (\text{H}{20}) system with the 6-31G basis set [12].

Quantum-Density Functional Theory (DFT) Embedding

Quantum-DFT embedding represents another powerful hybrid approach that integrates classical and quantum computing resources [13]. This method partitions the system into:

- A classical region where DFT handles less correlated electrons

- A quantum region where a quantum computer solves the strongly correlated part of the system [13]

The workflow consists of five main steps:

- Structure generation from databases (CCCBDB, JARVIS-DFT)

- Single-point calculations using PySCF to analyze molecular orbitals

- Active space selection using Active Space Transformer

- Quantum computation for the active space energy

- Result analysis and benchmarking against classical references [13]

This approach has been successfully applied to aluminum clusters (Al-, Al₂, and Al₃-), achieving percent errors consistently below 0.02% compared to CCCBDB benchmarks [13].

Qumode-Based VQE for Excited States

Recent advances have extended hybrid approaches to bosonic quantum devices using quantum harmonic oscillators (qumodes) instead of discrete qubits [2]. The Qumode Subspace VQE (QSS-VQE) leverages the Fock basis of bosonic qumodes in circuit quantum electrodynamics (cQED) devices to compute molecular excited states [2]. This approach offers:

- Access to large Hilbert spaces via Fock state representations

- Native gate operations that would require deep circuits on qubit-based architectures

- Efficient state preparation and reduced quantum resource requirements [2]

QSS-VQE operates within the subspace-search VQE framework, using a shared parameterized circuit applied to an orthonormal set of input states, naturally realized as Fock states on qumode platforms [2].

Figure 1: Workflow of the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) algorithm, illustrating the hybrid quantum-classical architecture. The classical computer handles Hamiltonian generation, energy calculation, and parameter optimization, while the quantum computer prepares ansatz states and performs quantum measurements.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard VQE Protocol for Molecular Ground States

Objective: Compute the ground state energy of a target molecule using the VQE algorithm.

Pre-requisites:

- Molecular geometry (atomic coordinates and bond lengths)

- Basis set selection (e.g., STO-3G, 6-31G)

- Qubit mapping strategy (e.g., Jordan-Wigner, Parity)

Procedure:

Molecular Hamiltonian Generation

- Define molecular geometry using atomic coordinates

- For Hâ‚‚ molecule: place atoms at (0, 0, 0) and (1.623 Ã…, 0, 0) for bond length 1.623 Ã… [15]

- Set molecular charge and multiplicity (0 and 1 for neutral singlet Hâ‚‚) [15]

- Use PySCF driver to compute molecular integrals and electronic structure properties [15]

Qubit Hamiltonian Transformation

Ansatz Selection and Initialization

Optimizer Configuration

Quantum Execution and Classical Optimization Loop

- Quantum computer: Prepare (|\psi(\theta)\rangle) and measure expectation values (\langle \mathbb{P}_j \rangle)

- Classical computer: Compute total energy (E(\theta) = \sumj gj \langle \mathbb{P}_j \rangle)

- Update parameters (\theta) using classical optimizer

- Repeat until convergence ((|E^{(k+1)} - E^{(k)}| < \text{tolerance}))

Result Validation

Table 2: Performance Comparison of VQE Implementation Strategies

| Method | System | Qubit Count | Accuracy | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard VQE | Hâ‚‚, LiH, BeHâ‚‚ | 4-10 | ~99.9% | Well-established, suitable for small molecules [17] |

| FMO/VQE | Hâ‚‚â‚„ (STO-3G) | 8 | 0.053 mHa error | Scalability to larger systems [12] |

| Quantum-DFT Embedding | Al clusters | Varies | <0.02% error | Handles strongly correlated electrons [13] |

| QSS-VQE | Dihydrogen, Cytosine | Varies | Comparable/qubit-based | Access to excited states [2] |

High-Precision Measurement Protocol

For applications requiring chemical precision (1.6 × 10â»Â³ Hartree), implement advanced measurement techniques [18]:

Locally Biased Random Measurements

- Select measurement settings with bigger impact on energy estimation

- Reduce shot overhead while maintaining informational completeness

Repeated Settings with Parallel Quantum Detector Tomography (QDT)

- Perform blended QDT alongside Hamiltonian measurements

- Mitigate readout errors by characterizing quantum detector

Blended Scheduling

- Execute multiple Hamiltonian-circuit pairs alongside QDT circuits

- Mitigate time-dependent noise through temporal averaging

This protocol has demonstrated reduction of measurement errors from 1-5% to 0.16% on IBM Eagle r3 hardware for BODIPY molecule energy estimation [18].

Figure 2: Quantum-DFT embedding workflow for complex molecular systems. The system is partitioned into classical and quantum regions, with DFT handling the bulk electrons and VQE solving the strongly correlated active space.

Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Hybrid Quantum-Classical Experiments

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| PySCF | Classical Computational Package | Molecular integral computation, Hartree-Fock calculations | Generate molecular orbitals, compute one- and two-electron integrals [13] [15] |

| Qiskit Nature | Quantum Computing Framework | Fermion-to-qubit mapping, ansatz construction, VQE implementation | Transform molecular Hamiltonians, build quantum circuits [13] |

| UCCSD Ansatz | Quantum Circuit Template | Chemistry-inspired parameterized wavefunction | Accurate ground state preparation for molecular systems [12] [15] |

| EfficientSU2 Ansatz | Quantum Circuit Template | Hardware-efficient parameterized wavefunction | NISQ-friendly circuit implementation [13] [15] |

| Parity Mapper | Encoding Tool | Fermion-to-qubit transformation | Reduce qubit requirements for molecular simulations [17] [15] |

| Quantum Detector Tomography | Error Mitigation Protocol | Readout error characterization and mitigation | High-precision measurements for chemical accuracy [18] |

| CCCBDB | Reference Database | Experimental and computational benchmark data | Validate quantum computation results [13] |

| JARVIS-DFT | Materials Database | Pre-optimized structures and properties | Source molecular geometries for simulations [13] |

Applications in Drug Development and Materials Science

Hybrid quantum-classical methods are demonstrating practical utility across pharmaceutical and materials science domains:

Drug Discovery Applications

Quantum-informed approaches are advancing drug discovery by enabling more accurate molecular simulations:

- Peptide Drug Discovery: QUELO v2.3 platform uses quantum mechanics to optimize peptide drug molecules, addressing limitations of classical mechanics in describing various peptide constructs [16]

- Molecular Stability and Binding Interactions: Hybrid approaches successfully predict molecular stability, binding interactions, and potential toxicity of collagen fragments used in dermal fillers, with computational predictions closely matching laboratory results [16]

- RNA Conformation Analysis: Quantum approaches identify 3D conformations of RNA molecules, exploring multiple folding pathways simultaneously to identify stable structures more efficiently than traditional methods [16]

- Covalent Inhibitor Design: Quantum computing has been applied to model covalent inhibitors targeting the cancer-associated KRAS G12C mutation, providing more accurate predictions of molecular behavior and reaction pathways [16]

Materials Science Applications

The benchmarking of VQE for aluminum clusters (Al-, Al₂, Al₃-) demonstrates the method's applicability to materials science problems [13]. These clusters represent intermediate complexity systems with relevance to catalysis and other materials applications [13]. The successful implementation of VQE with quantum-DFT embedding for these systems establishes a pathway for studying more complex materials with strongly correlated electrons.

Future Outlook

As quantum hardware continues to advance, hybrid approaches are expected to tackle increasingly complex problems:

- Larger Molecular Systems: Methods like FMO/VQE will enable simulations of larger biological molecules relevant to drug discovery [12]

- Dynamics and Reactions: Quantum-informed approaches may simulate reactive molecular dynamics, capturing bond formation/breaking and proton transfer [16]

- Whole Biological Systems: Eventually, predictive modeling of entire biological systems from metabolism to disease progression may become feasible [16]

The integration of quantum mechanics, classical computing, and artificial intelligence represents a powerful paradigm shift in computational chemistry and drug discovery, with hybrid architectures serving as the crucial bridge between current capabilities and future potential [16].

The Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) is a leading hybrid quantum-classical algorithm designed to find the ground state energy of molecular systems, making it a cornerstone for quantum chemistry simulations on Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) devices [19] [12]. By combining quantum state preparation with classical optimization, VQE provides a practical pathway to study molecular properties critical for fields like drug discovery [20] [21]. The algorithm's performance hinges on three interdependent components: the ansatz, which generates the trial wavefunction; the Hamiltonian, encoding the system's physical properties; and the optimization loop, which minimizes the energy expectation value [19]. This document details the protocols for implementing these components within molecular ground state research, providing application notes for scientists and drug development professionals.

The Hamiltonian: Formulating the Molecular Problem

The Hamiltonian operator (( \hat{H} )) is the fundamental descriptor of a quantum system's energy. In the context of molecular ground states, the electronic structure Hamiltonian is derived under the Born-Oppenheimer approximation, which assumes fixed nuclear positions [12]. The goal of VQE is to find the molecular ground state by minimizing the expectation value of this Hamiltonian [19].

Formulation and Qubit Mapping

The second-quantized molecular Hamiltonian is expressed as: [ \hat{H} = \sum{pq} h{pq} cp^\dagger cq + \frac{1}{2} \sum{pqrs} h{pqrs} cp^\dagger cq^\dagger cr cs ] where ( h{pq} ) and ( h{pqrs} ) are one- and two-electron integrals, and ( cp^\dagger ) and ( cp ) are fermionic creation and annihilation operators [12]. To execute computations on a quantum processor, this fermionic Hamiltonian must be mapped to a qubit Hamiltonian composed of Pauli operators (( X, Y, Z )) [19]. This is achieved through transformations such as the Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev transformations, resulting in a Hamiltonian of the form: [ \hat{H} = \sumi \alphai \hat{P}i ] where ( \alphai ) are real coefficients and ( \hat{P}_i ) are Pauli strings (tensor products of Pauli operators) [19].

Application Note: Hamiltonian Preparation for Drug Discovery

In real-world drug discovery applications, such as simulating the covalent inhibition of the KRAS protein (a common cancer target), the size of the Hamiltonian can be prohibitive [20]. A common strategy to reduce qubit requirements is the active space approximation, which focuses the computation on a subset of chemically relevant molecular orbitals and electrons [20]. For instance, simulating a two-electron/two-orbital active space reduces the problem to a 2-qubit Hamiltonian, making it feasible for current NISQ devices while retaining accuracy crucial for predicting drug-target interactions [20].

Table: Common Qubit Mapping Techniques for Molecular Hamiltonians

| Mapping Technique | Key Principle | Qubit Requirement | Typical Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jordan-Wigner [19] | Encodes occupation number in a binary string; uses long Pauli strings to enforce anti-symmetry. | ( N ) qubits for ( N ) spin-orbitals | Fundamental simulations; easily understood mappings. |

| Bravyi-Kitaev [19] | Uses a more efficient binary mapping that reduces the Pauli string length. | ( N ) qubits for ( N ) spin-orbitals | Preferred for its efficiency in reducing circuit complexity. |

| Parity Transformation [20] | Encodes parity information (sum modulo 2 of occupation numbers). | ( N ) qubits for ( N ) spin-orbitals | Can simplify certain quantum circuit operations. |

The Ansatz: Designing the Trial Wavefunction

The ansatz is a parameterized quantum circuit ( U(\vec{\theta}) ) responsible for preparing a trial wavefunction ( |\psi(\vec{\theta})\rangle ) that approximates the true molecular ground state [19]. The choice of ansatz is critical as it dictates the expressivity of the wavefunction, the trainability of the parameters, and the hardware efficiency of the circuit.

Ansatz Paradigms

Two predominant paradigms exist for ansatz design: physically-inspired and hardware-efficient ansätze.

- Physically-Inspired Ansätze: These are derived from principles of quantum chemistry. The Unitary Coupled Cluster (UCC) ansatz, particularly UCC with Single and Double excitations (UCCSD), is a popular choice [12] [20]. It is inspired by the classical coupled-cluster method and provides high accuracy for molecular systems, though it can lead to deep quantum circuits [12].

- Hardware-Efficient Ansätze (HEA): These ansätze prioritize the native gate set and connectivity of a specific quantum processor [19]. They typically consist of alternating layers of single-qubit rotational gates and entangling two-qubit gates. While they are shallower and more noise-resilient, they may be more prone to barren plateaus and may not always preserve physical symmetries [19].

Advanced Ansatz Strategies: Adaptive and Distributed Design

To overcome the limitations of fixed ansätze, advanced strategies have been developed:

- Adaptive VQE (ADAPT-VQE): This algorithm constructs the ansatz iteratively by selecting operators from a predefined pool (e.g., fermionic excitations) based on a gradient criterion, which helps in building compact and problem-tailored circuits [10]. A gradient-free variant, Greedy Gradient-free Adaptive VQE (GGA-VQE), has also been introduced to improve resilience to statistical noise on real hardware [10].

- Slice-Wise Initial State Optimization: This method bridges adaptive and physics-inspired approaches. A pre-defined ansatz (e.g., the Hamiltonian Variational Ansatz) is broken into "slices," and their parameters are optimized sequentially. This subspace optimization provides a better initial state for the full circuit, improving convergence and reducing the number of function evaluations [22].

- Distributed Ansätze (DVQE): For large systems, the ansatz can be distributed across multiple logical quantum processing units (QPUs). Distributed ansatz circuits are constructed to preserve the fidelity of the full state vector, enabling the consistent estimation of energies while overcoming individual hardware limitations on qubit count and circuit depth [23].

Table: Comparison of Ansatz Types for Molecular Simulations

| Ansatz Type | Key Feature | Advantage | Challenge |

|---|---|---|---|

| UCCSD [12] [20] | Chemistry-inspired; based on fermionic excitation operators. | High accuracy; systematically improvable. | Circuit depth can be large; harder to run on NISQ devices. |

| Hardware-Efficient [19] [20] | Uses native device gates; low-depth. | More resilient to noise on specific hardware. | Can suffer from barren plateaus; less chemically aware. |

| Adaptive (e.g., ADAPT) [10] | Builds circuit iteratively from an operator pool. | Compact, system-tailored circuits; avoids redundant operators. | High measurement overhead for operator selection. |

Diagram: Ansatz Selection and Preparation Workflow

The Optimization Loop: A Classical-Quantum Hybrid

The optimization loop is the classical component that variationally adjusts the ansatz parameters ( \vec{\theta} ) to minimize the expectation value of the energy: [ E(\vec{\theta}) = \langle \psi(\vec{\theta}) | \hat{H} | \psi(\vec{\theta}) \rangle. ] This is achieved by iteratively evaluating the energy on the quantum computer and using a classical optimizer to update the parameters [19].

Core Optimization Protocol

The standard VQE optimization loop follows these steps:

- Initial State Preparation: Initialize the quantum processor to a reference state, often the Hartree-Fock state, which is a mean-field approximation of the molecular ground state [19] [12].

- Ansatz Execution: Apply the parameterized quantum circuit ( U(\vec{\theta}) ) to the initial state to generate the trial wavefunction ( |\psi(\vec{\theta})\rangle ).

- Energy Estimation: Measure the expectation value of the Hamiltonian ( \hat{H} = \sumi \alphai \hat{P}i ). This involves measuring each Pauli term ( \hat{P}i ) multiple times ("shots") to gather sufficient statistics [19].

- Classical Optimization: The computed energy ( E(\vec{\theta}) ) is fed to a classical optimizer, which calculates a new set of parameters ( \vec{\theta}_{\text{new}} ).

- Iteration: Steps 2-4 are repeated until the energy converges to a minimum, subject to a predefined convergence criterion.

Optimizers and Advanced Techniques

The choice of classical optimizer significantly impacts convergence. Gradient-based methods (e.g., L-BFGS-B) and gradient-free methods (e.g., COBYLA, Nelder-Mead, SPSA) are commonly used [23] [10]. The parameter-shift rule is a key technique for computing exact gradients on quantum hardware [19].

To enhance performance, several advanced techniques are employed:

- Metaheuristic Initialization: Instead of random initialization, strategies like using the ADAM optimizer in combination with metaheuristic initialization can improve convergence and robustness [23].

- Error Mitigation: Readout error mitigation and other techniques are applied to counteract the effects of noise on real hardware, leading to more accurate energy estimates [20].

- Fragment Molecular Orbital (FMO) Method: For large molecular systems like hydrogen clusters (( \text{H}_{24} )), the FMO method can be integrated with VQE. The system is divided into smaller fragments, and VQE is run on each fragment, dramatically reducing the required qubit count while maintaining accuracy [12].

Diagram: The VQE Optimization Loop

Integrated Protocols for Molecular Ground State Research

This section provides a detailed, step-by-step protocol for applying VQE to a molecular system, integrating the components discussed above.

Protocol: FMO/VQE for Large Molecular Systems

Objective: To compute the ground state energy of a large molecular system (e.g., a hydrogen cluster ( \text{H}_{24} )) using the Fragment Molecular Orbital (FMO) method combined with VQE [12].

Workflow:

Fragmentation:

- Divide the total molecular system into ( N ) smaller fragments (e.g., each ( \text{H}_2 ) molecule as a fragment).

- Note: The fragmentation scheme is a critical user-defined input.

Monomer SCF Calculation:

- For each fragment (monomer ( I )), perform a restricted Hartree-Fock (RHF) calculation in the electrostatic potential generated by all other ( N-1 ) fragments.

- The Hamiltonian for monomer ( I ) is: ( \hat{H}I \PsiI = EI \PsiI ).

- This step is performed classically to obtain the monomer wavefunctions and densities.

Dimer SCF Calculation:

- For pairs of fragments (dimers ( IJ )), perform an RHF calculation in the electrostatic potential of the remaining system.

- This captures the inter-fragment correlation energy.

Total Energy Evaluation:

- The total FMO energy ( E_\text{FMO} ) is computed classically as a sum of monomer and dimer contributions with a correction to avoid double-counting.

VQE on Fragments:

- For each fragment (monomer or dimer), map its electronic structure problem to a qubit Hamiltonian using, for example, the Jordan-Wigner transformation.

- Select an ansatz (e.g., UCCSD) and execute the standard VQE optimization loop to find the fragment's ground state energy.

- Critical Step: The FMO method provides an effective, pre-computed initial state for the VQE optimization on each fragment, improving convergence.

Result Aggregation:

- The final energy of the total system is a composite of the VQE-computed energies from the individual fragments.

Validation: In a study on ( \text{H}_{24} ) with the STO-3G basis set, the FMO/VQE method achieved an absolute error of only 0.053 milliHartree compared to the full system calculation, while using only 8 qubits per fragment calculation instead of the 48 qubits a monolithic approach would require [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table: Key Computational "Reagents" for VQE in Molecular Research

| Item / Resource | Function / Purpose | Example Instances |

|---|---|---|

| Electronic Structure Package | Computes molecular integrals (( h{pq}, h{pqrs} )) for Hamiltonian construction. | PySCF, Psi4, Gaussian |

| Quantum Computing Framework | Provides tools for mapping, ansatz design, circuit execution, and measurement. | Qiskit (with Nature), TenCirChem [20], raiselab/DVQE [23] |

| Classical Optimizer | Variationally updates ansatz parameters to minimize energy. | COBYLA, L-BFGS-B, ADAM [23], SPSA |

| Operator Pool (For Adaptive VQE) | Library of unitary operators from which the adaptive ansatz is constructed. | Fermionic excitation operators (e.g., ( ap^\dagger aq ), ( ap^\dagger aq^\dagger ar as )) [10] |

| Error Mitigation Module | Applies techniques to reduce the effect of quantum hardware noise on results. | Readout error mitigation, zero-noise extrapolation [20] |

| 3-Bromo-2-hydroxypropanoic acid | 3-Bromo-2-hydroxypropanoic acid, CAS:32777-03-0, MF:C3H5BrO3, MW:168.97 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 2-Isopropyl-6-methylphenyl isothiocyanate | 2-Isopropyl-6-methylphenyl isothiocyanate, CAS:306935-86-4, MF:C11H13NS, MW:191.29 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) has emerged as a leading algorithm for finding molecular ground-state energies on Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) hardware. This hybrid quantum-classical algorithm is particularly suited to current quantum devices, which typically feature 50-1000 qubits with error rates that limit circuit depth to approximately 1,000 operations before noise overwhelms the computational signal [24]. The fundamental operating principle of VQE relies on the Rayleigh-Ritz variational principle, which establishes that for any parameterized trial wavefunction ( |ψ(θ)\rangle ), the expectation value of the Hamiltonian ( \langle ψ(θ)|H|ψ(θ)\rangle ) provides an upper bound to the true ground-state energy ( E_0 ) [25]. This makes VQE inherently resilient to certain noise types, as the algorithm naturally converges toward this lower bound even in the presence of imperfections.

For researchers in pharmaceutical development and materials science, VQE offers a pathway to quantum-accelerated discovery by enabling more accurate simulation of molecular systems than classical methods can efficiently provide. Demonstrations have already achieved chemical accuracy (<1.6 mHa) for small molecules like H₂, LiH, and BeH₂ using hardware-efficient ansätze on superconducting qubits [25]. The algorithm's hybrid nature delegates the computationally expensive task of energy expectation estimation to the quantum processor while leveraging classical optimization to navigate the parameter landscape, creating a pragmatic division of labor that respects current technological constraints.

Quantum Hardware Landscape and Noise Challenges

Current Quantum Hardware Specifications

The performance of VQE is intrinsically linked to the hardware specifications of available quantum processors. Current NISQ devices from leading providers exhibit characteristic limitations that directly impact algorithm design and implementation.

Table: Representative NISQ Hardware Capabilities for VQE Implementation

| Hardware Platform | Qubit Count | Gate Fidelities | Coherence Times | Key Limitations for VQE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Superconducting (e.g., IBM) | 5-127+ qubits | 99.5% (1-qubit), 95-99% (2-qubit) [25] | ~100 μs [25] | Limited connectivity, decoherence during deep circuits |

| Trapped Ion (e.g., Quantinuum) | 36-56 qubits [26] [27] | >99.9% (2-qubit gates) [28] | ~0.6 ms (best-performing qubits) [26] | Slower gate speeds (~10 μs) [27] |

| Neutral Atom (e.g., QuEra) | 100+ qubits | N/A (information not provided in search results) | N/A (information not provided in search results | Measurement fidelity ~98% [27] |

Taxonomy of Quantum Errors in VQE

The execution of VQE on NISQ hardware is compromised by several interrelated noise sources that corrupt quantum information throughout the computation:

Decoherence: The fragile quantum state of qubits deteriorates due to environmental interactions, with characteristic relaxation (Tâ‚) and dephasing (Tâ‚‚) times imposing strict limits on algorithm duration [24]. This represents a fundamental physical constraint requiring VQE circuits to be "shallow" with minimal depth.

Gate Errors: Each quantum operation introduces inaccuracies, with two-qubit entangling gates (essential for chemistry applications) typically exhibiting higher error rates than single-qubit gates [29]. These infidelities accumulate exponentially throughout the circuit execution.

Measurement Errors: The final quantum state readout may misreport |0⟩ as |1⟩ or vice versa, introducing systematic bias in energy expectation measurements [30]. This noise source particularly impacts the Hamiltonian term estimation crucial to VQE.

State Preparation Errors: Initialization of the starting quantum state introduces inaccuracies that propagate through the entire circuit, affecting the initial parameter optimization landscape [29].

Error Mitigation Strategies for VQE

Readout Error Mitigation

Measurement error mitigation addresses the misclassification of qubit states during readout, a significant source of systematic error in VQE energy calculations. The technique employs calibration experiments to characterize the confusion matrix of the detection system:

Protocol: Measurement Error Mitigation for VQE

- Prepare each computational basis state (|0...0⟩, |0...1⟩, ..., |1...1⟩) on the quantum processor

- Perform immediate measurement and repeat to construct a response matrix M, where Mᵢⱼ = probability of measuring state i when preparing state j

- During VQE execution, apply the inverse response matrix Mâ»Â¹ to the measured probability distributions

- Use the corrected probabilities for Hamiltonian expectation value calculation

This approach has demonstrated significant improvements, with one study showing an older 5-qubit processor (IBMQ Belem) equipped with optimized Twirled Readout Error Extinction (T-REx) achieving ground-state energy estimations an order of magnitude more accurate than those from a more advanced 156-qubit device without error mitigation [31].

Zero-Noise Extrapolation (ZNE)

Zero-Noise Extrapolation strategically amplifies circuit noise to enable extrapolation back to the zero-noise condition, providing a powerful technique for mitigating gate-level errors without quantum overhead:

Protocol: ZNE for VQE Energy Estimation

- Execute the VQE ansatz circuit at multiple intentionally heightened noise levels (e.g., 1×, 2×, 3× base noise)

- Noise amplification can be achieved through unitary folding (replacing U → U U†U) or pulse stretching [30]

- Measure the energy expectation value ⟨H(λ)⟩ at each noise scale factor λ

- Fit the observed trend to a phenomenological model (e.g., linear, exponential, or Richardson extrapolation)

- Extrapolate to λ = 0 to estimate the noise-free energy value

ZNE has proven particularly effective for VQE as it doesn't require detailed noise characterization and can be implemented as a post-processing technique [30] [27].

Probabilistic Error Cancellation

Probabilistic Error Cancellation represents a more advanced technique that employs a quasi-probability decomposition to effectively simulate inverse noise channels:

Protocol: PEC Implementation for VQE

- Characterize the native gate set to construct a comprehensive noise model for the target device

- Decompose the ideal quantum channel for each gate into a linear combination of implementable noisy operations

- During VQE execution, randomly sample from these noisy operations according to the quasi-probability distribution

- Collect measurement outcomes over many shots, weighting results by appropriate coefficients

- Compute the final expectation value from the weighted average, which cancels systematic noise contributions

While PEC can provide more accurate error suppression than ZNE, it requires substantially more circuit executions (shots) to achieve statistical significance, increasing computational cost [30].

Comparative Performance of Error Mitigation Techniques

Table: Error Mitigation Methods for VQE Applications

| Technique | Theoretical Basis | Quantum Overhead | Classical Overhead | Reported Efficacy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measurement Error Mitigation | Response matrix inversion | Minimal (additional calibration circuits) | Low (matrix inversion) | Enables order-of-magnitude accuracy improvements [31] |

| Zero-Noise Extrapolation (ZNE) | Noise scaling and extrapolation | Moderate (2-4× circuit executions) | Low (curve fitting) | Essential for meaningful energy estimates on NISQ devices [30] |

| Probabilistic Error Cancellation (PEC) | Quasi-probability decomposition | High (10-100× sampling overhead) | High (noise tomography) | Near-exact error removal but resource-intensive [30] |

| Symmetry Verification | Subspace projection based on conserved quantities | Moderate (additional measurements) | Low (post-selection) | Effectively suppresses errors violating physical constraints [30] |

Experimental Protocol: VQE for Molecular Ground States

Problem Formulation and Qubit Mapping

The electronic structure Hamiltonian for a molecular system in second quantized form is:

[ H{el}=\sum{p,q}h{pq}a^{\dagger}{p}a{q}+\sum{p,q,r,s}h{pqrs}a^{\dagger}{p}a^{\dagger}{q}a{r}a_{s} ]

where ( h{pq} ) and ( h{pqrs} ) are one- and two-electron integrals, and ( a^{\dagger}{p}/a{p} ) are fermionic creation/annihilation operators [31].

Protocol: Hamiltonian Preparation

- Select molecular coordinates and basis set (e.g., STO-3G, 6-31G) for the target system

- Compute one- and two-electron integrals using classical electronic structure software

- Apply active space approximation (e.g., freezing core orbitals) to reduce qubit requirements

- Transform fermionic operators to qubit operators using Jordan-Wigner, Bravyi-Kitaev, or parity mapping

- Apply qubit tapering to reduce Hamiltonian complexity by exploiting symmetries [31]

For example, in a BeHâ‚‚ study using 3 active orbitals, parity mapping with qubit tapering reduced qubit requirements from 6 to 4, enabling execution on a 5-qubit quantum processor [31].

Ansatz Selection and Parameter Optimization

The choice of parameterized quantum circuit (ansatz) represents a critical balance between expressibility and noise resilience:

Protocol: Ansatz Configuration for Noisy Hardware

- Hardware-Efficient Ansatz: Design circuits respecting native device connectivity and gate sets, minimizing SWAP overhead [31]

- Physically-Inspired Ansatz: Implement unitary coupled cluster (UCCSD) variants for chemically meaningful parameters, despite increased depth [25]

- Layer-wise Construction: Build circuits iteratively, balancing expressiveness against noise accumulation

- Parameter Initialization: Employ classical heuristics (e.g., MP2 coefficients for UCC) or meta-learning approaches to initialize near solutions

For optimization, the Simultaneous Perturbation Stochastic Approximation (SPSA) algorithm has demonstrated relatively good convergence under noise conditions due to its inherent noise resilience and minimal measurement requirements [31] [25].

Diagram Title: VQE Experimental Workflow with Error Mitigation

Integrated Error Mitigation Protocol

A robust VQE implementation employs multiple error mitigation strategies in concert:

Protocol: Comprehensive Error Mitigation for VQE

- Pre-calibration Phase:

- Characterize readout error matrix for measurement mitigation

- Profile gate fidelities and coherence times for noise model construction

- Determine optimal noise scaling factors for ZNE

Execution Phase:

- Apply dynamical decoupling sequences during idle periods

- Implement symmetry verification for physics-based error detection

- Execute circuits at multiple noise scales for ZNE

Post-processing Phase:

- Apply measurement error mitigation to raw results

- Perform zero-noise extrapolation on calibrated measurements

- Use error-aware optimizers (e.g., SPSA) resilient to stochastic noise

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table: Critical Resources for VQE Experiments on NISQ Hardware

| Resource Category | Specific Solution | Function in VQE Pipeline |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Software Frameworks | Qiskit (IBM), PennyLane (Xanadu), CUDA-Q (NVIDIA) [29] [32] | Circuit construction, execution management, and hybrid optimization |

| Error Mitigation Libraries | Mitiq, T-REx, Qiskit Ignis [31] [30] | Implementation of ZNE, PEC, and measurement error mitigation |

| Classical Computational Tools | InQuanto (Quantinuum), NVIDIA Grace Blackwell platform [32] | Hamiltonian preparation, integral computation, and classical co-processing |

| Quantum Hardware Access | IBM Quantum Systems, Quantinuum H-series, Amazon Braket [26] [32] | Physical execution of parameterized quantum circuits |

| Electronic Structure Packages | PySCF, QChem, Gaussian with quantum interfaces | Molecular integral computation and active space selection |

| ethyl 4-oxo-4-(4-n-propoxyphenyl)butyrate | ethyl 4-oxo-4-(4-n-propoxyphenyl)butyrate, CAS:39496-81-6, MF:C15H20O4, MW:264.32 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Cyclobutyl 4-thiomethylphenyl ketone | Cyclobutyl 4-thiomethylphenyl ketone, CAS:716341-27-4, MF:C12H14OS, MW:206.31 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Future Outlook and Emerging Solutions

The quantum computing industry is rapidly evolving from the NISQ era toward fault-tolerant capabilities, with quantum error correction (QEC) transitioning from theoretical concept to engineering priority [28]. Recent breakthroughs include Google's demonstration of exponential error reduction as qubit counts increase and Quantinuum's development of concatenated symplectic double codes that facilitate easier logical computation [26] [32]. These advances are particularly relevant for VQE applications, as they promise to overcome the coherence limitations that currently restrict circuit depth and accuracy.

The emerging paradigm of quantum-centric supercomputing integrates quantum processors with classical high-performance computing infrastructure, addressing the latency challenges in hybrid algorithms [26] [32]. For pharmaceutical researchers, this progression suggests a strategic pathway where current VQE implementations with error mitigation will naturally evolve toward more accurate simulation of larger molecular systems, potentially transforming early-stage drug discovery within the coming decade.

Implementing VQE: From Circuit Design to Pharmaceutical Application

The ansatz, a parameterized quantum circuit, is the cornerstone of the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) algorithm. Its construction dictates the algorithm's ability to accurately prepare the ground state of a molecular system while remaining executable on near-term, noisy hardware [9]. The fundamental challenge lies in balancing expressibility—the capacity to represent the true ground state—with hardware feasibility, which limits circuit depth and complexity [33]. This document details the two primary philosophical approaches to this challenge: physically-inspired and hardware-efficient ansatz design, providing application notes and protocols for researchers in quantum chemistry and drug development.

Ansatz Typology and Comparative Analysis

The choice of ansatz is a critical determinant of VQE performance, influencing convergence, accuracy, and resource requirements [9]. The main classes of ansätze and their characteristics are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Comparison of Major Ansatz Types for Molecular Ground State VQE Simulations

| Ansatz Type | Key Features | Typical Applications | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physically-Inspired (e.g., UCCSD) [33] [9] | Based on fermionic excitation operators; derived from coupled cluster theory; physically motivated. | Quantum chemistry (Hâ‚‚, LiH, Hâ‚‚O); molecular ground state energy estimation [9]. | High circuit depth; poor scalability with system size; requires Trotterization [9]. |

| Hardware-Efficient [33] [9] | Constructed from native gate sets and qubit connectivity; low depth; tailored to specific device. | NISQ device demonstrations; ground state estimation for atoms (e.g., Silicon) [33]. | May break physical symmetries; prone to "barren plateaus" in optimization [9]. |

| k-UpCCGSD [33] [9] | Uses generalized singles and paired doubles; more compact than UCCSD; a variant of physically-inspired ansatz. | Quantum chemistry for larger molecules; offers a trade-off between accuracy and circuit complexity [33]. | Less established performance across diverse molecular sets; parameter optimization can be challenging. |

| Qubit-Coupled Cluster [33] | A qubit-friendly structure that combines the accuracy of coupled cluster theory with the feasibility for variational quantum algorithms. | Designed for near-term devices as an alternative to UCCSD [33]. | Circuit depth can still be significant for complex molecules. |

| Evolutionary/Genetic [9] | Circuit topology and parameters are dynamically evolved using genetic algorithms and fitness functions. | Hardware-adaptive circuit discovery; achieves shallow circuits and superior noise resilience [9]. | High optimization overhead for the classical computer. |

Hardware-Efficient Ansatz Design and Protocols

Design Principles

Hardware-efficient ansätze (HEA) prioritize circuit executability on Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) devices. They are constructed from layers of parameterized single-qubit rotations and entangling two-qubit gates native to the target quantum processor, such as CNOT or CZ gates arranged in a specific topology (e.g., linear or ladder) [9]. This design minimizes gate count and circuit depth, which is crucial given limited coherence times [33].

Protocol: Implementing and Benchmarking a Hardware-Efficient Ansatz

This protocol outlines the steps for constructing and testing a hardware-efficient ansatz for a molecular system like the silicon atom [33].

Problem Formulation and Qubit Mapping:

- Input: Molecular geometry of the target system (e.g., Silicon atom).

- Procedure: Generate the electronic Hamiltonian in the second quantized form. Map the fermionic Hamiltonian to a qubit operator using the Jordan-Wigner or Bravyi-Kitaev transformation [9].

- Output: Qubit Hamiltonian

Hrepresented as a sum of Pauli strings.

Ansatz Construction:

- Architecture Selection: Choose a hardware-efficient ansatz architecture, such as

ParticleConservingU2, which has demonstrated robustness across various optimizers [33]. - Circuit Assembly: Construct the parameterized circuit

U(θ)using:- Single-qubit gates:

R_y(θ_i)andR_z(θ_j)gates for maximum expressibility of single-qubit states. - Entangling gates: A fixed pattern of CNOT gates that matches the hardware connectivity (e.g., a linear chain of alternating CNOTs between adjacent qubits).

- Layering: Repeat the block of single-qubit rotations and entangling gates for

Llayers to increase expressibility.

- Single-qubit gates:

- Architecture Selection: Choose a hardware-efficient ansatz architecture, such as

Parameter Initialization and Optimization:

- Initialization: Initialize all parameters

θto zero. Research has shown this can lead to faster and more stable convergence compared to random initialization [33]. - Classical Optimization: Use the ADAM optimizer, an adaptive moment estimation algorithm, which has proven effective for HEA [33]. The objective is to minimize the energy expectation value

E(θ) = <0| U†(θ) H U(θ) |0>. - Measurement: Estimate

E(θ)by measuring the quantum circuit in the Pauli bases of the Hamiltonian terms. Employ techniques like grouping commuting Pauli operators to reduce the number of required measurements.

- Initialization: Initialize all parameters

Benchmarking and Validation:

- Metric: Calculate the error in the ground state energy relative to the full configuration interaction (FCI) or experimental value.

- Comparison: Benchmark the performance (accuracy and convergence speed) against other ansätze, such as UCCSD, under simulated noise conditions to evaluate robustness [33].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the protocol for implementing a hardware-efficient ansatz.

Physically-Inspired Ansatz Design and Protocols

Design Principles

Physically-inspired ansätze, such as the Unitary Coupled Cluster (UCC) family, incorporate knowledge of the molecular system's structure. The UCCSD (Unitary Coupled Cluster with Singles and Doubles) ansatz is a prominent example, defined as U(θ) = exp(T(θ) - T†(θ)), where T(θ) is the cluster operator comprising single and double excitation terms from the reference Hartree-Fock state [9]. This approach ensures the ansatz explores a physically relevant subspace of the full Hilbert space.

Protocol: Implementing the UCCSD Ansatz

This protocol details the steps for a UCCSD-based VQE calculation, which has been shown to yield stable and precise results for molecules like SiHâ‚„ and Hâ‚‚O [9].

Reference State Preparation:

- Input: Molecular geometry and basis set.

- Procedure: Perform a classical Hartree-Fock (HF) calculation to obtain the reference wavefunction

|ψ_HF>. - Output: The HF state, which is prepared on the quantum computer as a computational basis state

|0110...>via a series of Pauli-X gates.